The Naming of Moscows in the USA

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 21, 2012 at 3:30 PM Land Use Department SCHOOL FOR

" , **SECOND AMENDED** BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT Tuesday, August 21,2012 at 6:00 P.M. (Note New Time) 200 Lincoln Ave. Santa Fe NM City Council Chambers Field Trip - August 21, 2012 at 3:30 P.M. Land Use Department SCHOOL FOR ADVANCED RESEARCH 660 GARCIA STREET Meet at Reception (main building on left) A. ROLL CALL B. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE C. APPROVAL OF AGENDA D. APPROVAL OF MINUTES: July 17, 2012 minutes E. FINDINGS/CONCLUSIONS: Case #2012-41. 614 Acequia Madre Special Use Permit F. OLD BUSINESS G. NEW BUSINESS Case #2012-77. 341 Magdalena Street Variance Jennifer and Brent Cline, owners, request a variance to allow garage doors to be set back 8 feet from the front property lines where 20 feet is required. The property is 0.2± acres and is zoned R-21 (Residential, 21 dwelling units per acre). (Dan Esquibel, Case Manager) Case #2012-69. Holy Trinity Orthodox Church Special Use Permit. Holy Trinity Orthodox Church requests a Special Use Permit for dormitory boarding and monastery use. The property is zoned R-1 (Residential, one dwelling unit per acre) and is located at 207 East Cordova Road. (William Lamboy, Case Manager) Case #2012-71. School for Advanced Research Special Use Permit. JenkinsGavin Design and Development, agents for School for Advanced Research, request a Special Use Permit to aI/ow a museum use at 660 Garcia Street. The property is zoned R-2 (Residential, two dwelling units per acre) and R-3 (Residential, three dwelling units per acre). (William Lamboy, Case Manager) H. BUSINESS FROM THE FLOOR I. -

SCX-920-System-Controller.Pdf

Infinity SCX 920 System Controller The Infinity SCX 920 is a stand-alone, programmable, microprocessor-based system controller that F E A T U R E S is used for Direct Digital Control of chillers, cooling towers, boilers, air handling units, perimeter • Stand-alone DDC for System radiation, lighting, etc. The Infinet’s true peer-to-peer communication protocol provides the Infinity Reliability SCX 920 with the ability to instantly communicate with Infinity network controllers such as the CX • Peer-to-Peer Communications 9200, as well as the entire network of Andover Infinity controllers. Up to 254 SCX 920s can be Provide Transparent Data networked with the Infinity CX family of controllers. Transfer • Plain English® Language The SCX 920 comes standard with a metal cover plate suitable for panel mounting (shown). Simplifies Programming An optional enclosure is available for wall mounting. • Universal Inputs and Outputs for Flexible Control Configurations COMMUNICATIONS Communication to the Infinity SCX 920 is handled via the Infinet bus, a twisted pair, half duplex RS-485 interface. • Expandable I/O Meets Additional Communication is accomplished with a token passing protocol which provides full transparent data transfer between all Point Count Needs Infinity controllers on the network. • Detachable Input/Output INPUTS Connectors for Easy Installation The Infinity SCX 920 is capable of sensing sixteen inputs. Each input can accept a digital (on/off), counter (up to 4 Hz), voltage (0-10 VDC), or temperature signal. • Full Function Manual Overrides Provide Status Feedback OUTPUTS • Optional Display/Keypad for Local The Infinity SCX 920 has eight Universal outputs providing pulse, variable voltage (0 - 20 VDC), variable current, (0 - 20mA) Information Control or on/off control of motors and lighting with Form C relays. -

Byzantine Relations with Northern Peoples in the Tenth Century

CONSTANTINE PORPHYROGENITUS, DE ADMINISTRANDO IMPERIO Byzantine Relations with Northern Peoples in the Tenth Century INTRODUCTION Byzantine relations with Bulgaria were complicated in the early years of the tenth century: more complicated than many historians have allowed. The Bulgarian Tsar Symeon (c. 894-927) has been portrayed by both Byzantine and modern authors as an aggressor intent on capturing Constantinople from which he might rule a united Byzantine-Bulgarian empire. However, recent scholarship (notably the work of Bozhilov and Shepard) has questioned this, and maintained that Symeon's ambitions were more limited until the final years of his reign, the 920s, when he engineered a series of confrontations with the Byzantine Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (920- 44). (We will cover these years elsewhere: see the letters of Nicholas Mystikos and Theodore Daphnopates.) Symeon's died on 27 May 927, and his successor Peter (d. 967) immediately launched a major invasion of the Byzantine administrative district of Macedonia. As one of four sons such a show of strength would have been necessary to secure the support of his father's boyars. However, the Bulgarian troops withdrew swiftly, at the same time razing the fortresses that they had held until then in Thrace, and this early performance was not repeated. Instead, it heralded forty years of apparent harmony and cooperation between the two major powers in the northern Balkans. The reason for the withdrawal, and the centrepiece of the enduring Bulgarian Byzantine accord was the marriage in 927 of Peter to Maria Lecapena, granddaughter of the (senior) ruling emperor Romanus I Lecapenus.Peter has generally been held to have presided over the dramatic decline of Bulgaria. -

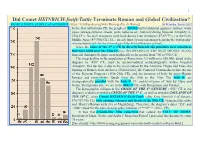

Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: G

1 Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demografia_di_Roma] G. Heinsohn, January 2021 In the first millennium CE, the people of ROME built residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc., but only during Imperial Antiquity (1- 230s CE). No such structures were built during Late Antiquity (4th-6th/7th c.) or the Early Middle Ages (8th-930s CE). [See already https://q-mag.org/gunnar-heinsohn-the-stratigraphy- of-rome-benchmark-for-the-chronology-of-the-first-millennium-ce.html] Since the ruins of the 3rd c. CE lie directly beneath the primitive new structures that were built after the 930s CE (i.e., BEGINNING OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES), Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from 700 to 930s CE. The steep decline in the population of Rome from 1.5 million to 650,000, dated in the diagram to "450" CE, must be accommodated archaeologically within Imperial Antiquity. This decline is due to the crisis caused by the Antonine Plague and Fires, the burning of Rome's State Archives (Tabularium), the Comet of Commodus before the rise of the Severan Emperors (190s-230s CE), and the invasion of Italy by proto-Hunnic Iazyges and proto-Gothic Quadi from the 160s to the 190s. The 160s ff. are stratigraphically parallel with the 450s ff. CE and its invasion of Italy by Huns and Goths. Stratigraphically, we are in the 860s ff. CE, with Hungarians and Vikings. The demographic collapse in the CRISIS OF THE 6th CENTURY (“553” CE in the diagram) is identical with the CRISIS OF THE 3rd C., as well as with the COLLAPSE OF THE 10th C., when Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle (after King Heinrich I of Saxony; 876/919-936 CE) with ensuing volcanos and floods of the 930s CE ) damaged the globe and Henry’s Roman style city of Magdeburg). -

1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King Athelstan’s Sisters and Frankish Queenship Simon MacLean (University of St Andrews) ‘The holy laws of kinship have purposed to take root among monarchs for this reason: that their tranquil spirit may bring the peace which peoples long for.’ Thus in the year 507 wrote Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths, to Clovis, king of the Franks.1 His appeal to the ideals of peace between kin was designed to avert hostilities between the Franks and the Visigoths, and drew meaning from the web of marital ties which bound together the royal dynasties of the early-sixth-century west. Theoderic himself sat at the centre of this web: he was married to Clovis’s sister, and his daughter was married to Alaric, king of the Visigoths.2 The present article is concerned with a much later period of European history, but the Ostrogothic ruler’s words nevertheless serve to introduce us to one of its central themes, namely the significance of marital alliances between dynasties. Unfortunately the tenth-century west, our present concern, had no Cassiodorus (the recorder of the king’s letter) to methodically enlighten the intricacies of its politics, but Theoderic’s sentiments were doubtless not unlike those that crossed the minds of the Anglo-Saxon and Frankish elite families who engineered an equally striking series of marital relationships among themselves just over 400 years later. In the early years of the tenth century several Anglo-Saxon royal women, all daughters of King Edward the Elder of Wessex (899-924) and sisters (or half-sisters) of his son King Athelstan (924-39), were despatched across the Channel as brides for Frankish and Saxon rulers and aristocrats. -

Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming

Y E L L O W S T O N E CENTER FOR RESOURCES 2006 ANNUAL REPORT Y E L L O W S T O N E CENTER FOR RESOURCES 2006 ANNUAL REPORT Yellowstone Center for Resources National Park Service Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming YCR–2007–03 Suggested citation: Yellowstone Center for Resources. 2007. Yellowstone Center for Resources Annual Report, 2006. National Park Service, Mammoth Hot Springs, Wyoming, YCR-2007-03. Photographs not otherwise marked are courtesy of the National Park Service. Cover photos: center, boreal toad at High Lake (NPS); clockwise from top, Matt Metz (foreground) and Rick McIntrye observe a wolf–wolf clash (NPS); a pygmy owl (Terry McEneaney); wagon and mules on Slough Creek (NPS); Nez Perce drummer at the 3rd annual Nez Perce pipe ceremony along the Firehole River (NPS). ii Contents Centaurea repens. Introduction ..................................................................iv Part I: Cultural Resource Programs Archeology .........................................................................1 Archives, Library, and Museum Collections .................3 Ethnography.......................................................................7 Historic Road Rehabilitation ...........................................9 Historic Structures ..........................................................11 Yellowstone History ........................................................12 Part II: Natural Resource Programs Air, Land, and Water .......................................................13 Aquatic Resources ...........................................................16 -

Cd Katalogue 99:1

FLAT NOZZLES FOR FIXED INSTALLATION REPLACE OPEN PIPE OF DIAMETERS: 3 - 6 mm 1/8” - 1/4” BENEFITS Reduces the noise level – 14 - 24 dB(A) Decreases air consumption – 15 - 55 % Safety nozzles – Meet OSHA standards Silvent 920 and 921 are flat nozzles designed to generate a ACCESSORY broad and efficient band of air. They are outstanding for use wherever a wide but thin striking surface is required. Flat noz- ADJUSTABLE SWIVEL JOINT zles are suitable for most areas of application, such as: drying, An adjustable swivel joint for set- transporting, cooling, cleaning etc. These nozzles are often used ting the direction of the air cone. in manifold systems, providing silent and highly efficient air The joint enables easy fine-tuning knives. The 920 and 921 are made of zinc. Their exhaust ports of the blowing angle without are protected from external forces by flanges. Both nozzles fully affecting other fixed equipment. Correct adjustment of the blowing comply with OSHA safety regulations. Patented. angle results in a lower noise level and increased efficiency. Additional information in tab: Accessories DIMENSIONS PRODUCT INFORMATION ORDER NO./MODEL 920A 920B 921 A mm 64 64 44 A B ” 2.52 2.52 1.73 mm 32 32 22 B ” 1.26 1.26 0.87 BSP 1/4” 1/4” 1/8” C* NPT 1/4”-18 1/8”-27 1/8”-27 C D mm 46.3 46.3 23.9 D ” 1.82 1.82 0.94 mm 14.3 14.3 11 E ” 0.56 0.56 0.43 mm 80 80 55 F ” 3.15 3.15 2.17 E 6.5(0.26") mm 6 6 4 Replaces open pipe ” 1/4 1/4 1/8 Nm3/h 30 30 17 4(0.16") Air consumption SCFM 17.7 17.7 9.7 F Sound level dB(A) 81 81 80 N 5.5 5.5 3.0 Blowing force Oz 19.4 19.4 10.6 °C -20/+70 -20/+70 -20/+70 Max. -

Directory of Commercial Testing and College Research Laboratories

DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF STANDARDS GEORGE K. BURGESS, Director DIRECTORY OF COMMERCIAL TESTING AND COLLEGE RESEARCH LABORATORIES MISCELLANEOUS PUBLICATION No. 90 BUREAU OF STANDARDS PAMPHLETS ON TESTING There are listed below a few of the official publications of the Bureau of Standards relating to certain phases of testing, including Scientific Papers (S), Technologic Papers (T), Circulars (C), and Miscellaneous Publications (M). Copies of the pamphlets can be obtained, at the prices stated, from the Superintendent of Documents, Government Printing Office, Washington, D. C. In ordering pamphlets from the Superintendent of Documents the bureau publication symbol and number must be stated, and the order must be accompanied by cash. Automobile-tire fabric testing, standardization of, Hose, garden, selection and care of C327. (In T68. Price, 10 cents. press.) Hydrogen sulphide in gas, lead acetate test for, T41. Bags, paper, for cement and lime, a study of test Price, 25 cents. methods for, T187. Price, 5 cents. Hydrometers, testing of, CI 6. Price, 5 cents. Barometers, the testing of, C46. Price, 10 cents. Inks, their composition, Beams, reinforced concrete, shear tests of, T314. manufacture, and methods of testing, C95. Price, 10 Price, 50 cents. cents. Inks, printing, the composition, properties, and test- Bricks, transverse test of, T251. Price, 10 cents. ing of, C53. Price, 10 cents. Bridge columns, large, tests of, T101. Price, 30 cents. Lamp life-testing equipment and methods, recent Cast steel, centrifugally, tests of, T192. Price, 10 developments in, T325. Price, 15 cents. cents. Lamps, incandescent, life testing of, S265. Price, Clay refractories, the testing of, with special refer- 10 cents. -

The Origins of the English Kingdom

ENGLISH KINGDOM The Origins of the English KINGDOMGeorge Molyneaux explores how the realm of the English was formed and asks why it eclipsed an earlier kingship of Britain. UKE WILLIAM of Normandy defeated King King Harold is Old English ones a rice – both words can be translated as Harold at Hastings in 1066 and conquered the killed. Detail ‘kingdom’. The second is that both in 1016 and in 1066 the from the Bayeux English kingdom. This was the second time in 50 Tapestry, late 11th kingdom continued as a political unit, despite the change years that the realm had succumbed to external century. in ruling dynasty. It did not fragment, lose its identity, or Dattack, the first being the Danish king Cnut’s conquest of become subsumed into the other territories of its conquer- 1016. Two points about these conquests are as important as ors. These observations prompt questions. What did this they are easily overlooked. The first is that contemporaries 11th-century English kingdom comprise? How had it come regarded Cnut and William as conquerors not merely of an into being? And how had it become sufficiently robust and expanse of land, but of what Latin texts call a regnum and coherent that it could endure repeated conquest? FEBRUARY 2016 HISTORY TODAY 41 ENGLISH KINGDOM Writers of the 11th century referred to the English kingdom in Latin as the regnum of ‘Anglia’, or, in the vernacular, as the rice of ‘Englaland’. It is clear that these words denoted a territory of broadly similar size and shape to what we think of as ‘England’, distinct from Wales and stretching from the Channel to somewhere north of York. -

The Canonization of Pope John XIII and Pope John Paul II -April 27, 2014 in Rome by Rev

The Canonization of Pope John XIII and Pope John Paul II -April 27, 2014 in Rome by Rev. Mr. Michael Conway 1.5 million. That's how many people came to Rome for the beatification of now Pope Saint John Paul II back in May of 2011. OFF!C"!Ul\I DE IJTIJRG!CIS CE1£BRATIONIRUS In a word, it was chaotic. Streets that were supposed to be closed SUl\11'11 l'Ot-rr!FICIS were open, streets that were supposed to be open were closed, you couldn't find a cab, the police had no idea what was going on, there weren't enough bathrooms, or food, or water ... it was a mess. So of course I couldn't wait to see what the canonization Mass would hold. Since I was, at long last, a deacon, I was holding out hope that I would be needed to do something ... This would be the perfect storm. Not only was it to be the canonization of John Paul II, whose biography is so well-known I scarcely need to give it here, but it was also to be the canonization of Pope John XXIII, whose memory has not faded in the hearts and minds of the Italian people. The icing on the cake is that it would Latin admission ticket for Deacon Michael Conway to the dual papal canonization be presided over by Pope Francis, who seemingly can't do anything ceremony, Rome. without catching the world's eye. (And, for good measure, Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI joined Pope Francis in the celebration, just Thousands of portable toilets were set up at key locations. -

Inventory Control Form

INVENTORY CONTROL FORM Patient Information: Synthes USA Products, LLC Synthes (Canada) Ltd. To order: (800) 523–0322 To order: (800) 668–1119 Date: Hospital: Surgeon: Procedure: Implants TFN–Advanced, Long Nails, 9 mm distal diameter, sterile TFN–Advanced, Long Nails, 10 mm distal diameter, sterile FEMORAL FEMORAL RIGHT LEFT LENGTH NECK ANGLE RIGHT LEFT LENGTH NECK ANGLE 04.037.916S 04.037.917S 260 125° 04.037.016S 04.037.017S 260 125° 04.037.918S 04.037.919S 280 125° 04.037.018S 04.037.019S 280 125° 04.037.920S 04.037.921S 300 125° 04.037.020S 04.037.021S 300 125° 04.037.922S 04.037.923S 320 125° 04.037.022S 04.037.023S 320 125° 04.037.924S 04.037.925S 340 125° 04.037.024S 04.037.025S 340 125° 04.037.926S 04.037.927S 360 125° 04.037.026S 04.037.027S 360 125° 04.037.928S 04.037.929S 380 125° 04.037.028S 04.037.029S 380 125° 04.037.930S 04.037.931S 400 125° 04.037.030S 04.037.031S 400 125° 04.037.932S 04.037.933S 420 125° 04.037.032S 04.037.033S 420 125° 04.037.934S 04.037.935S 440 125° 04.037.034S 04.037.035S 440 125° 04.037.936S 04.037.937S 460 125° 04.037.036S 04.037.037S 460 125° 04.037.938S 04.037.939S 480 125° 04.037.038S 04.037.039S 480 125° 04.037.946S 04.037.947S 260 130° 04.037.046S 04.037.047S 260 130° 04.037.948S 04.037.949S 280 130° 04.037.048S 04.037.049S 280 130° 04.037.950S 04.037.951S 300 130° 04.037.050S 04.037.051S 300 130° 04.037.952S 04.037.953S 320 130° 04.037.052S 04.037.053S 320 130° 04.037.954S 04.037.955S 340 130° 04.037.054S 04.037.055S 340 130° 04.037.956S 04.037.957S 360 130° 04.037.056S 04.037.057S 360 130° -

Abu Bakr Al-Razi

From the James Lind Library Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine; 106(9) 370–372 DOI: 10.1177/0141076813496515 Qualifying and quantifying medical uncertainty in 10th-century Baghdad: Abu Bakr al-Razi Peter E Pormann School of Arts, Histories and Cultures, University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK Corresponding author: Peter E Pormann. Email: [email protected] Introduction medicine moved to them, and some of the most highly regarded doctors looking after patients in the Abu Bakr Muhammad ibn Zakariya’ al-Razi (d. 925) upper echelons of society worked and taught in them. was one of the most interesting and innovative clin- In addition, given their large numbers of patients, icians of the medieval world.1 He distinguished small- hospitals provided an infrastructure for research. pox from measles, experimented on an ape to establish the toxicity of quicksilver (mercury) and Hospital records used a control group to assess whether bloodletting was an effective treatment for ‘brain fever’.2–5 Following Hippocrates’ example in recording cases, Al-Razi stated in one of his treatises: al-Razi stressed the fundamental importance of docu- menting the characteristics and treatment of hospital My aim and objective is [to provide] things useful to patients, and more than 2000 of these case-notes have people who practise and work, not for those engaged survived.8 In Doubts about Galen (Al-Shukuk ‘ala in research and theory5 (pp. 112–13). Jalinus), al-Razi referred to registers of hospital patients’ names and notes as a basis for criticising the Greek physician Galen of Pergamum (c.