Glenn Gould, Oscar Peterson, and New World Virtuosities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

David Dubal Tem Dado Recitais De Piano E Masterclasses Em Todo O

David Dubal tem dado recitais de piano e masterclasses em todo o mundo, e foi jurado de competições internacionais de piano (incluindo o Van Cliburn International Piano Competition). Ele gravou vários CDs em conjunto com o pianista Stanley Waldoff para a gravadora Musical Heritage Society, e três discos foram remasterizados e lançados em CD pela gravadora Arkiv. Em 2013, Dubal participou do filme Holandês Nostalgia: a Música de Wim Statius Müller, comentando sobre as músicas do compositor, o qual foi seu professor em Ohio. Dubal lecionou na Juilliard School de 1983 a 2018, e na Manhattan School of Music de 1994 a 2015. Dubal escreveu vários livros, incluindo a Arte do Piano, Noites com Horowitz, Conversas com Menuhin, Reflexões do Teclado, Conversas com João Carlos Martins, Lembrando Horowitz e O Essencial Cânone da Música Clássica (um guia enciclopédico dos compositores proeminentes). Ele também escreveu e apresentou o documentário A Era Dourada do Piano, premiado com um Emmy e produzido por Peter Rosen. Dubal dá palestras semanais, Noites com Piano, na Good Shepherd-Faith Presbyterian Church, em Nova Iorque. Ele deu inúmeras palestras no Metropolitan Museum of Art sobre os grandes pianistas, mudanças sociais, história da música e tradição do piano. Suas palestras estão disponíveis em seu site: https://www.pianoevenings.com/david-dubal. Dubal é o anfitrião das palestras Sobre o Piano, um programa de performances comparativas de piano na WWFM e o anfitrião de Reflexões do Teclado, uma exploração semanal de gravações de piano, produzido na WQXR-FM. No final da década de 1990, ele apresentou uma série de programas de rádio intitulado The American Century, com foco em obras musicais de compositores Americanos do século XX, agora disponíveis no YouTube. -

Shall We Stomp?

Volume 36 • Issue 2 February 2008 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Shall We Stomp? The NJJS proudly presents the 39th Annual Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp ew Jersey’s longest Nrunning traditional jazz party roars into town once again on Sunday, March 2 when the 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp is pre- sented in the Grand Ballroom of the Birchwood Manor in Whippany, NJ — and you are cordially invited. Slated to take the ballroom stage for five hours of nearly non-stop jazz are the Smith Street Society Jazz Band, trumpeter Jon Erik-Kellso and his band, vocalist Barbara Rosene and group and George Gee’s Jump, Jivin’ Wailers PEABODY AT PEE WEE: Midori Asakura and Chad Fasca hot footing on the dance floor at the 2007 Stomp. Photo by Cheri Rogowsky. Story continued on page 26. 2008 Pee Wee Russell Memorial Stomp MARCH 2, 2008 Birchwood Manor, Whippany TICKETS NOW AVAILABLE see ad page 3, pages 8, 26, 27 ARTICLES Lorraine Foster/New at IJS . 34 Morris, Ocean . 48 William Paterson University . 19 in this issue: Classic Stine. 9 Zan Stewart’s Top 10. 35 Institute of Jazz Studies/ Lana’s Fine Dining . 21 NEW JERSEY JAZZ SOCIETY Jazz from Archives. 49 Jazzdagen Tours. 23 Big Band in the Sky . 10 Yours for a Song . 36 Pres Sez/NJJS Calendar Somewhere There’s Music . 50 Community Theatre. 25 & Bulletin Board. 2 Jazz U: College Jazz Scene . 18 REVIEWS The Name Dropper . 51 Watchung Arts Center. 31 Jazzfest at Sea. -

The Pianist's Freedom and the Work's Constrictions

The Pianist’s Freedom and the Work’s Constrictions What Tempo Fluctuation in Bach and Chopin Indicate Alisa Yuko Bernhard A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music (Performance) Sydney Conservatorium of Music University of Sydney 2017 Declaration I declare that the research presented here is my own original work and has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of a degree. Alisa Yuko Bernhard 10 November 2016 i Abstract The concept of the musical work has triggered much discussion: it has been defined and redefined, and at times attacked and deconstructed, by writers including Wolterstorff, Goodman, Levinson, Davies, Nattiez, Goehr, Abbate and Parmer, to name but a few. More often than not, it is treated either as an abstract sound-structure or, in contrast, as a culturally constructed concept, even a chimera. But what is a musical work to the performer, actively engaged in a “relationship” with the work he or she is interpreting? This question, not asked often enough in scholarship, can be used to yield fascinating insights into the ontological status of the work. My thesis therefore explores the relationship between the musical work and the performance, with a specific focus on classical pianists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I make use of two methodological starting-points for considering the nature of the work. Firstly, I survey what pianists have said and written in interviews and biographies regarding their role as interpreters of works. Secondly, I analyse pianists’ use of tempo fluctuation at structurally significant moments in a selection of pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach and Frederic Chopin. -

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Upside Down: Arctic Realities

Upside Down: Arctic Realities http://www.caareviews.org/reviews/1746 critical reviews of books, exhibitions, and projects in all areas and periods of art history and visual studies published by the College Art Association Donate to caa.reviews January 4, 2012 Edmund Carpenter, ed. Upside Down: Arctic Realities Exh. cat. Houston: Menil Collection, 2011. 232 pp.; 132 color ills.; 62 b/w ills. Cloth $50.00 (9780300169386) Exhibition schedule: Musée du quai Branly, Paris, September 30, 2008–January 11, 2009; Menil Collection, Houston, April 15—July 17, 2011 Marcia Brennan CrossRef DOI: 10.3202/caa.reviews.2012.2 Yup’ik, Southwest Alaska. “Tomanik” (wind-maker) mask or Summer/Winter mask (late 19th century). Wood, feathers, pigment, fiber. 37 x 16 x 10 in. (94 x 40.6 x 25.4 cm). © Rock Foundation, New York. Photo: Fred Gageneau. When describing the carved artworks of the Aboriginal people of the Arctic regions, the anthropologist Edmund Snow Carpenter once observed: “A distinctive mark of the traditional art is that many of the ivory carvings, generally of sea mammals, won’t stand up, but roll clumsily about. Each lacks a single, favored point of view, hence, a base. Indeed, they aren’t intended to be set in place and viewed, but rather to be worn or handled, turned this way and that. The carver himself explains his effort as a token of thanks for food or services received from the animal’s spirit” (16). Much like the individual artworks displayed in Upside Down: Arctic Realities, the exhibition itself could be seen as a composite phenomenon that is best approached from multiple perspectives at once and “turned this way and that.” In its creative conflations and inversions of Paleolithic and modern motifs, the show simultaneously cultivated the perspectives of ethnographic anthropology and contemporary art criticism, with their attendant conceptions of distanced criticality and aesthetic proximity. -

Robert GADEN: Slim GAILLARD

This discography is automatically generated by The JazzOmat Database System written by Thomas Wagner For private use only! ------------------------------------------ Robert GADEN: Robert Gaden -v,ldr; H.O. McFarlane, Karl Emmerling, Karl Nierenz -tp; Eduard Krause, Paul Hartmann -tb; Kurt Arlt, Joe Alex, Wolf Gradies -ts,as,bs; Hans Becker, Alex Beregowsky, Adalbert Luczkowski -v; Horst Kudritzki -p; Harold M. Kirchstein -g; Karl Grassnick -tu,b; Waldi Luczkowski - d; recorded September 1933 in Berlin 65485 ORIENT EXPRESS 2.47 EOD1717-2 Elec EG2859 Robert Gaden und sein Orchester; recorded September 16, 1933 in Berlin 108044 ORIENTEXPRESS 2.45 OD1717-2 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded December 1936 in Berlin 105298 MEIN ENTZÜCKENDES FRÄULEIN 2.21 ORA 1653-1 HMV EG3821 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded October 1938 in Berlin 106900 ICH HAB DAS GLÜCK GESEHEN 2.12 ORA3296-2 Elec EG6519 Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; recorded November 1938 in Berlin 106902 SIGNORINA 2.40 ORA3571-2 Elec EG6567 106962 SPANISCHER ZIGEUNERTANZ 2.45 ORA 3370-1 --- Robert Gaden mit seinem Orchester; Refraingesang: Rudi Schuricke; recorded September 1939 in Berlin 106907 TAUSEND SCHÖNE MÄRCHEN 2.56 ORA4169-1 Elec EG7098 ------------------------------------------ Slim GAILLARD: "Swing Street" Slim Gaillard -g,vib,vo; Slam Stewart -b; Sam Allen -p; Pompey 'Guts' Dobson -d; recorded February 17, 1938 in New York 9079 FLAT FOOT FLOOGIE 2.51 22318-4 Voc 4021 Some sources say that Lionel Hampton plays vibraphone. 98874 CHINATOWN MY CHINATOWN -

Focus 2020 Pioneering Women Composers of the 20Th Century

Focus 2020 Trailblazers Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century The Juilliard School presents 36th Annual Focus Festival Focus 2020 Trailblazers: Pioneering Women Composers of the 20th Century Joel Sachs, Director Odaline de la Martinez and Joel Sachs, Co-curators TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction to Focus 2020 3 For the Benefit of Women Composers 4 The 19th-Century Precursors 6 Acknowledgments 7 Program I Friday, January 24, 7:30pm 18 Program II Monday, January 27, 7:30pm 25 Program III Tuesday, January 28 Preconcert Roundtable, 6:30pm; Concert, 7:30pm 34 Program IV Wednesday, January 29, 7:30pm 44 Program V Thursday, January 30, 7:30pm 56 Program VI Friday, January 31, 7:30pm 67 Focus 2020 Staff These performances are supported in part by the Muriel Gluck Production Fund. Please make certain that all electronic devices are turned off during the performance. The taking of photographs and use of recording equipment are not permitted in the auditorium. Introduction to Focus 2020 by Joel Sachs The seed for this year’s Focus Festival was planted in December 2018 at a Juilliard doctoral recital by the Chilean violist Sergio Muñoz Leiva. I was especially struck by the sonata of Rebecca Clarke, an Anglo-American composer of the early 20th century who has been known largely by that one piece, now a staple of the viola repertory. Thinking about the challenges she faced in establishing her credibility as a professional composer, my mind went to a group of women in that period, roughly 1885 to 1930, who struggled to be accepted as professional composers rather than as professional performers writing as a secondary activity or as amateur composers. -

Symphony Nova Scotia Fonds (MS-5-14)

Dalhousie University Archives Finding Aid - Symphony Nova Scotia fonds (MS-5-14) Generated by the Archives Catalogue and Online Collections on January 24, 2017 Dalhousie University Archives 6225 University Avenue, 5th Floor, Killam Memorial Library Halifax Nova Scotia Canada B3H 4R2 Telephone: 902-494-3615 Email: [email protected] http://dal.ca/archives http://findingaids.library.dal.ca/symphony-nova-scotia-fonds Symphony Nova Scotia fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 4 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 6 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Administration and finance records of Symphony Nova Scotia (1984-2003) ............................................. 7 Budgets records of Symphony -

The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's Annual Report For

ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 Valuable Canadian Innovative Complete Creative Invigorating Trusted Complete Distinctive Relevant News People Trust Arts Sports Innovative Efficient Canadian Complete Excellence People Creative Inv Sports Efficient Culture Complete Efficien Efficient Creative Relevant Canadian Arts Renewed Excellence Relevant Peopl Canadian Culture Complete Valuable Complete Trusted Arts Excellence Culture CBC/RADIO-CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2001-2002 2001-2002 at a Glance CONNECTING CANADIANS DISTINCTIVELY CANADIAN CBC/Radio-Canada reflects Canada to CBC/Radio-Canada informs, enlightens Canadians by bringing diverse regional and entertains Canadians with unique, and cultural perspectives into their daily high-impact programming BY, FOR and lives, in English and French, on Television, ABOUT Canadians. Radio and the Internet. • Almost 90 per cent of prime time This past year, • CBC English Television has been programming on our English and French transformed to enhance distinctiveness Television networks was Canadian. Our CBC/Radio-Canada continued and reinforce regional presence and CBC Newsworld and RDI schedules were reflection. Our audience successes over 95 per cent Canadian. to set the standard for show we have re-connected with • The monumental Canada: A People’s Canadians – almost two-thirds watched broadcasting excellence History / Le Canada : Une histoire CBC English Television each week, populaire enthralled 15 million Canadian delivering 9.4 per cent of prime time in Canada, while innovating viewers, nearly half Canada’s population. and 7.6 per cent share of all-day viewing. and taking risks to deliver • The Last Chapter / Le Dernier chapitre • Through programming renewal, we have reached close to 5 million viewers for its even greater value to reinforced CBC French Television’s role first episode. -

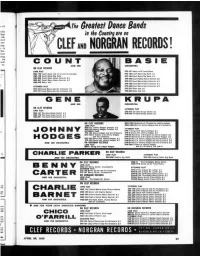

CLEF and NORGRAN RECORDS ’ Blic

ne Breitest Bence Bends ndly that In the Country ere on I ob- nted rec- ncy, 8 to CLEF AND NORGRAN RECORDS ’ blic. ■tion song Host ORCHESTRA ON CLEF RECORDS LONG PUT EPC-157 Dance with Count Basie MGC-120 Count Basle and his Orchestra Collates EPC IOS Count Basie Big Band sr 1 MGC-140 Count Basle Big Band EPC IM Count Basie Big Band sr 2 MGC «26 Count Basle Dance Session #1 EPC-220 Count Basle Dance Session # 1 MGC-G47 Count Basle Dance Session 02 EPC-221 Count Basie Dance Session #2 MGC-833 Basle la» EPC-338 Count Basie Dance Session #3 EXTENDED PUT EPC-338 Count Basle Dance Session #4 EPC-132 Count Basle and His Orchestra #1 EPC-251 Basie Jan #1 EPC-14? Count Basle and His Orchestra #2 EPC 252 Basie Jan #2 ORCHISfRA ON CLEF RECORDS EXTENBEB PUT LONG PUT EPC-247 The Gene Krupa Sextet # 1 MGC-147 The Gene Krupa Sextet #1 EPC-248 The Gene Krupa Sextet #2 MGC-152 The Gene Krupe Sextet #2 MGC 831 The Gene Krupa Sextet #3 ON CLEF RECOROS MGN-1004 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges LONS PUT MGN-10M More of Johnny Hodges end Hli Jrchestra MCC-111 Johnny Hodges Collates #1 MGC-12» Johnny Hodges Collates 02 EXTENOEB PUT EXTENDED PUT (PN-1 Swing with Johnny Hodges #1 EPC-12» Johnny Hodges «nd His Orchestra EPN-2 Swing with Johnny Hodges 02 (PC-148 Al Hibbler with johnny Hodges 6PN 28 Memorles ot Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #1 and His Orchestra (PN 27 Memorles of Elllngton by Johnny Hodges #2 EPC 183 Dance with Johnny Hodges #1 EPN-83 More iH Johnny Hodges end His Orchestra O1 EPC 164 Oance with Johnny Hodges #2 (PN-44 Mora of Johnny Hodges -

Trevor Tolley Jazz Recording Collection

TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction to collection ii Note on organization of 78rpm records iii Listing of recordings Tolley Collection 10 inch 78 rpm records 1 Tolley Collection 10 inch 33 rpm records 43 Tolley Collection 12 inch 78 rpm records 50 Tolley Collection 12 inch 33rpm LP records 54 Tolley Collection 7 inch 45 and 33rpm records 107 Tolley Collection 16 inch Radio Transcriptions 118 Tolley Collection Jazz CDs 119 Tolley Collection Test Pressings 139 Tolley Collection Non-Jazz LPs 142 TREVOR TOLLEY JAZZ RECORDING COLLECTION Trevor Tolley was a former Carleton professor of English and Dean of the Faculty of Arts from 1969 to 1974. He was also a serious jazz enthusiast and collector. Tolley has graciously bequeathed his entire collection of jazz records to Carleton University for faculty and students to appreciate and enjoy. The recordings represent 75 years of collecting, spanning the earliest jazz recordings to albums released in the 1970s. Born in Birmingham, England in 1927, his love for jazz began at the age of fourteen and from the age of seventeen he was publishing in many leading periodicals on the subject, such as Discography, Pickup, Jazz Monthly, The IAJRC Journal and Canada’s popular jazz magazine Coda. As well as having written various books on British poetry, he has also written two books on jazz: Discographical Essays (2009) and Codas: To a Life with Jazz (2013). Tolley was also president of the Montreal Vintage Music Society which also included Jacques Emond, whose vinyl collection is also housed in the Audio-Visual Resource Centre.