Access to Electronic Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

Japan, Russia and the "Northern Territories" Dispute : Neighbors in Search of a Good Fence

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2002-09 Japan, Russia and the "northern territories" dispute : neighbors in search of a good fence Morris, Gregory L. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/4801 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL Monterey, California THESIS JAPAN, RUSSIA AND THE “NORTHERN TERRITORIES” DISPUTE: NEIGHBORS IN SEARCH OF A GOOD FENCE by Gregory L. Morris September, 2002 Thesis Advisors: Mikhail Tsypkin Douglas Porch Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED September 2002 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE: Japan, Russia And The “Northern Territories” Dispute: 5. FUNDING NUMBERS Neighbors In Search Of A Good Fence n/a 6. AUTHOR(S) LT Gregory L. -

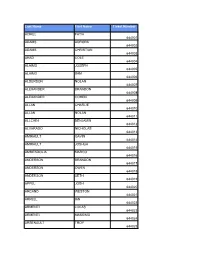

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS AURORA 644002 ADAMS CHRISTIAN 644003 AHAD COLE 644004 ALAIMO JOSEPH 644005 ALAIMO SAM 644006 ALDERSON NOLAN 644007 ALEXANDER BRANDON 644008 ALEXANDER COHEN 644009 ALLAN CHARLIE 644010 ALLAN NOLAN 644011 ALLCHIN BENJAMIN 644012 ALVARADO NICHOLAS 644013 AMIRAULT GAVIN 644014 AMIRAULT JOSHUA 644015 AMMENDOLIA MARCO 644016 ANDERSON BRANDON 644017 ANDERSON OWEN 644018 ANDERSON SETH 644019 APPEL JOSH 644020 ARCAND WESTON 644021 ARKELL IAN 644022 ARMENTI LUCAS 644023 ARMENTI MASSIMO 644024 ARSENAULT TROY 644025 ASIS GRAYSON 644026 ASSELIN WYATT 644027 ATHERTON DATON 644028 AZEM SIMMONS BLAZE 644029 AZEM SIMMONS JADE 644030 AZEM SIMMONS KYLEN 644031 BACH AYDEN 644032 BAIOCCO MARIO 644033 BAIRD EVAN 644034 BAIRD LIAM 644035 BAIRD OWEN 644036 BAKER BENNETT 644037 BALL DANIEL 644038 BALL MATTHEW 644039 BANDERS LEO 644040 BANNISTER DYLAN 644041 BANNISTER LANDEN 644042 BARCHIESI BRYNN 644043 BARCHIESI SLOAN 644044 BARCLAY LONDON 644045 BARKER CHARLIE 644046 BARLOW HOLDEN 644047 BARNHARDT JAMES 644048 BARNHARDT WILLIAM 644049 BARRINGTON DYLAN 644050 BARRON LUCAS 644051 BARRY KELDON 644052 BARRY NOLAN 644053 BARRY TYSEN 644054 BARTON BROGAN 644055 BARTON NOLAN 644056 BASS-MELDRUM CALEB 644057 BAUGHMAN BRICE 644058 BAUGHMAN BRODY 644059 BEAMISH LEVI 644060 BEAMISH ZACK 644061 BEAUVAIS NOAH 644062 BEAVER BENJAMIN 644063 BEAVER JOSHUA 644064 BECK ERIC 644065 BELANGER BEAU 644066 BELANGER ETHAN 644067 BELFORD LINCOLN 644068 BENNETT COOPER 644069 BENSON JACK 644070 BERECZ MAX 644071 BERGEN CONNELL -

Japan Geoscience Union Meeting 2009 Presentation List

Japan Geoscience Union Meeting 2009 Presentation List A002: (Advances in Earth & Planetary Science) oral 201A 5/17, 9:45–10:20, *A002-001, Science of small bodies opened by Hayabusa Akira Fujiwara 5/17, 10:20–10:55, *A002-002, What has the lunar explorer ''Kaguya'' seen ? Junichi Haruyama 5/17, 10:55–11:30, *A002-003, Planetary Explorations of Japan: Past, current, and future Takehiko Satoh A003: (Geoscience Education and Outreach) oral 301A 5/17, 9:00–9:02, Introductory talk -outreach activity for primary school students 5/17, 9:02–9:14, A003-001, Learning of geological formation for pupils by Geological Museum: Part (3) Explanation of geological formation Shiro Tamanyu, Rie Morijiri, Yuki Sawada 5/17, 9:14-9:26, A003-002 YUREO: an analog experiment equipment for earthquake induced landslide Youhei Suzuki, Shintaro Hayashi, Shuichi Sasaki 5/17, 9:26-9:38, A003-003 Learning of 'geological formation' for elementary schoolchildren by the Geological Museum, AIST: Overview and Drawing worksheets Rie Morijiri, Yuki Sawada, Shiro Tamanyu 5/17, 9:38-9:50, A003-004 Collaborative educational activities with schools in the Geological Museum and Geological Survey of Japan Yuki Sawada, Rie Morijiri, Shiro Tamanyu, other 5/17, 9:50-10:02, A003-005 What did the Schoolchildren's Summer Course in Seismology and Volcanology left 400 participants something? Kazuyuki Nakagawa 5/17, 10:02-10:14, A003-006 The seacret of Kyoto : The 9th Schoolchildren's Summer Course inSeismology and Volcanology Akiko Sato, Akira Sangawa, Kazuyuki Nakagawa Working group for -

The East China Sea Disputes: History, Status, and Ways Forward

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Almae Matris Studiorum Campus Asian Perspective 38 (2014), 183 –218 The East China Sea Disputes: History, Status, and Ways Forward Mark J. Valencia The dispute over ownership of islands, maritime boundaries, juris - diction, perhaps as much as 100 billion barrels of oil equivalent, and other nonliving and living marine resources in the East China Sea continues to bedevil China-Japan relations. Historical and cultural factors, such as the legacy of World War II and burgeoning nation - alism, are significant factors in the dispute. Indeed, the dispute seems to have become a contest between national identities. The approach to the issue has been a political dance by the two coun - tries: one step forward, two steps back. In this article I explain the East China Sea dispute, explore its effect on China-Japan relations, and suggest ways forward. KEYWORDS : China-Japan relations, terri - torial disputes, nationalism. RELATIONS BETWEEN THE PEOPLE ’S REPUBLIC OF CHINA (PRC) AND Japan are perhaps at their lowest ebb since relations were for - mally reestablished in 1972. The d ispute over islets and maritime claims in the East China Sea has triggered m uch of this recent deterioration . Because of the dispute, China has canceled or refused many exchanges and meetings of high-level officials, including summit meetings. In fact, China has said that a summit meeting cannot take place until or unless Japan acknowledges that a dispute over sovereignty and jurisdiction exists, something Japan has thus far refused to do. -

The Division System in Crisis Essays on Contemporary Korea Paik Nak-Chung

The Division System in Crisis Essays on Contemporary Korea Paik Nak-chung Foreword by Bruce Cumings Translated by Kim Myung-hwan, Sol June-Kyu,Song Seung-cheol, and Ryu Young-joo, with the collaboration of the author Published in association with the University of California Press Paik Nak-chung is one of Korea’s most incisive contemporary public intellec- tuals. By training a literary scholar, he is perhaps best known as an eloquent cultural and political critic. This volume represents the first book-length col- lection of his writings in English. Paik’s distinctive theme is the notion of a “division system” on the Korean peninsula, the peculiar geopolitical and cultural logic by which one nation continues to be divided into two states, South and North. Identifying a single structure encompassing both Koreas and placing it within the framework of the contemporary world-system, Paik shows how this reality has insinuated itself into virtually every corner of modern Korean life. “A remarkable combination of scholar, author, critic, and activist, Paik Nak- chung carries forward in our time the ancient Korean ideal of marrying ab- stract learning to the daily, practical problems of the here and now. In this book he confronts no less than the core problem facing the Korean people since the mid-twentieth century: the era of national division, of two Koreas, an anomaly for a people united across millennia and who formed the basic sinews of their nation long before European nation-states began to develop.” BRUCE CUMINGS, from the foreword PAIK NAK-CHUNG is emeritus professor of English literature at Seoul National University. -

List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co

List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co. Name First Initial Claim 20TH CENTURY FOX HOME ENTERTAINMENT $63.73 AASMAN T $20.41 ABBAS H $15.22 ABBOTT R $54.60 ABBOTT T $11.48 ABBOTT B $4.83 ABBOTT J $4.17 ABBOTT S $0.80 ABBOTT Y $0.37 ABBOTT S $0.36 ABBOTT J $0.36 ABDEL-SAYED C $30.16 ABDULLAH R $0.40 ABELL PEST CONTROL INC $598.86 ABILA M $31.53 ABLETT J $2.28 ABOUD M $37.88 ABOUGHOURY E $13.68 ABRAHAM S $69.67 ABRAHAM D $55.16 ABRAHAM S $31.47 ABRAHAM B $6.69 ABRAHAMSE R $6.36 ABRAHAMSE P $1.25 ABRAM R $1.14 ABRAMS C $2.50 ABURROW K $0.78 ACCARDI S $0.56 ACCORDINO M $1.77 ACETI E $16.08 ACEVEDO SALINAS R $1.70 ACHESON T $173.79 ACHILLES T $11.74 ACHTZEHNTER T $0.58 ACKAH L $12.08 ACKER J $34.31 ACKERS M $39.62 ACKLAND D $5.00 ACKROYD A $0.24 ACORN E $1.74 ACORN C $0.31 ACOSTA E $3.91 ACOSTA M $2.50 ACS C $159.33 ACTON G $37.21 ACUNA J $0.26 ADAIR M $15.94 ADAIR K $12.24 ADAMS J $104.22 Page 1 List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co. Name First Initial Claim ADAMS J $38.76 ADAMS E $37.53 ADAMS D $34.62 ADAMS S $34.32 ADAMS M $30.98 ADAMS J $20.87 ADAMS T $20.15 ADAMS M $15.03 ADAMS E $9.73 ADAMS D $7.80 ADAMS D $7.68 ADAMS A $4.82 ADAMS N $2.50 ADAMS T $1.37 ADAMS K $1.14 ADAMS K $0.81 ADAMS L $0.79 ADAMS W $0.59 ADAMS A $0.24 ADAMS M $0.22 ADAMS S $0.20 ADAMS L $0.13 ADAMS D $0.08 ADAMS B $0.04 ADAMS MACKIE P $8.40 ADAMSKI J $2.18 ADAMSON C $4.25 ADAMSON D $2.47 ADCOCK C $15.50 ADDEH G $67.18 ADDERLEY G $2.25 ADDISON D $89.64 ADDY A $7.37 ADER K $42.17 ADJEI J $1.74 ADJEI C $0.19 ADJELEIAN H $2.06 ADRAIN S $0.13 ADRIAENSEN J $23.67 ADRIAN S $52.41 ADSHEAD J $29.67 AEICHELE S $6.00 AFFARY A $6.80 AFFILIATE FUTURE INC. -

Disputes Over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected]

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Communication Faculty Publications School of Communication 6-2014 Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Dexin Tian Savannah College of Art and Design, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub Part of the Communication Commons Recommended Citation Chao, Chin-Chung and Tian, Dexin, "Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies" (2014). Communication Faculty Publications. 85. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/commfacpub/85 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Communication at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Communication Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Journal of International Relations and Foreign Policy June 2014, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 19-47 ISSN: 2333-5866 (Print), 2333-5874 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development Disputes over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands: Communication Tactics and Grand Strategies Chin-Chung Chao1 and Dexin Tian2 Abstract This study explores the communication tactics and grand strategies of each of the involved parties in the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands disputes. Under the theoretical balance between liberal -

US Ambiguity on the Senkakus' Sovereignty

Naval War College Review Volume 72 Article 8 Number 3 Summer 2019 2019 Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty Robert C. Watts IV Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Watts, Robert C. IV (2019) "Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty," Naval War College Review: Vol. 72 : No. 3 , Article 8. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol72/iss3/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Watts: Origins of a “Ragged Edge”—U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovere ORIGINS OF A “RAGGED EDGE” U.S. Ambiguity on the Senkakus’ Sovereignty Robert C. Watts IV n May 15, 1972, the United States returned Okinawa and the other islands in the Ryukyu chain to Japan, culminating years of negotiations that some have 1 Ohailed as “an example of diplomacy at its very best�” As a result, Japan regained territories it had lost at the end of World War II, while the United States both retained access to bases on Okinawa and reaffirmed strategic ties with Japan� One detail, however, complicates this win-win assessment� At the same time, Japan also regained administrative control over the Senkaku, or Diaoyu, Islands, a group of uninhabited—and uninhabitable—rocky outcroppings in the East China Sea�2 By 1972, both the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC) on Taiwan also had claimed these islands�3 Despite passing con- trol of the Senkakus to Japan, the United States expressed no position on any of the competing claims to the islands, including Japan’s� This choice—not to weigh in on the Senkakus’ sovereignty—perpetuated Commander Robert C. -

Denationalizing International Law in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Island Dispute

THE PACIFIC WAR, CONTINUED: DENATIONALIZING INTERNATIONAL LAW IN THE SENKAKU/DIAOYU ISLAND DISPUTE Joseph Jackson Harris* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................... 588 II. BACKGROUND ................................................................................. 591 A. Each State’s Historical Links to the Islands............................. 591 B. A New Dimension to the Dispute: Economic Opportunities Emerge ..................................................................................... 593 III. INTERNATIONAL LAW GOVERNING THE DISPUTE .......................... 594 A. Territorial Acquisition and International Rules of Sovereignty ............................................................................... 594 B The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and Exclusive Economic Rights ...................................................... 596 IV. COMPETING LEGAL CLAIMS AND THE INTERACTION OF INTERNATIONAL LAW, NATIONALIST HISTORY, AND STATE ECONOMIC INTERESTS .................................................................... 596 A. Problems Raised By the Applicable International Law ........... 596 B. The Roots of the Conflict in the Sino-Japanese Wars .............. 597 V. ALTERNATIVE RULES THAT MIGHT PROVIDE MORE STABLE GROUNDS FOR RESOLUTION OF THE DISPUTE ................................ 604 A. Exclusive Economic Zones: Flexibility over Brittleness .......... 608 B. Minimal Contacts Baseline and Binding Arbitration ............... 609 C. The -

Comparative Connections

Pacific Forum CSIS Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations edited by Brad Glosserman Vivian Brailey Fritschi 3rd Quarter 2003 Vol. 5, No. 3 October 2003 www.csis.org/pacfor/ccejournal.html Pacific Forum CSIS Based in Honolulu, Hawaii, the Pacific Forum CSIS operates as the autonomous Asia-Pacific arm of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1975, the thrust of the Forum’s work is to help develop cooperative policies in the Asia-Pacific region through debate and analyses undertaken with the region’s leaders in the academic, government, and corporate arenas. The Forum’s programs encompass current and emerging political, security, economic/business, and oceans policy issues. It collaborates with a network of more than 30 research institutes around the Pacific Rim, drawing on Asian perspectives and disseminating its projects’ findings and recommendations to opinion leaders, governments, and publics throughout the region. An international Board of Governors guides the Pacific Forum’s work; it is chaired by Brent Scowcroft, former Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs. The Forum is funded by grants from foundations, corporations, individuals, and governments, the latter providing a small percentage of the forum’s $1.2 million annual budget. The Forum’s studies are objective and nonpartisan and it does not engage in classified or proprietary work. Comparative Connections A Quarterly E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Edited by Brad Glosserman and Vivian Brailey Fritschi Volume 5, Number 3 Third Quarter 2003 Honolulu, Hawaii October 2003 Comparative Connections A Quarterly Electronic Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Bilateral relationships in East Asia have long been important to regional peace and stability, but in the post-Cold War environment, these relationships have taken on a new strategic rationale as countries pursue multiple ties, beyond those with the U.S., to realize complex political, economic, and security interests. -

N. Carolina Textile Giant Closes, 7,500 out of A

· AUSTRALIA $3.00 · CANADA $2.50 · FRANCE 2.00 EUROS · ICELAND KR200 · NEW ZEALAND $3.00 · SWEDEN KR15 · UK £1.00 · U.S. $1.50 INSIDE U.S. youth visiting Cuba meet revolutionary social workers — PAGE 7 A SOCIALIST NEWSWEEKLY PUBLISHED IN THE INTERESTS OF WORKING PEOPLE VOL. 67/NO. 29 AUGUST 25, 2003 N. Carolina textile giant Nicaraguan peasants closes, 7,500 out of a job march for BY LOUIS TURNER their union, UNITE, for KANNAPOLIS, North Carolina—Pil- information and guid- lowtex Corp., one of the largest U.S. textile ance. land, credit manufacturers, announced July 30 that it These workers scored BY SETH GALINSKY was closing 16 plants in the United States a victory for all labor MIAMI—Several thousand peasants and and Canada. The closures will throw more four years ago when farm workers began a 75-mile-long march than 7,500 workers onto the rolls of the un- they won representation on July 29 from Matagalpa, the coffee- employed. The textile giant fi led for Chapter by the Union of Need- growing center of Nicaragua, to Managua, 11 bankruptcy and plans to liquidate all its letrades, Industrial and the country’s capital. They demanded land, assets. Textile Employees (now cheap credit, and government aid for rural Pillowtex, known for the brand names UNITE). After waging toilers hard hit by the world-wide drop in Fieldcrest Cannon and Royal Velvet, fi led a 25-year fight to get coffee prices and a drought. At the same for bankruptcy in 2001. At that time, it the union in, workers time, some 6,000 peasants occupied farms closed several mills and laid off thousands won their fi rst contract and waged sit-down strikes and other pro- of workers.