The Misappropriation Theory of Insider Trading: Its Past, Present, and Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Capital Compounders How to Beat the Market and Make Money Investing in Growth Stocks Revised & Expanded Second Edition

Capital Compounders How to Beat the Market and Make Money Investing in Growth Stocks Revised & Expanded Second Edition Robin R. Speziale National Bestselling Author, Market Masters [email protected] | RobinSpeziale.com Copyright © 2018 Robin R. Speziale All Rights Reserved. ISBN: 978-1-7202-1080-1 DISCLAIMER Robin Speziale is not a register investment advisor, broker, or dealer. Readers are advised that the content herein should only be used solely for informational purposes. The information in “Capital Compounders” is not investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy or sell any securities. Robin Speziale does not propose to tell or suggest which investment securities readers should buy or sell. Readers are solely responsible for their own investment decisions. Investing involves risk, including loss of principal. Consult a registered professional. CONTENTS START HERE vi INTRODUCTION 1 1 How I Built a $300,000+ Stock Portfolio Before 9 30 (And How You Can Too!) My 8-Step Wealth Building Journey 2 Growth Investing vs. Value Investing 21 3 My 72 Rules for Investing in Stocks 28 4 Capital Compounders (Part 1/2) 77 5 Next Capital Compounders (Part 2/2) 88 6 Think Short: Becoming a Smarter Investor 96 7 Small Companies; Big Dreams 106 8 How to Find Tenbaggers 123 9 How I Manage My Stock Portfolio and Generate 131 Outsized Returns – The Three Bucket Model 10 How This Hedge Fund Manager Achieved a 141 24% Compound Annual Return (Since 1998!) 11 100+ Baggers – Top 30 Super Stocks 145 12 Small Cap Ideas – Tech Investor Interview -

Cornell Alumni News

VOL. XX., No. 11 [PRICE TEN CENTS] DECEMBER 6, 1917 Hundreds of Applicants for the Officers' Training Camps List of Faculty Members in the National Service An Undergraduate Demand for Higher Scholarship Standards Two More Cornell Men Receive the War Cross Pennsylvania 37, Cornell 0 ITHACA, NEW YORK CORNELL ALUMNI NEWS The Farmers' Loan and Herbert G. Ogden Jas. H. Oliphant & Co. E. E., '97 Trust Company ALFRED L. NORRIS, FLOYD W. MUNDY '98 Attorney and Counsellor at Law J. NORRIS OLIPHANT Όl 16, 18, 20, 22 William St., New York Patents and Patent Causes J. J, BRYANT, jr., '98, FRANK L. VAN WIE Branch, 475 Fifth Ave. 120 Broadway New York Members New York Stock Exchange T Λxrτϊr»xr ί 16 Pal1 Mal1 East» S W 1 and Chicago Stock Exchange LONDON \ 26 Old Broad Street, E. C. 2 PARIS 41 Boulevard Haussman Going to Ithaca? New York Office, 61 Broadway Chicago Office,711 The Rookery LETTERS OF CREDIT Use the "Short Line" FOREIGN EXCHANGES between CABLE TRANSFERS Auburn (Monroe St.) and Ithaca Cascadilla School The Leading Better Quicker Cheaper Direct connections at Auburn with Preparatory School for Cornell New York Central Trains for Syra- Located at the edge of the University Do You Use cuse, Albany and Boston. campus. Exceptional advantages for college entrance work. Congenial living. Press Clippings? Athletic training. Certificate privilege. For information and catalogue address: It will more than pay you to secure our extensive service cover- W. D. Funkhouser, Principal ing all subjects, trade and personal Ithaca, N. Y. and get the benefit of the best and Trustees most systematic reading of all papers and periodicals, here and Franklin C. -

100-Baggers Copyright © Agora Financial, LLC, 2015 All Rights Reserved

10BAGGER0S STOCKS THAT RETURN 100-TO-1 AND HOW TO FIND THEM 10BAGGER0S STOCKS THAT RETURN 100-TO-1 AND HOW TO FIND THEM CHRISTOPHER MAYER Laissez Faire Books In memory of Thomas W. Phelps, author of the first book on 100-baggers Copyright © Agora Financial, LLC, 2015 All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-1-6212916-5-7 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Published by Laissez Faire Books, 808 St. Paul Street, Baltimore, Maryland www.lfb.org Cover and Layout Design: Andre Cawley CONTENTS Chapter 1: Introducing 100-Baggers .............................................................................1 Chapter 2: Anybody Can Do This: True Stories....................................................... 11 Chapter 3: The Coffee-Can Portfolio ..........................................................................15 Chapter 4: 4 Studies of 100-Baggers ........................................................................31 Chapter 5: The 100-Baggers of the Last 50 Years ...............................................43 Chapter 6: The Key to 100-Baggers .......................................................................... 75 Chapter 7: Owner-Operators: Skin in the Game ...................................................83 Chapter 8: The Outsiders: The Best CEOs ..............................................................93 Chapter 9: Secrets of an 18,000-Bagger ............................................................... 103 Chapter 10: Kelly’s Heroes: Bet Big .............................................................................111 Chapter -

Le Nord 04/05/05 Part.1

L'hebdo francophone #1 de la région depuis 1976 ! À L’INTÉRIEUR Budget municipal....HA3 Campagne «Visons la propreté»...........HA5 Tournoi des Deux Glaces.............HA31 Vol. 30 No 07 Hearst On ~ Le mercredi 4 mai 2005 1,25$ + T.P.S. Budget municipal 2005 PensPensée Le coeur d’une Hausse de taxes de 1,90 % mère est un HEARST(DJ) - Au cours de leur les dépenses s’élèvent également D’autre part, pour ce qui est Pour ce qui est des taxes sco- abîme au fond réunion régulière d’hier (mardi) à 13 678 400 $. des services de protection à la laires pour la prochaine année, soir, les membres du Conseil Puisqu’il est question des population, on observe des hauss- elles demeureront au même taux du quel se municipal de Hearst devaient dépenses, on observe une impor- es en ce qui a trait aux montants qu’en 2004. Les taux des taxes accepter le budget de la Ville de tante diminution au niveau de investis envers la protection con- scolaires ne sont cependant pas trouve toujours Hearst pour l’année 2005. l’administration de la Ville de tre les incendies (207 700 $ com- fixés par la Municipalité.∆ un pardon Cette année, à la recommanda- Hearst, soit près de 400 000 $. parativement à 184 810 $ l’an tion du groupe de travail de Cette baisse est en grande partie dernier) de même que du côté des Note: Consulter la page HA3 finances formé au sein du Conseil attribuable aux rénovations qui services policiers (1 682 000 $ en pour un aperçu plus détaillé des municipal, le budget pour l’année avaient été apportées l’an dernier 2005 comparativement à 1 604 projets que compte réaliser la Honoré de Balzac 2005 est accompagné d’une à l’Hôtel de Ville. -

The Definitive Guide to Sqlite, Second Edition (Expert's Voice In

BOOKS FOR PROFESSIONALS BY PROFESSIONALS® THE EXPERT’S VOICE® IN OPEN SOURCE Companion eBook Available The Definitive Guide to SQLite The Definitive Dear Reader, Outside of the world of enterprise computing there is one database that enables a huge range of software and hardware to flex relational database capabilities, without the baggage and cost of traditional database management systems. Guide to That database is SQLite—an embeddable database with an amazingly small footprint, yet it can handle databases of enormous size. SQLite comes equipped The Definitive Guide to Grant Allen with an array of powerful features available through a host of programming and development environments. It is supported by languages such as C, Java, Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, TCL, and more. The Definitive Guide to SQLite, 2nd Edition is devoted to complete cover- age of the latest version of this powerful database. It offers a thorough over- SQLite view of SQLite’s capabilities and APIs. The book also uses SQLite as the basis for helping newcomers make their first foray into database development. In only a short time you can be writing programs as diverse as a server-side browser plug-in or the next great iPhone or Android application! • You’ll learn about SQLite extensions for C, Java, Perl, PHP, Python, Ruby, and Tcl. • You’ll get solid coverage of SQLite internals. SQLite • You’ll explore developing iOS (iPhone) and Android applications with SQLite. Mike Owens SQLite is the solution chosen for thousands of products around the world, from mobile phones and GPS devices to set-top boxes and web browsers. -

The Penny Stock Trading Sysyem.Pdf

Another Publication of eBookWholesaler Copyright 2002 Donny Lowy Proudly brought to you by DJP SPECIALTIES Email Recommended Resources Web Site Hosting Service Internet Marketing Affiliate Program Table of Contents Preface --- --- P.2 Chapter 1 - What is a Penny Stock? --- --- P. 8 Chapter 2 - The OTC Market --- --- P. 11 Chapter 3 - The Pink Sheets --- --- P.19 Chapter 4 - Research Tools ---- P. 27 Chapter 5 - Financial Fundamentals --- --- P.55 Chapter 6 - Corporate Developments --- --- P.75 Chapter 7 - Turn Around Situations --- --- P.96 Chapter 8 - Special Situations --- --- P.107 Chapter 9 - Insiders --- --- P.116 Chapter 10 - Research --- --- P.129 Chapter 11 - Investor Relations Firms --- --- P.165 Chapter 12 - Negative Situations --- --- P.180 Chapter 13 - Investment Strategies --- --- P.189 Conclusion – P.212 1 Preface This publication is designed to provide accurate and authoritative information in regard to the subject matter covered. It is sold with the understanding that the author is not engaged in rendering legal, accounting, financial, investment, or other professional service. If legal advice or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. The information in this book is only for educational purposes. Welcome to the most comprehensive system on penny stock trading. The goal of this book is to supply the novice investor along with the experienced professional equity trader with all the information he or she will need to be educated in the realm of penny stock trading. This book can be used as an educational totem for those investors who were always curious about trading in penny stocks but did not know where to start. -

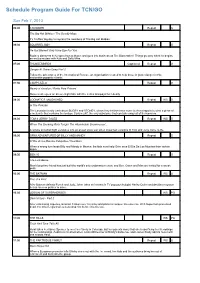

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Feb 7, 2010 06:00 CHOWDER Repeat G The Big Hat Biddies / The Deadly Maze It's Truffles' big day to impress the members of The Big Hat Biddies. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY Repeat G He Got Blame/I Only Have Eye For You Rodney discovers he's impervious to blame and goes into business as The Blametaker! Things go awry when he begins an exclusive deal with Kyle and Salty Mike. 07:00 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Danger At Ocean Deep Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO Repeat G Bearly a Vacation / Radio Free Edward Nurse Leslie goes on an overnight hike with the Jellies and pays for it dearly. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED Repeat WS G In The Pinkster The Loonatics busily track down BUGSY and STONEY, whom they believe have come to Acmetropolis to steal a piece of a meteorite that contains the isotope Curium 247, the only substance that can take away all of their powers. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES Repeat WS G When The Snowing Gets Tough/ The Abominable Snowmouse/... A simple snowball fight escalates into an all-out snow war when snowman versions of Tom and Jerry come to life. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY Repeat G El Dia de los Muertos Estupidos / Heartburn When a wrong turn lands Billy and Mandy in Mexico, the kids must help Grim save El Dia De Los Muertos from certain doom. -

The Show, Er, Um, Article About Nothing (Other Than SEC, CFTC, FINRA, and State Securities Enforcement Actions in August 2020)

NSCPCurrents SEPTEMBER 2020 The Show, er, um, Article About Nothing (other than SEC, CFTC, FINRA, and State Securities Enforcement Actions in August 2020) By Brian Rubin and Alexa Shockley About the Authors: Brian Rubin is a partner at Eversheds Sutherland. He can be reached at [email protected]. Alexa Shockley is an associate at Eversheds Sutherland. She can be reached at [email protected]. 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 NSCP CURRENTS 1 SEPTEMBER 2020 NSCP CURRENTS Jerry: So what’s the deal with this article? You’re telling me that Seinfeld, a show about nothing, was really about securities? Elaine: Get out! Kramer: Giddy-up! Jackie Chiles (the most prominent attorney on Seinfeld) (which isn’t saying much): What Mr. Seinfeld and Ms. Benes are saying, with the able assistance of Mr. Kramer, is this: If you watch this super, stellar, stupendous show with care and calculated calibration, but not with callousness, you too will see that reality. Indeed, in fact, indubitably, Ms. Benes will provide an example. Elaine: See, there was one episode called, “The Stock Tip,” and, yada yada yada, Jerry loses his investment, but George makes a killing. Crazy, right? George: Worlds are colliding! Jerry: Yeah, I guess you could say that.1 Everyone knows that Seinfeld, which premiered 31 summers ago, was one of the most popular television sitcoms ever. It was on the airwaves (remember those?) for nine years, nominated for 68 Emmy Awards, winning ten times, including twice for Outstanding Writing in a Comedy Series, winning twice.2 It was self-identified as a “show about nothing.”3 Indeed, co-creator Larry David “admonished the writing staff that there would be ‘no hugging, no learning’ in the scripts, and there wasn’t. -

Active Portfolio Management a Quantitative Approach for Providing Superior Returns and Controlling Risk

Page iii Active Portfolio Management A Quantitative Approach for Providing Superior Returns and Controlling Risk Richard C. Grinold Ronald N. Kahn SECOND EDITION Page vii CONTENTS Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Chapter 1 1 Introduction Part One Foundations Chapter 2 11 Consensus Expected Returns: The Capital Asset Pricing Model Chapter 3 41 Risk Chapter 4 87 Exceptional Return, Benchmarks, and Value Added Chapter 5 109 Residual Risk and Return: The Information Ratio Chapter 6 147 The Fundamental Law of Active Management Part Two Expected Returns and Valuation Chapter 7 173 Expected Returns and the Arbitrage Pricing Theory Page viii Chapter 8 199 Valuation in Theory Chapter 9 225 Valuation in Practice Part Three Information Processing Chapter 10 261 Forecasting Basics Chapter 11 295 Advanced Forecasting Chapter 12 315 Information Analysis Chapter 13 347 The Information Horizon Part Four Implementation Chapter 14 377 Portfolio Construction Chapter 15 419 Long/Short Investing Chapter 16 445 Transactions Costs, Turnover, and Trading Chapter 17 477 Performance Analysis Page ix Chapter 18 517 Asset Allocation Chapter 19 541 Benchmark Timing Chapter 20 559 The Historical Record for Active Management Chapter 21 573 Open Questions Chapter 22 577 Summary Appendix A 581 Standard Notation Appendix B 583 Glossary Appendix C 587 Return and Statistics Basics Index 591 Page xi PREFACE Why a second edition? Why take time from busy lives? Why devote the energy to improving an existing text rather than writing an entirely new one? Why toy with success? The short answer is: our readers. We have been extremely gratified by Active Portfolio Management's reception in the investment community. -

20 Septembrerd 2006 1,25$ + T.P.S

Une 1976 - 2006 d cinquième Le Nor position pour les Élans à Rouyn LeLVol. 31e No 27 HearstNordN On ~ Le mercredio 20 septembrerd 2006 1,25$ + T.P.S. voir HA22 AL POULIN & associés SERVICES FINANCIERS DEPUIS 1976 Ouvrez votre compte bancaire Avantage Manulife au taux d’intérêt annuel de 3,75%* *TAUX DATÉS DU 6 SEPTEMBRE 2006. L’INTÉRÊT EST CALCULÉ À LA FERMETURE DE LA BALANCE JOURNALIÈRE ET PAYÉ MENSUELLEMENT. TAUX SONT SUJETS AUX CHANGEMENTS. 133, RUE SPRUCE, SUD-TIMMINS 705-266-5284 AU SERVICE DES CLIENTS DEPUIS 1976 Pensée de la semaine Je me presse de rire de tout, de peur d’être obligé d’en pleurer. Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais C’est dimanche dernier, sous une pluie battante, qu’avait lieu la 26e édition de la Course Terry Fox. Malgré le mauvais temps, ils étaient une dizaine à prendre le départ pour le parcours de 10 kilomètres dans les rues de la communauté. On reconnaît : le maire Roger Sigouin, Suzanne Gaudreault, Kimberly Lapierre, Johanie Gaudreault, Arianne Gaudreault, Katelyn Wickman, MacKenzie Wickman, Linda McNeil, José Léger, Agathe Breton et Mario Ouellet. Photo disponible au journal Le Nord/CP MERCREDI Nuageux avec bruine Un grand succès Max 8 PdP 40% JEUDI pour la conférence Ciel variable Min 5; Max 9 PdP 30% de l’AFMO VENDREDI Nuageux avec HA02 éclaircies et averses Min 7; Max 10 PdP 60% SAMEDI Festival national Eva Gosselin en Nuageux avec averses Min 6; Max 9 PdP 40% de l’humour de lice pour un autre DIMANCHE Nuageux Hearst mandat Min 5; Max 9 PdP 30% LUNDI Ensoleillé avec passages nuageux Min 3; Max 16 PdP 10% HA11 HA10 Un nouveau virage anime la 17e conférence annuelle de l’AFMO HEARST(AB) – La bio- démontré qu’elle pouvait accom- cophones, Madeleine Meilleur, a que ces derniers ont eu droit à un «Une fois qu’il ne restait plus de économie, les arts et la forêt ont plir de grandes choses.» procédé au dévoilement d’une mini-spectacle mettant en vedette chambres de motel, la commu- dominé la 17e conférence La bio-économie a retenu plaque soulignant la présence Véronic Dicaire. -

Great Quotes

Great Quotes Brought to you by SeinfeldQuotes.net Jerry: House in the Hamptons? George: Well, you know, I've been lying about my income for a few years; I figured I could afford a fake house in the Hamptons. -from “The Wizard” Kramer: Newman and I are reversing the peepholes on our door so you can see in. Elaine: Why? Newman: To prevent an ambush. Kramer: Yeah, so now I can peek to see if anyone is waiting to jack me with a sock full of pennies. Jerry: But then anyone can just look in and see you. Kramer: Our policy is, we're comfortable with our bodies. You know, if someone wants to help themselves to an eyeful, well, we say "Enjoy the show." -from “The Reverse Peephole” Jerry: His name is Joel Horneck. He lived, like, three houses down from me when I grew up. He had a Ping Pong table. We were friends. Should I suffer the rest of my life because I like to play Ping Pong? I was ten! I would've been friends with Stalin if he had a Ping Pong table! -from “Male Unbonding” Kramer: ¿Como se dice.. waterbed? -from “The Busboy” Kramer: Jerry, I'm sorry… You have insurance, right? Jerry: No. Kramer: How could you not have insurance? Jerry: Because I spent my money on the Klapco D29! It's the most impenetrable lock in the market today! It has only one design flaw. The door… must be closed! -from “The Robbery” Elaine: Ya know, its not fair people are seated first-come-first-serve. -

Program Guide Report

Schedule Program Guide For TCN/GO Sun Nov 1, 2009 06:00 CHOWDER G The Thrice Cream Man/The Flibber-Flabber Diet Mung tries to find a way to break Chowder's obsession with thrice cream, so he gets a real life Thrice Cream Man to visit. After a day of fun, Chowder's new friend turns out to be a nightmare. 06:30 SQUIRREL BOY G The Greatest Schmo on Earth/ Outta Sight Rodney's special time at the circus with Darlene is ruined by the arrival of Rodney's Cousin Eddie, who in addition to being arrogant and self-centered can also fly. 07:00 KIDS WB SUNDAY WS G 07:05 THUNDERBIRDS Captioned Repeat G Operation Crash-Dive Part 2 Follow the adventures of the International Rescue, an organisation created to help those in grave danger in this marionette puppetry classic. 07:30 CAMP LAZLO G Snow Beans/ Irreconcilable Dungferences The Beans Scouts and the Squirrel Scouts go skiing, and Lazlo and Lumpus discover that the mountain isn't big enough for the both of them. 08:00 LOONATICS UNLEASHED WS G Apocalypso The Loonatics vacation on a tropical island, only to discover that it's been colonized by a race of beautiful women called the APOCAZONS. 08:30 TOM & JERRY TALES WS G Declaration Of Independunce/ Kitty Hawked/ 24 Karat Kat In Colonial America, Tom stuffs Jerry into a paper airplane made out of the Declaration of Independence, and frantically tries to get it back before Thomas Jefferson kicks his tail. 09:00 GRIM ADVENTURES OF BILLY AND MANDY G Wrath of the Spider Queen (Part Two) When the Grim Reaper's past comes back to haunt him, Billy & Mandy must join forces with their greatest enemies to save the day.