Tom Marsh T O T H E P R O M I S E D L A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

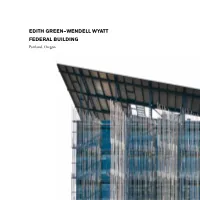

EDITH GREEN–WENDELL WYATT FEDERAL BUILDING Portland, Oregon Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in Portland, Oregon, Was Renovated Under the U.S

EDITH GREEN–WENDELL WYATT FEDERAL BUILDING Portland, Oregon Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building in Portland, Oregon, was renovated under the U.S. General Services Administration’s Design Excellence Program, an initiative to create and preserve outstanding public buildings that will be used and enjoyed now and by future generations of Americans. April 2017 EDITH GREEN–WENDELL WYATT FEDERAL BUILDING Portland, Oregon 6 Origins of Edith Green-Wendell Wyatt Federal Building 10 Preparing for Modernization 16 EGWW’s Mutually Reinforcing Solutions 24 The Portfolio Perspective 28 EGWW’s Arts Legacy 32 The Design and Construction Team 39 U.S. General Services Administration and the Design Excellence Program 2 Each facade is attuned to daylight angles; the entire solution is based on the way the sun moves around the building. Donald Eggleston Principal, SERA 3 4 5 ORIGINS OF EDITH GREEN-WENDELL WYATT FEDERAL BUILDING At the start of the Great Depression, the Public Buildings Act of 1959 initiated half a million civilians worked for the hundreds more. Of the 1,500 federally United States. In 1965, approximately owned buildings that PBS manages today, 2.7 million Americans held non-uniformed more than one-third dates between 1949 jobs. Federal civilian employment multi- and 1979. plied five times in less than four decades thanks to the New Deal, and Edith Green- GSA’s mid-century building boom almost Wendell Wyatt Federal Building (EGWW) unanimously embodied the democratic stands 18 stories above Portland, Oregon, ideas and sleek geometry of modernist as a long-drawn consequence of that architecture. Not only had modernism historic transformation. -

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012

Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Jennifer E. Manning Information Research Specialist Colleen J. Shogan Deputy Director and Senior Specialist November 26, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL30261 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress Women in the United States Congress: 1917-2012 Summary Ninety-four women currently serve in the 112th Congress: 77 in the House (53 Democrats and 24 Republicans) and 17 in the Senate (12 Democrats and 5 Republicans). Ninety-two women were initially sworn in to the 112th Congress, two women Democratic House Members have since resigned, and four others have been elected. This number (94) is lower than the record number of 95 women who were initially elected to the 111th Congress. The first woman elected to Congress was Representative Jeannette Rankin (R-MT, 1917-1919, 1941-1943). The first woman to serve in the Senate was Rebecca Latimer Felton (D-GA). She was appointed in 1922 and served for only one day. A total of 278 women have served in Congress, 178 Democrats and 100 Republicans. Of these women, 239 (153 Democrats, 86 Republicans) have served only in the House of Representatives; 31 (19 Democrats, 12 Republicans) have served only in the Senate; and 8 (6 Democrats, 2 Republicans) have served in both houses. These figures include one non-voting Delegate each from Guam, Hawaii, the District of Columbia, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Currently serving Senator Barbara Mikulski (D-MD) holds the record for length of service by a woman in Congress with 35 years (10 of which were spent in the House). -

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: an Historical Chronology 1969-2019

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 By Dr. James (Jim) Davis Oregon State Council for Retired Citizens United Seniors of Oregon December 2020 0 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Yearly Chronology of Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy 5 1969 5 1970 5 1971 6 1972 7 1973 8 1974 10 1975 11 1976 12 1977 13 1978 15 1979 17 1980 19 1981 22 1982 26 1983 28 1984 30 1985 32 1986 35 1987 36 1988 38 1989 41 1990 45 1991 47 1992 50 1993 53 1994 54 1995 55 1996 58 1997 60 1998 62 1999 65 2000 67 2001 68 2002 75 2003 76 2004 79 2005 80 2006 84 2007 85 2008 89 1 2009 91 2010 93 2011 95 2012 98 2013 99 2014 102 2015 105 2016 107 2017 109 2018 114 2019 118 Conclusion 124 2 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 Introduction It is my pleasure to release the second edition of the 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019, a labor of love project that chronicles year-by-year the major highlights and activities in Oregon’s senior and disability policy development and advocacy since 1969, from an advocacy perspective. In particular, it highlights the development and maintenance of our nationally-renown community-based long term services and supports system, as well as the very strong grassroots, coalition-based advocacy efforts in the senior and disability communities in Oregon. -

Senate Republican Conference John Thune

HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE JOHN THUNE 115th Congress Revised January 2017 HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE Table of Contents Preface ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1 Rules of the Senate Republican Conference ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....2 A Service as Chairman or Ranking Minority Member ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 B Standing Committee Chair/Ranking Member Term Limits ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 C Limitations on Number of Chairmanships/ Ranking Memberships ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 D Indictment or Conviction of Committee Chair/Ranking Member ....... ....... ....... .......5 ....... E Seniority ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... 5....... ....... ....... ...... F Bumping Rights ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 G Limitation on Committee Service ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ...5 H Assignments of Newly Elected Senators ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 Supplement to the Republican Conference Rules ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 6 Waiver of seniority rights ..... -

November 3, 2020 the Honorable Kate Brown Governor of Oregon the State Capitol 900 Court Street, NE Salem, Oregon 97301 Dear

November 3, 2020 The Honorable Kate Brown Governor of Oregon The State Capitol 900 Court Street, NE Salem, Oregon 97301 Dear Governor Brown, We understand that you're hearing from the alcohol industry regarding your proposed beer and wine tax legislation for the 2021 session. We are writing to make clear that our organizations wholly support prioritizing the health and wellness of our communities by raising the price of alcohol and using that revenue to make significant investments in addiction prevention, treatment and recovery services. In the last twenty years Oregon's alcohol mortality rate has increased 34%, leading to five deaths per day resulting from alcohol, while Oregon's beer and wine industries have enjoyed some of the lowest taxes in the nation. The economic cost of this crisis is staggering. The Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission's Statewide Strategic Plan calculated that Oregon is spending an estimated $6.7 billion per year on issues related to substance misuse, the majority of which is a result of harmful alcohol use. State spending on substance use has quadrupled since 2005 and consumed nearly 17% of the state budget in 2017, however less than 1% of those funds are used to prevent, treat and support the recovery of people with substance use disorder. For far too long, Oregon has ranked as one of the worst states in the nation in addressing the disease of addiction, and the absence of adequate funding and attention to this crisis has put an undue financial burden on our healthcare, public safety and criminal justice workforces. -

View / Open Chapmangraves, Camas1.Pdf

How Activism during the Vietnam Era Influenced Change in the Student Role on Campus Camas ChapmanGraves The University in Peace and War: HC 421 Professor Suzanne Clark March 13, 2005 ChapmanGraves 2 In describing United States student activists of the 1990’s, Kate Zernike says they are “a very different pack of protesters from the long-haired, antiestablishment dissenters of the past”.1 This seems to be a common attitude toward the student protesters of the 1960’s. The reality of 1960’s protests was not however what many may have imagined. While protests of the sixties may have included token hippies and a few violent dissenters, student protesters were not antiestablishment. On many campuses they even had their own form of establishment, and many members of this establishment would go on to play an important role in the United States government. At the University of Oregon, the student protest movement and its leaders became an integral part of student government. Not only was student government involved in protests, but the official actions taken by the University of Oregon student government, the Associated Students of the University of Oregon (ASUO), during this time reflect the attitudes of the student protesters. Students of the sixties wanted control over myriad aspects of their lives, and used the establishment of student government to fight for this control. This was clearly seen through specific actions taken by student government in the late 1960’s in an attempt to gain control over their education. At the University of Oregon, student government and student protest went hand in hand. -

New Congress on Line to Be Next Big Brother

New Congress on Line to be Next Big Brother By Bill Hobby Hooray for the new Congress. They promised to take government off our back, and they've put it in our living room. They promised to free us from regulation, and they've concocted one that can deprive some unwitting computer nerds of their liberty. The amendment attached to an overhaul of federal communications law by the Senate Commerce Committee sets fines up to $100,000 and jail terms of up to two years for anyone who transmits material that is "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent" over the Internet. Welcome, thought police. As one columnist, Charles Levendosky of the Casper (Wyoming) Star-Tribune, put it, "It would melt the promise of this electronic Gutenberg." Many of us are just now discovering the wonders of cyberspace as presented through the Internet. We're just learning to pull up reproductions of paintings in the Louvre, reference material from the Library of Congress, bills up for consideration in the Texas Legislature. We are travelers in a fantastic new world of knowledge and information. This wonderful worldwide network of computers can answer our questions in seconds, whether we want to know about ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics or what happened today in the O.J. Simpson trial So naturally our Big Brothers in Congress couldn't leave us alone. Under the guise of protecting children from smut, the Senate has adopted one of the most draconian invasions of privacy ever. It has never been clear to me why the government considers that it owns the airwaves. -

("DSCC") Files This Complaint Seeking an Immediate Investigation by the 7

COMPLAINT BEFORE THE FEDERAL ELECTION CBHMISSIOAl INTRODUCTXON - 1 The Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee ("DSCC") 7-_. J _j. c files this complaint seeking an immediate investigation by the 7 c; a > Federal Election Commission into the illegal spending A* practices of the National Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee (WRSCIt). As the public record shows, and an investigation will confirm, the NRSC and a series of ostensibly nonprofit, nonpartisan groups have undertaken a significant and sustained effort to funnel "soft money101 into federal elections in violation of the Federal Election Campaign Act of 1971, as amended or "the Act"), 2 U.S.C. 5s 431 et seq., and the Federal Election Commission (peFECt)Regulations, 11 C.F.R. 85 100.1 & sea. 'The term "aoft money" as ueed in this Complaint means funds,that would not be lawful for use in connection with any federal election (e.g., corporate or labor organization treasury funds, contributions in excess of the relevant contribution limit for federal elections). THE FACTS IN TBIS CABE On November 24, 1992, the state of Georgia held a unique runoff election for the office of United States Senator. Georgia law provided for a runoff if no candidate in the regularly scheduled November 3 general election received in excess of 50 percent of the vote. The 1992 runoff in Georg a was a hotly contested race between the Democratic incumbent Wyche Fowler, and his Republican opponent, Paul Coverdell. The Republicans presented this election as a %ust-win81 election. Exhibit 1. The Republicans were so intent on victory that Senator Dole announced he was willing to give up his seat on the Senate Agriculture Committee for Coverdell, if necessary. -

Melody Rose, Ph.D

MELODY ROSE, PH.D. linkedin.com/in/melody-rose Melody Rose has a distinguished 25-year career in higher education. The first in her family to achieve a college degree, Rose is passionate about improving educational access for all, identifying cutting-edge innovations, and driving data- driven, student- focused change. She is currently the owner and principal of Rose Strategies, LLC. There she provides consulting services to universities, focusing on revenue development, strategic communications, sound governance, and organizational development. Before forming her firm, Rose was a higher education leader in Oregon for more than two decades, serving the Oregon University System for 19 years, culminating in her position as Chancellor, and then serving as President of a small Catholic liberal arts university. Rose started her career as a faculty member at Portland State University (PSU) in 1995, rising from fixed-term instructor to Professor and Chair of the Division of Political Science. She founded and directed PSU’s Center for Women’s Leadership, changing the face of Oregon’s public service sector. She also served as Special Assistant to the PSU President working on university restructuring before being selected as PSU’s Vice Provost for Academic Programs and Instruction and Dean of Undergraduate Studies. In that role, she advanced the university’s position in online educational programs through the creation of the PSU Center for Online Learning. In 2012, she was named Vice Chancellor for Academic Strategies of the Oregon University System, the chief academic officer for the state’s seven public universities. During her brief service in this role, Rose worked to improve transfer pathways for community college students as the Primary Investigator on a Lumina Foundation-funded grant and helped to expand the System’s online learning inventory through an innovative agreement with the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE). -

The Salmon Summit1

THE SALMON SUMMIT1 Introduction The story of the Salmon Summit is the prologue to a story that will continue unfolding in the halls of Congress, federal agencies and the courts for years to come. It describes an effort to collaboratively develop a plan that would protect several species and subspecies of salmon in the Pacific Northwest, thereby precluding the necessity of having the species listed under the Endangered Species Act. Since the species were ultimately listed, the periodic collaborations that continue under the guise of the Salmon Summit are focused on developing a viable recovery plan for the various species. The plight of the Pacific Northwest salmon species is not a new issue. In fact, during the 1980's, more than $1.5 billion was spent on solving the problem, without much success. The issue is made more complex by the unique claims and rights of Indian tribes to the fishery resource. The issue is also fraught with tensions between the federal government and regional interests, with regional interests striving hard to maintain their control over the issue. It is clear to all involved that if nothing is done soon to protect the remaining salmon, then the various species will go extinct. Background The Columbia River Basin and the Salmon The Columbia River has its headwaters in Canada and is over 1250 miles long (see Figure 1). Its main tributary, the Snake River, is over 1000 miles long, and the total length of the Columbia and its tributaries is about 14,000 miles. The entire Columbia River basin is larger than the country of France, covering 260,000 acres. -

Bush House Today Lies Chiefly in Its Rich, Unaltered Interior,Rn Which Includes Original Embossed French Wall Papers, Brass Fittings, and Elaborate Woodwork

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oregon COUNTTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mari on INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applica#ie\s&ctipns) / \ ' •• &•••» JAN 211974 COMMON: /W/' .- ' L7 w G I 17 i97«.i< ——————— Bush (Asahel) House —— U^ ——————————— AND/OR HISTORIC: \r«----. ^ „. I.... ; „,. .....,.„„.....,.,.„„,„,..,.,..,..,.,, , ,, . .....,,,.,,,M,^,,,,,,,,M,MM^;Mi,,,,^,,p'K.Qic:r,£: 'i-; |::::V^^:iX.::^:i:rtW^:^ :^^ Sii U:ljif&:ii!\::T;:*:WW:;::^^ STREET AND NUMBER: "^s / .•.-'.••-' ' '* ; , X •' V- ; '"."...,, - > 600 Mission Street s. F. W J , CITY OR TOWN: Oregon Second Congressional Dist. Salem Representative Al TJllman STATE CODE COUNT ^ : CO D E Oreeon 97301 41 Marien Q47 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC r] District |t] Building SO Public Public Acquisit on: E Occupied Yes: r-, n . , D Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Process ( _| Unoccupied -j . —. _ X~l Unrestricted [ —[ Object | | Both [ | Being Consider ea Q Preservation work ^~ ' in progress ' — I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government | | Park [~] Transportation l~l Comments | | Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) Q Educational d] Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment GsV Museum QJ] Scientific ...................... OWNER'S NAME: Ul (owner proponent of nomination) P ) ———————City of Salem————————————————————————————————————————— - )