The Salmon Summit1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: an Historical Chronology 1969-2019

50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 By Dr. James (Jim) Davis Oregon State Council for Retired Citizens United Seniors of Oregon December 2020 0 Table of Contents Introduction Page 3 Yearly Chronology of Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy 5 1969 5 1970 5 1971 6 1972 7 1973 8 1974 10 1975 11 1976 12 1977 13 1978 15 1979 17 1980 19 1981 22 1982 26 1983 28 1984 30 1985 32 1986 35 1987 36 1988 38 1989 41 1990 45 1991 47 1992 50 1993 53 1994 54 1995 55 1996 58 1997 60 1998 62 1999 65 2000 67 2001 68 2002 75 2003 76 2004 79 2005 80 2006 84 2007 85 2008 89 1 2009 91 2010 93 2011 95 2012 98 2013 99 2014 102 2015 105 2016 107 2017 109 2018 114 2019 118 Conclusion 124 2 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019 Introduction It is my pleasure to release the second edition of the 50 Years of Oregon Senior and Disability Policy and Advocacy: An Historical Chronology 1969-2019, a labor of love project that chronicles year-by-year the major highlights and activities in Oregon’s senior and disability policy development and advocacy since 1969, from an advocacy perspective. In particular, it highlights the development and maintenance of our nationally-renown community-based long term services and supports system, as well as the very strong grassroots, coalition-based advocacy efforts in the senior and disability communities in Oregon. -

Melody Rose, Ph.D

MELODY ROSE, PH.D. linkedin.com/in/melody-rose Melody Rose has a distinguished 25-year career in higher education. The first in her family to achieve a college degree, Rose is passionate about improving educational access for all, identifying cutting-edge innovations, and driving data- driven, student- focused change. She is currently the owner and principal of Rose Strategies, LLC. There she provides consulting services to universities, focusing on revenue development, strategic communications, sound governance, and organizational development. Before forming her firm, Rose was a higher education leader in Oregon for more than two decades, serving the Oregon University System for 19 years, culminating in her position as Chancellor, and then serving as President of a small Catholic liberal arts university. Rose started her career as a faculty member at Portland State University (PSU) in 1995, rising from fixed-term instructor to Professor and Chair of the Division of Political Science. She founded and directed PSU’s Center for Women’s Leadership, changing the face of Oregon’s public service sector. She also served as Special Assistant to the PSU President working on university restructuring before being selected as PSU’s Vice Provost for Academic Programs and Instruction and Dean of Undergraduate Studies. In that role, she advanced the university’s position in online educational programs through the creation of the PSU Center for Online Learning. In 2012, she was named Vice Chancellor for Academic Strategies of the Oregon University System, the chief academic officer for the state’s seven public universities. During her brief service in this role, Rose worked to improve transfer pathways for community college students as the Primary Investigator on a Lumina Foundation-funded grant and helped to expand the System’s online learning inventory through an innovative agreement with the Western Interstate Commission for Higher Education (WICHE). -

Individuals Oregon Arts Commission Governor Arts Award Recipients

Individuals Oregon Arts Commission Governor Arts Award Recipients - 1977 to 2007 Sorted alphabetically by last name Note: some information is not available First Name First Name (2) Last Year Governor Organization City Description Obo (d) Addy 1993 Barbara Roberts Portland African drummer and performer John Alvord 1989 Neil Goldschmidt Eugene Arts patron Pamela Hulse Andrews 2003 Ted Kulongoski Bend Arts publisher Shannon Applegate 2007 Ted Kulongoski Yoncalla Writer & lecturer Ray Atkeson 1986 Victor Atiyeh Portland Photographer Lorie Baxter 1999 John Kitzhaber Pendleton Community arts leaders Newspaper editor, community Amy (d) Bedford 1988 Neil Goldschmidt Pendleton leader & arts patron Pietro (d) Belluschi 1986 Victor Atiyeh Portland Architect Visual artist & leader in arts Eugene (d) Bennett 2002 John Kitzhaber BOORA Architects Jacksonville advocate Oregon Shakespeare William Bloodgood 2002 John Kitzhaber Festival Ashland Scenic designer Banker & collector of Native Doris (d) Bounds 1986 Victor Atiyeh Hermiston American materials Frank Boyden 1995 John Kitzhaber Otis Ceramicist, sculptor & printmaker John Brombaugh 1996 John Kitzhaber Springfield Organ builder Jazz musician & community arts Mel Brown 2002 John Kitzhaber Portland leader Richard Lewis Brown 2005 Ted Kulongoski Portland Collector & arts patron Louis (d) Bunce 1978 Robert Straub Portland WPA painter Dunbar (d) Jane (d) Carpenter 1985 Victor Atiyeh Medford Arts patrons Maribeth Collins 1978 Robert Straub Portland Arts patron First Name First Name (2) Last Year Governor -

Metro Councilor Tanya Collier

Metro Councilor Tanya Collier District 9, 1986 to 1993 Oral History ca. 1993 Tanya Collier Metro Councilor, District 9 1986 – 1993 Tanya Collier was born in Tulare, California in 1946, and moved to Portland, Oregon with her family in 1950, where she attended a number of public grade schools, including West Gresham, Lane, Kelly, Binnsmead, and Kellogg, before enrolling in St. Anthony’s Catholic School. She graduated from John Marshall High School in southeast Portland, and went on to earn an Associate of Arts degree in Political Science at Clackamas Community College in 1973. In 1975, Ms. Collier earned a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Portland State University (PSU), and received a Master’s of Public Administration degree from PSU in 1979. Ms. Collier’s path to elected office was marked by both professional and voluntary activities in the public and non-profit sectors. Over a ten year period, she gained valuable experience in public policy development through her work as executive director of Multnomah County Children’s Commission (1976-1978); as staff assistant to Multnomah County Commissioner Barbara Roberts (1978); as special project manager at the City of Portland’s Bureau of Budget and Management (1980); and as assistant director and later, director of Multnomah County’s Department of Intergovernmental Relations and Community Affairs (1980-1983). In October 1983, she was hired as the general manager of Portland Energy Conservation, Inc. (PECI) – a non-profit corporation charged with implementing the private sector goals of the City of Portland’s Energy policy. In March 1985, Ms. Collier applied her special skills in group negotiation to her position as labor representative with the Oregon Nurses Association – a position she retained while holding elected office at Metro. -

Senate Joint Resolution 24 Ordered by the Senate July 6 Including Senate Amendments Dated July 6

73rd OREGON LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY--2005 Regular Session A-Engrossed Senate Joint Resolution 24 Ordered by the Senate July 6 Including Senate Amendments dated July 6 Sponsored by Senators B STARR, METSGER; Senators ATKINSON, BEYER, DEVLIN, GEORGE, MORSE, NELSON, C STARR SUMMARY The following summary is not prepared by the sponsors of the measure and is not a part of the body thereof subject to consideration by the Legislative Assembly. It is an editor′s brief statement of the essential features of the measure. Directs Port of Portland to [rename] name terminal at Portland International Airport [“Victor G. Atiyeh Portland International Airport.”] after Victor G. Atiyeh. Expresses resolve to rename Oregon Department of Human Services headquarters building Barbara Roberts Human Ser- vices Building. 1 JOINT RESOLUTION 2 Whereas both Victor G. Atiyeh and Barbara Roberts have set precedents when elected to serve 3 as the Governor of Oregon; and 4 Whereas Victor G. Atiyeh is a native Oregonian, a lifelong Washington County resident, the 5 husband of Dolores and the father of two children; and 6 Whereas Victor G. Atiyeh honorably served in the Oregon Legislative Assembly both in the 7 House of Representatives and the Senate; and 8 Whereas Victor G. Atiyeh, in his long-term service to the Boy Scouts of America, holds the 9 highest council and regional adult leadership awards; and 10 Whereas Victor G. Atiyeh won a decisive victory, attracting 55 percent of the vote in the 11 Oregon Governor′s race in 1978; and 12 Whereas Victor G. Atiyeh was the first elected governor of Arab descent in the United States; 13 and 14 Whereas Victor G. -

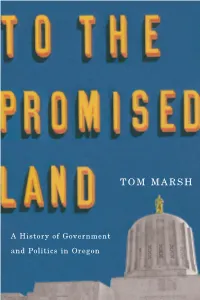

Tom Marsh T O T H E P R O M I S E D L A

marsh output_Doern art 12-04-14 5:45 AM Page 1 MARSH “I am especially pleased to know that Tom Marsh has done painstaking research to bind our history in this tome; perhaps we will learn from our past and forge ahead with positive results for generations to come.” —GERRYFRANK The first comprehensive political history of Oregon, To the Promised Land TO THE PROMISED LAND also examines the social and economic changes the state has pioneered during its almost two hundred years. Highlighting major political figures, campaigns, ballot measures, and the history of legislative sessions, Tom Marsh traces the evolution of Oregon from incorporated territory to a state at the forefront of national environmental and social movements. From Jason Lee’s first letter urging Congress to take possession of the Oregon Country to John Kitzhaber’s precedent-setting third term as governor, from the land frauds of the early 20th century to the state’s land-use planning goals, from the Beach Bill to the Bottle Bill, this book tells Oregon’s story. Featuring interesting trivia, historical photographs, and biographical sketches of key politicians, To the Promised Land is an essential volume for readers interested in Oregon’s history. TOMMARSH taught high school history in Oregon for twenty-eight years. He represented eastern T O M M A R S H Washington County in the state legislature from 1975 to 1979, and has participated in numerous political campaigns over a span of nearly fifty years. He lives in Salem, Oregon. A History of Government ISBN 978-0-87071-657-7 Oregon State University Press and Politics in Oregon Cover design by David Drummond 9 7 8 0 8 7 0 7 1 6 5 7 7 OSU PRESS To the Promised Land A History of Government and Politics in Oregon Tom Marsh Oregon State University Press Corvallis For more information or to purchase the book, visit http://osupress.oregonstate.edu/book/to-promised-land To the Promised Land is dedicated to Katherine and Brynn, Meredith and Megan, and to Judy, my wife. -

Résumé 2009 – Present, Principal BDS Planning & Urban Design BRIAN DOUGLAS SCOTT, Ph.D

WORK HISTORY Résumé 2009 – present, Principal BDS Planning & Urban Design BRIAN DOUGLAS SCOTT, Ph.D. 2008 – 09. Director of Urban Design EDAW|AECOM Principal, BDS Planning & Urban Design 2004 – 08. Director, Northwest Operations MIG, Inc. Brian Scott has 35 + years of experience in comprehensive community development, 1995 – 2007. Adjunct Professor with emphasis in consensus facilitation, strategic planning, urban design, downtown Portland State University, College of Urban & revitalization, public engagement, transportation, land use, and public policy. Mr. Public Affairs Scott’s unique strengths include a capacity to build consensus and unlikely coalitions, 2002 – 03. Executive Director communicate complex information, demonstrate leading ideas, and shape policy. Portland Schools Real Estate Trust 2001 – 02. Programs Director Mr. Scott is a respected facilitator of contentious issues. He has led dozens of multi- Innovation Partnership faceted design and planning projects throughout the Pacific Northwest and across the 1984 – 2001. President & Executive Director country. Mr. Scott specializes in projects that call for his facilitation skills, political Livable Oregon + Oregon Downtown Development Association instincts, and focus on implementation. 1982 – 84. Downtown Planner City of Raleigh, NC With experience in the nonprofit, public, and private sectors, Mr. Scott is able to combine design and planning expertise with direct management experience and 1980 – 82. Consultant Town of Manteo, NC practiced communication skills. As a result, he is known for implementable visionary plans, with strong community and stakeholder support. EDUCATION Ph.D., Urban Studies Long a visionary and thought leader on urban development issues, Mr. Scott has Portland State University dedicated his career to helping people make cities work better for people as a means of Certificate, Nonprofit Management protecting the countryside and sustaining the earth for future generations. -

Annual Report July 1, 2017- June 30, 2018 You and the Oregon State Capitol Foundation

Annual Report July 1, 2017- June 30, 2018 You and the Oregon State Capitol Foundation Our shared vision and mission is that Oregonians connect with their Capitol as a beautiful, vibrant place to engage with history and democracy. With your support, the Oregon State Capitol Foundation connects Oregonians to a shared heritage, enhances the beauty of the Capitol and engages E . citizens in their democracy. v e e g n ta ts i a r t e t h h se e r C ve ap di it ’s ol on con reg nect visitors to O At your service OFFICERS 2017-2018 BOARD OF DIRECTORS Joan Plank Sen. Lee Beyer Hon. Jason Allmand Dan Jarman Chair Sen. Arnie Roblan Atkinson Hon. Anthony Meeker Kim Duncan Sen. Chuck Thomsen Frankie Bell Ed Schoaps Vice chair Rep. Brian Clem Hon. Jane Cease Hon. Norm Smith Fred Neal Herb Colomb Secretary Rep. John Huffman Gerry Thompson Judy Hall Bruce Bishop Rep. Rick Lewis Fred VanNatta Treasurer Rep. Ron Noble Nan Heim Hon. Gary Wilhelms EMERITUS BOARD CONTACT US Hon. Verne Duncan PO Box 13472, Salem OR 97309 Hon. Norma Paulus 1288 Court St NE, Salem OR 97301 Phone: 503-363-1859 | Fax: 503-364-9919 [email protected] oregoncapitolfoundation.org 2 The Oregon State Capitol Foundation Capitol celebrating Oregon’s 159th birthday. achieves its mission by providing The rare privilege to see this historically educational and cultural programs, events significant document in person was made and displays, preserving history and possible thanks to visionaries like you. supporting improvements that contribute to the dignity and beauty of the building Your generosity helps provide free, family- and grounds. -

Organizations Oregon Arts Commission Governor Arts Award

Organizations Oregon Arts Commission Governor Arts Award Recipients - 1977 to 2007 Sorted alphabetically Note: some information is not available Organization Year Governor City Description Albany Creative Arts Guild 1977 Robert Straub Art in Public Places 1988 Neil Goldschmidt Bend Arts in Oregon Council 1977 Robert Straub Bank of America 1999 John Kitzhaber Corporate arts supporters Design of cultural facilities and arts BOORA Architects 1996 John Kitzhaber Portland patronage Brooks-Scanlon Inc 1980 Victor Atiyeh Corporate support for the arts CALYX 1996 John Kitzhaber Corvallis Feminist press Chamber Music Northwest 1995 John Kitzhaber Portland Chamber music programs Children's Educational Theatre 1994 Barbara Roberts Salem Outstanding theater programs for youth For the development of the Hult Center for Citizens of Eugene 1983 Victor Atiyeh Portland the Performing Arts Contemporary Crafts Association 1980 Victor Atiyeh Portland Crafts programming Cultural Planning Taskforces 2002 John Kitzhaber Cultural leadership Eugene Ballet Company 1996 John Kitzhaber Eugene Dance touring efforts Eugene Summer Festival of Music 1981 Victor Atiyeh Eugene (precursor of the Oregon Bach Festival) Friends of Timberline 1987 Neil Goldschmidt Mt Hood Public art & preservation Interstate Firehouse Cultural Center 1992 Barbara Roberts Portland Community arts programs Jefferson High School Arts Program 1978 Robert Straub Portland Arts education Kaiser Permanente 1986 Victor Atiyeh Corporate arts supporter Meyer Memorial Trust 1992 Barbara Roberts Portland -

Women's Representation in Oregon

Women’s Representation in Oregon Parity Ranking: 13th of 50 Levels of Government Score of 23: Seven points for secretary of state and attorney general, 3 points for the percentage Statewide Executives of U.S. House members who are women, 8 for Female governors: Barbara Roberts (1991-95) the percentage of state legislators who are women, 1 for the speaker of the house, and 4 Female statewide elected executives: 2 of 5 points for Mayors Kitty Piercy of Eugene and (secretary of state and attorney general) Anna Peterson of Salem. Number of women to have held statewide elected Quick Facts executive office: 6 Oregon was an early leader in electing women, but the state has not elected a woman to the Congress U.S. Senate since Maurine Brown Neuberger (D) U.S. Senate: 0 of 2 seats are held by women served one term after her 1960 election. No major party has nominated a woman to run for U.S. House: 1 of 5 seats is held by a woman Senate for more than two decades. In its history, Oregon has elected five women to Trending the U.S. House and one to the U.S. Senate. Although women’s representation in the state State Legislature legislature is strong relative to other states (ranking 13th of 50), it has declined since 2002, Percentage women: 28.9% when one third of state legislators were women. Rankings: 13th of 50 Senate: 8 of 30 (26.7%) are women % Oregon Legislature Women 40% House: 18 of 60 (30%) are women 30% Method of election: Single-member districts 20% OR Local 10% USA Two of Oregon’s five largest cities with elected 0% mayors have female mayors: Eugene and Salem. -

Oregon Women Judges

Oregon Women Judges Table 2: Appointment v. Election Appointment / Election # of Appoint. Judges Term 1923-27 Gov. Walter M. Pierce 1 Spurlin 1959-67 Gov. Mark Hatfield 1 Lewis 1967-75 Gov. Tom McCall 4 Deiz, Frye, Schlegel, Field 1975-79 Gov. Robert W. Straub 3 Betty Roberts (Appeals), Frankel, Welch 1979-87 Gov. Victor G. Atiyeh 6 Bergman, Smith, Betty Roberts (Supreme), LaMar, Seitz, Deits Campbell, Graber, Aiken (District Ct.), Bergman, Welch, Rosenblum 1987-91 Gov. Neil Goldschmidt 11 (District Ct.), Haslinger, Graber (Appeals), Rhodes, Osborne, Johnson Wilson, Gayle Nachtigal, Anna Brown (District Ct.), Welch, Leeson, Abernethy, Aiken (Circuit Ct.), Rosenblum (Circuit Ct.), Wilson, Carlson, 1991-95 Gov. Barbara Roberts 20 Rhoades, Frantz, Souther Wyatt, Leggert, Brady, Anna Brown (Circuit Ct.), Kurshner, Brownhill, Orf, Bechtold 1995-2003: Frantz, Darling, Henry, Miller, Crain, Holcomb, Linder, Knieps, Leeson, Bearden, Bispham, Svetkey, Patricia A. Sullivan, 1995-2003; Waller, McKnight, Thompson, Tennyson, Fuchs, Maurer // Gov. John Kitzhaber 36 2011-15 2011-15: Hadlock, Wipper, Novotny, Mooney, Love, Holmes-Hein, Allen, Karabeika, Rigmaiden, Ravassipour, Martwick, Lagesen, Simmons, Pellegrini, Beth Roberts, Ostrye, Flynn Lindi Baker, Ortega, James, Burton, Jones, Dailey, Rosenblum (Appeals), Nelson, Cobb, You, Walters, Stuart, You, Trevino, Grant, 2003-2011 Gov. Ted Kulongoski 32 Beaman, Steele, Bachart, Prall, Easterday, Burge, Immergut, Skye, Duncan, Weber, Chanti, Rooke-Ley, Villa-Smith, Hillman, Hampton, Nakamoto (Appeals), Temple 2015- Gov. Kate Brown 5 McIntyre, Nakamoto (Supreme), Janney, Flint, Bottomly 119 Total Appointed by Governors Judges who Moved from Dorothy Baker, Campbell, Haslinger, Osborne, Holland, Carlson, District Court to Circuit Court 14 Wyatt, Leggert, Kurshner, Orf, Bechtold, Darling, Henry, Maurer with 1998 Consolidation Judges who were Elected to Deiz (Circuit Ct.), Kathleen Nachtigal, Dorothy Baker (Dist. -

Kathy Kleeman for Immediate Release (848) 932-8717 with Addition Of

Center for American Women and Politics www.cawp.rutgers.edu Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey [email protected] 191 Ryders Lane 848-932-9384 New Brunswick, New Jersey 08901-8557 Fax: 732-932-6778 February 13, 2015 Contact: Kathy Kleeman For immediate release (848) 932-8717 With Addition of Brown in Oregon, Women Governors Now Total Six When Oregon Secretary of State Kate Brown succeeds the resigning Governor John Kitzhaber on Wednesday, February 18, she will join five other women as chief executives in the states for a total of three Democrats and three Republicans. The Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP), a unit of the Eagleton Institute of Politics at Rutgers University, also reports that Brown will be Oregon’s second woman governor, following in the footsteps of Barbara Roberts, who served from 1991-95. She will be the 37th woman governor overall, and the 22nd Democratic woman, to lead a state’s government. Brown will be the seventh woman and the first Democratic woman to succeed a governor who resigned. One woman, Rose Mofford (D-AZ) took office after the governor was impeached. Of the women who were elected to states’ number two posts and then succeeded to the governorship, three were later elected in their own right to full gubernatorial terms. CAWP’s website has additional information about the history of women governors, women in statewide elective executive posts, and women in elective offices in Oregon. Additional general information about governors is available on the website of Eagleton’s Center on the American Governor.