Bob Packwood Oral History About Bob Dole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Richard Russell, the Senate Armed Services Committee & Oversight of America’S Defense, 1955-1968

BALANCING CONSENSUS, CONSENT, AND COMPETENCE: RICHARD RUSSELL, THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE & OVERSIGHT OF AMERICA’S DEFENSE, 1955-1968 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Joshua E. Klimas, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor David Stebenne, Advisor Professor John Guilmartin Advisor Professor James Bartholomew History Graduate Program ABSTRACT This study examines Congress’s role in defense policy-making between 1955 and 1968, with particular focus on the Senate Armed Services Committee (SASC), its most prominent and influential members, and the evolving defense authorization process. The consensus view holds that, between World War II and the drawdown of the Vietnam War, the defense oversight committees showed acute deference to Defense Department legislative and budget requests. At the same time, they enforced closed oversight procedures that effectively blocked less “pro-defense” members from influencing the policy-making process. Although true at an aggregate level, this understanding is incomplete. It ignores the significant evolution to Armed Services Committee oversight practices that began in the latter half of 1950s, and it fails to adequately explore the motivations of the few members who decisively shaped the process. SASC chairman Richard Russell (D-GA) dominated Senate deliberations on defense policy. Relying only on input from a few key colleagues – particularly his protégé and eventual successor, John Stennis (D-MS) – Russell for the better part of two decades decided almost in isolation how the Senate would act to oversee the nation’s defense. -

Senate Republican Conference John Thune

HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE JOHN THUNE 115th Congress Revised January 2017 HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE Table of Contents Preface ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1 Rules of the Senate Republican Conference ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....2 A Service as Chairman or Ranking Minority Member ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 B Standing Committee Chair/Ranking Member Term Limits ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 C Limitations on Number of Chairmanships/ Ranking Memberships ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 D Indictment or Conviction of Committee Chair/Ranking Member ....... ....... ....... .......5 ....... E Seniority ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... 5....... ....... ....... ...... F Bumping Rights ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 G Limitation on Committee Service ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ...5 H Assignments of Newly Elected Senators ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 Supplement to the Republican Conference Rules ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 6 Waiver of seniority rights ..... -

New Congress on Line to Be Next Big Brother

New Congress on Line to be Next Big Brother By Bill Hobby Hooray for the new Congress. They promised to take government off our back, and they've put it in our living room. They promised to free us from regulation, and they've concocted one that can deprive some unwitting computer nerds of their liberty. The amendment attached to an overhaul of federal communications law by the Senate Commerce Committee sets fines up to $100,000 and jail terms of up to two years for anyone who transmits material that is "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent" over the Internet. Welcome, thought police. As one columnist, Charles Levendosky of the Casper (Wyoming) Star-Tribune, put it, "It would melt the promise of this electronic Gutenberg." Many of us are just now discovering the wonders of cyberspace as presented through the Internet. We're just learning to pull up reproductions of paintings in the Louvre, reference material from the Library of Congress, bills up for consideration in the Texas Legislature. We are travelers in a fantastic new world of knowledge and information. This wonderful worldwide network of computers can answer our questions in seconds, whether we want to know about ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics or what happened today in the O.J. Simpson trial So naturally our Big Brothers in Congress couldn't leave us alone. Under the guise of protecting children from smut, the Senate has adopted one of the most draconian invasions of privacy ever. It has never been clear to me why the government considers that it owns the airwaves. -

Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986

Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Steven T. Wills June 2012 © 2012 Steven T. Wills. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwtaer Nichols Act of 1986 by STEVEN T. WILLS has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Ingo Traushweizer Assistant Professor of History Howard Dewald Interim Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT WILLS, STEVEN T., M.A., June 2012, History Navy and Marine Corps Opposition to the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 Director of Thesis: Ingo Traushweizer The Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 was the most comprehensive defense reorganization legislation in a generation. It has governed the way the United States has organized, planned, and conducted military operations for the last twenty five years. It passed the Senate and House of Representatives with margins of victory reserved for birthday and holiday resolutions. It is praised throughout the U.S. defense establishment as a universal good. Despite this, it engendered a strong opposition movement organized primarily by Navy Secretary John F. Lehman but also included members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, prominent Senators and Congressman, and President Reagan's Secretary of Defense Casper Weinberger. This essay will examine the forty year background of defense reform movements leading to the Goldwater Nichols Act, the fight from 1982 to 1986 by supporters and opponents of the proposed legislation and its twenty-five year legacy that may not be as positive as the claims made by the Department of Defense suggest. -

116Th Congress 15

ARKANSAS 116th Congress 15 ARKANSAS (Population 2010, 2,915,918) SENATORS JOHN NICHOLS BOOZMAN, Republican, of Rogers, AR; born in Shreveport, LA, Decem- ber 10, 1950; education: Southern College of Optometry, Memphis, TN, 1977; also attended University of Arkansas, Fayetteville, AR; professional: doctor of optometry; business owner; rancher; religion: Southern Baptist; married: Cathy Boozman; children: three daughters; commit- tees: Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry; Appropriations; Environment and Public Works; Vet- erans’ Affairs; elected to the U.S. House of Representatives 2001–11; elected to the U.S. Senate on November 2, 2010; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings https://boozman.senate.gov https://facebook.com/JohnBoozman twitter: @JohnBoozman 141 Hart Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 ...................................................... (202) 224–4843 Chief of Staff.—Toni-Marie Higgins. Deputy Chief of Staff /Counsel.—Susan Olson. Legislative Director.—Mackensie Burt. Communications Director.—Sara Lasure. Scheduler.—Holly Lewis. Senior Communications Advisor.—Patrick Creamer. 106 West Main Street, Suite 104, El Dorado, AR 71730 ........................................................ 870–863–4641 1120 Garrison Avenue, Suite 2B, Fort Smith, AR 72901 ....................................................... 479–573–0189 Constituent Services Director.—Kathy Watson. 300 South Church Street, Suite 400, Jonesboro, AR 72401 .................................................... 870–268–6925 1401 West Capitol -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

A History of the US Senate Republican Policy

03 39-400 Chro 7/8/97 2:34 PM Page ix Chronology TH CONGRESS 79 (1945–1947) Senate Republicans: 38; Democrats: 57 Republican Minority Leader: Wallace H. White, Jr. Republican Policy Committee Chairman: Robert Taft Legislative Reorganization Act proposes creating Policy Committees; House objects Senate Policy Committees established in Legislative Appropriations Act Republicans win majorities in both the Senate and House, 1946 Senate Policy Committee holds first meeting (December 31, 1946) TH CONGRESS Sen.White (R–ME). 80 (1947–1949) Senate Republicans: 51 (gain of 13); Democrats: 45 Republican Majority Leader: Kenneth S. Wherry Republican Policy Committee Chairman: Robert Taft Republican Policy Committee begins keeping a “Record Vote Analysis” of Senate votes Harry Truman reelected President, 1948 ST CONGRESS 81 (1949–1951) Senate Republicans: 42 (loss of 9, loss of majority); Democrats: 54 Republican Minority Leader: Kenneth S. Wherry Republican Policy Committee Chairman: Robert Taft Sen.Vandenberg (R–MI), President Truman, Sen. Connally (D–TX), and Secretary of State Byrnes. Sen.Taft (R–OH). Sen.Wherry (R–NE). ix 03 39-400 Chro 7/8/97 2:34 PM Page x ND CONGRESS 82 (1951–1953) Senate Republicans: 47 (gain of 5); Democrats: 49 Republican Minority Leader: Kenneth S. Wherry Republican Policy Committee Chairman: Robert Taft Kenneth Wherry dies (November 29, 1951); Styles Bridges elected Minority Leader Robert Taft loses the Republican presidential nomination to General Dwight Eisenhower Dwight Eisenhower elected President, Republicans win majorities in Senate and House, 1952 RD CONGRESS 83 (1953–1955) Senate Republicans: 48 (gain of 1); Democrats: 47; Independent: 1 Republican Majority Leader: Robert Taft Republican Policy Committee Chairman: William Knowland Robert Taft dies (July 31, 1953); William Knowland elected Majority Leader Homer Ferguson elected chairman of the Policy Committee TH CONGRESS 84 Sen. -

Primaries - Texas - PFC Press Releases (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 39, folder “Primaries - Texas - PFC Press Releases (1)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 39 of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NEWS RELEASE from the President Ford Committee P.O. BOX 15345, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78761 (512) 459-4101 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ' \- I AUSTIN---Senator John Tower will campaign on behalf of the 11 Four-for-Ford11 delegate teams during a non-stop tour into 20 Texas communities starting April 21. Tower, President Ford•s statewide chairman, will be urging Republican primary voters to elect the delegates pledged to Ford who will appear on the . May 1 ballot. A total of 96 delegates - 4 in each of Texas• 24 congressional districts -will be chosen. (Another 4 at-large delegates will be selected by the convention process) . ... 1 am looking forward to visiting with my constituents in behalf of . -

115Th Congress 219

OREGON 115th Congress 219 OREGON (Population 2010, 3,831,074) SENATORS RON WYDEN, Democrat, of Portland, OR; born in Wichita, KS, May 3, 1949; education: graduated from Palo Alto High School, 1967; B.A. in political science, with distinction, Stan- ford University, 1971; J.D., University of Oregon Law School, 1974; professional: attorney; member, American Bar Association; former director, Oregon Legal Services for the Elderly; former public member, Oregon State Board of Examiners of Nursing Home Administrators; co- founder and codirector, Oregon Gray Panthers, 1974–80; married: Nancy Bass Wyden; children: Adam David, Lilly Anne, Ava Rose, William Peter, and Scarlett Willa; committees: ranking member, Finance; Budget; Energy and Natural Resources; Joint Committee on Taxation; Select Committee on Intelligence; elected to the 97th Congress, November 4, 1980; reelected to each succeeding Congress; elected to the U.S. Senate on February 6, 1996, to fill the unexpired term of Senator Bob Packwood; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://wyden.senate.gov https://twitter.com/ronwyden 221 Dirksen Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–5244 Chief of Staff.—Jeff Michels. FAX: 228–2717 Legislative Director.—Isaiah Akin. Director of Scheduling.—Montana Judd. 911 Northeast 11th Avenue, Suite 630, Portland, OR 97232 ................................................... (503) 326–7525 405 East Eighth Avenue, Suite 2020, Eugene, OR 97401 ........................................................ (541) 431–0229 The Federal Courthouse, 310 West Sixth Street, Room 118, Medford, OR 97501 ................. (541) 858–5122 The Jamison Building, 131 Northwest Hawthorne Avenue, Suite 107, Bend, OR 97701 ...... (541) 330–9142 SAC Annex Building, 105 Fir Street, Suite 201, LaGrande, OR 97850 ................................. -

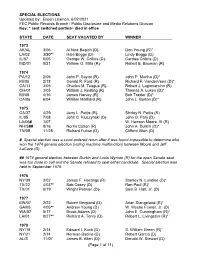

Special Election Dates

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

AP® Government and Politics: United States Balance of Power Between Congress and the President

PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT AP® Government and Politics: United States Balance of Power Between Congress and the President Special Focus The College Board: Connecting Students to College Success The College Board is a not-for-profit membership association whose mission is to connect students to college success and opportunity. Founded in 1900, the association is composed of more than 5,400 schools, colleges, universities, and other educational organizations. Each year, the College Board serves seven million students and their parents, 23,000 high schools, and 3,500 colleges through major programs and services in college admissions, guidance, assessment, financial aid, enrollment, and teaching and learning. Among its best-known programs are the SAT®, the PSAT/NMSQT®, and the Advanced Placement Program® (AP®). The College Board is committed to the principles of excellence and equity, and that commitment is embodied in all of its programs, services, activities, and concerns. For further information, visit www.collegeboard.com. The College Board acknowledges all the third-party content that has been included in these materials and respects the intellectual property rights of others. If we have incorrectly attributed a source or overlooked a publisher, please contact us. © 2008 The College Board. All rights reserved. College Board, Advanced Placement Program, AP, AP Vertical Teams, connect to college success, Pre-AP, SAT, and the acorn logo are registered trademarks of the College Board. PSAT/NMSQT is a registered trademark of the College Board and National Merit Scholarship Corporation. All other products and services may be trademarks of their respective owners. Visit the College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.com.