Introduction: Secret Sharer Why Do I Write?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies –

The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan Published by Self Improvement Online, Inc. http://www.SelfGrowth.com 20 Arie Drive, Marlboro, NJ 07746 ©Copyright by David Riklan Manufactured in the United States No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Limit of Liability / Disclaimer of Warranty: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. The author shall not be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages. The Top 101 Inspirational Movies – http://www.SelfGrowth.com The Top 101 Inspirational Movies Ever Made – by David Riklan TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 6 Spiritual Cinema 8 About SelfGrowth.com 10 Newer Inspirational Movies 11 Ranking Movie Title # 1 It’s a Wonderful Life 13 # 2 Forrest Gump 16 # 3 Field of Dreams 19 # 4 Rudy 22 # 5 Rocky 24 # 6 Chariots of -

Graham Greene Exhibition Catalogue

The Cherry Record Collection of Josephine Reid’s Papers and Books Relating to Our thanks to the following donors who made the acquisition possible: Paul Almond (1949) GRAHAM GREENE Professor John Stephenson (1953) Professor John-Christopher Spender (1957) Roger Jefferies (1957) Paul Lewis (1958) Peter Buckman (1959) Matthew Nimetz (1960) Doug Rosenthal (1961) Alan James (1962) Stephen Crew (1964) Jim Rogers (1964) Emeritus Professor Paul Crittenden (1965) Alan Heeks (1966) Geoff Wright (1967) Neil Record (1972) Julie Record Richard Jones (1977) Mark Storey (1981) Danny Truell (1982) Alison Roberts (1984) Claire Foster-Gilbert (1984) Virginia Preston (1985) Richard Locke (1985) Jonathan Lewin (1992) Adam Dixon (1994) Sarah Longair (1998) Jo Valentine (2001) Jeff Kulkarni (2001) Sean McDaniel (2002) Alice McDaniel (2003) Blackwell Charitable Trust Friends of the National Libraries ISBN 978-1-78280-500-7 An exhibition held at BALLIOL COLLEGE HISTORIC COLLECTIONS CENTRE 9 781782 805007 > ST CROSS CHURCH, ST CROSS ROAD, OXFORD 25 & 26 April 2015 EXHIBITION AND CATALOGUE BY Naomi Tiley Librarian, Balliol College Anna Sander Archivist, Balliol College FOREWORD BY Sir Anthony Kenny Master of Balliol College 1978–1989 Seamus Perry COVER ILLUSTRATIONS: Fellow Librarian, Balliol College Studio portrait of Josephine Reid taken in the late 1940s or early Neil Record 1950s. Photographer unknown. Balliol 1972 Handwriting © Josephine Reid’s Estate Details from postcards from Graham Greene to Josephine Reid © Verdant SA. The organisers are indebted to -

The Magnificent Ambersons Review

The magnificent ambersons review Continue For the 2002 television version, watch The Magnificent Amberers (the 2002 film). 1942 film by Orson Helles, Robert Wise Magnificent AmbersonsTheatrical release poster with illustrations by Norman Rockwell 1Director Orson WellesProduced Orson WellesScreenplay Orson WellesBased on Magnificent Amberersby Booth TarkingtonStarring Joseph Cotten Dostren Dolores Costello Ann Baxter Tim Holt Agnes Moorhead Ray Collins Erskine Sanford Richard Bennett Comments Orson WellesMusic No Credit to FilmCinematographyStanley CortezEd ByRobert WiseProductioncompany RKO Radio PicturesMercury Productions Distributed RKO Radio PicturesRelease Date July 10 , 1942 (1942-07-10) Running time 88 minutes148 minutes (original)131 minutes (preview)Country Of the United StatesLanguageEnglishBudget $1.1 million:71-72Box office $1 million (US rent) The Magnificent Ambers (U.S. - American drama 1942, written, produced and directed by Orson Velez. Welles will adapt Booth Tarkington's Pulitzer Prize-winning 1918 novel, about the leaning fortunes of the wealthy Midwestern family and the social changes brought by the car era. The film stars Joseph Cotten, Dolores Costello, Ann Baxter, Tim Holt, Agnes Moorhead and Ray Collins, while Welles has a narration. Heles lost control of RKO's The Magnificent Amberers edit, and the final version released to viewers was significantly different from his rough cut of the film. More than an hour of footage was cut in the studio, which also shot and replaced a happier ending. While Veles's extensive notes on how he wanted the film to be shortened survived, the cut frames were destroyed. Composer Bernard Herrmann insisted that his merit be removed when, like the film itself, his score was heavily edited by the studio. -

The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1

Contents Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances Screen Valentines: Great Movie Romances .......... 2 February 7–March 20 Vivien Leigh 100th ......................................... 4 30th Anniversary! 60th Anniversary! Burt Lancaster, Part 1 ...................................... 5 In time for Valentine's Day, and continuing into March, 70mm Print! JOURNEY TO ITALY [Viaggio In Italia] Play Ball! Hollywood and the AFI Silver offers a selection of great movie romances from STARMAN Fri, Feb 21, 7:15; Sat, Feb 22, 1:00; Wed, Feb 26, 9:15 across the decades, from 1930s screwball comedy to Fri, Mar 7, 9:45; Wed, Mar 12, 9:15 British couple Ingrid Bergman and George Sanders see their American Pastime ........................................... 8 the quirky rom-coms of today. This year’s lineup is bigger Jeff Bridges earned a Best Actor Oscar nomination for his portrayal of an Courtesy of RKO Pictures strained marriage come undone on a trip to Naples to dispose Action! The Films of Raoul Walsh, Part 1 .......... 10 than ever, including a trio of screwball comedies from alien from outer space who adopts the human form of Karen Allen’s recently of Sanders’ deceased uncle’s estate. But after threatening each Courtesy of Hollywood Pictures the magical movie year of 1939, celebrating their 75th Raoul Peck Retrospective ............................... 12 deceased husband in this beguiling, romantic sci-fi from genre innovator John other with divorce and separating for most of the trip, the two anniversaries this year. Carpenter. His starship shot down by U.S. air defenses over Wisconsin, are surprised to find their union rekindled and their spirits moved Festival of New Spanish Cinema .................... -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Lovers and Friends; Or Modern Attachments

Author: Anne Julia Kemble Hatton Title: Lovers and Friends; or, Modern Attachments Place of publication: London Publisher: Printed at the Minerva Press for A. K. Newman and Co. Date of publication: 1821 Edition: 1st ed. Number of volumes: 5 LOVERS AND FRIENDS. A NOVEL. Printed by J. Darling, Leadenhall-street London. LOVERS AND FRIENDS; OR, MODERN ATTACHMENTS. A NOVEL. IN FIVE VOLUMES. BY ANNE OF SWANSEA, AUTHOR OF CONVICTION, GONZALO DE BALDIVIA, CHRONICLES OF AN ILLUSTRIOUS HOUSE, SECRET AVENGERS, SECRETS IN EVERY MANSION, CAMBRIAN PICTURES, CESARIO ROSALBA, &c.&c. “I hold a mirror up for men to see How bad they are, how good they ought to be.” VOL. 1. LONDON: Printed at the Minerva Press for A.K. NEWMAN AND CO. LEADENHALLSTREET. 1821. INSCRIPTION. WITH SINCERE ADMIRATION OF HIS MUSICAL GENIUS, AND THE MOST PERFECT RESPECT FOR HIS HONOURABLE CHARACTER, THESE VOLUMES ARE INSCRIBED TO JOHN EMDIN, ESQ. BY HIS OBLIGED FRIEND AND DEVOTED SERVANT, ANN OF SWANSEA. College-street, Swansea, July 10, 1820. PREFACE. KING Solomon, the very wisest of all wise sages, past, present, and to come, declared, in his day, there was nothing new under the sun: how then can the weak brain of a modern author (ye sons and daughters of fire-eyed Genius, be not, I beseech you, offended; I only mean weak, when compared with the brain of king Solomon) pretend to lead the fastidious critic through paths untrodden before, or present to his lynx-like sight sentiments and incidents unheard of either in prose or verse? The difficulty of twisting, twining, and winding together, three or four volumes, of sufficient interest to attract public attention, is labour that requires an ingenuity few have genius enough to accomplish, and affords a weighty reason why prefaces are growing out of fashion; for an author finds his inventive faculties spun as thin as a cobweb in supplying the requisite number of pages for his story, without wasting his metaphors, sublimity, and brilliance, on a preface. -

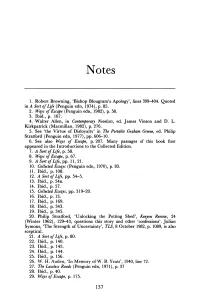

'Bishop Blougram's Apology', Lines 39~04. Quoted in a Sort of Life (Penguin Edn, 1974), P

Notes 1. Robert Browning, 'Bishop Blougram's Apology', lines 39~04. Quoted in A Sort of Life (Penguin edn, 1974), p. 85. 2. Wqys of Escape (Penguin edn, 1982), p. 58. 3. Ibid., p. 167. 4. Walter Allen, in Contemporary Novelists, ed. James Vinson and D. L. Kirkpatrick (Macmillan, 1982), p. 276. 5. See 'the Virtue of Disloyalty' in The Portable Graham Greene, ed. Philip Stratford (Penguin edn, 1977), pp. 606-10. 6. See also Ways of Escape, p. 207. Many passages of this book first appeared in the Introductions to the Collected Edition. 7. A Sort of Life, p. 58. 8. Ways of Escape, p. 67. 9. A Sort of Life, pp. 11, 21. 10. Collected Essays (Penguin edn, 1970), p. 83. 11. Ibid., p. 108. 12. A Sort of Life, pp. 54-5. 13. Ibid., p. 54n. 14. Ibid., p. 57. 15. Collected Essays, pp. 319-20. 16. Ibid., p. 13. 17. Ibid., p. 169. 18. Ibid., p. 343. 19. Ibid., p. 345. 20. Philip Stratford, 'Unlocking the Potting Shed', KeT!Jon Review, 24 (Winter 1962), 129-43, questions this story and other 'confessions'. Julian Symons, 'The Strength of Uncertainty', TLS, 8 October 1982, p. 1089, is also sceptical. 21. A Sort of Life, p. 80. 22. Ibid., p. 140. 23. Ibid., p. 145. 24. Ibid., p. 144. 25. Ibid., p. 156. 26. W. H. Auden, 'In Memory ofW. B. Yeats', 1940, line 72. 27. The Lawless Roads (Penguin edn, 1971), p. 37 28. Ibid., p. 40. 29. Ways of Escape, p. 175. 137 138 Notes 30. Ibid., p. -

Teodor Mateoc Editor

TEODOR MATEOC editor ------------------------------------------------ Cultural Texts and Contexts in the English Speaking World (V) Teodor Mateoc editor CULTURAL TEXTS AND CONTEXTS IN THE ENGLISH SPEAKING WORLD (V) Editura Universităţii din Oradea 2017 Editor: TEODOR MATEOC Editorial Board: IOANA CISTELECAN MADALINA PANTEA GIULIA SUCIU EVA SZEKELY Advisory Board JOSE ANTONIO ALVAREZ AMOROS University of Alicante, Spaian ANDREI AVRAM University of Bucharest, Romania ROGER CRAIK University of Ohio, USA SILVIE CRINQUAND University of Bourgogne, France SEAN DARMODY Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland ANDRZEJ DOROBEK Instytut Neofilologii, Plock, Poland STANISLAV KOLAR University of Ostrava, Czech Republic ELISABETTA MARINO University Tor Vergata, Rome MIRCEA MIHAES Universitatea de Vest, Timisoara VIRGIL STANCIU Babes Bolyai University, Cluj-Napoca PAUL WILSON University of Lodz, Poland DANIELA FRANCESCA VIRDIS University of Cagliari, Italy INGRIDA ZINDZIUVIENE Vytautas Magnus University, Kaunas, Lithuania Publisher The Department of English Language and Literature Faculty of Letters University of Oradea ISSN 2067-5348 CONTENTS Introduction Cultural Texts and Contexts in the English Speaking World: The Fifth Edition ............................................................................. 9 I. BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH LITERATURE Adela Dumitrescu, Physiognomy of Fashion in Fiction: Jane Austen ..... 17 Elisabetta Marino, “Unmaidenly” Maidens: Rhoda Broughton’s Controversial Heroines ................................................ 23 Alexandru -

Norman Macleod

Norman Macleod "This strange, rather sad story": The Reflexive Design of Graham Greene's The Third Man. The circumstances surrounding the genesis and composition of Gra ham Greene's The Third Man ( 1950) have recently been recalled by Judy Adamson and Philip Stratford, in an essay1 largely devoted to characterizing some quite unwarranted editorial emendations which differentiate the earliest American editions from British (and other textually sound) versions of The Third Man. It turns out that these are changes which had the effect of giving the American reader a text which (for whatever reasons, possibly political) presented the Ameri can and Russian occupation forces in Vienna, and the central charac ter of Harry Lime, and his dishonourable deeds and connections, in a blander, softer light than Greene could ever have intended; indeed, according to Adamson and Stratford, Greene did not "know of the extensive changes made to his story in the American book and now claims to be 'horrified' by them"2 • Such obscurely purposeful editorial meddlings are perhaps the kind of thing that the textual and creative history of The Third Man could have led us to expect: they can be placed alongside other more official changes (usually introduced with Greene's approval and frequently of his own doing) which befell the original tale in its transposition from idea-resuscitated-from-old notebook to story to treatment to script to finished film. Adamson and Stratford show that these approved and 'official' changes involved revisions both of dramatis personae and of plot, and that they were often introduced for good artistic or practical reasons. -

BFI Press Release: Missing Believed Wiped Bumper Christmas Stocking

For Immediate Release: Tuesday 7 November 2017, London. The BFI’s Missing Believed Wiped returns to BFI Southbank this December to present British television rediscoveries, not seen by audiences for decades, since their original transmission dates. The exciting, bespoke line-up of TV gems feature some of our most-loved television celebrities and iconic characters including Alf Garnett in Till Death Us Do Part: Sex Before Marriage, Cilla Black in her eponymous BBC show featuring Dudley Moore , Jimmy Edwards in Whack-O!, a rare interview with Peter Davison about playing Doctor Who and a significant screen debut from a young Pete Postlethwaite. Lost for 50 years and thought only to survive in part, Till Death Us Do: Sex Before Marriage, originally broadcast on 2 January, 1967 on BBC1, sees Warren Mitchell’s Alf Garnett rail against the permissive society, featuring guest star John Junkin alongside regular cast members Dandy Nichols, Anthony Booth and Una Stubbs. Although the existence of this missing episode from the 2nd series has been known for some years, previous attempts to screen the episode had been refused with the print in the hands of a private collector. Having recently changed hands, MBW is delighted that access has been granted for this special one off screening, for one of 1960s best known and controversial UK television characters. Following last year’s successful screening of a previously lost episode of Jimmy Edwards’s popular 1950s BBC school-themed comedy romp Whack-O!, this year’s MBW programme includes a 1959 episode entitled The Empty Cash Box. Written by Frank Muir and Dennis Norden and starring Jimmy Edwards as the cane-happy headmaster, this episode was originally broadcast on the BBC on 1st December 1959. -

Cervantes and the Spanish Baroque Aesthetics in the Novels of Graham Greene

TESIS DOCTORAL Título Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene Autor/es Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Director/es Carlos Villar Flor Facultad Facultad de Letras y de la Educación Titulación Departamento Filologías Modernas Curso Académico Cervantes and the spanish baroque aesthetics in the novels of Graham Greene, tesis doctoral de Ismael Ibáñez Rosales, dirigida por Carlos Villar Flor (publicada por la Universidad de La Rioja), se difunde bajo una Licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial-SinObraDerivada 3.0 Unported. Permisos que vayan más allá de lo cubierto por esta licencia pueden solicitarse a los titulares del copyright. © El autor © Universidad de La Rioja, Servicio de Publicaciones, 2016 publicaciones.unirioja.es E-mail: [email protected] CERVANTES AND THE SPANISH BAROQUE AESTHETICS IN THE NOVELS OF GRAHAM GREENE By Ismael Ibáñez Rosales Supervised by Carlos Villar Flor Ph.D A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At University of La Rioja, Spain. 2015 Ibáñez-Rosales 2 Ibáñez-Rosales CONTENTS Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………………….......5 INTRODUCTION ...…………………………………………………………...….7 METHODOLOGY AND STRUCTURE………………………………….……..12 STATE OF THE ART ..……….………………………………………………...31 PART I: SPAIN, CATHOLICISM AND THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN (CATHOLIC) NOVEL………………………………………38 I.1 A CATHOLIC NOVEL?......................................................................39 I.2 ENGLISH CATHOLICISM………………………………………….58 I.3 THE ORIGIN OF THE MODERN -

Track 1 Juke Box Jury

CD1: 1959-1965 CD4: 1971-1977 Track 1 Juke Box Jury Tracks 1-6 Mary, Queen Of Scots Track 2 Beat Girl Track 7 The Persuaders Track 3 Never Let Go Track 8 They Might Be Giants Track 4 Beat for Beatniks Track 9 Alice’s Adventures In Wonderland Track 5 The Girl With The Sun In Her Hair Tracks 10-11 The Man With The Golden Gun Track 6 Dr. No Track 12 The Dove Track 7 From Russia With Love Track 13 The Tamarind Seed Tracks 8-9 Goldfinger Track 14 Love Among The Ruins Tracks 10-17 Zulu Tracks 15-19 Robin And Marian Track 18 Séance On A Wet Afternoon Track 20 King Kong Tracks 19-20 Thunderball Track 21 Eleanor And Franklin Track 21 The Ipcress File Track 22 The Deep Track 22 The Knack... And How To Get It CD5: 1978-1983 CD2: 1965-1969 Track 1 The Betsy Track 1 King Rat Tracks 2-3 Moonraker Track 2 Mister Moses Track 4 The Black Hole Track 3 Born Free Track 5 Hanover Street Track 4 The Wrong Box Track 6 The Corn Is Green Track 5 The Chase Tracks 7-12 Raise The Titanic Track 6 The Quiller Memorandum Track 13 Somewhere In Time Track 7-8 You Only Live Twice Track 14 Body Heat Tracks 9-14 The Lion In Winter Track 15 Frances Track 15 Deadfall Track 16 Hammett Tracks 16-17 On Her Majesty’s Secret Service Tracks 17-18 Octopussy CD3: 1969-1971 CD6: 1983-2001 Track 1 Midnight Cowboy Track 1 High Road To China Track 2 The Appointment Track 2 The Cotton Club Tracks 3-9 The Last Valley Track 3 Until September Track 10 Monte Walsh Track 4 A View To A Kill Tracks 11-12 Diamonds Are Forever Track 5 Out Of Africa Tracks 13-21 Walkabout Track 6 My Sister’s Keeper