Measuring the Effectiveness of Living Wage Policy Implementation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

December 2015

Fall 2015 OUR TIME HAS COME TOGETHER, WE CAN HELP ELECT CANADA’S FIRST NDP GOVERNMENT The newsletter of CUPE Alberta Victories for working people Since its election on May 5th, the Notley government has moved on two long standing issues of importance to working Albertans. In June, Jobs, Skills Training and Labour Minister, Lori Sigurdson announced that Alberta would no longer have the lowest minimum wage in Canada. The NDP raised minimum wage from $10.20 to $11.20, and increased the rate for alcohol servers to $10.70. The government also indicated it would fulfill its election promise to raise the minimum wage to $15/hour by 2018 and eliminate the separate wage rate for alcohol servers in 2016. Prior to the increase, which took affect October 1st, Alberta had the lowest minimum wage in Canada. The Notley government is the first jurisdiction in Canada to announce a $15 minimum wage, although several US Cities have already enacted it. Following the minimum wage increase the NDP government introduced legislation in November to include farmworkers in labour law. Prior to the legislation – Alberta was the only remaining province Farmworkers of Alberta, applauded the move, pointing where agricultural workers were not allowed to join out that since every other province had already made unions, were not covered by WCB, and were not these changes, it was long overdue. protected by Employment Standards or Health & Safety “We’re the only jurisdiction in North America and the regulations. In fact, worker deaths on farms could not European Union that has no standards at all. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road. -

2016 Medicine Hat & District Chamber of Commerce Policy Book

2018-2019 Policy Book Last Updated: February 2020 With the largest and most influential business organizations locally, provincially and federally, the Chamber network is the most unified, valued and influential business network in Canada and works together to shape policy and programs that will make a difference to businesses in our region. 1 POLICY BOOK 2018- 2019 APPROVED POLICIES FOR THE MEDICINE HAT & DISTRICT CHAMBER OF COMMERCE MUNICIPAL Municipal Election Policy ........................................................................................................................................................................ Page 6 Approved May 2012, Renewed December 2012, Amended May 2017 Defining a Process for Electorate Information ....................................................................................................................................... Page 7 Approved December 2012, Amended September 2013 Opposition to Land Transfer Tax ............................................................................................................................................................ Page 8 Approved March 2013 Municipal Red Tape Reduction ............................................................................................................................................................ Page 10 Approved March 2013 Tax Equity: Narrowing the Gap Between Residential and Non-Residential Property Taxes ............................................................. Page 13 Approved January 2018 Sustainable -

Federal Minimum Wage

Federal Minimum Wage Issue Paper This paper is one of a series of papers prepared by the Secretariat to the Expert Panel on Modern Federal Labour Standards as background information to stimulate the Panel's discussions. The papers do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government of Canada. January 2019 FEDERAL MINIMUM WAGE ISSUE PAPER ISSUE For more than 20 years, the federal minimum wage has been pegged in the Canada Labour Code to the minimum wage rate in the province or territory in which the employee is usually employed. Should this approach be maintained or should a freestanding federal minimum wage be reinstated? If a freestanding rate were to be adopted, how should it be set, at what level and who should be entitled to it? BACKGROUND The minimum wage is the lowest wage rate that an employer can legally pay its employees and is a core labour standard. The underlying policy intent for establishing minimum wages varies. Governments have historically put them in place with a view to protecting non-unionized workers, reducing the number of low-paying jobs, alleviating poverty, creating incentives to work, addressing inequality and stimulating growth through increased demand. Minimum wages are also set and adjusted in different ways: in legislation or regulations; by the government-of-the-day or an independent board; and based on inflation, average wage rates or other economic factors. The first minimum wage rates were established in Canada in the early 20th century and applied primarily to women and children. Manitoba and British Columbia introduced minimum wage legislation in 1918 and Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and Saskatchewan followed suit in 1920. -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 113 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 160 WASHINGTON, THURSDAY, JANUARY 9, 2014 No. 5 House of Representatives The House met at 10 a.m. and was the world, many of them trafficked for This January designated as National called to order by the Speaker pro tem- labor, but increasingly for underaged Slavery and Human Trafficking Pre- pore (Mr. MESSER). girls. For young women, this is a case vention Month is a perfect time to f where they are exploited in this traf- shine a spotlight on the dark issue of ficking as well. trafficking, but awareness is only a DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO Even in my work as chairman of the first step. More needs to be done. TEMPORE Foreign Affairs Committee, I have To that end, I would urge my col- The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- learned that human trafficking is no leagues to join me in cosponsoring H.R. fore the House the following commu- longer just a problem ‘‘over there.’’ It 3344, the Fraudulent Overseas Recruit- nication from the Speaker: is a problem in our communities here. ment and Trafficking Elimination Act, It is a problem in developing econo- to combat one critical form of recur- WASHINGTON, DC, ring abuse: namely, that is unscrupu- January 9, 2014. mies, but also it is a problem in the I hereby appoint the Honorable LUKE United States and in Europe. It is a lous recruiters. By targeting the re- MESSER to act as Speaker pro tempore on scourge even in the communities that cruiters we can do a lot—these recruit- this day. -

British Columbia British

BC Newcomers’ Guide to Resources and Services Resources Guide to BC Newcomers’ British Columbia Newcomers’ Guide to Resources and Services Vernon Edition 2014 Edition Please note 2014 Vernon Edition: The information in this guide is up to date at the time of printing. Names, addresses and telephone numbers may change, and publications go out of print, without notice. For more up-to-date information, please visit: www.welcomebc.ca This guide has been written using the Canadian Language Benchmark 4 (CLB 4) level to meet the needs of non-English speaking newcomers. To order copies of the Acknowledgements Provincial Newcomers’ Guide (2014 Edition) The Vernon edition of the BC Newcomers’ Guide • Shelley Motz and Timothy Tucker, Project Managers is available online at www.welcomebc.ca. Print • Barbara Carver, Baytree Communications, copies may be available through Vernon and District Project Coordinator and Editor Immigrant Services Society www.vdiss.com • Brigitt Johnson, 2014 Update Consultant Print copies of the provincial guide are available free • Reber Creative, Design Update and Layout of charge while quantities last. The provincial guide is also available online in the following languages: • Andrea Scott, Big Red Pen, Proofreading Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional), • Gillian Ruemke-Douglas and Nola Johnston, Farsi (Persian), French, Korean, Punjabi, Russian, Illustrations Spanish and Vietnamese. You can order copies of the provincial guide by filling in the resource order form at: www.welcomebc.ca/ newcomers_guide/newcomerguide.aspx. You can also Library and Archives Canada request copies by telephone or e-mail. Please include Cataloguing in Publication Data your contact name, address, postal code and phone Main entry under title: number with “B.C. -

Myths and Facts About the Minimum Wage in BC We Can Avoid the Need for Large One-Time Increases in the Future Simply by Indexing the Minimum Wage to Inflation

Myths and Facts About the Minimum Wage in BC WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE A MINIMUM WAGE earner in British Columbia? It means making $8 per hour — or as little as $6 if you’re getting the so-called “training wage.” If you work full-time, it means paydays that bring in at most $640 — and that’s before deductions. It means seeing your buying power eaten away year after year by rising living costs — BC’s minimum wage has been frozen since 2001, but you pay 2011 prices just like everyone else. And it means living on an annual income that is well below the poverty line for a single person. Back in 2001, BC had the highest minimum wage in Canada. However, other provinces have since made increases, leaving BC at the bottom of the rankings with the lowest minimum wages in the entire country. It is time to raise the minimum wage. And while we are at it, we should take politics out of the equation by developing a clear rationale for how it is set. We propose that a single person working full-time year-round should earn (at least) enough to live above the poverty line. The idea that someone working full-time, full-year should be able to get out of poverty is a clear, transparent policy decision that should determine the minimum wage in BC and in other provinces. Equally important is to legislate regularly scheduled increases tied to inflation, to ensure low-wage workers do not face what amounts to a pay cut as a result of rising prices. -

Bold Ideas for State Action

GETTY/GEORGE ROSE Bold Ideas for State Action By the Center for American Progress May 2018 WWW.AMERICANPROGRESS.ORG Bold Ideas for State Action By the Center for American Progress May 2018 Contents 1 Introduction and summary 4 Economy 17 Education 30 Early childhood 36 Health care 43 Restoring democracy 50 Clean energy and the environment 57 Women and families 64 Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer rights 67 Immigration 72 Criminal justice 79 Gun violence prevention 84 Conclusion 85 Endnotes Introduction and summary The past several decades have not been kind to America’s working families. Costs have skyrocketed while wages remain stagnant. Many of the jobs that have returned in the wake of the Great Recession have often offered lower wages and benefits, leaving Americans without college degrees particularly vulnerable. Fissures in the country are more apparent than ever, as access to opportunity is radically different between communities; the wealthiest grow richer while working families find themselves increasingly strapped. As a result of perpetual underinvestment in infrastructure, education, and other domestic priorities, the future for too many Americans looks increasingly grim, unequal, and uncertain. Federal policies passed or implemented in the past year will largely result in expanded inequality, not in rebuilding the middle class. The new tax law, as pushed by the Trump administration and congressional leadership, gives billions of dollars in tax cuts to companies and the wealthiest Americans instead of providing further support to those who need it most. As was true in the 2000s and more recently in states such as Kansas, showering tax giveaways on the wealthiest individuals and corporations does not create jobs or raise wages.1 Rather, when the baseless promises of economic growth do not materialize, the result is lower revenues and, ultimately, major cuts to critical investments in areas such as schools, infrastructure, and public services. -

We Are Ontario's Catholic Teachers

Position Papers TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Setting every young learner on the path to success Early childhood education and care is a vital public investment ......................................................................... 4 Full-day Kindergarten builds a solid foundation for every student ................................................................... 6 Building safe and inclusive school communities The well-being of students and teachers is paramount ................................................................................................ 8 Targeted classroom funding can help remove barriers to learning ................................................................... 11 Investment in Indigenous education will improve outcomes for all learners ........................................ 12 Additional resources are necessary to support students with special education needs .................................................................................................................................................................. 13 Going beyond the basics of learning Catholic education provides unique and important value .......................................................................................... 15 Class size matters .................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Geotour Guide for Terrace, BC

H COLU IS M IT B R IA B G E Y O E V LO R GICAL SU BC Geological Survey Geofile 2007-10 GeotourGeotour guide guide for for Terrace, Terrace, BC BC Bob Turner, Natural Resources Canada JoAnne Nelson, BC Geological Survey Richard Franklin, Saanich, BC Gordon Weary, Tony Walker, Bonnie Hayward,and Cathy McRae, Terrace, BC GeoTour Guide for Terrace, B.C. Our land. Our Community. Bob Turner, Natural Resources Canada, Vancouver, B.C; JoAnne Nelson, BC Geological Survey, Victoria, B.C.; Richard Franklin, North Saanich, B.C.; Gordon Weary, Northwest Community College; and Tony Walker, Bonnie Hayward, and Cathy McRae, Terrace, B.C. Figure 1. View from Birch Bench subdivision looking southwest across the eastern end of Terrace, the Skeena River, Ferry Island (left), and the Coast Mountains (back, right). The Terrace Airport is located on the flat bench on skyline to the left. We live within the great Coast Range where the Skeena River flowing west to the Pacific crosses the wide north-south Kitsumkalum-Kitimat Valley. This region is underlain by diverse geological materials and is continually shaped by earth processes. Terrace, like other communities, is dependent on the Earth for water, food, materials and energy. Not only does the Earth provide resources, but it accepts our wastes. This GeoTour fieldguide explores how our community of Terrace ’lives off the land‘. What earth materials underlie this landscape and how do they affect us? How has the local landscape shaped human use of our area? What local earth resources do we depend on? Where does our supply of drinking water come from? Where does our sewage go? Where does our garbage go? Where does the energy which fuels our lives come from? Are we sustaining the land that sustains us? This guide tours the geological landscape of Terrace and reveals its story. -

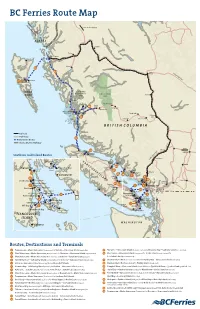

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver