Māori Economic Development Taskforce

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021 Attention: Television New Zealand Contact: (04) 913-3000 Release date: 27 May 2021 Level One 46 Sale Street, Auckland CBD PO Box 33690 Takapuna Auckland 0740 Ph: (09) 919-9200 Level 9, Legal House 101 Lambton Quay PO Box 3622, Wellington 6011 Ph: (04) 913-3000 www.colmarbrunton.co.nz Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology summary ................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of results .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Key political events ................................................................ .......................................................................... 4 Question order and wording ............................................................................................................................ 5 Party vote ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Preferred Prime Minister ................................................................................................................................. 8 Public Sector wage freeze ............................................................................................................................. -

Fiftieth Parliament of New Zealand

FIFTIETH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 7 August 2013 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Freepost Parliament, Adams, Hon Amy Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 6831 Minister for the Environment Wellington 6160 (04) 817 6531 Minister for Communications Selwyn National [email protected] and Information Technology Associate Minister for Canter- 829 Main South Road, Templeton (03) 344 0418/419 bury Earthquake Recovery Christchurch Fax: (03) 344 0420 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Ardern, Jacinda List Labour Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9388 Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 472 7036 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 817 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6445 Ardern, Shane Taranaki–King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Auchinvole, Chris List National (04) 817 6936 Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament, Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings (04) 817 9392 Bakshi, Kanwaljit Singh National List Wellington 6160 Fax: (04) 473 0469 [email protected] Freepost Parliament Banks, Hon John Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Leader, ACT party Wellington 6160 Minister for Regulatory Reform [email protected] (04) 817 9999 Minister for Small Business ACT Epsom Fax -

Download Download

New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 45(1): 14-30 Minor parties, ER policy and the 2020 election JULIENNE MOLINEAUX* and PETER SKILLING** Abstract Since New Zealand adopted the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) representation electoral system in 1996, neither of the major parties has been able to form a government without the support of one or more minor parties. Understanding the ways in which Employment Relations (ER) policy might develop after the election, thus, requires an exploration of the role of the minor parties likely to return to parliament. In this article, we offer a summary of the policy positions and priorities of the three minor parties currently in parliament (the ACT, Green and New Zealand First parties) as well as those of the Māori Party. We place this summary within a discussion of the current volatile political environment to speculate on the degree of power that these parties might have in possible governing arrangements and, therefore, on possible changes to ER regulation in the next parliamentary term. Keywords: Elections, policy, minor parties, employment relations, New Zealand politics Introduction General elections in New Zealand have been held under the Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) system since 1996. Under this system, parties’ share of seats in parliament broadly reflects the proportion of votes that they received, with the caveat that parties need to receive at least five per cent of the party vote or win an electorate seat in order to enter parliament. The change to the MMP system grew out of increasing public dissatisfaction with certain aspects of the previous First Past the Post (FPP) or ‘winner-take-all’ system (NZ History, 2014). -

Thank You, Maori Party! the in the United Nations Ensuring That Asks “What on That List Could Any Neither Amnesty Nor Mercy

12 Thursday 30th April, 2009 “We are by C.A. Saliya human shields by the LTTE to delay their final defeat in this bat- against...from page 8 Auckland, New Zealand tle: Ealam war IV. It is a grave mis- Thank you, take to be carried away by LTTE o the members of parliament propaganda and believe that this A lot of schools, hospitals and of the Maori Party; Hon. Dr terrorist outfit really cares about houses have been constructed and TPita Sharples—Co-Leader, the Tamil people. despite the allegation that Moscow Hon. Tariana Turia—Co-leader, Hone Harawira, the foreign was fighting against Muslims, now Hone Harawira, Te Ururoa Flavell, affairs spokesman for the Maori when Chechnya is within the Maori Party Whip, Rahui Reid Maori Party! Party, asked the New Zealand Russian federation, the biggest and Katene. Government to reinforce the mes- most beautiful mosque in Europe This is written in appreciation of sage that the Sri Lankan was constructed recently in Groznyy The Maori Party’s decision to block Government needed to exercise - equal to the best mosques in Saudi the motion expressing concern restraint against the Tamil Tigers Arabia. So life is quite normal there. about the Sri Lankan “humanitari- which is now in its last enclave. This is the way we hope the govern- an situation”; that is, the fighting The report that “Waiariki MP Te ment in Sri Lanka will also go, against LTTE terrorists by the Ururoa Flavell loudly objected to because it is most important to find Government forces of Sri Lanka. -

Rawiri Taonui: Partnership Gives Reason for Hope

Rawiri Taonui: Partnership gives reason for hope John Key (pictured here at Waitangi) enjoys an approval rating among Maori of 47 per cent. Photo / Brett Phibbs In recent weeks the descendants of the Maori prophet Wiremu Tahupotiki Ratana gave their blessing to the one-year-old National-Maori Party partnership. Prime Minister John Key's no-baggage, no-nonsense, straight-talking "let's work together" style is a race relations revelation. He knows what matters and what doesn't (flying two flags is not a drama), and where the boundaries lie - "let the Maori Party deal with Hone Harawira, he is their member". The twin pillars of the Maori Party leadership, Tariana Turia and Pita Sharples, have also been important. Dignified, thoughtful and strong, they are the best Maori political leaders since Princess Te Puea and Apirana Ngata. This triumvirate knows that working together is about trust, keeping things simple and the freedom to disagree. The win over Labour at Ratana belies deeper waters ahead. Waitangi Day looms large with several in Ngapuhi set to fly the St George Cross of the Confederation ensign instead of the newly chosen Rangatiratanga flag. There is room for embarrassment as the debate plays out on Hone Heke Harawira's home turf. Budget 2010 signals the roll out of the whanau ora, with some estimating up to $1 billion in resources devolved to Maori social service providers. Modelled on successful initiatives in health - where the increase of Maori providers from 0 to 275 in 25 years has had real impact - they understand issues better, know the communities, and don't suffer the ingrained prejudices built up over multiple generations in mainstream institutions. -

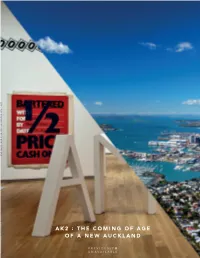

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach. -

Effecting Change Through Electoral Politics: Cultural Identity and the Mäori Franchise

EFFECTING CHANGE THROUGH ELECTORAL POLITICS: CULTURAL IDENTITY AND THE MÄORI FRANCHISE ANN SULLIVAN University of Auckland The indigenous peoples of New Zealand signed the Treaty of Waitangi with British colonisers in 1840. The colonisers then used the Treaty to usurp Mäori sovereignty and Mäori ownership of lands, fisheries, forests and other natural resources. Article 3 of the Treaty, however, guaranteed Mäori the same rights and privileges as British subjects, including the franchise. Initially, eligibility rights pertaining to the franchise effectively excluded Mäori participation, but in 1867 it became politically expedient to provide Mäori with separate parliamentary representation, which has been retained ever since. Mäori successfully used the franchise to bring about beneficial welfare changes after the depression years of the 1930s; however, but it was not until changes were made to the electoral system in 1993 that its potential as a tool for increased access to political power was realised. Today all political parties are courting the Mäori vote and Mäori are using the electoral system to further their self-determining goals of tino rangatiratanga (Mäori control over their cultural, social and economic development). This essay discusses how Mäori have used the Mäori franchise in their struggle to hold on to their culture and their language, and in their pursuit of economic development. EQUAL CITIZENSHIP VS FRANCHISE INEQUALITIES The New Zealand Constitution Act 1852 provided the franchise to all males (including Mäori) over the age of 21 years provided they were registered individual property owners (Orange 1987:137). In reality few Mäori males were eligible to vote as most Mäori land was communally owned and not registered in individual titles. -

Friday, July 10, 2020 Home-Delivered $1.90, Retail $2.20

TE NUPEPA O TE TAIRAWHITI FRIDAY, JULY 10, 2020 HOME-DELIVERED $1.90, RETAIL $2.20 LANDFILL BREACH STAR PAGES 3, 6-8, 10 ANOTHER WAKE-UP CALL OF GLEE COVID-19NEW 12-13, 20 PAGE 5 MISSING, • PBL Helen Clark heading Covid-19 response panel PRESUMED • Police to be posted at all managed isolation facilities DROWNED •PAGE Poor 3 response in US blamed on ‘anti-science bias’ • Covid-19 worldwide cases passes 12 million PAGE 12 SNOWDUST: Daytime maximum temperatures across Tairawhiti struggled to reach 11 degrees yesterday as the cold southerly brought a sprinkling of snow to the top of Mount Hikurangi — captured on camera by Sam Spencer. “We’re well and truly into the midst of winter now and yesterday sure would have felt like it,” said a MetService forecaster. “The dewpoint temperature (measure of moisture in air) was around zero degrees when the maximum air temperature was recorded. “The average daily maximum for Gisborne in July is around 15 degrees. “So it’s colder than average but it will need to drop a few more degrees to get into record books.” The district avoided the forecast frost overnight due to cloud cover, but MetService predicts 1 degree at Gisborne Airport tomorrow morning. by Matai O’Connor British High Commissioner to recovery,” she said. “Individuals New Zealand Laura Clarke, and organisations across TOITU Tairawhiti, a and Te Whanau o Waipareira Tairawhiti, including iwi, all collective of local iwi, have chief executive John Tamihere did a great job. organised a two-day summit to and Director-General of Health “We want to benchmark and reflect on the region’s response Dr Ashley Bloomfield. -

The Ministry of Public Input

The Ministry of Public Input: Report and Recommendations for Practice By Associate Professor Jennifer Lees-Marshment The University of Auckland, New Zealand August 2014 www.lees-marshment.org [email protected] Executive Summary Political leadership is undergoing a profound evolution that changes the role that politicians and the public play in decision making in democracy. Rather than simply waiting for voters to exercise their judgement in elections, political elites now use an increasingly varied range of public input mechanisms including consultation, deliberation, informal meetings, travels out in the field, visits to the frontline and market research to obtain feedback before and after they are elected. Whilst politicians have always solicited public opinion in one form or another, the nature, scale, and purpose of mechanisms that seek citizen involvement in policy making are becoming more diversified and extensive. Government ministers collect different forms of public input at all levels of government, across departments and through their own offices at all stages of the policy process. This expansion and diversification of public input informs and influences our leaders’ decisions, and thus has the potential to strengthen citizen voices within the political system, improve policy outcomes and enhance democracy. However current practice wastes both resources and the hope that public input can enrich democracy. If all the individual public input activities government currently engages in were collated and added up it would demonstrate that a vast amount of money and resources is already spent seeking views from outside government. But it often goes unseen, is uncoordinated, dispersed and unchecked. We need to find a way to ensure this money is spent much more effectively within the realities of government and leadership. -

Note to All Media: EMBARGOED Until 11 Am Sunday 12 October 2008 MARAE-DIGIPOLL SURVEY TAMAKI MAKAURAU ELECTORATE

11 October 2008 Marae TVNZ Maori Programmes Note to all Media: EMBARGOED until 11 am Sunday 12 October 2008 MARAE-DIGIPOLL SURVEY TAMAKI MAKAURAU ELECTORATE TVNZ Maori Programmes production, Marae recently commissioned Hamilton polls analysts DigiPoll to survey voters registered in the Maori electorate of Tamaki Makaurau. The survey was conducted between 15 September and 7 October 2008. 400 voters on the Tamaki Makaurau were surveyed. The margin of error is +/- 4.9%. Contact: Derek Kotuku Wooster Producer / Director Marae TVNZ Maori Programmes 09 916 7971 021 654 044 [email protected] Marae – DigiPoll September/October 2008 Tamaki Makaurau Electorate Q1. Party Vote If an election was held today which political party would you vote for? Labour 37.5% Maori Party 41.2% NZ First 7.3% National 5.9% Greens 4.0% Others 4.1% Q2. Electorate Vote Now taking your second vote under MMP which is for the Maori Seat, which candiate would you give your seat vote to? Louisa Wall of the Labour Party 13.5% Dr Pita Sharples of the Maori Party 77.4% Mikaere Curtis of the Green Party 6.5% Other 2.6% Q3. Of all political leaders in New Zealand, who is your preferred Prime Minister? Helen CLARK 39.0% Winston PETERS 10.2% Pita SHARPLES 7.2% John KEY 6.7% Tariana TURIA 5.9% Parekura Horomia 1.9% Others 5.3% None 9.4% Don’t know 14.4% Q4. Do you think the government is heading in the right direction? Yes 46.5% No 39.7% Don’t Know 13.8% Q5. -

Do We Need Kiwi Lessons in Biculturalism?

Do We Need Kiwi Lessons in Biculturalism? Considering the Usefulness of Aotearoa/New Zealand’sPakehā ̄Identity in Re-Articulating Indigenous Settler Relations in Canada DAVID B. MACDONALD University of Guelph Narratives of “métissage” (Saul, 2008), “settler” (Regan, 2010; Barker and Lowman, 2014) “treaty people” (Epp, 2008; Erasmus, 2011) and now a focus on completing the “unfinished business of Confederation” (Roman, 2015) reinforce the view that the government is embarking on a new polit- ical project of Indigenous recognition, inclusion and partnership. Yet recon- ciliation is a contested concept, especially since we are only now dealing with the inter-generational and traumatic legacies of the Indian residential schools, missing and murdered Indigenous women and a long history of (at least) cultural genocide. Further, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, with its focus on Indigenous self-determi- nation, has yet to be implemented in Canadian law. Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) presented over 94 recommendations and sub-recommendations to consider, outlining a long-term process of cre- ating positive relationships and helping to restore the lands, languages, David MacDonald, Department of Political Science, University of Guelph, 50 Stone Road East, Guelph ON, N1G 2W1, email: [email protected] Nga mihi nui, nya: weh,̨ kinana’skomitina’wa’w, miigwech, thank you, to Dana Wensley, Rick Hill, Paulette Regan, Dawnis Kennedy, Malissa Bryan, Sheryl Lightfoot, Kiera Ladner, Pat Case, Malinda Smith, Brian Budd, Moana Jackson, Margaret Mutu, Paul Spoonley, Stephen May, Robert Joseph, Dame Claudia Orange, Chris Finlayson, Makere Stewart Harawira, Hone Harawira, Te Ururoa Flavell, Tā Pita Sharples, Joris De Bres, Sir Anand Satyananand, Phil Goff, Shane Jones, Ashraf Choudhary, Andrew Butcher, Hekia Parata, Judith Collins, Kanwaljit Bakshi, Chris Laidlaw, Rajen Prasad, Graham White, and three anonymous reviewers. -

Members of the Executive Expenses

MEMBERS OF THE EXECUTIVE EXPENSES DISCLOSURE FROM 1 JULY 2013 TO 30 SEPTEMBER 2013 Party Minister Wellington Out of Domestic Surface Sub Total Official Accommodation Wellington Air Travel Travel Internal Cabinet (Ministers only) Travel (Ministers (Ministers, Costs Approved Expenses only) Spouse and International (Ministers Staff) Travel (A) only) Act John Banks 10,069 139 5,890 11,060 27,157 - Total Act 10,069 139 5,890 11,060 27,157 - Maori Pita Sharples 8,055 262 9,988 44,345 62,649 18,499 Maori Tariana Turia 10,069 3,001 11,017 36,730 60,816 7,859 Total Maori 18,123 3,263 21,005 81,075 123,466 26,358 Allocated Crown National John Key 1,612 8,609 33,067 43,288 42,224 Owned Property Allocated Crown National Bill English 1,051 9,031 20,026 30,108 37,436 Owned Property Gerry Allocated Dept National Brownlee Owned Property 631 7,121 18,762 26,513 - National Steven Joyce 10,069 613 12,814 15,266 38,762 10,937 National Judith Collins 10,069 411 6,055 38,110 54,644 46,801 National Tony Ryall 10,069 2,058 9,876 12,072 34,075 34,055 National Hekia Parata N/A 2,447 7,138 21,059 30,64447,453 Chris National Finlayson - 1,6128,609 33,067 43,28842,224 National Paula Bennett 10,069 813 8,634 22,075 41,591 13,481 Jonathan National Coleman 10,069 510 7,821 19,456 37,85640,727 Murray National McCully 8,055 - 4,66722,855 35,577212,609 National Anne Tolley 10,069 2,058 9,876 12,072 34,075 34,055 National Nick Smith 10,069 613 12,814 15,266 38,762 10,937 National Tim Groser 10,069 883 4,343 16,317 31,612 151,246 National Amy Adams 10,069 1,170 10,119 20,557