Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

Books Added to Benner Library from Estate of Dr. William Foote

Books added to Benner Library from estate of Dr. William Foote # CALL NUMBER TITLE Scribes and scholars : a guide to the transmission of Greek and Latin literature / by L.D. Reynolds and N.G. 1 001.2 R335s, 1991 Wilson. 2 001.2 Se15e Emerson on the scholar / Merton M. Sealts, Jr. 3 001.3 R921f Future without a past : the humanities in a technological society / John Paul Russo. 4 001.30711 G163a Academic instincts / Marjorie Garber. Book of the book : some works & projections about the book & writing / edited by Jerome Rothenberg and 5 002 B644r Steven Clay. 6 002 OL5s Smithsonian book of books / Michael Olmert. 7 002 T361g Great books and book collectors / Alan G. Thomas. 8 002.075 B29g Gentle madness : bibliophiles, bibliomanes, and the eternal passion for books / Nicholas A. Basbanes. 9 002.09 B29p Patience & fortitude : a roving chronicle of book people, book places, and book culture / Nicholas A. Basbanes. Books of the brave : being an account of books and of men in the Spanish Conquest and settlement of the 10 002.098 L552b sixteenth-century New World / Irving A. Leonard ; with a new introduction by Rolena Adorno. 11 020.973 R824f Foundations of library and information science / Richard E. Rubin. 12 021.009 J631h, 1976 History of libraries in the Western World / by Elmer D. Johnson and Michael H. Harris. 13 025.2832 B175d Double fold : libraries and the assault on paper / Nicholson Baker. London booksellers and American customers : transatlantic literary community and the Charleston Library 14 027.2 R196L Society, 1748-1811 / James Raven. -

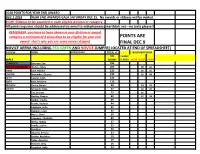

Points Are Final Dec 9

2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 NOVICE ARENA INCLUDING PEA GREEN AND NOVICE JUMPER( LOCATED AT END OF SPREADSHEET) DIVISION RIDER HORSE/PONY TOTAL of NOVEMBER SHOW ALL CHAMP WALK SHOWS CLASSES 11/16 11/17 11/18 CHAMPION Kennedy, Zoe 283 RESERVE CHAMPION Walker, Olivia 265 28 34 THIRD June, Ryland 219 28 34 FOURTH November, Eleanor 193 16 28 FIFTH Connor, Faith 127 SIXTH Britz, Marlene 113 SEVENTH Varley, Harper 90 24 32 EIGHTH Schwartz, Sofie 77 16 20 Fay, Brianna 75 26 Hartley, Reagan 60 32 28 Barber, Crosby 46 Franks, Rachael 44 Lababera, Sofia 32 Zipperer, Layla 32 Hayes, Elana 30 Connover, Charlotte 29 White, Hadley 27 Franks, Sophie 25 Brooklyn 23 Musella, Elenora 23 Dooley, Madeline 19 Dulay, Angelina 17 Bennett, Alley 16 Crawford, Bella 14 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 Crisante, Shannon 14 Lasslet, Penelope 14 Lee, Hadley 13 Yount, Lindsay 13 Palacros, Mia 12 Glazeski, Makayla 10 Hunt, Laura Claire 7 Lane, Ava 6 6 Raveling, Layla 4 Dunham, Caitlyn 3 Glazeski, Emma 3 Schunk, Julie 2 Sean ----last name not completed/legible on entry 1 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. -

International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Vol

Literary Journalism Studies e Journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2017 Information for Contributors 4 Note from the Editor 5 Ted Conover and the Origins of “Immersion” in Literary Journalism by Patrick Walters 8 Pioneering Style: How the Washington Post Adopted Literary Journalism by omas R. Schmidt 34 Literary Journalism and Empire: George Warrington Steevens in Africa, 1898–1900 by Andrew Griths 60 T LJ e Ammo for the Canon: What Literary Journalism Educators Teach by Brian Gabrial and Elyse Amend 82 D LJ Toward a New Aesthetic of Digital Literary Journalism: Charting the Fierce Evolution of the “Supreme Nonction” by David O. Dowling 100 R R Recent Trends and Topics in Literary Journalism Scholarship by Roberta Maguire and Miles Maguire 118 S-P Q+A Kate McQueen Interviews Leon Dash 130 B R Martha Nandorfy on Behind the Text, Doug Cumming on e Redemption of Narrative, Rosemary Armao on e Media and the Massacre, Nancy L. Roberts on Newswomen, Brian Gabrial on Literary Journalism and World War I, and Patrick Walters on Immersion 141 Mission Statement 162 International Association for Literary Journalism Studies 163 2 Literary Journalism Studies, Vol. 9, No. 1, Spring 2017 Copyright © 2017 International Association for Literary Journalism Studies All rights reserved Website: www.literaryjournalismstudies.org Literary Journalism Studies is the journal of the International Association for Literary Journalism Studies and is published twice yearly. For information on subscribing or membership, go to www.ialjs.org. M Council of Editors of Learned Journals Published twice a year, Spring and Fall issues. -

Select List of New Material -- Added in February 2013 Call Number Title Publisher Date

Select List of New Material -- added in February 2013 Call number Title Publisher Date Child psychology : development in a changing society / Robin BF721 .V345 2008 John Wiley & Sons, c2008. Harwood, Scott A. Miller, Ross Vasta. Indiana University BX1378 .P49 2000 Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930-1965 / Michael Phayer. c2000. Press, D25.5 .K27 1995 On the origins of war and the preservation of peace / Donald Kagan. Doubleday, 1995. Dynamics of global dominance : European overseas empires, 1415- D210 .A19 2000 Yale University Press, c2000. 1980 / David B. Abernethy. Knopf : Distributed by D210 .T89 1984 March of folly : from Troy to Vietnam / Barbara W. Tuchman. 1984. Random House, Birth of the modern world, 1780-1914 : global connections and D295 .B28 2004 Blackwell Pub., 2004. comparisons / C.A. Bayly. Belknap Press of D359.7 .W67 2012 World connecting, 1870-1945 / edited by Emily S. Rosenberg. Harvard University 2012. Press, Unfinished peace after World War I : America, Britain and the Cambridge University D727 .C58 2008 2008 [2006]. stabilisation of Europe, 1919-1932 / Patrick O. Cohrs. Press, How war came : the immediate origins of the Second World War, 1938- D741 .W36 1989 Pantheon Books, 1989. 1939 / Donald Cameron Watt. D756.5.N6 H35 1984 Overlord : D-Day and the battle for Normandy / Max Hastings. Simon and Schuster, c1984. D764 .W48 2000 Russia at war, 1941-1945 / Alexander Werth. Carroll & Graf, 2000. Forgotten Holocaust : the Poles under German occupation, 1939-1944 D802.P6 L85 1997 Hippocrene, 1997. / Richard C. Lukas. Blue and the yellow stars of David : the Zionist leadership in Palestine Harvard University D804.3 .P6713 1990 1990. -

Harold Pinter's Ashes to Ashes*

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS Harold Pinter’s Ashes to Ashes* Marta Ramos Oliveira Dissertação realizada sob a orientação do Dr. Ubiratan Paiva de Oliveira Porto Alegre 1999 * Trabalho parcialmente financiado pelo Conselho Nacional do Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq). To my mother and those who came before and those who are still to come Because you don’t know where [the pen] had been. You don’t know how many other hands have held it, how many other hands have written with it, what other people have been doing with it. You know nothing of its history. You know nothing of its parents’ history. - DEVLIN TODESFUGE Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken sie abends Wir trinken sie mittags und morgens wir trinken sie nachts Wir trinken und trinken Wir schaufeln ein Grab in den Lüften da liegt man nicht eng Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Er schreibt es und tritt vor das Haus und es blitzen die Sterne er pfeift seine Rüden herbei Er pfeift seine Juden hervor läßt schaufeln ein Grab in der Erde Er befiehlt uns spielt auf nun zum Tanz Schwarze Milch der Frühe wir trinken dich nachts Wir trinken sie morgens und mittags und wir trinken dich abends Wir trinken und trinken Ein Mann wohnt im Haus der spielt mit den Schlangen der schreibt Der schreibt wenn es dunkelt nach Deutschland dein goldenes Haar Margarete Dein aschenes Haar Sulamith wir schaufeln ein Grab in -

American Studies Department, School of Arts and Sciences; and Planning and Public Policy Program, Bloustein School of Planning A

American Studies Department, School of Arts and Sciences; and Planning and Public Policy Program, Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, both Rutgers University American Land, 01:050:444:01 and 10:762:444, Spring 2012, 3 credits Monday, 12:35-3:35, Ruth Adams Building, Room 018, Douglass Campus Taught by Frank Popper, Civic Square Building, Room 356, College Avenue Campus, 848-732- 2790, [email protected], [email protected] Office hours: Thursday afternoon, before or after class, or by appointment Readings: Joan Didion, “Where I Was From” (2003, ISBN 0-679-75286-2), Jarid Manos, “Ghetto Plainsman” (second edition, 2009, ISBN 13: 978-0-9668413-4-3), and Ted Steinberg, “Down to Earth: Nature’s Role in American History” (second edition, 2009, ISBN 13: 978-0-19- 533182-0). All are in paperback at the Rutgers/Barnes & Noble Bookstore. There may be other, shorter readings as needed. The goal of the course is to provide an advanced-undergraduate understanding of the diverse connections between America’s national development and land environment. Taking an ecological approach, the course examines how the United States originated, then expanded to cover a continental land mass, and in what ways the expansion changed the nation. It explores how, why and with what results major parts of the U.S. economy—for instance, farming, industry, energy, services and government—have grown or in some cases shrunk. It examines how and with what consequences the U.S. has incorporated different ethnic and racial groups. It looks at how, why and with what results it has conducted its foreign policy and globalized. -

The Ridgefield Encyclopedia ===

=== THE RIDGEFIELD ENCYCLOPEDIA === A compendium of nearly 4,500 people, places and things relating to Ridgefield, Connecticut. by Jack Sanders [Note: Abbreviations and sources are explained at the end of the document. This work is being constantly expanded and revised; this version was updated on 4-27-2021.] A A&P: The Great Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company opened a small grocery store at 378 Main Street in 1948 (long after liquor store — q.v.); moved to 378 Main Street in the Bissell Building in the early 1940s. It became a supermarket at 46 Danbury Road in 1962 (now Walgreens site); closed November 1981. [JFS] [DD100] A&P Liquor Store: Opened at ONS133½ Main Street Sept. 12, 1935; [P9/12/1935] later was located at ONS86 Main Street. [1940 telephone directory] Aaron’s Court: A short, dead-end road serving 9 of 10 lots at 45 acre subdivision on the east side of Ridgebury Road by Lewis and Barry Finch, father-son, who had in 1980 proposed a corporate park here; named for Aaron Turner (q.v.), circus owner, who was born nearby. [RN] A Better Chance (ABC) is Ridgefield chapter of a national organization that sponsors talented, motivated children from inner-cities to attend RHS; students live at 32 Fairview Avenue; program began 1987 with six students. A Birdseye View: Column in Ridgefield Press for many years, written by Duncan Smith (q.v.) Abbe family: Lived on West Lane and West Mountain, 1935-36: James E. Abbe, noted photographer of celebrities, his wife, Polly Shorrock Abbe, and their three children Patience, Richard and John; the children became national celebrities when their 1936 book, Around the World in Eleven Years. -

Review: Michael Meltsner, the Making of a Civil Rights Lawyer

REVIEW: MICHAEL MELTSNER, THE MAKING OF A CIVIL RIGHTS LAWYER James R. Ralph, Jr.* In the middle of The Making of a Civil Rights Lawyer, Michael Meltsner recalls the first time he met William Kunstler. It was in late 1961, shortly after Meltsner had joined the NAACP Legal and Education Defense Fund (LDF). Kunstler had not yet, Meltsner remembers, “been overtaken by fame.”1 A meeting on representing civil rights workers was about to begin when a call came in about arrests in Poplarville, Mississippi, a hard- nosed Delta town where only two years earlier a black man had been lynched for allegedly raping a white woman. Kunstler immediately demanded action. “We have to get there now,” he boomed. “This is Poplarville. I mean Poplarville!”2 Kunstler was already showing the impulsive traits that would make him one of the most well-known civil rights lawyers in the country. “Unfortunately,” Meltsner adds, “as time went by, he developed a habit of crisscrossing the South and filing a wild array of cases—an itinerant, a sort of legal Johnny Appleseed—that other lawyers would have to take over after he moved on.”3 Meltsner does not say whether he actually had to pick up after Kunstler, but he certainly fits the description of those who did—hard working, committed, and unlikely to be featured in newspapers or on television. As a result, Meltsner has not figured prominently in the leading histories of civil rights litigation in the 1960s, but that does not mean that his new book is a secondary account by a minor player.4 He offers an insider’s view of the work of LDF (arguably the most important public interest legal organization in the country’s history); a far-ranging yet clear- headed meditation on law, social change, and the struggle for racial equality; and candid commentary on the virtues of being a public interest lawyer by a veteran practitioner. -

Planned Instruction

DELAWARE VALLEY SCHOOL DISTRICT PLANNED INSTRUCTION A PLANNED COURSE FOR: Advanced Placement (AP) English Language and Composition Grade Level: 11/12 Date of Board Approval: ______2018_______________ 1 DELAWARE VALLEY SCHOOL DISTRICT Planned Instruction Title of Planned Instruction: Advanced Placement English Language & Composition Subject Area: English Language Arts Grade(s): 11/12 General Course Description: The AP English Language and Composition course aligns to an introductory college-level rhetoric and writing curriculum, which requires students to develop evidence-based analytic and argumentative essays that proceed through several stages or drafts. Students evaluate, synthesize, and cite research to support their arguments. Throughout the course, students develop a personal style by making appropriate grammatical choices. Additionally, students read and analyze the rhetorical elements and their effects in non-fiction texts, including graphic images as forms of text, from many disciplines and historical periods. Reading: According to the College Board, reading in this course builds on the reading done in previous English courses. Students are required to read deliberately and thoroughly, taking time to understand a work’s complexity, to absorb its richness of meaning, and to analyze how that meaning is embodied in literary prose. Writing: Writing is an integral part of the AP English Language and Composition course and of the AP Exam. Writing assignments in the course will address the critical analysis of literary prose and will include expository, analytical, and argumentative essays. The goal of writing assignments is to increase students’ abilities to clearly and cogently explain and analyze what she/he comprehends about literary prose and how she/he interprets them. -

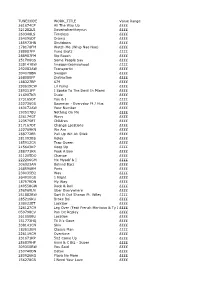

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 261674CP All the Way up Гггг 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun Гггг 269348LS Timeless Гггг

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 261674CP All The Way Up ££££ 321282LS Iloveitwhentheyrun ££££ 269348LS Timeless ££££ 254095DT Drama ££££ 185973HN Shutdown ££££ 178176FM Watch Me (Whip Nae Nae) ££££ 288987FP Yung Bratz ££££ 288987FM Rip Roach ££££ 251706GS Some People Say ££££ 338141BW Imsippinteainyohood ££££ 292083AW Transportin ££££ 394078BN Swagon ££££ 268080FP Distraction ££££ 188327BP 679 ££££ 290619CW Lil Pump ££££ 289311FP I Spoke To The Devil In Miami ££££ 216907KR Dude ££££ 273165DT You & I ££££ 222736GU Baseman - Everyday Ft J Hus ££££ 143172AW Your Number ££££ 190517BU Nothing On Me ££££ 236174GT Wavy ££££ 223575ET Children ££££ 217167DT Change Locations ££££ 222769KN We Are ££££ 288772ER Pull Up Wit Ah Stick ££££ 281093BS Rolex ££££ 185912CR Trap Queen ££££ 215643KP Keep Up ££££ 288771KR Peek A Boo ££££ 311205DQ Change ££££ 222206GM Me Myself & I ££££ 306923AN Behind Barz ££££ 268596EM Paris ££££ 239035EQ Way ££££ 264910GU 1 Night ££££ 187979DN My Way ££££ 249558GW Rock & Roll ££££ 256969LN Uber Everywhere ££££ 251882BW Sort It Out Sharon Ft. Wiley ££££ 285216KU Broke Boi ££££ 238022ET Lockjaw ££££ 326127CM Leg Over (Feat French Montana & Ty Dolla)££££ (Remix) 059798CV Pon De Replay ££££ 261050BU Location ££££ 151773HQ Til It's Gone ££££ 338141CN Skin ££££ 182512EN Classic Man ££££ 226119CM Overtime ££££ 231671KP 502 Come Up ££££ 286839HP 6ixvi & C Biz - Super ££££ 309350BW You Said ££££ 250740DN Detox ££££ 280926KQ Playa No More ££££ 156278GR I Need Your Love ££££ 289817KU Slipknot ££££ 318501EW Ski Mask ££££ 156551CN Alright