The Swamp Land Act in Oregon, 1870-1895

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Report

inaugural report Oregon Cultural Trust fy 2003 – fy 2006 Grant dollars from the Cultural Trust are transformational. In historic Oregon City, they helped bring a more stable operating structure to separate organizations with marginal resources. As a result, we continue to share Oregon’s earliest stories with tens of thousands of visitors, many of them students, every year. —David Porter Clackamas Heritage Partners September 2007 Dear Oregon Cultural Trust supporters and interested Oregonians: With genuine pride we present the Oregon Cultural Trust’s inaugural report from the launch of the Trust in December 2002 through June 30, 2006 (the end of fiscal year 2006). It features the people, the process, the challenges and the success stories. While those years were difficult financial ones for the State, the Trust forged ahead in an inventive and creative manner. Our accomplishments were made possible by a small, agile and highly committed staff; a dedicated, hands-on board of directors; many enthusiastic partners throughout the state; and widespread public buy-in. As this inaugural report shows, the measurable results, given the financial environ- ment, are almost astonishing. In brief, more than $10 million was raised; this came primarily from 10,500 donors who took advantage of Oregon’s unique and generous cultural tax credit. It also came from those who purchased the cultural license plate, those who made gifts beyond the tax credit provision, and from foundations and in-kind corporate gifts. Through June 30, 2006, 262 grants to statewide partners, county coalitions and cultural organizations in all parts of Oregon totaled $2,418,343. -

An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 3-14-1997 An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895 Clarinèr Freeman Boston Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons, and the Public Administration Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Boston, Clarinèr Freeman, "An Historical Perspective of Oregon's and Portland's Political and Social Atmosphere in Relation to the Legal Justice System as it Pertained to Minorities: With Specific Reference to State Laws, City Ordinances, and Arrest and Court Records During the Period -- 1840-1895" (1997). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4992. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6868 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice were presented March 14, 1997, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITTEE APPROVAL: Charles A. Tracy, Chair. Robert WLOckwood Darrell Millner ~ Representative of the Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL<: _ I I .._ __ r"'liatr · nistration of Justice ******************************************************************* ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY by on 6-LL-97 ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Clariner Freeman Boston for the Master of Science in Administration of Justice, presented March 14, 1997. -

Completing a Heartfelt Journey

Clearwater Power Robbi Falls took her trip of a lifetime to Alaska twice — before and after her husband died—to accomplish what the couple originally set out to do together. Photo by Lori Mai Completing a Heartfelt Journey Robbi Falls completes an Alaskan bear hunt in memory of her husband By Lori Mai They met for a drink between Robbi’s the town I grew up in. We needed a place shows. Six years later, they were married. to get away.” By all measures, Bill and Robbi Falls were For the next decade, with Bill’s knowl- complete opposites. She was a showgirl edge and Robbi’s business savvy, the Hunt of a Lifetime at the Stardust Hotel on the Las Vegas couple turned Bill’s humble shop into Rural Idaho provided exactly the kind of Strip. He was a “country bumpkin” from Collision Authority LLC—the largest retreat the couple had been searching for Florida, who traded summers milking chain of professional collision centers in to further their common interest of hunt- cows and skinning catfish for a job in the Nevada. ing and fishing. auto body business “on the wrong side of As the business grew, so did Robbi’s They planned to retire there. the tracks” in Vegas, says Robbi. desire to escape the clamor of Las Vegas. In the meantime, they dreamed of As luck would have it, the two met by The couple bought and remodeled a going on a bear hunt in Alaska. chance when Robbi came into Bill’s shop ranch in Idaho where Robbi lived full For 12 years, they had been in con- to get an estimate for her car. -

Oregon's History

Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden ATHANASIOS MICHAELS Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden by Athanasios Michaels is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted. Contents Introduction 1 1. Origins: Indigenous Inhabitants and Landscapes 3 2. Curiosity, Commerce, Conquest, and Competition: 12 Fur Trade Empires and Discovery 3. Oregon Fever and Western Expansion: Manifest 36 Destiny in the Garden of Eden 4. Native Americans in the Land of Eden: An Elegy of 63 Early Statehood 5. Statehood: Constitutional Exclusions and the Civil 101 War 6. Oregon at the Turn of the Twentieth Century 137 7. The Dawn of the Civil Rights Movement and the 179 World Wars in Oregon 8. Cold War and Counterculture 231 9. End of the Twentieth Century and Beyond 265 Appendix 279 Preface Oregon’s History: People of the Northwest in the Land of Eden presents the people, places, and events of the state of Oregon from a humanist-driven perspective and recounts the struggles various peoples endured to achieve inclusion in the community. Its inspiration came from Carlos Schwantes historical survey, The Pacific Northwest: An Interpretive History which provides a glimpse of national events in American history through a regional approach. David Peterson Del Mar’s Oregon Promise: An Interpretive History has a similar approach as Schwantes, it is a reflective social and cultural history of the state’s diversity. The text offers a broad perspective of various ethnicities, political figures, and marginalized identities. -

NEFF V. PENNOYER. [3 Sawy

1279 Case 17FED.CAS.—81No. 10,083. NEFF V. PENNOYER. [3 Sawy. 274; 15 Am. Law Reg. (N. S.) 367.]1 Circuit Court, D. Oregon. March 9, 1875.2 POWER OF A STATE OVER THE PROPERTY OF NON-RESIDENTS—PROOF OF SERVICE IN CASE OF PUBLICATION—JUDGMENT-ROLL NOT THE WHOLE RECORD—EVIDENCE NECESSARY TO AUTHORIZE ORDER FOR PUBLICATION—EVIDENCE OF CAUSE OF ACTION—A VERIFIED COMPLAINT AN AFFIDAVIT—DILIGENCE TO ASCERTAIN THE PLACE OF RESIDENCE OF NON-RESIDENT DEFENDANT—PROOF OF PUBLICATION OF THE SUMMONS—AVERMENT OF SERVICE IN JUDGMENT ENTRY—PRESUMPTION IN FAVOR OF JURISDICTION. 1. A state has the power to subject the property of non- residents, within its territorial limits, to the satisfaction of the claims of her citizens against such non-residents by any mode of procedure which it may deem proper and convenient under the circumstances, and therefore may, for such purpose authorize a judgment to be given against such non-resident prior to seizure of such property, and with or without notice of the proceeding. [Cited in Hannibal & St. J. R. Co. v. Husen, 95 U. S. 471; Bowman v. Chicago & N. W. Ry. Co., 125 U. S. 465, 8 Sup. Ct. 702.] [Cited in Marsh v. Steele, 9 Neb. 99, 1 N. W. 869.] 2. The proof of service required by section 269 of the Oregon Code to be placed in the judgment-roll includes in the case of service by publication, the affidavit and order for publication as well as the affidavit of the printer to the fact of publication. [Cited in Gray v. -

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge –

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Malheur National Wildlife Refuge Wright’s Point Lawen Lane Ruh-Red Road To Lava Bed Road 13 miles Historic Sod House Ranch Malheur Field Station Peter French Round Barn Restrooms located at Refuge Headquarters, Buena Vista Ponds and Overlook, Krumbo Reservoir, Historic P Ranch Bridge Creek Trail Hiking Trail Undeveloped Area River Trail Auto Tour Route Tour Auto East Canal Road Historic P Ranch (Includes part of Desert Trail on Refuge) Frenchglen Barnyard East Canal Road Springs Footpath Steens Mountain Loop Road Page Springs Campground U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Malheur National Wildlife Refuge Enjoy Your Visit! Trails – Hiking, bicycling, and cross-country We hope you enjoy your visit to Malheur skiing are permitted on designated roads and National Wildlife Refuge. Please observe and trails shown on Refuge maps. Use caution on follow all rules and regulations for your safety, the East Canal Road, it is shared with and to protect wildlife and their habitat. If you vehicular traffic. have a question feel free to contact a member of our staff. Wildlife Viewing – With more than 340 species of birds and 67 species of mammals, Day Use Only – The Refuge is open daily from the Refuge offers prime wildlife viewing. sunrise to sunset. Wildlife checklists are available. Visitor Center, Nature Store and Museum – Fishing and Hunting – Fishing and hunting Brochures, maps, information, recent bird are permitted on Refuge at certain times of sightings and interpretive exhibits are locat- the year. Fishing and hunting brochures are ed at the Refuge headquarters. The Visitor available and lists the designated hunting Center and Nature Store is open Monday and public fishing areas. -

Tom Marsh T O T H E P R O M I S E D L A

marsh output_Doern art 12-04-14 5:45 AM Page 1 MARSH “I am especially pleased to know that Tom Marsh has done painstaking research to bind our history in this tome; perhaps we will learn from our past and forge ahead with positive results for generations to come.” —GERRYFRANK The first comprehensive political history of Oregon, To the Promised Land TO THE PROMISED LAND also examines the social and economic changes the state has pioneered during its almost two hundred years. Highlighting major political figures, campaigns, ballot measures, and the history of legislative sessions, Tom Marsh traces the evolution of Oregon from incorporated territory to a state at the forefront of national environmental and social movements. From Jason Lee’s first letter urging Congress to take possession of the Oregon Country to John Kitzhaber’s precedent-setting third term as governor, from the land frauds of the early 20th century to the state’s land-use planning goals, from the Beach Bill to the Bottle Bill, this book tells Oregon’s story. Featuring interesting trivia, historical photographs, and biographical sketches of key politicians, To the Promised Land is an essential volume for readers interested in Oregon’s history. TOMMARSH taught high school history in Oregon for twenty-eight years. He represented eastern T O M M A R S H Washington County in the state legislature from 1975 to 1979, and has participated in numerous political campaigns over a span of nearly fifty years. He lives in Salem, Oregon. A History of Government ISBN 978-0-87071-657-7 Oregon State University Press and Politics in Oregon Cover design by David Drummond 9 7 8 0 8 7 0 7 1 6 5 7 7 OSU PRESS To the Promised Land A History of Government and Politics in Oregon Tom Marsh Oregon State University Press Corvallis For more information or to purchase the book, visit http://osupress.oregonstate.edu/book/to-promised-land To the Promised Land is dedicated to Katherine and Brynn, Meredith and Megan, and to Judy, my wife. -

Harney County Address List 2021 by Street Name

Harney County Address List 2021 By Street Name STREETNAME DI # UNIT CITY ZIP ACCNUM OWNER Organization Mailing A ST 78896 Drewsey 97904 18108 MOSS, MICHAEL S & MOSS, DAVID A UNKNOWN 792 S JUNTURA AV BURNS OR 97720-2355 A E ST 110 Burns 97720 448 LANDON, KELLY B & SAMANTHA A O UNKNOWN 314 N BROADWAY AV BURNS OR 97720-1748 A E ST 124 Burns 97720 448 LANDON, KELLY B & SAMANTHA A O UNKNOWN 314 N BROADWAY AV BURNS OR 97720-1748 A E ST 138 Burns 97720 448 LANDON, KELLY B & SAMANTHA A O UNKNOWN 314 N BROADWAY AV BURNS OR 97720-1748 A E ST 183 Burns 97720 491 HENSON, JEREMY N & STACEY A UNKNOWN 800 LONG ST SWEET HOME OR 97386-2114 A E ST 195 Burns 97720 491 HENSON, JEREMY N & STACEY A UNKNOWN 800 LONG ST SWEET HOME OR 97386-2114 A E ST 293 Burns 97720 496 TYLER, KIM UNKNOWN P O BOX 562 BURNS OR 97720-0562 A E ST 350 Burns 97720 729 TAYLOR, SHELLEY L UNKNOWN 350 E A ST BURNS OR 97720-1669 A E ST 390 Burns 97720 720 MURRAY, WILL M & HANNAH M UNKNOWN 390 E A ST BURNS OR 97720-1669 A E ST 400 Burns 97720 723 RGA, LLC Rose Garden Apts 1900 NE 3RD ST ##106-291 BEND OR 97701-3854 A E ST 450 Burns 97720 92590 VAVRINEC, MICHAEL & JAMIE L UNKNOWN 317 SIDNEY BAKER ST S ##400-261 KERRVILLE TX 78028-5948 A W ST 90 Burns 97720 457 PRYSE, KEVIN L & DONNA S S UNKNOWN 71816 TURNOUT RD BURNS OR 97720-9343 A W ST 100 18 Burns 97720 463 MC ALLISTER, LOLA A TRUSTEE Marylhurst Apts 105 CARTHAGE AVE EUGENE OR 97404 A W ST 102 17 Burns 97720 463 MC ALLISTER, LOLA A TRUSTEE Marylhurst Apts 105 CARTHAGE AVE EUGENE OR 97404 A W ST 103 1 Burns 97720 477 MC ALLISTER, LOLA -

Diamond Loop Back Country Byway, This Brochure Offers the Option of Three Starting Points: You Will Find a Patchwork of High Desert Terrains

USFWS • Harney County • ODOT BLM Introduction How to Use this Brochure National Back As you travel the Diamond Loop Back Country Byway, This brochure offers the option of three starting points: you will find a patchwork of high desert terrains. From • Near Princeton on State Highway 78 (north) Country Byway the deep blues of mountain vistas and the dusky sage- • The junction of State Highway 205 and Diamond covered hills, to the red rimrock canyons and the grassy Lane (west) reaches of marshes and valleys, you will find 69 miles of • Frenchglen on State Highway 205 (south) new adventure waiting for you. Check the map in this brochure or at the byway Diamond Loop interpretive shelters to determine your location. Then If you are a wildlife watcher, keep an eye out for wild choose the route that will take you to the features you horses, mule deer, or pronghorn antelope. Bring along want to explore and some you didn’t even know existed. your binoculars to spot the waterfowl, shorebirds, hawks, and eagles that traverse the Pacific Flyway through the area. Whether you are exploring a lava flow, stopping at small historic towns, or passing the ranches scattered throughout the valleys between the Steens and Riddle mountains, you will travel back country roads that lead to attractions right out of the ‘Old West.” Narrows (Photo by Marcus Haines) Frenchglen (Photo by Bill Renwick) Little Red Cone, Diamond Craters For further information, contact: Tips for Travelers • Road conditions in the area can change without Bureau of Land Management Burns District notice. -

Sin, Scandal and Substantive Due Process: Personal Jurisdiction and Pennoyer Reconsidered Wendy Collins Perdue University of Richmond, [email protected]

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Law Faculty Publications School of Law 1987 Sin, Scandal and Substantive Due Process: Personal Jurisdiction and Pennoyer Reconsidered Wendy Collins Perdue University of Richmond, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/law-faculty-publications Part of the Civil Procedure Commons, and the Jurisdiction Commons Recommended Citation Wendy Collins Perdue, Sin, Scandal and Substantive Due Process: Personal Jurisdiction and Pennoyer Reconsidered, 62 Wash. L. Rev. 479 (1987) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SIN, SCANDAL, AND SUBSTANTIVE DUE PROCESS: PERSONAL JURISDICTION AND PENNOYER RECONSIDERED Wendy Collins Perdue* "Confusion now hath made its masterpiece," 1 exclaims Macduff in Act II of Macbeth. The same might be said of the venerable case, Pennoyer v. Neff.2 Over 100 years after issuing Pennoyer the Supreme Court is still laboring to articulate a coherent doctrine of personal jurisdiction within the framework established by that opinion. Recently, the Court has become particularly interested in personal jurisdiction and has dealt with the issue seven times in the last four years. 3 Yet despite this growing body of case law, the doctrinal underpinnings remain elusive. The Court continues to treat geographic boundaries as central to the interests protected by personal jurisdiction, but has never satisfactorily explained why they are so central or what interest the doctrine of personal jurisdiction is intended to protect. -

The Building They Shaped the Hatfield Courthouse at Twenty by Doug Pahl Inston Churchill Once Observed, “We Shape and $33.32 Million for Construction

THE U.S. DIstRICT COURT OF OREGON HIstORICAL SOCIETY NEWSLEttER The building they shaped The Hatfield Courthouse at Twenty By Doug Pahl inston Churchill once observed, “We shape and $33.32 million for construction. Wour buildings, and afterward our buildings Reversing course at that advanced stage took shape us.” Twenty years ago, Ninth Circuit Court nerve and wasn’t without risk. But by late fall of Appeals Chief Judge Proctor Hug stood in the 1990, an abrupt but thoughtful change of course gleaming green lobby of the Mark O. Hatfield was necessary. It occurred thanks to the foresight U.S. Courthouse and reminded us of Churchill’s of our judges, led by Chief Judge Owen M. Pan- wisdom. It was November 13, 1997, and an ner, Judge James A. Redden, and Judge Marsh. It unprecedented group of dignitaries gathered to was clear the proposed annex property would not celebrate and dedicate Portland’s first new court- accommodate the court’s minimum space require- house since 1933. ments under newly-announced federal courthouse Judges, court staff, administration officials, design requirements. Judge Redden was selected designers, and artists, all led by Judge Malcolm Continue on page 2 F. Marsh, had indeed shaped an impressive build- ing with great care, intention, and respect. As the Hatfield Courthouse completes its teen years, it is timely to reflect on what inspired it, why its planners shaped it the way they did, and how it shapes those who seek justice and those who work diligently to dispense it. Initially, let us remember what could have been— in fact, what almost was. -

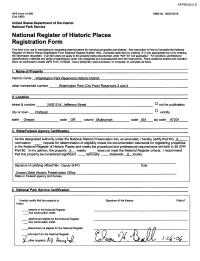

Fo /Vj\ Off , ,, , F » a T Q -X Other (Explain): /V U /Tcce^L *^Wc Uv^V^ /*

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 10024-0018 (Oct.1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Washington Park Reservoirs Historic District other names/site number Washington Park (City Park) Reservoirs 3 and 4 2. Location street & number 2403 S.W. Jefferson Street not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97201 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property X meets __ does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant __ nationally __ statewide X locally.