Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 22 – 26 May 2021 Attention: Television New Zealand Contact: (04) 913-3000 Release date: 27 May 2021 Level One 46 Sale Street, Auckland CBD PO Box 33690 Takapuna Auckland 0740 Ph: (09) 919-9200 Level 9, Legal House 101 Lambton Quay PO Box 3622, Wellington 6011 Ph: (04) 913-3000 www.colmarbrunton.co.nz Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology summary ................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of results .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Key political events ................................................................ .......................................................................... 4 Question order and wording ............................................................................................................................ 5 Party vote ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Preferred Prime Minister ................................................................................................................................. 8 Public Sector wage freeze ............................................................................................................................. -

Leading the Way Fight Night Rescheduled

Thursday, July 9, 2020 Since Sept 27, 1879 Retail $2.20 Home delivered from $1.40 THE INDEPENDENT VOICE OF MID CANTERBURY Leading Fight Night the way rescheduled P3 P16 National MPs (from left): Andrew Falloon, Gerry Brownlee, party leader Todd Muller and Selwyn candidate Nicola Grigg at the announcement of the party’s com- mitment to a four-lane highway between Ashburton and Christchurch. PHOTO HEATHER MACKENZIE 080720-HM-0055 Four-lane commitment BY JAIME PITT-MACKAY a whirlwind visit through Can- tha-Southland MP Hamish four lanes of highway, it’s fantas- suring that it is all sorted so we [email protected] terbury on Wednesday, ahead Walker. tic,” he quipped. can construct it,” he said. National leader Todd Muller has of a public meeting at the Hotel After an extended period of Muller confirmed the road will “We have a fantastic track re- sent a clear message to voters Ashburton. questions about the scandal, be 60kms long, between Ash- cord with infrastructure projects ahead of the September elec- The announcement was made which has resulted in Walker burton and Christchurch, and with the roads of national signif- tion; vote me into Government, to both local and national me- announcing he won’t stand in would cost $1.5 billion. It would icance. and I will build you 60km of dia, but was somewhat over- this year’s election, Muller was also include second bridges be- four-lane highway between Ash- shadowed by the controversy looking to talk more about the ing built on the Ashburton, Sel- burton and Christchurch. -

Annual Report for the Year Ended 30 June 2012

A.2 Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2012 Parliamentary Service Commission Te Komihana O Te Whare Pāremata Presented to the House of Representatives pursuant to Schedule 2, Clause 11 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000 About the Parliamentary Service Commission The Parliamentary Service Commission (the Commission) is constituted under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. The Commission has the following functions: • to advise the Speaker on matters such as the nature and scope of the services to be provided to the House of Representatives and members of Parliament; • recommend criteria governing funding entitlements for parliamentary purposes; • recommend persons who are suitable to be members of the appropriations review committee; • consider and comment on draft reports prepared by the appropriations review committees; and • to appoint members of the Parliamentary Corporation. The Commission may also require the Speaker or General Manager of the Parliamentary Service to report on matters relating to the administration or the exercise of any function, duty, or power under the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Membership The membership of the Commission is governed under sections 15-18 of the Parliamentary Service Act 2000. Members of the Commission are: • the Speaker, who also chairs the Commission; • the Leader of the House, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the House; • the Leader of the Opposition, or a member of Parliament nominated by the Leader of the Opposition; • one member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by one or more members; and • an additional member for each recognised party that is represented in the House by 30 or more members (but does not include among its members the Speaker, the Leader of the House, or the Leader of the Opposition). -

Todd Muller Mp for Bay of Plenty

TODD MULLER MP FOR BAY OF PLENTY Community Newsletter | Autumn 2021 I often wonder as I sit in the dark of our Mount It is always risky to call out individuals but I have Maunganui dawn service listening to the waves four names I want to acknowledge: fold gently upon each other whether I would Bryce McFall and Amanda Lowry whose work have thrown myself into the water like those with our disabled athletes to help them be the landing in Gallipoli or Normandy. best they can be is just stunning. Whether I would have driven on into the desert Andrew Hitchfieldand Jim Pearson, from valleys of the Middle East and North Africa or Papamoa Surf Lifesaving Club who have worked slashed through impenetrable jungles of Asia. In for years and years to get our new surf club my bravest moments I tell myself I would have built. and so would my friends, but if I am honest I find their bravery and courage daunting beyond These four will immediately say they are part of measure. I am particularly moved by the humility a much wider team, which of course is true, but of our service men and women. someone has to lead, someone has to serve, and in these four we have great community To those who think that the greatest (WW2) examples. generation can’t be replicated, I can give you confidence that our current service women and We live in a remarkable community at a men are exemplary. In 2017 I was very privileged profoundly challenging time. -

National Spokespeople Chart (190118)

LEADER DEPUTY LEADER SIMON BRIDGES PAULA BENNETT AMY ADAMS KANWAL SINGH BAKSHI MAGGIE BARRY ANDREW BAYLY DAVID BENNETT DAN BIDOIS CHRIS BISHOP SIMEON BROWN Tauranga • National Upper Harbour Selwyn • Finance List MP • Internal Affairs North Shore • Seniors Hunua • Building and Hamilton East Northcote Hutt South Pakuranga Security and Social Investment & Social Shadow Attorney-General Assoc. Justice Veterans • Assoc. Health Construction • Revenue Corrections Assoc. Workplace Relations Police • Youth Assoc. Education • Assoc. Tertiary Intelligence Services • Drug Reform • Women Assoc. Finance Land Information and Safety Education, Skills & Employment Assoc. Infrastructure GERRY BROWNLEE DAVID CARTER JUDITH COLLINS JACQUI DEAN MATT DOOCEY SARAH DOWIE ANDREW FALLOON PAUL GOLDSMITH NATHAN GUY JO HAYES Ilam • Shadow Leader of List MP Papakura • Housing & Urban Waitaki Waimakariri Invercargill Rangitata • Regional List MP • Economic & Regional Otaki • Agriculture List MP • Whānau Ora the House • GCSB • NZSIS State-Owned Enterprises Development • Infrastructure Local Government Mental Health Conservation Development (South Island) Development • Transport Biosecurity • Food Safety Māori Education America’s Cup Planning (RMA Reform) Small Business Junior Whip Assoc. Arts, Culture & Heritage HARETE HIPANGO BRETT HUDSON NIKKI KAYE MATT KING NUK KORAKO BARBARA KURIGER DENISE LEE MELISSA LEE AGNES LOHENI TIM MACINDOE Whanganui List MP • Commerce & Auckland Central Northland List MP • Māori Development Taranaki - King Country Maungakiekie List MP • Broadcasting, -

'About Turn': an Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's

Newcastle University e-prints Date deposited: 2nd May 2013 Version of file: Author final Peer Review Status: Peer reviewed Citation for item: Reardon J, Gray TS. About Turn: An Analysis of the Causes of the New Zealand Labour Party's Adoption of Neo-Liberal Policies 1984-1990. Political Quarterly 2007, 78(3), 447-455. Further information on publisher website: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com Publisher’s copyright statement: The definitive version is available at http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-923X.2007.00872.x Always use the definitive version when citing. Use Policy: The full-text may be used and/or reproduced and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not for profit purposes provided that: A full bibliographic reference is made to the original source A link is made to the metadata record in Newcastle E-prints The full text is not changed in any way. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Robinson Library, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Newcastle upon Tyne. NE1 7RU. Tel. 0191 222 6000 ‘About turn’: an analysis of the causes of the New Zealand Labour Party’s adoption of neo- liberal economic policies 1984-1990 John Reardon and Tim Gray School of Geography, Politics and Sociology Newcastle University Abstract This is the inside story of one of the most extraordinary about-turns in policy-making undertaken by a democratically elected political party. -

Issue 17 2017

Shifting Stones Ruckus over Ruggers Centre Stage Catriona Britton examines the harm being done Mark Fullerton talks SKY TV’s very bad A chat with New Zealand theatre company to an historical site manners Indian Ink [1] ISSUE SEVENTEEN CONTENTS 7 NEWS 10 COMMUNITY MED STUDENTS SICK OF LOAN CAP THE LIMITS OF FREEDOM OF SPEECH Medical students aren’t getting graduation caps because of A look at how New Zealand student loan caps deals with censorship 13 LIFESTYLE 16 FEATURES SPRING AWAKENING TIT FOR TATT We’ve got tips on how to make your garden bloomin’ beautiful Olivia Stanley ponders society’s this Spring view of tattoos 31 ARTS 34 COLUMNS ONE MOVIE TO RULE THEM ALL A SHADOW OF HER FORMER SELF A definitive ranking of the LOTR and Hobbit movie Caitlin Abley has had a gutsful trilogies of Shadows cuisine New name. Same DNA. ubiq.co.nz 100% Student owned - your store on campus [3] NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND TO 4PM ON THURSDAY 24TH OF AUGUST 2017 TO VOTE GO TO: WWW.AUSA.ORG.NZ/VOTE ONLY AUSA MEMBERS CAN VOTE, HOWEVER YOU CAN SIGN UP ONLINE WHEN YOU VOTE. A POLLING BOOTH WILL BE AVAILABLE AT AUSA RECEPTION IF YOU DO NOT HAVE ACCESS TO ONLINE VOTING. LIFE MEMBERS WILL NEED TO GO TO AUSA RECEPTION TO VOTE. BOB LACK AUSA RETURNING OFFICER NOTICE OF POLLING TIMES FOR THE EDITORIAL 2018 AUSA EXECUTIVE Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti & 2017 ENVIRONMENTAL AFFAIRS OFFICER ELECTIONS Giving a Shit ONLINE ELECTIONS WILL BE HELD FROM 9AM ON TUESDAY 22ND Last Monday morning, one Craccum Editor was make it into the top ten that God cast down on with deliberation and confidence. -

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 9 – 13 March 2021

1 NEWS Colmar Brunton Poll 9 – 13 March 2021 Attention: Television New Zealand Contact: (04) 913-3000 Release date: 15 March 2021 Level One 46 Sale Street, Auckland CBD PO Box 33690 Takapuna Auckland 0740 Ph: (09) 919-9200 Level 9, Legal House 101 Lambton Quay PO Box 3622, Wellington 6011 Ph: (04) 913-3000 www.colmarbrunton.co.nz Contents Contents .......................................................................................................................................................... 1 Methodology summary ................................................................................................................................... 2 Summary of results .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Key political events ................................................................ .......................................................................... 4 Question order and wording ............................................................................................................................ 5 Party vote ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 Preferred Prime Minister ................................................................................................................................. 8 Economic outlook ......................................................................................................................................... -

Māori Economic Development Taskforce

IWI Infrastructure and Investment Māori Economic Development Taskforce May 2010 E te kāhui tipua, Nei rā te reo o Aoraki maunga e topa atu ana ki a koutou hai mihi. E kore rawa tā Tahu Pōtiki puna whakamihi e mimiti noa. Ko koutou tērā e whakaheke mōtuhi ana kia whai oranga ai te iwi Māori. Kua roa nei koutou e whakaporo riaka ana kia ea ai ngā wawata o ō koutou ake whānau, o ō koutou ake hapū, o ō koutou ake iwi. Ko ngā puapua ki aromea kua tutuki i a koutou. Nō reira, kei te mihi. Eke panuku, eke Tangaroa. Nā koutou te reo karanga, nā mātou ngā kupu tautoko kia okea ururoatia ngā taunāhua o te iwi Māori. E ai ki te whakataukī a ō tātou nei tūpuna, ki te kotahi te kākaho ka whati, ki te kāpuia te kākaho e kore e whati. Nō reira e aku rangatira, nei rā te karanga o Aoraki maunga ki ngā tōpito katoa o te motu kia karapinepine mai i raro i te whakaaro kotahi. Nō reira e aku manukura, nau mai tauti mai ki raro i tōna poho hai wānanga, hai kōrerorero, hai ara whakamua mō tātou, ā, mō kā uri ā muri ake nei. Tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou, tēnā koutou katoa ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS These materials have been prepared by Mark Solomon under the Māori Economic Taskforce. The Māori Economic Taskforce was established in March 2009 as a result of the Māori Economic Summit and is a key initiative for the enhancement of Māori economic prosperity. On 28 January 2009, the Minister of Māori Aff airs held an Economic Summit to canvass ideas and potential initiatives to ensure Māori could both mitigate the eff ects of the economic downturn and position themselves to reap the benefi ts of economic recovery. -

A Politics and the Campaign

Notes Resources Processor Time 00:00:00.24 Elapsed Time 00:00:00.00 Frequency Table jinterest A1: how interested in politics Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Very interested 412 16.7 16.7 16.7 Fairly interested 1157 46.8 47.0 63.7 Slightly interested 769 31.1 31.2 94.9 Not at all interested 125 5.0 5.1 100.0 Total 2463 99.5 100.0 Missing System 12 .5 Total 2475 100.0 jrefbefore A2: knowledge of referendum before the fact Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Yes 2192 88.6 89.3 89.3 No 167 6.7 6.8 96.1 Don't know 95 3.8 3.9 100.0 Total 2453 99.1 100.0 Missing System 22 .9 Total 2475 100.0 Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid Yes 2041 82.5 83.3 83.3 No 300 12.1 12.2 95.6 Don't know 108 4.4 4.4 100.0 Total 2449 99.0 100.0 Missing System 26 1.0 Total 2475 100.0 jintnt_work A4: access to the Internet at work Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 1444 58.3 58.3 58.3 Internet access at work 1031 41.7 41.7 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_home A4: access to the Internet at home Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 524 21.2 21.2 21.2 Internet access at home 1951 78.8 78.8 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 Page 3 jintnt_mob A4: access to the Internet on a mobile device Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 1843 74.5 74.5 74.5 632 25.5 25.5 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_else A4: access to the Internet somewhere else Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 2345 94.7 94.7 94.7 130 5.3 5.3 100.0 Total 2475 100.0 100.0 jintnt_none A4: no access to the Internet Frequency Percent Valid Percent Valid 0 2096 84.7 84.7 84.7 No Internet access -

Where Our Voices Sound Risky Business See More Seymour

Where Our Voices Sound Risky Business See More Seymour Helen Yeung chats with Mermaidens (not the Jordan Margetts takes on Facebook, the Herald Meg Williams delves deep on a dinner date with Harry Potter kind) and that office sex scandal the ACT Party Leader [1] ISSUE ELEVEN CONTENTS 9 10 NEWS COMMUNITY NORTHLAND GRAVE A CHOICE VOICE ROBBING? An interview with the strong Unfortunately for Split Enz, it women behind Shakti Youth appears that history does repeat 13 14 LIFESTYLE FEATURES SHAKEN UP MORE POWER TO THE PUSSY Milkshake hotspots to bring more than just boys to your A look into the growing yard feminist porn industry 28 36 ARTS COLUMNS WRITERS FEST WRAP-UP BRING OUT THE LIONS! Craccum contributors review Mark Fullerton predicts the some literary luminaries outcomes of the forthcoming Lions Series [3] 360° Auckland Abroad Add the world to your degree Auckland Abroad Exchange Programme Application Deadline: July 1, 2017 for exchange in Semester 1, 2018 The 360° Auckland Abroad student exchange programme creates an opportunity for you to complete part of your University of Auckland degree overseas. You may be able to study for a semester or a year at one of our 130 partner universities in 25 countries. Scholarships and financial assistance are available. Come along to an Auckland Abroad information seminar held every Thursday at 2pm in iSPACE (level 4, Student Commons). There are 360° of exciting possibilities. Where will you go? www.auckland.ac.nz/360 [email protected] EDITORIAL Catriona Britton Samantha Gianotti The F-Word Margaret Atwood’s 1985 dystopian novel The in a later interview that the show is “obvious- ain’t about race, man. -

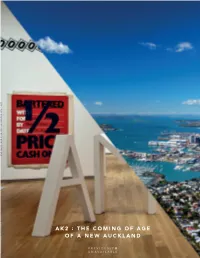

Ak2 : the Coming of Age of a New Auckland

AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE A NEW AUCKLAND PREVIOUSLY UNAVAILABLE PREVIOUSLY AK2 : THE COMING OF AGE OF A NEW AUCKLAND AK2: The Coming of Age of a New Auckland Published June 2014 by: Previously Unavailable www.previously.co [email protected] © 2014 Previously Unavailable Researched, written, curated & edited by: James Hurman, Principal, Previously Unavailable Acknowledgements: My huge thanks to all 52 of the people who generously gave their time to be part of this study. To Paul Dykzeul of Bauer Media who gave me access to Bauer’s panel of readers to complete the survey on Auckland pride and to Tanya Walshe, also of Bauer Media, who organised and debriefed the survey. To Jane Sweeney of Anthem who connected me with many of the people in this study and extremely kindly provided me with the desk upon which this document has been created. To the people at ATEED, Cooper & Company and Cheshire Architects who provided the photos. And to Dick Frizzell who donated his time and artistic eforts to draw his brilliant caricature of a New Aucklander. You’re all awesome. Thank you. Photo Credits: p.14 – Basketballers at Wynyard – Derrick Coetzee p.14 – Britomart signpost – Russell Street p.19 - Auckland from above - Robert Linsdell p.20 – Lantern Festival food stall – Russell Street p.20 – Art Exhibition – Big Blue Ocean p.40 – Auckland Museum – Adam Selwood p.40 – Diner Sign – Abaconda Management Group p.52 – Lorde – Constanza CH SOMETHING’S UP IN AUCKLAND “We had this chance that came up in Hawkes Bay – this land, two acres, right on the beach.