Amaditohero 10 X 8.5 TXT.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry

William & Mary Law Review Volume 38 (1996-1997) Issue 2 Article 5 January 1997 "Of Deaths Put on by Cunning and Forced Cause": Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry Paul A. LeBel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Substance Abuse and Addiction Commons Repository Citation Paul A. LeBel, "Of Deaths Put on by Cunning and Forced Cause": Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry, 38 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 605 (1997), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol38/iss2/5 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr BOOK REVIEW ESSAY "OF DEATHS PUT ON BY CUNNING AND FORCED CAUSE": REALITY BITES THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY THE CIGARETTE PAPERS, by Stanton A. Glantz, John Slade, Lisa A. Bero, Peter Hanauer, and Deborah E. Barnes. University of California Press, Berkeley, Cal., 1996. Pp. 539. $29.95. SMOKESCREEN: THE TRUTH BEHIND THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY COVER-UP, by Philip J. Hilts. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Reading, Mass., 1996. Pp. 253. $22.00. ASHES TO ASHES: AMERICA'S HUNDRED-YEAR CIGARETTE WAR, THE PUBLIC HEALTH, AND THE UNABASHED TRIUMPH OF PHILIP MORRIS, by Richard Kluger. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, N.Y., 1996. Pp. 807. $35.00. PAUL A. LEBEL" Immediately after the death of Hamlet, confronted by de- mands from Fortinbras and the English ambassadors for an ex- planation of what has occurred, Horatio responds: And let me speak to the yet unknowing world How these things came about: so shall you hear Of carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts, Of accidental judgements, casual slaughters, Of deaths put on by cunning and forced cause, And, in this upshot, purposes mistook Fall'n on the inventors' heads: all this can I Truly deliver.1 * James Gould Cutler Professor of Law, College of William & Mary School of Law. -

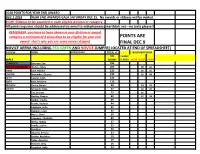

Points Are Final Dec 9

2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 NOVICE ARENA INCLUDING PEA GREEN AND NOVICE JUMPER( LOCATED AT END OF SPREADSHEET) DIVISION RIDER HORSE/PONY TOTAL of NOVEMBER SHOW ALL CHAMP WALK SHOWS CLASSES 11/16 11/17 11/18 CHAMPION Kennedy, Zoe 283 RESERVE CHAMPION Walker, Olivia 265 28 34 THIRD June, Ryland 219 28 34 FOURTH November, Eleanor 193 16 28 FIFTH Connor, Faith 127 SIXTH Britz, Marlene 113 SEVENTH Varley, Harper 90 24 32 EIGHTH Schwartz, Sofie 77 16 20 Fay, Brianna 75 26 Hartley, Reagan 60 32 28 Barber, Crosby 46 Franks, Rachael 44 Lababera, Sofia 32 Zipperer, Layla 32 Hayes, Elana 30 Connover, Charlotte 29 White, Hadley 27 Franks, Sophie 25 Brooklyn 23 Musella, Elenora 23 Dooley, Madeline 19 Dulay, Angelina 17 Bennett, Alley 16 Crawford, Bella 14 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 Crisante, Shannon 14 Lasslet, Penelope 14 Lee, Hadley 13 Yount, Lindsay 13 Palacros, Mia 12 Glazeski, Makayla 10 Hunt, Laura Claire 7 Lane, Ava 6 6 Raveling, Layla 4 Dunham, Caitlyn 3 Glazeski, Emma 3 Schunk, Julie 2 Sean ----last name not completed/legible on entry 1 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. -

Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes*

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS Harold Pinter’s Ashes to Ashes* Marta Ramos Oliveira Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Dr. Ubiratan Paiva de Oliveira Porto Alegre 1999 * Trabalho parcialmente financiado pelo Conselho Nacional do Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). To my mother and those who came before and those who are still to come Because you don’t know where [the pen] had been. You don’t know how many other hands have held it, how many other hands have written with it, what other people have been doing with it. You know nothing of its history. You know nothing of its parents’ history. - DEVLIN TODESFUGE Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken sie abends Wir trinken sie mittags und morgens wir trinken sie nachts Wir trinken und trinken Wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Er schreibt es und tritt vor das Haus und es blitzen die Sterne er pfeift seine Rüden herbei Er pfeift seine Juden hervor läßt schaufeln ein Grab in der Erde Er befiehlt uns spielt auf nun zum Tanz Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken dich nachts Wir trinken sie morgens und mittags und wir trinken dich abends Wir trinken und trinken Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith wir schaufeln ein Grab in -

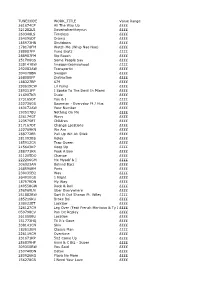

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261674CP All the Way up Гггг 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun Гггг 269348LS Timeless Гггг

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261674CP All The Way Up ££££ 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun ££££ 269348LS Timeless ££££ 254095DT Drama ££££ 185973HN Shutdown ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 288987FP Yung Bratz ££££ 288987FM Rip Roach ££££ 251706GS Some People Say ££££ 338141BW Imsippinteainyohood ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 394078BN Swagon ££££ 268080FP Distraction ££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 273165DT You & I ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 143172AW Your Number ££££ 190517BU Nothing On Me ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 217167DT Change Locations ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 288772ER Pull Up Wit Ah Stick ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 306923AN Behind Barz ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 239035EQ Way ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 187979DN My Way ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 256969LN Uber Everywhere ££££ 251882BW Sort It Out Sharon Ft. Wiley ££££ 285216KU Broke Boi ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 326127CM Leg Over (Feat French Montana & Ty Dolla)££££ (Remix) 059798CV Pon De Replay ££££ 261050BU Location ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 338141CN Skin ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 226119CM Overtime ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 280926KQ Playa No More ££££ 156278GR I Need Your Love ££££ 289817KU Slipknot ££££ 318501EW Ski Mask ££££ 156551CN Alright -

Proceedings of the Art of Death and Dying Symposium

PROCEEDINGS OF THE ART OF DEATH AND DYING SYMPOSIUM OCTOBER 24-27, 2013, UNIVERSITY OF HOUSTON LIBRARIES HOUSTON, TX EDITED BY KATIE BUEHNER, KERRY CREELMAN, CATHERINE ESSINGER, AND ANDREA MALONE PAMELA ALLARA ♦ DIANE VICTOR: ASHES TO ASHES Although “ashes to ashes” is a familiar phrase, its source in the Anglican Church burial service, as codi- fied in the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, is culturally remote today: Forasmuch as it hath pleased Almighty God in his great mercy to take unto himself the soul of our dear brother here departed, we therefore commit his body to the ground; earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust; in sure and certain hope of the Resurrection to eternal life, through our Lord Jesus Christ…1 1 Art of Death & Dying Symposium Proceedings In her Transcend (2010) and Lost Words (2011) FIGURE 1.1 Diane Victor, Transcend (Liz) portraits of old age pensioners, Diane Victor was concerned with “the loss of accumulated informa- tion, wisdom and narrative that occurs when some- one dies,”2 (and the Book of Common Prayer might be considered one such example). She there- fore made the quite radical decision to create the images from the ashes of books that had been im- portant to them. Rather than offering the ‘certain hope of…eternal life,’ the portraits ask us to reflect on the “ephemeral and transient aspects of human mortality”—and South African cultural history in general. Most of the ‘sitters’ are white males, whose status in a democratic South Africa of black majority-rule has become increasingly unstable since 1994. -

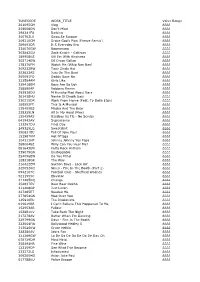

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261095CM

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261095CM Vlog ££££ 259008DN Don't Mind ££££ 298241FU Barking ££££ 300703LV Swag Se Swagat ££££ 309210CM Drake God's Plan (Freeze Remix) ££££ 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 234070GW Boomerang ££££ 302842GU Zack Knight - Galtiyan ££££ 189958KS Kill Em With Kindness ££££ 302714EW Dil Diyan Gallan ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 309232BW Tiger Zinda Hai ££££ 253823AS Juju On The Beat ££££ 265091FQ Daddy Says No ££££ 232584AM Girls Like ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 258890AP Robbery Remix ££££ 292938DU M Huncho Mad About Bars ££££ 261438HU Nashe Si Chadh Gayi ££££ 230215DR Work From Home (Feat. Ty Dolla $Ign) ££££ 188552FT This Is A Musical ££££ 135455BS Masha And The Bear ££££ 238329LN All In My Head (Flex) ££££ 155459AS Bassboy Vs Tlc - No Scrubs ££££ 041942AV Supernanny ££££ 133267DU Final Day ££££ 249325LQ Sweatshirt ££££ 290631EU Fall Of Jake Paul ££££ 153987KM Hot N*Gga ££££ 304111HP Johnny Johnny Yes Papa ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 081643EN Party Rock Anthem ££££ 239079GN Unstoppable ££££ 254096EW Do You Mind ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 216422EM Section Boyz - Lock Arf ££££ 325052KQ Nines - Fire In The Booth (Part 2) ££££ 0942107C Football Club - Sheffield Wednes ££££ 5211555C Elevator ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 254637EV Baar Baar Dekho ££££ 311408GP Just Listen ££££ 227485ET Needed Me ££££ 277854GN Mad Over You ££££ 125910EU The Illusionists ££££ 019619BR I Can't Believe This Happened To Me ££££ 152953AR Fallout ££££ 153881KV Take Back The Night ££££ 217278AV Better When -

Ashes to Ashes - Episode 1 - Shooting Script: PEACH - 31/08/07 1

Ashes to Ashes - Episode 1 - Shooting Script: PEACH - 31/08/07 1. 1 EXT. MODERN LONDON - LONDON CITY LANDSCAPE - DAY 1. 0835 1 The city. Glass spires. Chrome. Winking lights. Incessant noise. 2008 glory. We SMASH CUT from location to gleaming location. MOLLY (V.O.) (12 yrs old) “My name is Sam Tyler. I had an accident and I woke up in 1973. Was I mad? In a coma? Back in time? Whatever had happened, it was like I’d landed on a different planet. If I could figure out why I was here then maybe I could get home ...” Yeah, whatever. That is so lame. CUT TO: 2 I/E. ALEX’S CAR - STREETS - DAY 1. 0836 2 MOLLY DRAKE, bright, confident Catholic schoolgirl, rifles through her mother’s case files. DI ALEX DRAKE at the wheel, struggling to programme her sat-nav. ALEX (only half-serious) Return the classified document, thank you ... What did Evan get you? Molly ...? MOLLY A Blackberry. ALEX I’ll get you some more while you’re at school and you can make a birthday crumble. MOLLY Mum .... what we were talking about, I will look after it and ... ALEX And feed it crackers every day? That’s what parrots eat love, “Polly want a cracker?” MOLLY giggles - gives her mum’s seat a teasing punch. ALEX (CONT'D) Did your dad ...? MOLLY No. He’s in Canada with Judy. (changing the subject) So this guy, Taylor ... (CONTINUED) Ashes to Ashes - Episode 1 - Shooting Script: PEACH - 31/08/07 2. 2 CONTINUED: 2 ALEX Tyler. -

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P. E. 5772 - 15 Caught Up In You .38 Special 5816 - 08 Hold On Loosely .38 Special 5772 - 08 If I'd Been The One .38 Special 5950 - 06 Second Chance .38 Special 4998 - 05 Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation 4998 - 06 While We're Young 1 Girl Nation 5915 - 18 Beautiful 10 Years 5881 - 11 Through The Iris 10 Years 6085 - 15 Wasteland 10 Years 5459 - 07 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 5218 - 08 Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs 1046A -08 These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs 5246 - 14 I'm Not In Love 10cc 6274 - 20 Things We Do For Love, The 10cc 5541 - 04 Cupid 112 5449 - 10 Dance With Me 112 5865 - 18 Peaches And Cream 112 5883 - 04 Right Here For You 112 6037 - 07 U Already Know 112 5790 - 02 Hot And Wet 112 & Ludacris 5689 - 04 Na Na Na 112 & Super Cat 5431 - 05 We Are One 12 Stones 5210 - 20 Chocolate 1975, The 6386 - 01 If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 1975, The 5771 - 18 Love Me 1975, The 6371 - 08 Me And You Together Song (Clean) 1975, The 6070 - 19 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 1975, The 5678 - 02 I'm Different (Clean) 2 Chainz 5673 - 05 No Lie (Clean) 2 Chainz & Drake 5663 - 12 Birthday Song (Clean) 2 Chainz & Kanye West 5064 - 20 Feds Watching (Clean) 2 Chainz & Pharrell 5450 - 20 We Own It 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa 5293 - 09 I Do It (Clean) 2 Chainz Feat. -

55954 Songs, 137.5 Days, 339.51 GB Page 1 of 96 Artist Album

Page 1 of 96 Music 55954 songs, 137.5 days, 339.51 GB Artist Album # Items Total Time A-1 Mash Confusion 18 1:11:30 A-Team Haiku D'Etat - Coup De Theatre 13 55:37 A-Team Haiku D'Etat - Haiku D'Etat 13 1:12:37 A-Team Who Reframed The A-Team? 15 1:07:35 A$AP Rocky Goldie 11 37:47 A$AP Rocky Live.Love.A$AP 16 53:49 A$AP Rocky Long.Live.A$AP 16 1:05:02 A.B.N. A.B.N. (Assholes By Nature) 30 1:32:14 A.B.N. It Is What It Is 18 1:12:37 A.D.O.R. Animal 2000 12 34:18 A.D.O.R. Classic Bangers Volume 1 16 59:53 A.D.O.R. The Concrete 17 55:25 A.D.O.R. Shock Frequency 16 44:28 A.D.O.R. Signature of The Ill 12 41:27 AB-Soul Control System 17 1:11:52 AB-Soul Longterm Mentality 13 55:01 Above The Law Black Mafia Life 15 1:11:24 Above The Law Legends 16 1:04:39 Above The Law Livin' Like Hustlers 10 45:59 Above The Law Time Will Reveal 15 1:06:38 Above The Law Uncle Sam's Curse 12 1:00:19 Above The Law Vocally Pimpin 9 38:50 Abstract Rude Code Name Scorpion 13 51:55 Abstract Rude Making More Tracks 15 1:01:28 Abstract Rude Making Tracks 21 1:12:11 Abstract Rude Rejuvenation 14 52:15 Abstract Rude & Tribe Unique P.A.I.N.T. -

UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title "Watching Their Souls Speak": Interpreting the New Music Videos of Childish Gambino, Kendrick Lamar, and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5gw3v7bf Author Lindmark, Sarah Allison Publication Date 2019 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE “Watching Their Souls Speak”: Interpreting the New Music Videos of Childish Gambino, Kendrick Lamar, and Beyoncé Knowles-Carter THESIS submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS in Music by Sarah Allison Lindmark Thesis Committee: Assistant Professor Nicole Grimes, Chair Professor Nicole Mitchell Assistant Professor Stephan Hammel 2019 © 2019 Sarah Allison Lindmark TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ......................................................................................................................... iii ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS ................................................................................................................... iv INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 CHAPTER ONE ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Iconic Memory and Signifyin(g)............................................................................................................