Praying Through Politics, Ruling Through Religion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of School Under South Tripura District

List of School under South Tripura District Sl No Block Name School Name School Management 1 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 2 BAGAFA NAGDA PARA S.B State Govt. Managed 3 BAGAFA WEST BAGAFA H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 4 BAGAFA UTTAR KANCHANNAGAR S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 5 BAGAFA SANTI COL. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 6 BAGAFA BAGAFA ASRAM H.S SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 7 BAGAFA KALACHARA HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 8 BAGAFA PADMA MOHAN R.P. S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 9 BAGAFA KHEMANANDATILLA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 10 BAGAFA KALA LOWGONG J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 11 BAGAFA ISLAMIA QURANIA MADRASSA SPQEM MADRASSA 12 BAGAFA ASRAM COL. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 13 BAGAFA RADHA KISHORE GANJ S.B. State Govt. Managed 14 BAGAFA KAMANI DAS PARA J.B. SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 15 BAGAFA ASWINI TRIPURA PARA J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 16 BAGAFA PURNAJOY R.P. J.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 17 BAGAFA GARDHANG S.B SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 18 BAGAFA PRATI PRASAD R.P. J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 19 BAGAFA PASCHIM KATHALIACHARA J.B. State Govt. Managed 20 BAGAFA RAJ PRASAD CHOW. MEMORIAL HIGH SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 21 BAGAFA ALLOYCHARRA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 22 BAGAFA GANGARAI PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 23 BAGAFA KIRI CHANDRA PARA J.B SCHOOL TTAADC Managed 24 BAGAFA TAUCHRAICHA CHOW PARA J.B TTAADC Managed 25 BAGAFA TWIKORMO HS SCHOOL State Govt. Managed 26 BAGAFA GANGARAI S.B SCHOOL State Govt. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Within Hinduism's Vast Collection of Mythology, the Landscape of India

History, Heritage, and Myth Item Type Article Authors Simmons, Caleb Citation History, Heritage, and Myth Simmons, Caleb, Worldviews: Global Religions, Culture, and Ecology, 22, 216-237 (2018), DOI:https:// doi.org/10.1163/15685357-02203101 DOI 10.1163/15685357-02203101 Publisher BRILL ACADEMIC PUBLISHERS Journal WORLDVIEWS-GLOBAL RELIGIONS CULTURE AND ECOLOGY Rights Copyright © 2018, Brill. Download date 30/09/2021 20:27:09 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final accepted manuscript Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/631038 1 History, Heritage, and Myth: Local Historical Imagination in the Fight to Preserve Chamundi Hill in Mysore City1 Abstract: This essay examines popular and public discourse surrounding the broad, amorphous, and largely grassroots campaign to "Save Chamundi Hill" in Mysore City. The focus of this study is in the develop of the language of "heritage" relating to the Hill starting in the mid-2000s that implicitly connected its heritage to the mythic events of the slaying of the buffalo-demon. This essay argues that the connection between the Hill and "heritage" grows from an assumption that the landscape is historically important because of its role in the myth of the goddess and the buffalo- demon, which is interwoven into the city's history. It demonstrates that this assumption is rooted within a local historical consciousness that places mythic events within the chronology of human history that arose as a negotiation of Indian and colonial understandings of historiography. Keywords: Hinduism; Goddess; India; Myth; History; Mysore; Chamundi Hills; Heritage 1. Introduction The landscape of India plays a crucial role for religious life in the subcontinent as its topography plays an integral part in the collective mythic imagination with cities, villages, mountains, rivers, and regions serving as the stage upon which mythic events of the epics and Purāṇas unfolded. -

A Note on Vālmīki's Poetical Technique to Build His Rāmāyaṇa on the Basis

International Journal of Sanskrit Research 2017; 3(2): 78-81 International Journal of Sanskrit Research2015; 1(3):07-12 ISSN: 2394-7519 A note on Vālmīki’s poetical technique to build his IJSR 2017; 3(2): 78-81 © 2017 IJSR Rāmāyaṇa on the basis of the Rāma- Stories of oral www.anantaajournal.com literature Received: 19-01-2017 Accepted: 20-02-2017 Priyanka Saha Priyanka Saha Research Scholar, Dept of Sanskrit Tripura University, An Abstract Tripura, India If an avid reader goes through between the lines of the text of Valmiki’s Ramayana, he obviously often encounters such a context from which it appears that a vast multitude of tales and legends mostly dealing with the rise and fall of Rama’s ancestors over many generations have been memorized. Key words: Introduction, Ramayana, writing method of Valmiki and manuscriptology If an avid reader goes through between the lines of the text of Valmiki’s Ramayana, he obviously often encounters such a context from which it appears that a vast multitude of tales and legends mostly dealing with the rise and fall of ’s ancestors over many Rama generations have been memorized. To warrant such an inclusion of these stories to the main corpus of the Ramayana, which ordinarily consists of the narratives of Rama’s later military adventures 1, it may, however, be said that about the innermost thoughts and feelings of the poet bent upon to sketch his literary art, one does not possess adequate knowledge other than the little that can, perhaps, be inferred from the poet’s method of selection of the subject- matter for his work. -

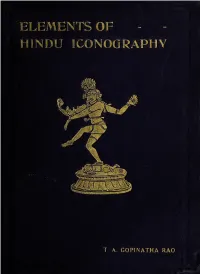

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

ELEMENTS of HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All Books Are Subject to Recall After Two Weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library

' ^'•' .'': mMMMMMM^M^-.:^':^' ;'''}',l.;0^l!v."';'.V:'i.\~':;' ' ASIA LIBRARY ANNEX 2 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY All books are subject to recall after two weeks Olin/Kroch Library DATE DUE Cornell University Library The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924071128841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 1924 071 28 841 ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A.^GOPINATHA RAO. M.A. SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part I. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 All Rights Reserved. KC- /\t^iS33 PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE, MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. DEDICATED WITH KIND PERMISSION To HIS HIGHNESS SIR RAMAVARMA. Sri Padmanabhadasa, Vanchipala, Kulasekhara Kiritapati, Manney Sultan Maharaja Raja Ramaraja Bahadur, Shatnsher Jang, G.C.S.I., G.C.I. E., MAHARAJA OF TRAVANCORE, Member of the Royal Asiatic Society, London, Fellow of the Geographical Society, London, Fellow of the Madras University, Officer de L' Instruction Publique. By HIS HIGHNESSS HUMBLE SERVANT THE AUTHOR. PEEFACE. In bringing out the Second Volume of the Elements of Hindu Iconography, the author earnestly trusts that it will meet with the same favourable reception that was uniformly accorded to the first volume both by savants and the Press, for which he begs to take this opportunity of ten- dering his heart-felt thanks. No pains have of course been spared to make the present publication as informing and interesting as is possible in the case of the abstruse subject of Iconography. -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: -

Aarsha Vani (Voice of Sanatana Dharma)

AArsha Vani (Voice of Sanatana Dharma) March 2016 Volume: 2 Issue: 02 “Sarvam Sivamayam Jagat” Upcoming Pravachanams “Brahma and Vishnu worshipped Siva who manifested Himself on Maha Sivaratri day as Date: Mar 6- 12, 2016 11AM & 6:30PM ‘Maha Linga’. They propagated this through Gods and sages for the ultimate benefit of Topic: Maha Bharatha Gaadhalu - mankind. Worship of Siva on Maha Sivaratri day Bodhalu grants the merit of worshipping Siva the entire year. Venue: Jute Dharmasala, Kurukshetram Worshipping Siva in the form of ‘Paarthiva Linga’ Contact: Chandrasekhar Gupta 9246530318 (Linga made with clay) is effective. ‘Linga’ is the 9391033782 unified form of Siva and Shakti – the cylindrical Date: Mar 14-16, 2016 6:30PM sphere represents Siva and the base (Yoni) represents Topic: Hindu Dharmam-Swarupam, Shakti. Worshipping Siva at Maha Pradosham i.e. Swabhavam, Prabhavam twilight time and ‘Lingodbhava kala’ i.e. at midnight Venue: Mahati Auditorium, Tirupati on Maha Sivaratri day is auspicious and bestows Contact: C Subrahmanyam 9440352995 many favors. One should worship Nandiswara before Date: Mar 19 –23, 2016 6:30PM worshipping Siva. Observing Maha Sivaratri following all or at least one of the following Topic: Sri Kamakshi Mahima - Sri Guru Siva Dharmas grants everything here and hereafter - Parampara 1. Abhishekam – ‘Abhishekaat Atma Suddhi:’. Performing abhishekam grants internal Venue: Sri Vivekananda Samskruta purity. At mundane level, those who perform abhishekam are blessed with opulence and Patasala, Kurnool. success. Doing abhishekam with milk, curd, cow ghee, honey and sugar is in vogue in Contact: Jogayya Sarma 7382106171 many parts of Bharat. Rudram (Namakam & Chamakam) is chanted while performing VS Prasad 9440293007 abhishekam. -

Ack-Catalouge.Pdf

Television Films | Publishing Distribution PRODUCT CATALOGUE 2012-2013 About ACK Media India's leading entertainment and education company for young audiences. Some of India's most-loved brands including Amar Chitra Katha, Tinkle, Karadi Tales and well-known proprietary characters like Suppandi and Shikari Shambu are part of ACK Media. We develop products for multiple platforms including print, home video, broadcast television, films, mobile and online services. ACK Media also owns IBH- India Book House,India’s most established books and magazines distribution company. ACK Media is headquartered in Mumbai, with a product development studio in Bengaluru and a subsidiary in Chennai. To know more please visit us at ack-media.com Amar Chitra Katha,the flagship brand was founded in 1967 and is a household name in India. This illustrated series comprises of the best stories from the great epics, mythology, history and folktales. It has more than 400 comics in 20 languages that have sold 90 million copies to date, making it a cultural phenomenon. India's largest selling children's magazine in English. Tinkle truly stands for 'Where Learning Meets Fun’ and with its unique set of endearing proprietary characters like Suppandi, Shikari Shambu, Tantri the Mantri and many more, it has enthralled readers for over three decades. Tinkle also has its own community called tinkleonline.com which has a registered userbase of 2 lakh plus children. Its an interactive platform that enables children to creatively express themselves An independent subsidiary of ACK Media, Karadi Tales is a pioneer in the market for multi-media Indian content with over 45 titles in children's audiobooks, over 25 titles in home video and 10 adult audio biographies. -

A Study of Religious Beliefs and the Festivals of the Tribal's of Tripura

Volume 4, Issue 5, May – 2019 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 A Study of Religious Beliefs and the Festivals of the Tribal’s of Tripura with Special Reference to – Tripuris Sujit Kumar Das Research Scholar, Department of Indian Comparative Literature Assam University, Silchar Abstract:- It is believed that, “Religion is commonly Hinduism is not a like to Christianity on religious point understood on a belief that mankind has in visible ground. controlling power with a related emotion and sense of morality. The common features and nature of religion Many of the tribes of Tripura come moor and belief of the Tribal Religion are some as in the case of moor under influence of Hindu way of life, and their any so called higher. It is true that in the field of the tribal cults were roughly assimilated to Hinduism by simplest beliefs and practices of Tribal communities, Brahmins who are said to brought by Royal house of the non-Tribal virtuous people are not different from Tripura. But animism, the primitive from of religion, is them. But yet, there are differences on pragmatic still traceable in tribal’s thinking and out-looks among grounds ‘Which are not logically valid’. At present it the Hindu & Buddhist tribes. Now a new trend has must be suffice to say that “in any treatment of Tribal been found among them in which respect for their own beliefs and practices, it would be useful to sued indigenous culture and their identity are the dominant personal prejudices, or at least keep judgment in facts. -

Tripura Legacy

Heritage of Tripura : A Gift from the Older Generations The heritage and culture of tripura are vast and vivid because of the large number of races residing in the state from the ancient period. Every community has its own set of customs and traditions which it passes on to its younger generation. However, some of our customs and traditions remain the same throughout the state of Tripura . The heritage of Tripura is a beautiful gift from the older generation that helped the residents of Tripura to build a harmonious society. Preservation of the It is the rich heritage of Tripura will certainly bring prosperity for the entire state of Tripura . Tripura is an ancient princely State and blessed with a beautiful heritage. The citizens of Tripura are fortunate to have the same and the future generations would be immensely benefitted to get to see and experience the same. The informations , in this page had been accumulated by Sri Jaydip Sengupta, Engineer (Computer),TTAADC from the widely available resources in the public domain . Any further input from any resourceful persons may kindly be routed to the E Mail: [email protected] and could be intimated in the Cell No. 9436128336 The gleaming white Ujjayanta Palace located in the capital city of Agartala evokes the age of Tripura Maharajas. The name Ujjayanta Palace was given by Nobel Laureate Rabindranath Tagore. It is a unique experience to witness living history and Royal splendour within the walls of Ujjayanta Palace. This Palace was built by Maharaja Radha kishore Manikya in 1901A.D; this Indo-Saracenic building is set in large Mughal-style gardens on a lake front.