Proceedings of the Art of Death and Dying Symposium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

Serbia Belgrade

Issue No. 205 Thursday, April 28 - Thursday, May 12, 2016 ORDER DELIVERY TO Celebrating Author BIRN’s YOUR DOOR +381 11 4030 303 Easter, urges women Kosovo war [email protected] - - - - - - - ISSN 1820-8339 1 Serbian to live more crimes film debuts BELGRADE INSIGHT IS PUBLISHED BY 0 1 style fully in Serbia Page 4 Page 6 Page 10 9 7 7 1 8 2 0 8 3 3 0 0 0 Even when the Democrats longas continue to likely is This also are negotiations Drawn-out Surely the situation is urgent Many of us who have experi We feel in-the-know because bia has shown us that (a.) no single no (a.) that us shown has bia party or coalition will ever gain the governa form to required majority negotiations political (b.) and ment, will never be quickly concluded. achieved their surprising result at last month’s general election, quickly itbecame clear that the re sult was actually more-or-less the result election other every as same in Serbia, i.e. inconclusive. as Serbia’s politicians form new political parties every time disagree with they their current party reg 342 currently are (there leader political parties in Serbia). istered the norm. One Ambassador Belgrade-based recently told me he was also alarmed by the distinct lack of urgency among politicians. Serbian “The country is standstill at and a I don’t understand their logic. If they are so eager to progress towards the EU and en theycome how investors, courage go home at 5pm sharp and don’t work weekends?” overtime. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Exhibition Brochure

SKELETONS OF WAR EXHIBITION CHECKLIST Many of the works in this exhibition were inspired by the horrors experienced by SCIENCE & MEDICINE THE COMING OF DEATH soldiers and civilians in war-torn regions. World War I, among the most devastating conflicts, 1. “The Skeletal System,” from Andrew Combe, M.D., 9. Artist unknown (German), Horsemen of the The Principles of Physiology applied to the Apocalypse, sixteenth century, woodblock, left Europe and its people broken and Preservation of Health, and to the improvement of 3 x 2 ½ in. (7.6 x 6.4 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, changed. Reeling from the horrors Physical and Mental Education (New York: Harper 1983.5.82.c BONES and Brothers, 1836), Dickinson College Archives and they experienced, artists reacted in Special Collections. 10. Circle of Albrecht Dürer, Horsemen of the Representing the Macabre Apocalypse, sixteenth century, woodblock, 3 x 3 in. varying ways. During the decades 2. Abraham Blooteling, View of the Muscles and Tendons (7.6 x 7.6 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, 1983.5.83.d following the war, expressionism of the Forearm of the Left Hand, plate 68 from Govard Bidloo, Anatomi humani corporis centum et 11. Artist unknown, Apocalyptic Vision, sixteenth reached its peak in dark, emotionally- quinque tabulis (Amsterdam: Joannes van Someren, century, woodblock, 2 x 2 3/8 in. March 5–April 18, 2015 1685), engraving and etching, 16 5/8 x 13 in. (47.3 x 33 (5.1 x 6 cm). Gift of Prof. Julius Held, 1983.5.79.a charged artworks, as in the suite of cm). -

Core Like a Rock: Luther’S Theological Center

OCTOBER 2, 2017 CORE LIKE A ROCK: LUTHER’S THEOLOGICAL CENTER Kenneth A. Cherney, Jr., PhD WISCONSIN LUTHERAN SEMINARY CORE LIKE A ROCK: LUTHER’S THEOLOGICAL CENTER You have asked me in this essay to “review the central core of Luther’s confession of divine revelation.” That is interestingly put. Lots of things have cores, and they function in different ways. Apples have cores that you throw away. When I was growing up, Milwaukee had its “inner core,” defined in 1960 by a special mayoral commission as the area between Juneau Avenue on the south, 20th Street on the west, Holton Street on the east, and Keefe Avenue on the north—a blighted part of town, so they said, where people from my tribe didn’t go.1 The earth’s “core” is a glob of molten nickel/iron wrapped around a solid iron ball, and those who claim to know these things say our core generated the heat that caused Florida to break off from Africa and remain stuck on Georgia and Alabama,2 for which many persons are grateful. The “core” of a nuclear reactor is like that; it’s where the fissionable material is found and where the reaction happens that is the whole point. So is the cylinder of “core” muscles around your abdomen, without which you can have biceps the size of Dwayne Johnson’s and when the bad guys show up you’re still basically George McFly, only in a tighter shirt. That is how I understand my assignment. You want to hear about Luther’s spiritual fulcrum, the point around which everything turned. -

Death with a Bonus Pack. New Age Spirituality, Folk Catholicism, and The

Archives de sciences sociales des religions 153 | janvier-mars 2011 Prisons et religions en Europe | Religions amérindiennes et New Age Death with a Bonus Pack New Age Spirituality, Folk Catholicism, and the Cult of Santa Muerte Piotr Grzegorz Michalik Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/assr/22800 DOI: 10.4000/assr.22800 ISSN: 1777-5825 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 31 March 2011 Number of pages: 159-182 ISBN: 978-2-71322301-3 ISSN: 0335-5985 Electronic reference Piotr Grzegorz Michalik, « Death with a Bonus Pack », Archives de sciences sociales des religions [Online], 153 | janvier-mars 2011, Online since 26 May 2011, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/assr/22800 ; DOI : 10.4000/assr.22800 © Archives de sciences sociales des religions Piotr Grzegorz Michalik Death with a Bonus Pack New Age Spirituality, Folk Catholicism, and the Cult of Santa Muerte Introduction A recent visitor to Mexico is very likely to encounter the striking image of Santa Muerte (Saint Death), a symbol of the cult that has risen to prominence across the country. Hooded, scythe-carrying skeleton bares its teeth at street market stalls, on magazine covers and t-shirts. The new informal saint gains popularity not only in Mexico but also in Salvador, Guatemala and the United States. At the turn of the 21st century, the cult of Santa Muerte was associated almost exclusively with the world of crime: drug dealers, kidnappers and prosti- tutes. Responsibility for this distorted image of the cult laid mostly with biased articles in everyday newspapers such as La Crónica and Reforma. -

Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry

William & Mary Law Review Volume 38 (1996-1997) Issue 2 Article 5 January 1997 "Of Deaths Put on by Cunning and Forced Cause": Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry Paul A. LeBel Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Substance Abuse and Addiction Commons Repository Citation Paul A. LeBel, "Of Deaths Put on by Cunning and Forced Cause": Reality Bites the Tobacco Industry, 38 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 605 (1997), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol38/iss2/5 Copyright c 1997 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr BOOK REVIEW ESSAY "OF DEATHS PUT ON BY CUNNING AND FORCED CAUSE": REALITY BITES THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY THE CIGARETTE PAPERS, by Stanton A. Glantz, John Slade, Lisa A. Bero, Peter Hanauer, and Deborah E. Barnes. University of California Press, Berkeley, Cal., 1996. Pp. 539. $29.95. SMOKESCREEN: THE TRUTH BEHIND THE TOBACCO INDUSTRY COVER-UP, by Philip J. Hilts. Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., Reading, Mass., 1996. Pp. 253. $22.00. ASHES TO ASHES: AMERICA'S HUNDRED-YEAR CIGARETTE WAR, THE PUBLIC HEALTH, AND THE UNABASHED TRIUMPH OF PHILIP MORRIS, by Richard Kluger. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, N.Y., 1996. Pp. 807. $35.00. PAUL A. LEBEL" Immediately after the death of Hamlet, confronted by de- mands from Fortinbras and the English ambassadors for an ex- planation of what has occurred, Horatio responds: And let me speak to the yet unknowing world How these things came about: so shall you hear Of carnal, bloody, and unnatural acts, Of accidental judgements, casual slaughters, Of deaths put on by cunning and forced cause, And, in this upshot, purposes mistook Fall'n on the inventors' heads: all this can I Truly deliver.1 * James Gould Cutler Professor of Law, College of William & Mary School of Law. -

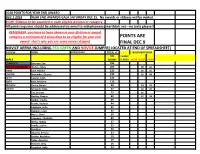

Points Are Final Dec 9

2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 NOVICE ARENA INCLUDING PEA GREEN AND NOVICE JUMPER( LOCATED AT END OF SPREADSHEET) DIVISION RIDER HORSE/PONY TOTAL of NOVEMBER SHOW ALL CHAMP WALK SHOWS CLASSES 11/16 11/17 11/18 CHAMPION Kennedy, Zoe 283 RESERVE CHAMPION Walker, Olivia 265 28 34 THIRD June, Ryland 219 28 34 FOURTH November, Eleanor 193 16 28 FIFTH Connor, Faith 127 SIXTH Britz, Marlene 113 SEVENTH Varley, Harper 90 24 32 EIGHTH Schwartz, Sofie 77 16 20 Fay, Brianna 75 26 Hartley, Reagan 60 32 28 Barber, Crosby 46 Franks, Rachael 44 Lababera, Sofia 32 Zipperer, Layla 32 Hayes, Elana 30 Connover, Charlotte 29 White, Hadley 27 Franks, Sophie 25 Brooklyn 23 Musella, Elenora 23 Dooley, Madeline 19 Dulay, Angelina 17 Bennett, Alley 16 Crawford, Bella 14 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. No awards or ribbons will be mailed. EIGHT Ribbons to be awarded in each eligible division or category. All points inquiries should be addressed via email to [email protected] texts please!! REMEMBER -you have to have shown in your division or award category a minimum of 4 show days to be eligible for year end POINTS ARE award--that's why you see some names skipped FINAL DEC 9 Crisante, Shannon 14 Lasslet, Penelope 14 Lee, Hadley 13 Yount, Lindsay 13 Palacros, Mia 12 Glazeski, Makayla 10 Hunt, Laura Claire 7 Lane, Ava 6 6 Raveling, Layla 4 Dunham, Caitlyn 3 Glazeski, Emma 3 Schunk, Julie 2 Sean ----last name not completed/legible on entry 1 2018 POINTS FOR YEAR END AWARD DEC 1 2018 YEAR END AWARDS GALA SATURDAY DEC 15. -

Yolandi Visser from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Yolandi Visser From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Anri du Toit[4] (born 3 March 1984),[3] better known by her stage name Yolandi Visser (stylized as ¥o-landi Vi$$er), is best Yolandi Visser known as a vocalist in the South African rap-rave group Die Antwoord.[5] Contents 1 Career 1.1 Die Antwoord 1.2 Film 2 Personal life 3 Discography 4 See also 5 References 6 External links Career Yolandi was a part of the music and art groups The Constructus Corporation and MaxNormal.tv.[6] The former was a project that produced a concept album/graphic novel[7] while the latter was a South African 'corporate' hip-hop group in which Yolandi's role was portraying Max Normal's personal assistant. She appeared in several of their music/art videos. Visser at the 2010 Coachella Valley Music and Die Antwoord Arts Festival Background information Die Antwoord is a rap-rave group consisting of Yolandi Visser, Ninja (Watkin Tudor Jones) and DJ Hi-Tek (Justin de Nobrega). [4][8] Birth name Anri du Toit Visser cites Nirvana, PJ Harvey, Nine Inch Nails, Cypress Hill, Eminem, Marilyn Manson and Aphex Twin as musical influences.[3] Also known as Yo-Landi Visser[1] Film Anica The Snuffling[2] Born 3 March 1984 [3] Visser co-starred with Ninja in the 2015 film Chappie, directed by Neill Blomkamp, a fellow South African.[9] Yolandi and Ninja also Port Alfred, Eastern Cape, [10] starred in a short film called Umshini Wam directed by Harmony Korine and released in 2011. South Africa Genres Alternative hip hop, rave, Personal life electronic, zef Occupation(s) Singer Visser was born in Port Alfred, Eastern Cape, South Africa. -

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt's Work Is Highly Recognizable

Gustav Klimt (1862-1918) Gustav Klimt’s work is highly recognizable around the world. He has a reputation as being one of the foremost painters of his time. He is regarded as one the leaders in the Viennese Secessionist movement. During his lifetime and up until the mid-twentieth century, Klimt’s work was not known outside the European art world. Gustav Klimt was born on July 14, 1862 in Baumgarten, near Vienna. He was the second child of seven born to a Bohemian engraver of gold and silver. His father’s profession must have rubbed off on his children. Klimt’s brother Georg became a goldsmith, his brother Ernst joined Gustav as a painter. At the age of 14, Klimt went to the School of Arts and Crafts at the Royal and Imperial Austrian Museum for Art and Industry in Vienna along with his brother. Klimt’s training was in applied art techniques like fresco painting, mosaics and the history of art and design. He did not have any formal painting training. Klimt, his brother Ernst and friend Franz Matsch earned a living creating architectural decorations on commission. They worked on villas and theaters and made money on the side by painting portraits. Klimt’s major break came when the trio helped their teacher paint murals in Kunsthistorische Museum in Vienna. His work helped him begin gain the job of painting interior murals and ceilings in large public buildings on the Ringstraße, including a successful series of "Allegories and Emblems". His work on murals in the Burgtheater in Vienna earned him in 1888 a Golden order of Merit by Franz Josef I of Austria and he became an honorary member of the University of Munich and the University of Vienna. -

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1Wayfrank Ayegirl

Report Artist Release Tracktitle Streaming 2017 1wayfrank Ayegirl - Single Ayegirl Streaming 2017 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Best of 2 Brothers On the 4th Floor Dreams (Radio Version) Streaming 2017 2 Chainz TrapAvelli Tre El Chapo Jr Streaming 2017 2 Unlimited Get Ready for This - Single Get Ready for This (Yar Rap Edit) Streaming 2017 3LAU Fire (Remixes) - Single Fire (Price & Takis Remix) Streaming 2017 4Pro Smiler Til Fjender - Single Smiler Til Fjender Streaming 2017 666 Supa-Dupa-Fly (Remixes) - EP Supa-Dupa-Fly (Radio Version) Lets Lurk (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Streaming 2017 67 Liquez) No Hook (feat. LD, Dimzy, Asap, Monkey & Liquez) Streaming 2017 6LACK Loyal - Single Loyal Streaming 2017 8Ball Julekugler - Single Julekugler Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 Behøver ikk Behøver ikk (feat. Milo) Streaming 2017 A & MOX2 DE VED DET DE VED DET Streaming 2017 A Billion Robots This Is Melbourne - Single This Is Melbourne Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember Homesick (Special Edition) If It Means a Lot to You Streaming 2017 A Day to Remember What Separates Me from You All I Want Streaming 2017 A Flock of Seagulls Wishing: The Very Best Of I Ran Streaming 2017 A.CHAL Welcome to GAZI Round Whippin' Streaming 2017 A2M I Got Bitches - Single I Got Bitches Streaming 2017 Abbaz Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig - Single Hvor Meget Din X Ikk Er Mig Streaming 2017 Abbaz Harakat (feat. Gio) - Single Harakat (feat. Gio) Streaming 2017 ABRA Rose Fruit Streaming 2017 Abstract Im Good (feat. Roze & Drumma Battalion) Im Good (feat. Blac) Streaming 2017 Abstract Something to Write Home About I Do This (feat.