Calendar No. 183

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix File Anes 1988‐1992 Merged Senate File

Version 03 Codebook ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE ANES 1988‐1992 MERGED SENATE FILE USER NOTE: Much of his file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As a result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. MASTER CODES: The following master codes follow in this order: PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE CAMPAIGN ISSUES MASTER CODES CONGRESSIONAL LEADERSHIP CODE ELECTIVE OFFICE CODE RELIGIOUS PREFERENCE MASTER CODE SENATOR NAMES CODES CAMPAIGN MANAGERS AND POLLSTERS CAMPAIGN CONTENT CODES HOUSE CANDIDATES CANDIDATE CODES >> VII. MASTER CODES ‐ Survey Variables >> VII.A. Party/Candidate ('Likes/Dislikes') ? PARTY‐CANDIDATE MASTER CODE PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PEOPLE WITHIN PARTY 0001 Johnson 0002 Kennedy, John; JFK 0003 Kennedy, Robert; RFK 0004 Kennedy, Edward; "Ted" 0005 Kennedy, NA which 0006 Truman 0007 Roosevelt; "FDR" 0008 McGovern 0009 Carter 0010 Mondale 0011 McCarthy, Eugene 0012 Humphrey 0013 Muskie 0014 Dukakis, Michael 0015 Wallace 0016 Jackson, Jesse 0017 Clinton, Bill 0031 Eisenhower; Ike 0032 Nixon 0034 Rockefeller 0035 Reagan 0036 Ford 0037 Bush 0038 Connally 0039 Kissinger 0040 McCarthy, Joseph 0041 Buchanan, Pat 0051 Other national party figures (Senators, Congressman, etc.) 0052 Local party figures (city, state, etc.) 0053 Good/Young/Experienced leaders; like whole ticket 0054 Bad/Old/Inexperienced leaders; dislike whole ticket 0055 Reference to vice‐presidential candidate ? Make 0097 Other people within party reasons Card PARTY ONLY ‐‐ PARTY CHARACTERISTICS 0101 Traditional Democratic voter: always been a Democrat; just a Democrat; never been a Republican; just couldn't vote Republican 0102 Traditional Republican voter: always been a Republican; just a Republican; never been a Democrat; just couldn't vote Democratic 0111 Positive, personal, affective terms applied to party‐‐good/nice people; patriotic; etc. -

Senate Republican Conference John Thune

HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE JOHN THUNE 115th Congress Revised January 2017 HISTORY, RULES & PRECEDENTS of the SENATE REPUBLICAN CONFERENCE Table of Contents Preface ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 1 Rules of the Senate Republican Conference ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....2 A Service as Chairman or Ranking Minority Member ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 B Standing Committee Chair/Ranking Member Term Limits ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 C Limitations on Number of Chairmanships/ Ranking Memberships ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 4 D Indictment or Conviction of Committee Chair/Ranking Member ....... ....... ....... .......5 ....... E Seniority ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... 5....... ....... ....... ...... F Bumping Rights ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 G Limitation on Committee Service ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ....... ...5 H Assignments of Newly Elected Senators ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 5 Supplement to the Republican Conference Rules ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... ...... 6 Waiver of seniority rights ..... -

New Congress on Line to Be Next Big Brother

New Congress on Line to be Next Big Brother By Bill Hobby Hooray for the new Congress. They promised to take government off our back, and they've put it in our living room. They promised to free us from regulation, and they've concocted one that can deprive some unwitting computer nerds of their liberty. The amendment attached to an overhaul of federal communications law by the Senate Commerce Committee sets fines up to $100,000 and jail terms of up to two years for anyone who transmits material that is "obscene, lewd, lascivious, filthy or indecent" over the Internet. Welcome, thought police. As one columnist, Charles Levendosky of the Casper (Wyoming) Star-Tribune, put it, "It would melt the promise of this electronic Gutenberg." Many of us are just now discovering the wonders of cyberspace as presented through the Internet. We're just learning to pull up reproductions of paintings in the Louvre, reference material from the Library of Congress, bills up for consideration in the Texas Legislature. We are travelers in a fantastic new world of knowledge and information. This wonderful worldwide network of computers can answer our questions in seconds, whether we want to know about ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics or what happened today in the O.J. Simpson trial So naturally our Big Brothers in Congress couldn't leave us alone. Under the guise of protecting children from smut, the Senate has adopted one of the most draconian invasions of privacy ever. It has never been clear to me why the government considers that it owns the airwaves. -

Bob Packwood Oral History About Bob Dole

This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. http://dolearchives.ku.edu ROBERT J. DOLE ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Interview with Sen. BOB PACKWOOD July 20, 2007 Interviewer Richard Norton Smith Robert J. Dole Institute of Politics 2350 Petefish Drive Lawrence, KS 66045 Phone: (785) 864-4900 Fax: (785) 864-1414 This document is from the collections at the Dole Archives, University of Kansas. http://dolearchives.ku.edu Packwood–07-20–07–p. 2 [Sen. Packwood reviewed this transcript for accuracy of names and dates. Because no changes of substance were made, it is an accurate rendition of the original recording.] Smith: But at his insistence, it’s about more than Senator Dole, and, when we’re done, we hope we’ll have a mosaic that will really amount almost to a history of the modern Senate, and, in a still larger sense, of the political process as it has evolved since Bob Dole came to this town in 1961, for better or worse; and that’s a debatable point. Let me begin by something Senator [John W.] Warner said in yesterday’s [Washington] Post. It was interesting; I think he came to the Senate in ’78. Packwood: Yes. Smith: What year did you Packwood: I was elected in ’68; came in ’69. Smith: Okay. He talked aboutit’s interesting. He talked about, in effect, the good old days as he remembered them, when freshmen were seen but not heard, when you waited until your second year to give your maiden speech, and when you had a handler to sort of guide you through the initiation. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

Aclu Ar Covers R.Qxd

The Annual Update of the ACLU’s Nationwide Work on LGBT Rights and HIV/AIDS WhoWho We We Are Are 2005 2005 The Annual Update of the ACLU’s Nationwide Work on LGBT Rights and HIV/AIDS WHO WE ARE 2005 PARADOX, PROGRESS & SO ON . .1 FREEDOM RIDE: THE STORY OF TAKIA AND JO . .5 RELATIONSHIPS DOCKET . .7 WHAT MAKES A PARENT . .19 PARENTING DOCKET . .21 THE QUEER GUY AT HUNT HIGH . .25 YOUTH & SCHOOLS DOCKET . .27 LIFE’S CRUEL CHALLENGES . .31 DISCRIMINATION DOCKET . .33 TRANSLATINAS AND THE FIGHT FOR DERECHOS CIVILES . .37 TRANSGENDER DOCKET . .41 THE HARD TRUTH ABOUT SMALL TOWN PREJUDICE . .43 HIV/AIDS DOCKET . .45 HOW THE ACLU WORKS . .47 PROJECT STAFF . .49 COOPERATING ATTORNEYS . .51 CONTRIBUTORS . .53 Design: Carol Grobe Design 125 Broad Street, 18th Floor New York, NY 10004-2400 212.549.2627 [email protected] www.aclu.org Paradox, Progress & So On BY MATT COLES, PROJECT DIRECTOR The LGBT movement is at a pivotal moment in its sexual orientation. But just after the year ended, the a remarkable pace, none history. 2004 was a year of both remarkable progress U.S. Supreme Court let stand a lower court ruling of our recent gains is and stunning setbacks. For the first time, same-sex upholding Florida’s ban on adoption. And legislators in secure and continued couples were married in the United States – in Arkansas are already trying to undo the Little Rock progress is not assured. Massachusetts, San Francisco, Portland, Oregon, and judge’s decision. There are two forces at New Paltz, New York. -

115Th Congress 219

OREGON 115th Congress 219 OREGON (Population 2010, 3,831,074) SENATORS RON WYDEN, Democrat, of Portland, OR; born in Wichita, KS, May 3, 1949; education: graduated from Palo Alto High School, 1967; B.A. in political science, with distinction, Stan- ford University, 1971; J.D., University of Oregon Law School, 1974; professional: attorney; member, American Bar Association; former director, Oregon Legal Services for the Elderly; former public member, Oregon State Board of Examiners of Nursing Home Administrators; co- founder and codirector, Oregon Gray Panthers, 1974–80; married: Nancy Bass Wyden; children: Adam David, Lilly Anne, Ava Rose, William Peter, and Scarlett Willa; committees: ranking member, Finance; Budget; Energy and Natural Resources; Joint Committee on Taxation; Select Committee on Intelligence; elected to the 97th Congress, November 4, 1980; reelected to each succeeding Congress; elected to the U.S. Senate on February 6, 1996, to fill the unexpired term of Senator Bob Packwood; reelected to each succeeding Senate term. Office Listings http://wyden.senate.gov https://twitter.com/ronwyden 221 Dirksen Senate Office Building, Washington, DC 20510 .................................................. (202) 224–5244 Chief of Staff.—Jeff Michels. FAX: 228–2717 Legislative Director.—Isaiah Akin. Director of Scheduling.—Montana Judd. 911 Northeast 11th Avenue, Suite 630, Portland, OR 97232 ................................................... (503) 326–7525 405 East Eighth Avenue, Suite 2020, Eugene, OR 97401 ........................................................ (541) 431–0229 The Federal Courthouse, 310 West Sixth Street, Room 118, Medford, OR 97501 ................. (541) 858–5122 The Jamison Building, 131 Northwest Hawthorne Avenue, Suite 107, Bend, OR 97701 ...... (541) 330–9142 SAC Annex Building, 105 Fir Street, Suite 201, LaGrande, OR 97850 ................................. -

Special Election Dates

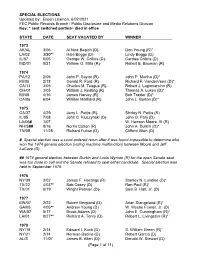

SPECIAL ELECTIONS Updated by: Eileen Leamon, 6/02/2021 FEC Public Records Branch / Public Disclosure and Media Relations Division Key: * seat switched parties/- died in office STATE DATE SEAT VACATED BY WINNER 1973 AK/AL 3/06 Al Nick Begich (D)- Don Young (R)* LA/02 3/20** Hale Boggs (D)- Lindy Boggs (D) IL/07 6/05 George W. Collins (D)- Cardiss Collins (D) MD/01 8/21 William O. Mills (R)- Robert E. Bauman (R) 1974 PA/12 2/05 John P. Saylor (R)- John P. Murtha (D)* MI/05 2/18 Gerald R. Ford (R) Richard F. VanderVeen (D)* CA/13 3/05 Charles M. Teague (R)- Robert J. Lagomarsino (R) OH/01 3/05 William J. Keating (R) Thomas A. Luken (D)* MI/08 4/16 James Harvey (R) Bob Traxler (D)* CA/06 6/04 William Mailliard (R) John L. Burton (D)* 1975 CA/37 4/29 Jerry L. Pettis (R)- Shirley N. Pettis (R) IL/05 7/08 John C. Kluczynski (D)- John G. Fary (D) LA/06# 1/07 W. Henson Moore, III (R) NH/S## 9/16 Norris Cotton (R) John A. Durkin (D)* TN/05 11/25 Richard Fulton (D) Clifford Allen (D) # Special election was a court-ordered rerun after it was found impossible to determine who won the 1974 general election (voting machine malfunction) between Moore and Jeff LaCaze (D). ## 1974 general election between Durkin and Louis Wyman (R) for the open Senate seat was too close to call and the Senate refused to seat either candidate. Special election was held in September 1975. -

HELEN NICKUM INTERVIEW Tape 1, Side 1 GK

! HELEN NICKUM INTERVIEW ! !Tape 1, Side 1 GK: My name is Greg Karnes, and today’s date is January 28th, 2011. I am interviewing Helen Nickum. I guess we’ll get started. If you could state your full ! name and where and when you were born. Helen My full name is Helen Nickum, no middle name. I was born on February 4th, ! 1928, in Portland, Oregon. !GK: I guess a good place to start out is to sort of get a sense of your family history. Helen Yes, it goes back to about 1756, a far piece, when a father and three sons immigrated from Erzweiler, Germany down the Rhine River to a port in the Netherlands to board a ship to America in answer to an ad put in the paper by William Penn. And they landed in Philadelphia or near Philadelphia through several different clerks, and the name was spelled differently by the clerks because none of the group knew how to write and the genealogy came out with ! several spellings. So, that’s where my father’s family started. Both my mother and father’s folks lived in--were raised in Pennsylvania. My father’s folks came across the prairie from Baltimore to Corinne, Utah, where is-- near the place where the Golden Spike was planted when the railroads met. They ran a hotel there, which was the only brick building in town and a haven for when the Indians were uprising. Some of the chairs from that hotel are still in the ! town library. !GK: What were their names? Helen Nickum, John Nickum, that was my father’s father, and his mother, Cornelia Allen, had come by railroad from Baltimore, she leaving her husband because he was an alcoholic. -

The Rise and Fall of “No Special Rights”

Courtesy of the Rural Organizing Project The Rise and Fall of “No Special Rights” WILLIAM SCHULTZ THE OREGONIAN, the largest newspaper in the state, delivered a bracing message to readers from its editorial page the morning of October 11, 1992: “Oregon faces a clear and present danger of becoming the first state since the Civil War to withdraw civil rights instead of adding to them.” The editorial warned that Oregon’s ballot would include a “ghastly gospel” promoted by “would-be ayatollahs.” The official name for this “ghastly gospel” was Mea- sure 9, and the “ayatollahs” were its sponsors, the Oregon Citizens Alliance (OCA).1 As it appeared on the Oregon ballot, Measure 9 asked voters: “Shall THE COLUMBIA COUNTY CITIZENS FOR HUMAN DIGNITY group of Oregon formed in [the state] Constitution be amended to require that all governments discourage 1992 in response to Oregon Measure 9, a campaign to amend the Oregon Constitution to require homosexuality, other listed ‘behaviors,’ and not facilitate or recognize them?” discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Members of the group are pictured here marching The “other behaviors” mentioned by the measure were “pedophilia, sadism, in protest of the measure. or masochism.”2 It was one of the most comprehensive — and harshest — anti- gay measures put to voters in American history. The editors of the Oregonian were so concerned about the possibility of the measure’s passage that they did not limit their denunciation to a single editorial. The paper ran an eleven-part The amendment was sponsored by the Colorado analogue of OCA, Colorado series condemning the measure, with each entry titled “Oregon’s Inquisition.” for Family Values (CFV). -

Port Orford Today! FREE! Port Orford’S BEST NEWSPAPER! Vol

Port Orford Today! FREE! Port Orford’s BEST NEWSPAPER! Vol. 11 Number 40 Thursday, October 19, 2000 20002000 © 2000 by The Downtown Fun Zone The Downtown Fun Zone Valerie: . [email protected] Evan & Valerie Kramer, Owners Evan: [email protected] Impartial Voters Guides 832 Highway 101, P.O. Box 49 Brenda: [email protected] Now Available at the Library Port Orford, OR 97465 Nancy:... [email protected] and at Rays Place Market (541) 332-6565 (Voice or FAX) http://www.harborside.com/~funzone Candidate Forum a ranch and tree farm since 1972. He publicly apologizing to Ava Peterson by Evan Kramer spoke of the importance of family wage over a vehicle accident. DiRusso said he jobs. He said we have two Oregon’s now. had been the county emergency services Nine candidates for The one in Portland which he said was coordinator for one year and served on various offices ap- prospering and the rural one which he the Ophir Fire board. He said he was peared at the League said was not. looking for the young vote. of Women Voters Candidate Forum in Curry County Commissioner candidate Curry County Commissioner for position Port Orford on Thurs- for position #2 Marlyn Schafer (R) asked #3 candidate Lucie LaBonte (D) said the day night before a the question “why vote for me.” She said county has had to use up the carryover large gathering of the she knows how to get things done. She contingency funds and had to borrow public. spoke of the importance of public safety $700,000 from the road department. -

Oregon English CE

Date Printed: 06/16/2009 JTS Box Number: lFES 76 Tab Number: 38 Document Title: Voters pamphlet Document Date: 1986 Document Country: United States -- Oregon Document Language: English lFES 10: CE02451 I- .. STATE OF OREGON PRIMARY ELECTION MAY 20. 1986 Compiled and Distributed by £3.k., ~ Secretary of State This Voter's Pamphlet is the personal property of the recipient elector for assistance at the Polls. Dear Voter: On May 20th, Oregonians will participate in our Primary Election as they have done for decades, , Oregon has been a leader in the nation with laws to encourage voter participation and to pro- tect the integrity of our election system. First came the establishment of our voter registration system in 1899. Then, the first voter's pamphlet, in 1904, to help Oregonians understand when voting no meant no and when voting no meant yes! The initiative petition, that we now take for granted, was considered progressive in 1902. In fact, Oregon was the first state in the nation to use the initiative petition. We were the first state to allow for the direct election of our U.S. Senators by the people, in 1906, rather than the Legislative Assembly. The "Oregon System", a controversial law adopted by the legislature , in 1908, allowed for the recall of publicly elected officials. The newly created law was put into action in 1909 with the recall of the mayor of Junction City. In 1910, we became the first state to have a presidential preference Primary Election. The theme of this year's voter's pamphlet highlights some of these and other Oregon Firsts.