Byzantine Relations with Northern Peoples in the Tenth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Naming of Moscows in the USA

Names, Vol. 37, No.1 (March 1989) The Naming of Moscows in the USA Irina Vasiliev Abstract Since 1800, at least forty-seven populated places in the United States have borne the name Moscow. The reasons for having been so named fall into four classes of placename type: commemorative, anticipatory, transfer, and mistake. The stories of these communities and their namings tell much about the growth of this country, the flow of in- formation within it, and each community's perception of itself. ***** The names Berlin, London; Moscow, and Paris evoke images of European sophistication and Old World charm. Here in the United States, these and other European and classical names have been applied as place names to communities that bear no resemblance to the original cities. We have all seen. them on our road maps: the Romes and the Petersburgs, the Viennas and Madrids. They have become commonplace to us. And there are many of each of them: not just one Rome, but thir- ty-five; not just one Cairo, but twenty-one. So the questions come up: Why were these communities named what they were? Who·were the people behind the naming? What were the reasons for the names they chose? It would be too large a task to examine all of the Old W orldnames that have been used across the United States in the last two hundred years. However, I have been able look at one name and determine the reasons for its widespread use. The name that I have chosen to look at is Moscow. -

Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Bulgaria, October 2006 COUNTRY PROFILE: BULGARIA October 2006 COUNTRY Formal Name: Republic of Bulgaria (Republika Bŭlgariya). Short Form: Bulgaria. Term for Citizens(s): Bulgarian(s). Capital: Sofia. Click to Enlarge Image Other Major Cities (in order of population): Plovdiv, Varna, Burgas, Ruse, Stara Zagora, Pleven, and Sliven. Independence: Bulgaria recognizes its independence day as September 22, 1908, when the Kingdom of Bulgaria declared its independence from the Ottoman Empire. Public Holidays: Bulgaria celebrates the following national holidays: New Year’s (January 1); National Day (March 3); Orthodox Easter (variable date in April or early May); Labor Day (May 1); St. George’s Day or Army Day (May 6); Education Day (May 24); Unification Day (September 6); Independence Day (September 22); Leaders of the Bulgarian Revival Day (November 1); and Christmas (December 24–26). Flag: The flag of Bulgaria has three equal horizontal stripes of white (top), green, and red. Click to Enlarge Image HISTORICAL BACKGROUND Early Settlement and Empire: According to archaeologists, present-day Bulgaria first attracted human settlement as early as the Neolithic Age, about 5000 B.C. The first known civilization in the region was that of the Thracians, whose culture reached a peak in the sixth century B.C. Because of disunity, in the ensuing centuries Thracian territory was occupied successively by the Greeks, Persians, Macedonians, and Romans. A Thracian kingdom still existed under the Roman Empire until the first century A.D., when Thrace was incorporated into the empire, and Serditsa was established as a trading center on the site of the modern Bulgarian capital, Sofia. -

Vladimir-Peter-Goss-The-Beginnings

Vladimir Peter Goss THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Published by Ibis grafika d.o.o. IV. Ravnice 25 Zagreb, Croatia Editor Krešimir Krnic This electronic edition is published in October 2020. This is PDF rendering of epub edition of the same book. ISBN 978-953-7997-97-7 VLADIMIR PETER GOSS THE BEGINNINGS OF CROATIAN ART Zagreb 2020 Contents Author’s Preface ........................................................................................V What is “Croatia”? Space, spirit, nature, culture ....................................1 Rome in Illyricum – the first historical “Pre-Croatian” landscape ...11 Creativity in Croatian Space ..................................................................35 Branimir’s Croatia ...................................................................................75 Zvonimir’s Croatia .................................................................................137 Interlude of the 12th c. and the Croatia of Herceg Koloman ............165 Et in Arcadia Ego ...................................................................................231 The catastrophe of Turkish conquest ..................................................263 Croatia Rediviva ....................................................................................269 Forest City ..............................................................................................277 Literature ................................................................................................303 List of Illustrations ................................................................................324 -

August 21, 2012 at 3:30 PM Land Use Department SCHOOL FOR

" , **SECOND AMENDED** BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT Tuesday, August 21,2012 at 6:00 P.M. (Note New Time) 200 Lincoln Ave. Santa Fe NM City Council Chambers Field Trip - August 21, 2012 at 3:30 P.M. Land Use Department SCHOOL FOR ADVANCED RESEARCH 660 GARCIA STREET Meet at Reception (main building on left) A. ROLL CALL B. PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE C. APPROVAL OF AGENDA D. APPROVAL OF MINUTES: July 17, 2012 minutes E. FINDINGS/CONCLUSIONS: Case #2012-41. 614 Acequia Madre Special Use Permit F. OLD BUSINESS G. NEW BUSINESS Case #2012-77. 341 Magdalena Street Variance Jennifer and Brent Cline, owners, request a variance to allow garage doors to be set back 8 feet from the front property lines where 20 feet is required. The property is 0.2± acres and is zoned R-21 (Residential, 21 dwelling units per acre). (Dan Esquibel, Case Manager) Case #2012-69. Holy Trinity Orthodox Church Special Use Permit. Holy Trinity Orthodox Church requests a Special Use Permit for dormitory boarding and monastery use. The property is zoned R-1 (Residential, one dwelling unit per acre) and is located at 207 East Cordova Road. (William Lamboy, Case Manager) Case #2012-71. School for Advanced Research Special Use Permit. JenkinsGavin Design and Development, agents for School for Advanced Research, request a Special Use Permit to aI/ow a museum use at 660 Garcia Street. The property is zoned R-2 (Residential, two dwelling units per acre) and R-3 (Residential, three dwelling units per acre). (William Lamboy, Case Manager) H. BUSINESS FROM THE FLOOR I. -

00 TZ Konstantin Nulte:Layout 1.Qxd

Tibor Živković DE CONVERSIONE CROATORUM ET SERBORUM A Lost Source INSTITUTE OF HISTORY Monographs Volume 62 TIBOR ŽIVKOVIĆ DE CONVERSIONE CROATORUM ET SERBORUM A Lost Source Editor-in-chief Srđan Rudić, Ph.D. Director of the Institute of History Belgrade 2012 Consulting editors: Academician Jovanka Kalić Prof. Dr. Vlada Stanković This book has been published with the financial support of THE MINISTRY OF EDUCATION AND SCIENCE OF THE REPUBLIC OF SERBIA (project No III47025) CONTENTS PREFACE 9 ABBREVIATIONS 13 INTRODUCTORY NOTE The Workshop of Constantine Porphyrogenitus 19 THE STORY OF THE CROATS 43 THE STORY OF DALMATIA 91 THE STORY OF THE SERBS 149 THE DISPLACED SECTIONS OF CONSTANTINE’S PRIMARY SOURCE ON THE CROATS AND THE SERBS 181 CONCLUSIONS 197 SOURCES 225 REFERENCES 229 INDEXES 241 Nec plus ultra To the memories of the finest gentleman Božidar Ferjančić (1929 – 1998) PREFACE This book is the result of 20 years of research on the so-called Slavic chapters of Constantine Pophyrogenitus’ De administrando imperio, the last stage of which took place in Athens 2009/2010, where I was completing my postdoctoral research on the supposed main source Constantine Porhyrogenitus had used for the earliest history of the Croats and the Serbs. The research took place at the Centre for Byzantine Research in Athens (IVE) with the financial support of the Ministry of Science and Technology of Serbian Government and the Serbian Orthodox Metropoly of Montenegro. The first preliminary results on the supposed, now lost source of Constantine Porphyrogenitus, were published in an article in Byzantina Symmeikta (2010) and the results I presented at that time allowed me to try to make a more profound analysis of that source and eventually to reveal the most significant number of its fragments preserved in the Croat and Serb chapters of De administrando imperio – its original purpose – as well as the possible background of its composition. -

SCX-920-System-Controller.Pdf

Infinity SCX 920 System Controller The Infinity SCX 920 is a stand-alone, programmable, microprocessor-based system controller that F E A T U R E S is used for Direct Digital Control of chillers, cooling towers, boilers, air handling units, perimeter • Stand-alone DDC for System radiation, lighting, etc. The Infinet’s true peer-to-peer communication protocol provides the Infinity Reliability SCX 920 with the ability to instantly communicate with Infinity network controllers such as the CX • Peer-to-Peer Communications 9200, as well as the entire network of Andover Infinity controllers. Up to 254 SCX 920s can be Provide Transparent Data networked with the Infinity CX family of controllers. Transfer • Plain English® Language The SCX 920 comes standard with a metal cover plate suitable for panel mounting (shown). Simplifies Programming An optional enclosure is available for wall mounting. • Universal Inputs and Outputs for Flexible Control Configurations COMMUNICATIONS Communication to the Infinity SCX 920 is handled via the Infinet bus, a twisted pair, half duplex RS-485 interface. • Expandable I/O Meets Additional Communication is accomplished with a token passing protocol which provides full transparent data transfer between all Point Count Needs Infinity controllers on the network. • Detachable Input/Output INPUTS Connectors for Easy Installation The Infinity SCX 920 is capable of sensing sixteen inputs. Each input can accept a digital (on/off), counter (up to 4 Hz), voltage (0-10 VDC), or temperature signal. • Full Function Manual Overrides Provide Status Feedback OUTPUTS • Optional Display/Keypad for Local The Infinity SCX 920 has eight Universal outputs providing pulse, variable voltage (0 - 20 VDC), variable current, (0 - 20mA) Information Control or on/off control of motors and lighting with Form C relays. -

The Rise of Bulgarian Nationalism and Russia's Influence Upon It

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it. Lin Wenshuang University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wenshuang, Lin, "The rise of Bulgarian nationalism and Russia's influence upon it." (2014). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1548. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1548 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2014 Copyright © 2014 by Lin Wenshuang All Rights Reserved THE RISE OF BULGARIAN NATIONALISM AND RUSSIA‘S INFLUENCE UPON IT by Lin Wenshuang B. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 1997 M. A., Beijing Foreign Studies University, China, 2002 A Dissertation Approved on April 1, 2014 By the following Dissertation Committee __________________________________ Prof. -

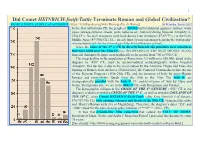

Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: G

1 Did Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle Terminate Roman and Global Civilization? [ROME’S POPULATION CATASTROPHE: https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demografia_di_Roma] G. Heinsohn, January 2021 In the first millennium CE, the people of ROME built residential quarters, latrines, water pipes, sewage systems, streets, ports, bakeries etc., but only during Imperial Antiquity (1- 230s CE). No such structures were built during Late Antiquity (4th-6th/7th c.) or the Early Middle Ages (8th-930s CE). [See already https://q-mag.org/gunnar-heinsohn-the-stratigraphy- of-rome-benchmark-for-the-chronology-of-the-first-millennium-ce.html] Since the ruins of the 3rd c. CE lie directly beneath the primitive new structures that were built after the 930s CE (i.e., BEGINNING OF THE HIGH MIDDLE AGES), Imperial Antiquity belongs stratigraphically to the period from 700 to 930s CE. The steep decline in the population of Rome from 1.5 million to 650,000, dated in the diagram to "450" CE, must be accommodated archaeologically within Imperial Antiquity. This decline is due to the crisis caused by the Antonine Plague and Fires, the burning of Rome's State Archives (Tabularium), the Comet of Commodus before the rise of the Severan Emperors (190s-230s CE), and the invasion of Italy by proto-Hunnic Iazyges and proto-Gothic Quadi from the 160s to the 190s. The 160s ff. are stratigraphically parallel with the 450s ff. CE and its invasion of Italy by Huns and Goths. Stratigraphically, we are in the 860s ff. CE, with Hungarians and Vikings. The demographic collapse in the CRISIS OF THE 6th CENTURY (“553” CE in the diagram) is identical with the CRISIS OF THE 3rd C., as well as with the COLLAPSE OF THE 10th C., when Comet HEINRICH-Swift-Tuttle (after King Heinrich I of Saxony; 876/919-936 CE) with ensuing volcanos and floods of the 930s CE ) damaged the globe and Henry’s Roman style city of Magdeburg). -

1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by St Andrews Research Repository 1 Making a Difference in Tenth-Century Politics: King Athelstan’s Sisters and Frankish Queenship Simon MacLean (University of St Andrews) ‘The holy laws of kinship have purposed to take root among monarchs for this reason: that their tranquil spirit may bring the peace which peoples long for.’ Thus in the year 507 wrote Theoderic, king of the Ostrogoths, to Clovis, king of the Franks.1 His appeal to the ideals of peace between kin was designed to avert hostilities between the Franks and the Visigoths, and drew meaning from the web of marital ties which bound together the royal dynasties of the early-sixth-century west. Theoderic himself sat at the centre of this web: he was married to Clovis’s sister, and his daughter was married to Alaric, king of the Visigoths.2 The present article is concerned with a much later period of European history, but the Ostrogothic ruler’s words nevertheless serve to introduce us to one of its central themes, namely the significance of marital alliances between dynasties. Unfortunately the tenth-century west, our present concern, had no Cassiodorus (the recorder of the king’s letter) to methodically enlighten the intricacies of its politics, but Theoderic’s sentiments were doubtless not unlike those that crossed the minds of the Anglo-Saxon and Frankish elite families who engineered an equally striking series of marital relationships among themselves just over 400 years later. In the early years of the tenth century several Anglo-Saxon royal women, all daughters of King Edward the Elder of Wessex (899-924) and sisters (or half-sisters) of his son King Athelstan (924-39), were despatched across the Channel as brides for Frankish and Saxon rulers and aristocrats. -

The Macedonian Question: a Historical Overview

Ivanka Vasilevska THE MACEDONIAN QUESTION: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW There it is that simple land of seizures and expectations / That taught the stars to whisper in Macedonian / But nobody knows it! Ante Popovski Abstract In the second half of the XIX century on the Balkan political stage the Macedonian question was separated as a special phase from the great Eastern question. Without the serious support by the Western powers and without Macedonian millet in the borders of the Empire, this question became a real Gordian knot in which, until the present times, will entangle and leave their impact the irredentist aspirations for domination over Macedonia and its population by the Balkan countries – Greece, Bulgaria and Serbia. The consequence of the Balkan wars and the World War I was the territorial dividing of ethnic Macedonia. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the territory of Macedonia was divided among Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, an act of the Balkan countries which, instead of being sanctioned has received an approval, with the confirmation of their legitimacy made with the treaties introduced by the Versailles world order. Divided with the state borders, after 1919 the Macedonian nation was submitted to a severe economic exploitation, political deprivation, national non-recognition and oppression, with a final goal - to be ethnically liquidated. In essence, the Macedonian question was not recognized as an ethnic problem because the conditions from the past and the powerful propaganda machines of the three neighboring countries - Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria, made the efforts to make the impression before the world public that the Macedonian ethnicity did not exist, while Macedonia was mainly treated as a geographical term, and the ethnic origin of the population on the Macedonian territory was considered exclusively as a “lost herd”, i.e. -

The Byzantino-Latin Principality of Adrianople and the Challenge of Feudalism (1204/6–Ca

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Ghent University Academic Bibliography The Byzantino-Latin Principality of Adrianople and the Challenge of Feudalism (1204/6–ca. 1227/28) Empire, Venice, and Local Autonomy Filip Van Tricht n the aftermath of the conquest of Constantinople in designated or recognized by Venice as ruler of the city I1204 during the Fourth Crusade, one of many new of Adrianople, the author convincingly argues that political entities that took shape was a relatively short- the principality was no independent state, but a feu- lived principality centered on the city of Adrianople in dal principality within the framework of the (Latin) Thrace. Until recently not much attention had been Empire of Constantinople, a conclusion that for non- devoted to its history or position within the Byzantine Greek authors such as Jean Longnon had been rather space in the first decades of the thirteenth century.1 A self-evident.3 few years ago, however, Benjamin Hendrickx wrote an Along the way Hendrickx also makes some state- article with as starting point the observation that most ments that in my opinion raise new questions and war- Greek scholars until then had always maintained that rant further investigation. First, the author considers the principality in question was an independent state the mentioned Pactum to be an illustration of “Venice’s in the sense of a so-called Territorialstaat or toparchia independent policy in Romania” vis-à-vis the Latin as defined by Jürgen Hoffman.2 Through a renewed emperors.4 I will argue however that there are good rea- analysis of the so-called Pactum Adrianopolitanum sons to challenge this proposition. -

Nominalia of the Bulgarian Rulers an Essay by Ilia Curto Pelle

Nominalia of the Bulgarian rulers An essay by Ilia Curto Pelle Bulgaria is a country with a rich history, spanning over a millennium and a half. However, most Bulgarians are unaware of their origins. To be honest, the quantity of information involved can be overwhelming, but once someone becomes invested in it, he or she can witness a tale of the rise and fall, steppe khans and Christian emperors, saints and murderers of the three Bulgarian Empires. As delving deep in the history of Bulgaria would take volumes upon volumes of work, in this essay I have tried simply to create a list of all Bulgarian rulers we know about by using different sources. So, let’s get to it. Despite there being many theories for the origin of the Bulgars, the only one that can show a historical document supporting it is the Hunnic one. This document is the Nominalia of the Bulgarian khans, dating back to the 8th or 9th century, which mentions Avitohol/Attila the Hun as the first Bulgarian khan. However, it is not clear when the Bulgars first joined the Hunnic Empire. It is for this reason that all the Hunnic rulers we know about will also be included in this list as khans of the Bulgars. The rulers of the Bulgars and Bulgaria carry the titles of khan, knyaz, emir, elteber, president, and tsar. This list recognizes as rulers those people, who were either crowned as any of the above, were declared as such by the people, despite not having an official coronation, or had any possession of historical Bulgarian lands (in modern day Bulgaria, southern Romania, Serbia, Albania, Macedonia, and northern Greece), while being of royal descent or a part of the royal family.