A Bark but No Bite: Inequality and the 2014 New Zealand General Election

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2012

A.2 Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2012 Parliamentary Service Commission Te Komihana O Te Whare Pāremata Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Schedule 2, Clause 11 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000 About the Parliamentary Service Commission The Parliamentary Service Commission (the Commission) is constituted under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. The Commission has the following functions: • to advise the Speaker on matters such as the nature and scope of the services to be provided to the House of Representatives and members of Parliament; • recommend criteria governing funding entitlements for parliamentary purposes; • recommend persons who are suitable to be members of the appropriations review committee; • consider and comment on draft reports prepared by the appropriations review committees; and • to appoint members of the Parliamentary Corporation. The Commission may also require the Speaker or General Manager of the Parliamentary Service to report on matters relating to the administration or the exercise of any function, duty, or power under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Membership The membership of the Commission is governed under sections 15-18 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Members of the Commission are: • the Speaker, who also chairs the Commission; • the Leader of the House, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the House; • the Leader of the Opposition, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the Opposition; • one member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by one or more members; and • an additional member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by 30 or more members (but does not include among its members the Speaker, the Leader of the House, or the Leader of the Opposition). -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

Aotearoa - New Zealand

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 2005 Aotearoa - New Zealand Evan S. Poata-Smith University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Poata-Smith, Evan S., Aotearoa - New Zealand 2005, 228-232. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1506 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] 228 IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2005 AOTEAROA - NEW ZEALAND “Race relations” and the place of the Treaty of Waitangi as a blueprint for nation building were very much at the forefront of the national political agenda in 2004. The broad political consensus shared by both National and Labour-led governments in New Zealand over the past decade collapsed in the wake of the soaring political popularity of Don Brash, the new leader of the National Party, the main opposition po- litical party in the New Zealand Parliament. The legitimacy of policy initiatives and programmes that specifi- cally target Mãori in order to reduce the relative socio-economic dis- parities that exist between indigenous communities and other New Zealanders, and the role of the Treaty of Waitangi in managing con- temporary relationships between indigenous communities and the Crown, have come under sustained attack. The Treaty of Waitangi under threat The underlying theme of Brash’s widely reported speech to the Orewa Rotary Club in January 2004 was the apparent “threat” that the Treaty of Waitangi settlement process represented for the future of the coun- try. -

Issue 17 2017

Shifting Stones Ruckus over Ruggers Centre Stage Catriona Britton examines the harm being done Mark Fullerton talks SKY TV’s very bad A chat with New Zealand theatre company to an historical site manners Indian Ink [1] ISSUE SEVENTEEN CONTENTS 7 NEWS 10 COMMUNITY MED STUDENTS SICK OF LOAN CAP THE LIMITS OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH Medical students aren’t getting graduation caps because of A look at how New Zealand student loan caps deals with censorship 13 LIFESTYLE 16 FEATURES SPRING AWAKENING TIT FOR TATT We’ve got tips on how to make your garden bloomin’ beautiful Olivia Stanley ponders society’s this Spring view of tattoos 31 ARTS 34 COLUMNS ONE MOVIE TO RULE THEM ALL A SHADOW OF HER FORMER SELF A definitive ranking of the LOTR and Hobbit movie Caitlin Abley has had a gutsful trilogies of Shadows cuisine New name. Same DNA. ubiq.co.nz 100% Student owned - your store on campus [3] NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND TO 4PM ON THURSDAY 24TH OF AUGUST 2017 TO VOTE GO TO: WWW.AUSA.ORG.NZ/VOTE ONLY AUSA MEMBERS CAN VOTE, HOWEVER YOU CAN SIGN UP ONLINE WHEN YOU VOTE. A POLLING BOOTH WILL BE AVAILABLE AT AUSA RECEPTION IF YOU DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO ONLINE VOTING. LIFE MEMBERS WILL NEED TO GO TO AUSA RECEPTION TO VOTE. BOB LACK AUSA RETURNING OFFICER NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE EDITORIAL 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS Giving a Shit ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND Last Monday morning, one Craccum Editor was make it into the top ten that God cast down on with deliberation and confidence. -

Protecting Our Children: Services for Children in Care

The Treasury Budget 2011 Information Release Release Document June 2011 www.treasury.govt.nz/publications/informationreleases/budget/2011 Key to sections of the Official Information Act 1982 under which information has been withheld. Certain information in this document has been withheld under one or more of the following sections of the Official Information Act, as applicable: [1] 9(2)(a) - to protect the privacy of natural persons, including deceased people [2] 9(2)(f)(iv) - to maintain the current constitutional conventions protecting the confidentiality of advice tendered by ministers and officials [3] 9(2)(g)(i) - to maintain the effective conduct of public affairs through the free and frank expression of opinions [4] 9(2)(b)(ii) - to protect the commercial position of the person who supplied the information or who is the subject of the information [5] 9(2)(k) - to prevent the disclosure of official information for improper gain or improper advantage [6] 9(2)(j) - to enable the Crown to negotiate without disadvantage or prejudice [7] 6(a) - to prevent prejudice to the security or defence of New Zealand or the international relations of the government [8] 9(2)(h) - to maintain legal professional privilege [9] 6(c) - to prevent prejudice to the maintenance of the law, including the prevention, investigation, and detection of offences, and the right to a fair trial [10] 9(2)(d) - to avoid prejudice to the substantial economic interests of New Zealand [11] 9(2)(i) - to enable the Crown to carry out commercial activities without disadvantage or prejudice. Where information has been withheld, a numbered reference to the applicable section of the Official Information Act has been made, as listed above. -

Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand

FIFTIETH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 7 August 2013 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Freepost Parliament, Adams, Hon Amy Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 6831 Minister for the Environment Wellington 6160 (04) 817 6531 Minister for Communications Selwyn National [email protected] and Information Technology Associate Minister for Canter- 829 Main South Road, Templeton (03) 344 0418/419 bury Earthquake Recovery Christchurch Fax: (03) 344 0420 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Ardern, Jacinda List Labour Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9388 Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 472 7036 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 817 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6445 Ardern, Shane Taranaki–King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Auchinvole, Chris List National (04) 817 6936 Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9392 Bakshi, Kanwaljit Singh National List Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 473 0469 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Banks, Hon John Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Leader, ACT party Wellington 6160 Minister for Regulatory Reform [email protected] (04) 817 9999 Minister for Small Business ACT Epsom Fax -

Download Download

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45(1): 14-30 Minor parties, ER policy and the 2020 election JULIENNE MOLINEAUX* and PETER SKILLING** Abstract Since New Zealand adopted the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) representation electoral system in 1996, neither of the major parties has been able to form a government without the support of one or more minor parties. Understanding the ways in which Employment Relations (ER) policy might develop after the election, thus, requires an exploration of the role of the minor parties likely to return to parliament. In this article, we offer a summary of the policy positions and priorities of the three minor parties currently in parliament (the ACT, Green and New Zealand First parties) as well as those of the Māori Party. We place this summary within a discussion of the current volatile political environment to speculate on the degree of power that these parties might have in possible governing arrangements and, therefore, on possible changes to ER regulation in the next parliamentary term. Keywords: Elections, policy, minor parties, employment relations, New Zealand politics Introduction General elections in New Zealand have been held under the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system since 1996. Under this system, parties’ share of seats in parliament broadly reflects the proportion of votes that they received, with the caveat that parties need to receive at least five per cent of the party vote or win an electorate seat in order to enter parliament. The change to the MMP system grew out of increasing public dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the previous First Past the Post (FPP) or ‘winner-take-all’ system (NZ History, 2014). -

Tuesday, October 20, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20 She Shed Support Sell-Out Mounts for Davis New Covid Strain As Deputy Pm Identified

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI TUESDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 SHE SHED SUPPORT SELL-OUT MOUNTS FOR DAVIS NEW COVID STRAIN AS DEPUTY PM IDENTIFIED PAGE 2 PAGE 3 PAGE 8 LIVID LANDSCAPE: Artist John Walsh’s painting, When decisions are made from afar, is a direct response to the forestry industry’s devastating impact on the ecology of the East Coast. SEE STORY PAGE 4 Image courtesy of John Walsh and Page Galleries. Picture by Ryan McCauley Multiple injuries from unprovoked JAIL FOR attack by drunk farmer in a fury HELLBENT on attacking a fellow farmer, who socialised in the same group, was a Gisborne man drove for 40 minutes in a fit involved in a situation with a woman. of rage fuelled by vodka, prescription drugs Morrison asked directions to the man’s and cannabis, to get to him, Gisborne District house from his neighbours and told them Court was told. they would “find out later” why he wanted to David Bruce Morrison, 47, was jailed know. The neighbours phoned ahead to warn yesterday for four years and one month, and the victim Morrison, seemingly drunk, was VIOLENT, given a three-strike warning for intentionally on his way. The victim went to his gateway to causing grievous bodily harm to the victim meet him. in an unprovoked incident about 9pm on Morrison immediately launched a vicious, October 11, 2018. prolonged, assault on the man, ultimately He pleaded guilty to the charge and an rendering him unconscious. It was extreme associated one of unlawfully possessing a violence, for which the victim subsequently firearm. -

Thank You, Maori Party! the in the United Nations Ensuring That Asks “What on That List Could Any Neither Amnesty Nor Mercy

12 Thursday 30th April, 2009 “We are by C.A. Saliya human shields by the LTTE to delay their final defeat in this bat- against...from page 8 Auckland, New Zealand tle: Ealam war IV. It is a grave mis- Thank you, take to be carried away by LTTE o the members of parliament propaganda and believe that this A lot of schools, hospitals and of the Maori Party; Hon. Dr terrorist outfit really cares about houses have been constructed and TPita Sharples—Co-Leader, the Tamil people. despite the allegation that Moscow Hon. Tariana Turia—Co-leader, Hone Harawira, the foreign was fighting against Muslims, now Hone Harawira, Te Ururoa Flavell, affairs spokesman for the Maori when Chechnya is within the Maori Party Whip, Rahui Reid Maori Party! Party, asked the New Zealand Russian federation, the biggest and Katene. Government to reinforce the mes- most beautiful mosque in Europe This is written in appreciation of sage that the Sri Lankan was constructed recently in Groznyy The Maori Party’s decision to block Government needed to exercise - equal to the best mosques in Saudi the motion expressing concern restraint against the Tamil Tigers Arabia. So life is quite normal there. about the Sri Lankan “humanitari- which is now in its last enclave. This is the way we hope the govern- an situation”; that is, the fighting The report that “Waiariki MP Te ment in Sri Lanka will also go, against LTTE terrorists by the Ururoa Flavell loudly objected to because it is most important to find Government forces of Sri Lanka. -

European Parliament DANZ Report

European Parliament Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) visit Auckland and Wellington 23-26 February 2020 Report on the European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) visit 23-26 February 2020 Background The European Parliament’s Delegation for relations with Australia and New Zealand (DANZ) and the New Zealand Parliament have regular exchange meetings. This year it was the turn of DANZ to visit New Zealand for the 24th Inter-parliamentary meeting. As the visit was on a non-sitting week for the New Zealand Parliament, this meeting was held in Auckland to enable easier attendance for New Zealand parliamentarians. This was followed by meetings in Wellington, including with the Speaker of the House of Representatives, three New Zealand Cabinet Ministers and the New Zealand Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade. DANZ’s visit this year was comprised of a larger delegation than usual. Eight members of the European Parliament (MEPs) came to New Zealand, including a Vice President. The members were from five of the six main political groups in the European Parliament – the European People's Party (Christian Democrats), the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament, Renew Europe, the Greens/European Free Alliance and the European Conservatives and Reformists. 1 The DANZ visit was led by Chairperson, Ulrike Müller MEP, who also led the previous delegation to New Zealand in 2018.2 Inter-parliamentary meeting The 2020 meeting was held on Monday 24th February. The New Zealand Members of Parliament who attended are listed at the end of this report. -

Form to Email

To: Bee: Subject: NZ Superannuation Fund enquiry Date: Thursday, 6 December 2012 4: 10:53 PM Attachments: Guardians Final response to Israel petition.pdf Dea . , Thank you for your email via our website. Your comments have been noted and passed on to our Chairman and CEO. I have attached a copy of the Guardians' response to the petition and FYI the Committee's report is available at http://www parliament nz/NR/rdonlyres/60EEA9A7-4218-473F-BCFF- 2347E483EBEB/244228/DBSCH $CR 5595 Petjtjon2008143ofLojsGrjffithsand38 pdf We expect to be in a position to respond more fully to your email next week. In future, please feel free to contact me directly on the details below. Best regards Catherine Etheredge Catherine Etheredge Head of Communications DDI: Mobile: Email: A Great Team Building the Best Portfolio PO Box 106 607, Auckland 1143, New Zealand Level 12, Zurich House, 21 Queen Street, Auckland 1010, New Zealand Office: +64 9 300 6980 I Fax: +64 9 300 6981 I Web: www.nzsuperfund.co.nz From: formmail@digitaistream co oz [mailto·formmail@digitaistream co oz] Sent: Thursday, 29 November 2012 2:53 p.m. To: Enquiries Subject: Query from website Form to Email Form to email received the following values Name - Company Optional Phone email from Contact Email me by Website feedback Responsible Investment Query re Responsible Investment Dear NZ Superfund, Please send this message to the Board or at least to the Chair. In September 2011,ex-MP Keith Locke presented a petition to Parliament, ■■■■■I asking for Parliament to ask the Guardians of Superfund to divest ow ve een to t at t e ommerce ommIttee as reJecte e pe 1 I0n. -

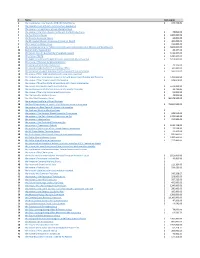

Working Groups and Reviews

# Name Cost approx 1 the investigation into Waikato DHB CEO Nigel Murray $ 174,466.81 2 the review to look at how to control prison population 3 the review of six contracts for new charter schools 4 the review of the Metro Sports Facility and the Multi Use Arena $ 78,893.00 5 the Tax Working Group $ 4,000,000.00 6 the Housing Stocktake Report $ 34,000.00 7 the Ministerial Advisory Group established for Health $ 300,000.00 8 the irrigation funding review $ 110,000.00 9 the investigation into the NZ Defence Force water contamination at Ohakea and Woodbourne $ 3,800,000.00 10 Darroch Ball's KiwiFund Bill $ 42,377.00 11 the Inquiry into the Auckland Fuel Supply Disruption $ 1,128,000.00 12 the review of NCEA $ 4,285,000.00 13 the Digital Economy and Digital Inclusion Ministerial Advisory Group $ 2,313,000.00 14 the review of the kauri dieback programme 15 the Independent Climate Commission $ 25,126.00 16 the now disestablished Chief Technology Officer $ 500,000.00 17 the Independent Expert Advisory Panel's review of the Reserve Bank $ 169,923.00 18 the review of the Credit Contracts and Consumer Finance Act 19 the Productivity Commission's inquiry into Local Government funding and financing $ 2,200,000.00 20 the review of the Primary Growth Partnership $ 142,042.00 21 the review of how the Waste Minimisation Act is being implemented 22 the Inquiry into Mental Health and Addiction $ 6,521,000.00 23 the reconvened Joint Working Group on Pay Equity Principles $ 26,423.85 24 the review of the Local Government Commission $ 91,000.00 25 the Film