Download PDF 465.34 KB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade

Lobsters-Identification, World Distribution, and U.S. Trade AUSTIN B. WILLIAMS Introduction tons to pounds to conform with US. tinents and islands, shoal platforms, and fishery statistics). This total includes certain seamounts (Fig. 1 and 2). More Lobsters are valued throughout the clawed lobsters, spiny and flat lobsters, over, the world distribution of these world as prime seafood items wherever and squat lobsters or langostinos (Tables animals can also be divided rougWy into they are caught, sold, or consumed. 1 and 2). temperate, subtropical, and tropical Basically, three kinds are marketed for Fisheries for these animals are de temperature zones. From such partition food, the clawed lobsters (superfamily cidedly concentrated in certain areas of ing, the following facts regarding lob Nephropoidea), the squat lobsters the world because of species distribu ster fisheries emerge. (family Galatheidae), and the spiny or tion, and this can be recognized by Clawed lobster fisheries (superfamily nonclawed lobsters (superfamily noting regional and species catches. The Nephropoidea) are concentrated in the Palinuroidea) . Food and Agriculture Organization of temperate North Atlantic region, al The US. market in clawed lobsters is the United Nations (FAO) has divided though there is minor fishing for them dominated by whole living American the world into 27 major fishing areas for in cooler waters at the edge of the con lobsters, Homarus americanus, caught the purpose of reporting fishery statis tinental platform in the Gul f of Mexico, off the northeastern United States and tics. Nineteen of these are marine fish Caribbean Sea (Roe, 1966), western southeastern Canada, but certain ing areas, but lobster distribution is South Atlantic along the coast of Brazil, smaller species of clawed lobsters from restricted to only 14 of them, i.e. -

Wild Species 2010 the GENERAL STATUS of SPECIES in CANADA

Wild Species 2010 THE GENERAL STATUS OF SPECIES IN CANADA Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council National General Status Working Group This report is a product from the collaboration of all provincial and territorial governments in Canada, and of the federal government. Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council (CESCC). 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. National General Status Working Group: 302 pp. Available in French under title: Espèces sauvages 2010: La situation générale des espèces au Canada. ii Abstract Wild Species 2010 is the third report of the series after 2000 and 2005. The aim of the Wild Species series is to provide an overview on which species occur in Canada, in which provinces, territories or ocean regions they occur, and what is their status. Each species assessed in this report received a rank among the following categories: Extinct (0.2), Extirpated (0.1), At Risk (1), May Be At Risk (2), Sensitive (3), Secure (4), Undetermined (5), Not Assessed (6), Exotic (7) or Accidental (8). In the 2010 report, 11 950 species were assessed. Many taxonomic groups that were first assessed in the previous Wild Species reports were reassessed, such as vascular plants, freshwater mussels, odonates, butterflies, crayfishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds and mammals. Other taxonomic groups are assessed for the first time in the Wild Species 2010 report, namely lichens, mosses, spiders, predaceous diving beetles, ground beetles (including the reassessment of tiger beetles), lady beetles, bumblebees, black flies, horse flies, mosquitoes, and some selected macromoths. The overall results of this report show that the majority of Canada’s wild species are ranked Secure. -

GHANA STUDIES COUNCIL Newsletter Number 14 Spring 2001

GHANA STUDIES COUNCIL Newsletter Number 14 Spring 2001 are hopeful that several of these contributions will become future articles for our journal, Ghana Studies. Chair's Remarks By David Owusu-Ansah I was also very pleased to see so many of us at the Women's Caucus-sponsored panel on I extend my thanks to all of our association Yaa Asantewaa. Whilhemana Donkor members who attended the 43rd annual ASA (KNUST at Kumase), Linda Day (Hunter meeting in Nashville TN. Special thanks to College), Jean Allman (Illinois at Urbana) Akosua Adomako-Ampofo of the University and Ivor Agyeman-Dua (Journalist) presented of Ghana) and Rebecca Laumann (University on this panel. (See an update on Ivor of Memphis) for helping with the several Agyeman-Duah’s report on the Yaa travel grant applications we sent out. The Asantewaa documentary in this issue of GSC African Studies Association Visiting Scholars Newsletter.) Fund contributed to bringing Professor Francis Agbodeka’s to participate in the GSC For the November 2001 ASA conference at panel. The Spencer Foundation and Ghana Houston, TX, Ghana Studies Council has Airways were also among our supporters. submitted two panels. "Of trees, travelers and Certainly, it was a delight to have the chiefs" will be a panel discussion of recent presence of a sizeable contingent of our scholarship on the history of the timber colleagues from Ghanaian universities. industry, the current state of the tourism Professors Akilagpa Sawyerr (former Vice industry and a discussion the state of Chancellor of the University of Ghana) and chieftaincy in Ghana. Dr. Irene Odotei Agbodeka (former Dean of the Faculty of (Director, Institute of African Studies at the Arts and Letters at Cape Coast), and Dr. -

Guide to Crustacea

46 Guide to Crustacea. Order 2.—Decapoda. (Table-cases Nos. 9-16.) The gills are arranged typically in three series—podo- branchiae, arthrobranchiae, and pleurobranchiae. Only in the aberrant genus Leucifer are the gills entirely absent. The first three pairs of thoracic limbs are more or less completely modified to act as jaws (maxillipeds), while the last five form the legs. This very extensive and varied Order includes all the larger and more familiar Crustacea, such as Crabs, Lobsters, Crayfish, FIG. 30. Penaeus caramote, from the side, about half natural size. [Table-case No. 9.] Prawns, and Shrimps. From their greater size and more general interest, it is both possible and desirable to exhibit a much larger series than in the other groups of Crustacea, and in Table-cases Nos. 9 to 16 will be found representatives of all the Tribes and of the more important families composing the Order. On the system of classification adopted here, these tribes are grouped under three Sub-orders :— Sub-order 1.—Macrura. „ 2.—Anomura. ,, 3.—Brachyura. Eucarida—Decapoda. 47 SUB-ORDER I.— MACRURA. (Table-cases Nos. 9-11.) The Macrura are generally distinguished by the large size of the abdomen, which is symmetrical and not folded under the body. The front, or rostrum, is not united with the " epistome." The sixth pair of abdominal appendages (uropods) are always present, generally broad and flattened, forming with the telson, a " tail-fan." The first Tribe of the Macrura, the PENAEIDEA, consists of prawn-like animals having the first three pairs of legs usually chelate or pincer-like, and not differing greatly in size. -

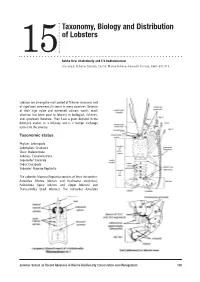

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters

Taxonomy, Biology and Distribution of Lobsters 15 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan Crustacean Fisheries Division, Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute, Kochi-682 018 Lobsters are among the most prized of fisheries resources and of significant commercial interest in many countries. Because of their high value and esteemed culinary worth, much attention has been paid to lobsters in biological, fisheries, and systematic literature. They have a great demand in the domestic market as a delicacy and is a foreign exchange earner for the country. Taxonomic status Phylum: Arthropoda Subphylum: Crustacea Class: Malacostraca Subclass: Eumalacostraca Superorder: Eucarida Order: Decapoda Suborder: Macrura Reptantia The suborder Macrura Reptantia consists of three infraorders: Astacidea (Marine lobsters and freshwater crayfishes), Palinuridea (Spiny lobsters and slipper lobsters) and Thalassinidea (mud lobsters). The infraorder Astacidea Summer School on Recent Advances in Marine Biodiversity Conservation and Management 100 Rekha Devi Chakraborty and E.V.Radhakrishnan contains three superfamilies of which only one (the Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Eryonoidea, Family Nephropoidea) is considered here. The remaining two Polychelidae superfamilies (Astacoidea and parastacoidea) contain the 1b. Third pereiopod never with a true chela,in most groups freshwater crayfishes. The superfamily Nephropoidea (40 chelae also absent from first and second pereiopods species) consists almost entirely of commercial or potentially 3a Antennal flagellum reduced to a single broad and flat commercial species. segment, similar to the other antennal segments ..... Infraorder Palinuridea, Superfamily Palinuroidea, The infraorder Palinuridea also contains three superfamilies Family Scyllaridae (Eryonoidea, Glypheoidea and Palinuroidea) all of which are 3b Antennal flagellum long, multi-articulate, flexible, whip- marine. The Eryonoidea are deepwater species of insignificant like, or more rigid commercial interest. -

Astacidea: Cambaridae): Experimental Testing of Setobranch Function

Invertebrate Biology 117(2): 129-143. © 1998 American Microscopical Society, Inc. Gill-cleaning mechanisms of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii (Astacidea: Cambaridae): experimental testing of setobranch function Raymond T. Bauer1 Department of Biology, University of Southwestern Louisiana, Lafayette, LA, 70504-2451, USA Abstract. Gills of the crayfish Procambarus clarkii are cleaned by two sets of setae which are thrust back and forth among gill filaments by feeding, locomotory, or other movements of thoracic legs. Setae with a complex, rasping microstructure arise from papillae (setobranchs.) on the third maxillipeds and pereopods 1-4, and extend up between the inner layer of arthro- branch and outer layer of podobranch gills. The lateral sides of the podobranchs, beyond the range of the setobranch setae, are penetrated by a field of setae projecting from the inner side of the gill cover. These branchiostegal setae bear digitate scale setules like those borne by the setobranch setae. Although cleaning setae act concomitantly with any type of leg movement, these animals engage in a previously unreponed behavior, "limb rocking," whose sole function appears to be gill cleaning. The effectiveness of cleaning setae was tested with experiments in which setobranch setae were removed from the branchial chamber of one side but not the other. Treated crayfishes set out in commercial ponds and a natural swamp habitat suffered heavy particulate fouling on gill filaments deprived of setobranch setae. The pattern of fouling showed that branchiostegal setae also prevented particulate fouling. However, gill-cleaning setae were not effective against bac teria] or ciliate fouling. It is concluded that molting is the only escape from epibiotic fouling in P. -

Re-Examining the Akan Gold Weight and Its Possible Reuse

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: C Sociology & Culture Volume 20 Issue 6 Version 1.0 Year 2020 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Re-Examining the Akan Gold Weight and its Possible Reuse By Andrew Richard Owusu Addo (MFA) & Ronit Akomeah Education Kwame Nkrumah University Abstract- Generally, Gold weights(called mrammou in the Akan language) are weights made of brass and used as a measuring system by the people of Akan in West Africa. This was used for weighing gold dust which was the currency until that was replaced by paper money and coins. These gold weights look like miniature models of everyday objects. In the Akan society, gold weights have played a significant part so far as the tradition and culture and the economy are concerned. The gold weights have several cultural and symbolic undertones that require a study and an understanding by modern society. Hence the study was conducted to revealed philosophical, cultural, and an outstanding value attached to the gold weights. This was attained by using qualitative research design and research instruments such as purposive and convenience sampling techniques. Interview and observation were the two main data collection tools used. However, the long hours of inquiry with key respondents in the naturalistic fieldwork which was peculiar of phenomenological study such as this aided the researcher in gaining in- depth information and understanding of what gold weights represent and its significance in the tradition and customs of the people of Akan. Keywords: gold weight, akan. -

Slipper Lobsters (Scyllaridae) Off the Southeastern Coast of Brazil: Relative Growth, Population Structure, and Reproductive

55 Abstract—The hooded slipper lobster Slipper lobsters (Scyllaridae) off the (Scyllarides deceptor) and Brazilian slipper lobster (S. brasiliensis) are southeastern coast of Brazil: relative growth, commonly caught by fishing fleets (with double-trawling and longline population structure, and reproductive biology pots and traps) off the southeastern coast of Brazil. Their reproductive Luis Felipe de Almeida Duarte (contact author)1 biology is poorly known and research 2 on these 2 species would benefit ef- Evandro Severino-Rodrigues forts in resource management. This Marcelo A. A. Pinheiro3 study characterized the population Maria A. Gasalla4 structure of these exploited species on the basis of sampling from May Email address for contact author: [email protected] 2006 to April 2007 off the coast of Santos, Brazil. Data for the abso- 1 Departamento de Zoologia 3 Laboratório de Biologia de Crustáceos lute fecundity, size at maturity in Ca[mpus de Rio Claro Grupo de Pesquisa em Biologia de Crustáceos females, reproductive period, and Universidade Estadual Paulista Ca[mpus Experimental do Litoral Paulista morphometric relationships of the Avenida 24 A, 1515 Universidade Estadual Paulista dominant species, the hooded slipper 13506-900, Rio Claro Praça Infante D. Henrique lobster, are presented. Significant São Paulo, Brazil s/n°11330-900, São Vicente differential growth was not observed 2 São Paulo, Brazil between juveniles and adults of each Instituto de Pesca 4 sex, although there was a small in- Agência Paulista de Tecnologia dos Laboratório de Ecossistemas Pesqueiros vestment of energy in the width and Agronegócios Departamento de Oceanográfico Biológica length of the abdomen in females Secretaria de Agricultura e Abastecimento Instituto Oceanográfico and in the carapace length for males Governo do Estado São Paulo Universidade de São Paulo in larger animals (>25 cm in total Avenida Bartolomeu de Gusmão, 192 Praça do Oceanográfico, 191 length [TL]). -

Shrimps, Lobsters, and Crabs of the Atlantic Coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida

SHRIMPS, LOBSTERS, AND CRABS OF THE ATLANTIC COAST OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES, MAINE TO FLORIDA AUSTIN B.WILLIAMS SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS Washington, D.C. 1984 © 1984 Smithsonian Institution. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Williams, Austin B. Shrimps, lobsters, and crabs of the Atlantic coast of the Eastern United States, Maine to Florida. Rev. ed. of: Marine decapod crustaceans of the Carolinas. 1965. Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: SI 18:2:SL8 1. Decapoda (Crustacea)—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) 2. Crustacea—Atlantic Coast (U.S.) I. Title. QL444.M33W54 1984 595.3'840974 83-600095 ISBN 0-87474-960-3 Editor: Donald C. Fisher Contents Introduction 1 History 1 Classification 2 Zoogeographic Considerations 3 Species Accounts 5 Materials Studied 8 Measurements 8 Glossary 8 Systematic and Ecological Discussion 12 Order Decapoda , 12 Key to Suborders, Infraorders, Sections, Superfamilies and Families 13 Suborder Dendrobranchiata 17 Infraorder Penaeidea 17 Superfamily Penaeoidea 17 Family Solenoceridae 17 Genus Mesopenaeiis 18 Solenocera 19 Family Penaeidae 22 Genus Penaeus 22 Metapenaeopsis 36 Parapenaeus 37 Trachypenaeus 38 Xiphopenaeus 41 Family Sicyoniidae 42 Genus Sicyonia 43 Superfamily Sergestoidea 50 Family Sergestidae 50 Genus Acetes 50 Family Luciferidae 52 Genus Lucifer 52 Suborder Pleocyemata 54 Infraorder Stenopodidea 54 Family Stenopodidae 54 Genus Stenopus 54 Infraorder Caridea 57 Superfamily Pasiphaeoidea 57 Family Pasiphaeidae 57 Genus -

Fishery Circular

NOAA TR NMFS CIRC-389 A UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Technical Report NMFS CIRC-389 PUBLICATION NOAA / V \ U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service ' ''•..,1 O' Marine Flora and Fauna of the Northeastern United States, Crustacea : Decapoda AUSTIN B.WILLIAMS SEATTLE, WA April 1974 NOAA TECHNICAL REPORTS National Marine Fisheries Service, Circulars The major responsibilities of the National Marine Fisheries Service <NMFS) are to monitor and assess the abundance and geographic distribution of fishery resources, to understand and predict fluctuations in the quantity and distribution of these resources, and to establish levels for optimum use of the resources. NMFS is also charged with the development and implementation of policies for managing national fishing grounds, development and enforcement of domestic fisheries regulations, sur^eillance of foreign fishing off United States coastal waters, and the development and enforcement of international fishery agreement and policies. NMFS also assists the fishing industry through marketing service and economic analysis programs, and mortgage insurance and vessel construction subsidies. It collects, analyzes, and publishes statistics on various phases of the industr>'. The NOAA Technical Report NMFS CIRC series continues a series that has been in existence since 1941. The Circulars are technical publications ol general interest in- tended to aid conservation and management. Publications that review in considerable detail and at a high technical level certain broad areas of research appear in this series. Technical papers originating in economics studies and from management investigations appear in the Circular series. NOAA Technical Reports NMFS CIRC are available free in limited numbers to governmental agencies, both Federal and State. -

Marine Ecology Progress Series 469:195

Vol. 469: 195–213, 2012 MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published November 26 doi: 10.3354/meps09862 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Contribution to the Theme Section ‘Effects of climate and predation on subarctic crustacean populations’ OPENPEN ACCESSCCESS Ecological role of large benthic decapods in marine ecosystems: a review Stephanie A. Boudreau*, Boris Worm Biology Department, Dalhousie University, 1355 Oxford Street, PO Box 15000, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 4R2, Canada ABSTRACT: Large benthic decapods play an increasingly important role in commercial fisheries worldwide, yet their roles in the marine ecosystem are less well understood. A synthesis of exist- ing evidence for 4 infraorders of large benthic marine decapods, Brachyura (true crabs), Anomura (king crabs), Astacidea (clawed lobsters) and Achelata (clawless lobsters), is presented here to gain insight into their ecological roles and possible ecosystem effects of decapod fisheries. The reviewed species are prey items for a wide range of invertebrates and vertebrates. They are omnivorous but prefer molluscs and crustaceans as prey. Experimental studies have shown that decapods influence the structuring of benthic habitat, occasionally playing a keystone role by sup- pressing herbivores or space competitors. Indirectly, via trophic cascades, they can contribute to the maintenance of kelp forest, marsh grass, and algal turf habitats. Changes in the abundance of their predators can strongly affect decapod population trends. Commonly documented non- consumptive interactions include interference-competition for food or shelter, as well as habitat provision for other invertebrates. Anthropogenic factors such as exploitation, the creation of pro- tected areas, and species introductions influence these ecosystem roles by decreasing or increas- ing decapod densities, often with measurable effects on prey communities. -

Estado, Paramount Chiefs Ashanti E a Construção De Uma Face De Janus Política-No Gana Pós-Colonial:Vinho Velho Em Garrafas Novas Ou Vinho Novo Em Garrafas Velhas?

Estado, Paramount Chiefs Ashanti e a Construção de uma face de Janus Política-no Gana Pós-Colonial:Vinho Velho em Garrafas Novas ou Vinho Novo em Garrafas Velhas? Vitor Alexandre Lourenço ESTADO, PAI\AMOUNT CHIEPS ASHANTI E A CONSTI\UÇAO DE UMA FACE DE JANUS POLITICA NO GANA PÓS-COLONIAL: VINHO VELHO EM GAI\1\AFAS NOVAS OU VINHO NOVO EM ~ARI\AFAS VELHASl Introdução A problemática do papel das Autoridades Tradicionais no domínio da política, e, so bretudo, do político em África, e das suas relações com os Estados, não é um assunto recente no domínio das diversas Ciências Sociais. Em termos de visibilidade académica, só a partir dos anos 80 esta problemática volta a ter a importância que teve no período que mediou entre o fim da 2. • Guerra Mundial e o início das independências africanas (Dias, 2001). De facto, nos anos 60 e 70, a problemática das relações Estado-Autoridades Tradicionais perdeu muita da sua antiga importância científica e o Estado passou a ser o centro de todas as atenções analíticas, como único e exclusivo factor politico dos países africanos recém-independentes: vide, no quadro ideológico da época, o agente social e político promotor do "desenvolvimento': da "modernização" e dos processos de "nation building" (Bayart, 1989; Chabal, 1994; Wunsch & Olowu, 1995). A partir dos anos 80, em simultâneo com a radicação da ideia do falhanço dos Estados africanos em promover um desenvolvimento equitativo e sustentável, surgiram, contudo, uma série de correntes teórico-conceptuais que buscavam contributos explicativos cen trados na diversificação das lógicas sociais em jogo no conjunto nacional, e nomeada mente nas dinâmicas da recém-gizada "sociedade civil~ Essas correntes teóricas estavam mais vocacionadas para estudarem dinâmicas sociais locais, conceptualizadas em torno das noções de "modos populares de acção política" e de "politique par le bas" (Bayart et al., 1992; Florêncio, 2006).