Rethinking Diversity Ideologies: Critical Multiculturalism and Its Implications for Social Justice Issues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field

Queer Theory, Ethno/Musicology, and the Disorientation of the Field Steven Moon We spend significant time and space in our academic lives positioning ourselves: within the theory of the field, in regard to the institution, within networks of interlocutors, scholars, performers, and so on. We are likewise trained to critique those positions, to identify modes of power in their myriad manifestations, and to work towards more equitable methods and theory. That is, we constantly are subject to attempts of disciplinary orienta- tion, and constantly negotiate forms of re-orientation. Sara Ahmed reminds us that we might ask not only how we are oriented within our discipline, but also about 1) how the discipline itself is oriented, and 2) how orien- tation within sexuality shapes how our bodies extend into space (2006). This space—from disciplinary space, to performance space, to the space of fieldwork and the archive—is a boundless environment cut by the trails of the constant reorientation of those before us. But our options are more than the dichotomy between “be oriented” and “re-orient oneself.” In this essay, I examine the development of the ethno/musicologies’ (queer) theoretical borrowings from anthropology, sociology, and literary/cultural studies in order to historicize the contemporary queer moment both fields are expe- riencing and demonstrate the ways in which it might dis-orient the field. I trace the histories of this queer-ing trend by beginning with early concep- tualizations of the ethno/musicological projects, scientism, and quantita- tive methods. This is in relation to the anthropological method of ethno- cartography in order to understand the historical difficulties in creating a queer qualitative field, as opposed to those based in hermeneutics. -

Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union's

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union’s East Border Brie, Mircea and Horga, Ioan and Şipoş, Sorin University of Oradea, Romania 2011 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/44082/ MPRA Paper No. 44082, posted 31 Jan 2013 05:28 UTC ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER ETHNICITY, CONFESSION AND INTERCULTURAL DIALOGUE AT THE EUROPEAN UNION EASTERN BORDER Mircea BRIE Ioan HORGA Sorin ŞIPOŞ (Coordinators) Debrecen/Oradea 2011 This present volume contains the papers of the international conference Ethnicity, Confession and Intercultural Dialogue at the European Union‟s East Border, held in Oradea between 2nd-5th of June 2011, organized by Institute for Euroregional Studies Oradea-Debrecen, University of Oradea and Department of International Relations and European Studies, with the support of the European Commission and Bihor County Council. CONTENTS INTRODUCTORY STUDIES Mircea BRIE Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Dialogue in the European Border Space.......11 Ioan HORGA Ethnicity, Religion and Intercultural Education in the Curricula of European Studies .......19 MINORITY AND MAJORITY IN THE EASTERN EUROPEAN AREA Victoria BEVZIUC Electoral Systems and Minorities Representations in the Eastern European Area........31 Sergiu CORNEA, Valentina CORNEA Administrative Tools in the Protection and Promotion of the Rights of Ethnic Minorities .............................................................................................................47 -

BTS' A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker a Dissertation

BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2019 Reading Committee: Anis Bawarshi, Chair Nancy Bou Ayash Juan C. Guerra Program Authorized to Offer Degree: English ©Copyright 2019 Judy-Gail Baker University of Washington Abstract BTS’ A.R.M.Y. Web 2.0 Composing: Fangirl Translinguality As Parasocial, Motile Literacy Praxis Judy-Gail Baker Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Anis Bawarshi English As a transcultural K-Pop fandom, 아미 [A.R.M.Y.] perform out-of-school, Web 2.0 English[es] composing to cooperatively translate, exchange and broker content for parasocially relating to/with members of the supergroup 방탄소년단 [BTS] and to/with each other. Using critical linguistic ethnography, this study traces how 아미 microbloggers’ digital conversations embody Jenkins’ principles of participatory fandom and Wenger’s characteristics of communities of learning practice. By creating Wei’s multilingual translanguaging spaces, 아미 assemble interest-based collectives Pérez González calls translation adhocracies, who collaboratively access resources, produce content and distribute fan compositions within and beyond fandom members. In-school K-12 and secondary learning writing Composition and Literacy Studies’ theory, research and pedagogy imagine learners as underdeveloped novices undergoing socialization to existing “native” discourses and genres and acquiring through “expert” instruction competencies for formal academic and professional “lived” composing. Critical discourse analysis of 아미 texts documents diverse learners’ initiating, mediating, translating and remixing transmodal, plurilingual compositions with agency, scope and sophistication that challenge the fields’ structural assumptions and deficit framing of students. -

The Treatment of Ethnic Minority Groups in Vietnam: Hmongs and Montagnards1

19th July 2017 (COI up to 20 June 2017) Vietnam Query Response: The treatment of ethnic minority groups in Vietnam: Hmongs and Montagnards1 Explanatory Note Sources and databases consulted List of Acronyms Issues for research 1) Background information on ethnic minority groups in Vietnam 2) Freedom of Religion a) How does Decree 92 (Specific provisions and measures for the implementation of the Ordinance on Belief and Religion, 1 January 2013) affect the right to freedom of religion in practice? b) Latest information with regards to the November 2016 ‘Law on Belief and Religion’ c) What restrictions or limitations are imposed by the authorities on Hmongs’ and Montagnards’ right to practice their faith? i) Reports of forced conversion (from Protestantism to animism) ii) Treatment by the police for religious reasons, including harassment, intimidation, monitoring, arrest and imprisonment iii) Reports of obstructing religious ceremonies (e.g. in house churches) or damaging religious property 3) Confiscation of land of Hmongs and Montagnards a) Information on the practices related to legal expropriation and illegal confiscation of land in Vietnam, including in relation to industrial development projects in the geographical areas where Hmong/Montagnards are living 4) Freedom of Movement of Hmongs and Montagnards a) Are the legal provisions of Art 274 of the Penal Code (Illegally leaving or entering the country: illegally staying abroad or in Vietnam) and Art 91 of the Penal Code (Fleeing abroad or defecting to stay overseas with a view to -

Ethnic Origin and Disability Data Collection in Europe: Measuring Inequality – Combating Discrimination

POLICY REPORT Equality Data Initiative ETHNIC ORIGIN AND DISABILITY DATA COLLECTION IN EUROPE: MEASURING INEQUALITY – COMBATING DISCRIMINATION November 2014 Authors: Isabelle Chopin, Lilla Farkas, and Catharina Germaine, Migration Policy Group for Open Society Foundations Editors: Costanza Hermanin and Angelina Atanasova POLICY REPORT: ETHNIC ORIGIN AND DISABILITY DATA COLLECTION IN EUROPE Contents Glossary .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive summary ............................................................................................................................5 1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................11 1.1 Note on concepts: equality data, ethnic data, disability, race and ethnic origin .......11 1.2 Purpose of the research .................................................................................................. 15 1.3 Statement of the issue ..................................................................................................... 17 2. Antecedents: European-level research and legal framework............................................. 21 2.1 Legal and policy frameworks for equality data collection in Europe ......................... 21 2.2 Research identifying a need for reliable and adequate equality data ....................... 26 2.3 European law ................................................................................................................. -

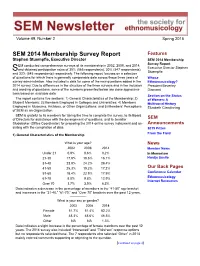

SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership

Volume 49, Number 2 Spring 2015 SEM 2014 Membership Survey Report Features Stephen Stuempfle, Executive Director SEM 2014 Membership EM conducted comprehensive surveys of its membership in 2002, 2008, and 2014, Survey Report Executive Director Stephen and obtained participation rates of 35% (565 respondents), 30% (547 respondents), S Stuempfle and 32% (545 respondents) respectively. The following report focuses on a selection of questions for which there is generally comparable data across these three years of Whose survey administration. Also included is data for some of the new questions added in the Ethnomusicology? 2014 survey. Due to differences in the structure of the three surveys and in the inclusion President Beverley and wording of questions, some of the numbers presented below are close approxima- Diamond tions based on available data. Section on the Status The report contains five sections: 1) General Characteristics of the Membership; 2) of Women: A Student Members; 3) Members Employed in Colleges and Universities; 4) Members Multivocal History Employed in Museums, Archives, or Other Organizations; and 5) Members’ Perceptions Elizabeth Clendinning of SEM as an Organization. SEM is grateful to its members for taking the time to complete the survey, to its Board of Directors for assistance with the development of questions, and to Jennifer SEM Studebaker (Office Coordinator) for preparing the 2014 online survey instrument and as- Announcements sisting with the compilation of data. 2015 Prizes From the Field 1) General Characteristics of the Membership What is your age? News 2002 2008 2014 Member News Under 21 0.9% 0.6% 0.2% In Memoriam 21-30 17.9% 19.6% 16.1% Hardja Susilo 31-40 23.9% 24.2% 29.4% 41-50 25.3% 19.2% 17.2% Our Back Pages 51-60 18.4% 22.9% 17.9% Conference Calendar 61-70 8.0% 9.8% 12.9% Ethnomusicology Internet Resources Over 70 3.7% 3.9% 6.3% Data indicates a decrease in the percentage of members in the “41-50” age bracket and increases in the “31-40,” “61-70,” and “Over 70” brackets over the past 12 years. -

Assimilationist Language in Cherokee Women's Petitions: a Political Call to Reclaim Traditional Cherokee Culture

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Plan B and other Reports Graduate Studies 5-2016 Assimilationist Language in Cherokee Women's Petitions: A Political Call to Reclaim Traditional Cherokee Culture Jillian Moore Bennion Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Bennion, Jillian Moore, "Assimilationist Language in Cherokee Women's Petitions: A Political Call to Reclaim Traditional Cherokee Culture" (2016). All Graduate Plan B and other Reports. 838. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/gradreports/838 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Plan B and other Reports by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assimilationist Language in Cherokee Women’s Petitions: A Political Call to Reclaim Traditional Cherokee Culture Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters of Arts in American Studies in the Graduate School of Utah State University By Jillian Moore Bennion Graduate Program in American Studies Utah State University 2016 Thesis Committee: Keri Holt, Ph.D., Advisor Melody Graulich, Ph.D. Colleen O’Neill, Ph.D. ASSIMILATIONIST LANGUAGE IN CHEROKEE WOMEN’S PETITIONS: A POLITICAL CALL TO RECLAIM TRADITIONAL CHEROKEE CULTURE By Jillian M. Moore Bennion A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in English Approved: ______________________ ______________________ Dr. Keri Holt Dr. Melody Graulich ______________________ Dr. Colleen O’Neill UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2016 ii Copyright © Jillian M. -

Filipino Americans and Polyculturalism in Seattle, Wa

FILIPINO AMERICANS AND POLYCULTURALISM IN SEATTLE, WA THROUGH HIP HOP AND SPOKEN WORD By STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of American Studies DECEMBER 2008 To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the thesis of STEPHEN ALAN BISCHOFF find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. _____________________________________ Chair, Dr. John Streamas _____________________________________ Dr. Rory Ong _____________________________________ Dr. T.V. Reed ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Since I joined the American Studies Graduate Program, there has been a host of faculty that has really helped me to learn what it takes to be in this field. The one professor that has really guided my development has been Dr. John Streamas. By connecting me to different resources and his challenging the confines of higher education so that it can improve, he has been an inspiration to finish this work. It is also important that I mention the help that other faculty members have given me. I appreciate the assistance I received anytime that I needed it from Dr. T.V. Reed and Dr. Rory Ong. A person that has kept me on point with deadlines and requirements has been Jean Wiegand with the American Studies Department. She gave many reminders and explained answers to my questions often more than once. Debbie Brudie and Rose Smetana assisted me as well in times of need in the Comparative Ethnic Studies office. My cohort over the years in the American Studies program have developed my thinking and inspired me with their own insight and work. -

The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet

Commissioned by BLUE PAPER The Human Relationship with Our Ocean Planet LEAD AUTHORS Edward H. Allison, John Kurien and Yoshitaka Ota CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS: Dedi S. Adhuri, J. Maarten Bavinck, Andrés Cisneros-Montemayor, Michael Fabinyi, Svein Jentoft, Sallie Lau, Tabitha Grace Mallory, Ayodeji Olukoju, Ingrid van Putten, Natasha Stacey, Michelle Voyer and Nireka Weeratunge oceanpanel.org About the High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy The High Level Panel for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) is a unique initiative by 14 world leaders who are building momentum for a sustainable ocean economy in which effective protection, sustainable production and equitable prosperity go hand in hand. By enhancing humanity’s relationship with the ocean, bridging ocean health and wealth, working with diverse stakeholders and harnessing the latest knowledge, the Ocean Panel aims to facilitate a better, more resilient future for people and the planet. Established in September 2018, the Ocean Panel has been working with government, business, financial institutions, the science community and civil society to catalyse and scale bold, pragmatic solutions across policy, governance, technology and finance to ultimately develop an action agenda for transitioning to a sustainable ocean economy. Co-chaired by Norway and Palau, the Ocean Panel is the only ocean policy body made up of serving world leaders with the authority needed to trigger, amplify and accelerate action worldwide for ocean priorities. The Ocean Panel comprises members from Australia, Canada, Chile, Fiji, Ghana, Indonesia, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Mexico, Namibia, Norway, Palau and Portugal and is supported by the UN Secretary-General’s Special Envoy for the Ocean. -

The Policy of Multicultural Education in Russia: Focus on Personal Priorities

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF ENVIRONMENTAL & SCIENCE EDUCATION 2016, VOL. 11, NO. 18, 12613-12628 OPEN ACCESS THE POLICY OF MULTICULTURAL EDUCATION IN RUSSIA: FOCUS ON PERSONAL PRIORITIES a a Natalya Yuryevna Sinyagina , Tatiana Yuryevna Rayfschnayder , a Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration, RUSSIA, ABSTRACT The article contains the results of the study of the current state of multicultural education in Russia. The history of studying the problem of multicultural education has been analyzed; an overview of scientific concepts and research of Russian scientists in the sphere of international relations, including those conducted under defended theses, and the description of technologies of multicultural education in Russia (review of experience, programs, curricula and their effectiveness) have been provided. The ways of the development of multicultural education in Russia have been described. Formulation of the problem of the development of multicultural education in the Russian Federation is currently associated with a progressive trend of the inter- ethnic and social differentiation, intolerance and intransigence, which are manifested both in individual behavior (adherence to prejudices, avoiding contacts with the "others", proneness to conflict) and in group actions (interpersonal aggression, discrimination on any grounds, ethnic conflicts, etc.). A negative attitude towards people with certain diseases, disabilities, HIV-infected people, etc., is another problem at the moment. This situation also -

Minority Versus Majority Cross-Ethnic Friendships Altering Discrimination

Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 59 (2018) 26–35 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jappdp Help or hindrance? Minority versus majority cross-ethnic friendships ☆ T altering discrimination experiences ⁎ Alaina Brenicka, Maja K. Schachnerb,d, , Philipp Jugertc a University of Connecticut, Department of Human Development and Family Studies, 348 Mansfield Rd., U-1058, Storrs, CT 06269-1058, USA b University of Potsdam, Karl-Liebknecht-Str. 24-25, 14476, Potsdam, Germany c University of Duisburg-Essen, Department of Psychology, Universitätsstr. 2, 45141 Essen, Germany d College of Interdisciplinary Educational Research, Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung, Reichpietschufer 50, 10785 Berlin, Germany ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: We examined the interplay between perceived ethnic discrimination (PED) as a risk factor, and cross-ethnic Cross-ethnic friendships friendships as a protective factor in culturally diverse classrooms, and how they relate to the socioemotional Depressive symptoms adjustment of ethnic minority boys and girls. We conducted multi-level analyses of 327 Turkish-heritage ethnic Disruptive behavior minority early-adolescents in Germany (62 classrooms; Mage = 11.59 years, SDage = 0.76). Higher rates of PED Ethnic minority children were associated with more depressive symptoms and disruptive behaviors and lower general life sa- Perceived ethnic discrimination tisfaction—though these effects differed by gender. Unexpectedly, cross-ethnic friendships with ethnic majority Socioemotional adjustment peers exacerbated the negative effects of PED on socioemotional adjustment. This effect was decreased, though, when adolescents perceived the classroom climate to be supportive of intergroup contact toward majority- minority cross-ethnic friendships. Supportive classroom climate also buffered the effects of PED for youth with minority cross-ethnic friends. -

Deciphering the Cultural Code: Perceptual Congruence, Behavioral Conformity, and the Interpersonal Transmission of Culture

Deciphering the Cultural Code: Perceptual Congruence, Behavioral Conformity, and the Interpersonal Transmission of Culture Richard Lu University of California, Berkeley Jennifer A. Chatman University of California, Berkeley Amir Goldberg Stanford University Sameer B. Srivastava University of California, Berkeley Why are some people more successful than others at cultural adjustment? Research on organizational culture has mostly focused on value congruence as the core dimension of cultural fit. We develop a novel and comple- mentary conceptualization of cognitive cultural fit—perceptual congruence, or the degree to which a person can decipher the group's cultural code. We demonstrate that these two cognitive measures are associated with different outcomes: perceptual congruence equips people with the capacity to exhibit behavioral con- formity, whereas value congruence promotes long-term attachment to the organization. Moreover, all three fit measures|perceptual congruence, value congruence, and behavioral cultural fit—are positively related to individual performance. Finally, we show that behavioral cultural fit and perceptual congruence are both influenced by observations of others' behavior, whereas value congruence is less susceptible to peer influence. Drawing on email and survey data from a mid-sized technology firm, we use the tools of computational linguistics and machine learning to develop longitudinal measures of cognitive and behavioral cultural fit. We also take advantage of a reorganization that produced quasi-exogenous shifts in employees' interlocutors to identify the effects of peer influence on behavioral cultural fit. We discuss implications of these findings for research on cultural assimilation, the interplay of structure and culture, and the pairing of surveys with digital trace data. 1 Authors' names blinded for peer review 2 Article submitted to Organization Science; Introduction Whether assimilating to a country or adapting to a new school, people typically seek to fit in cul- turally with their social groups.