Linguistyka Silesiana 39.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aalseth Aaron Aarup Aasen Aasheim Abair Abanatha Abandschon Abarca Abarr Abate Abba Abbas Abbate Abbe Abbett Abbey Abbott Abbs

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 35 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 306 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 98.500 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

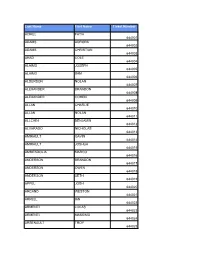

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS

Last Name First Name Ticket Number ACIKEL FATIH 644001 ADAMS AURORA 644002 ADAMS CHRISTIAN 644003 AHAD COLE 644004 ALAIMO JOSEPH 644005 ALAIMO SAM 644006 ALDERSON NOLAN 644007 ALEXANDER BRANDON 644008 ALEXANDER COHEN 644009 ALLAN CHARLIE 644010 ALLAN NOLAN 644011 ALLCHIN BENJAMIN 644012 ALVARADO NICHOLAS 644013 AMIRAULT GAVIN 644014 AMIRAULT JOSHUA 644015 AMMENDOLIA MARCO 644016 ANDERSON BRANDON 644017 ANDERSON OWEN 644018 ANDERSON SETH 644019 APPEL JOSH 644020 ARCAND WESTON 644021 ARKELL IAN 644022 ARMENTI LUCAS 644023 ARMENTI MASSIMO 644024 ARSENAULT TROY 644025 ASIS GRAYSON 644026 ASSELIN WYATT 644027 ATHERTON DATON 644028 AZEM SIMMONS BLAZE 644029 AZEM SIMMONS JADE 644030 AZEM SIMMONS KYLEN 644031 BACH AYDEN 644032 BAIOCCO MARIO 644033 BAIRD EVAN 644034 BAIRD LIAM 644035 BAIRD OWEN 644036 BAKER BENNETT 644037 BALL DANIEL 644038 BALL MATTHEW 644039 BANDERS LEO 644040 BANNISTER DYLAN 644041 BANNISTER LANDEN 644042 BARCHIESI BRYNN 644043 BARCHIESI SLOAN 644044 BARCLAY LONDON 644045 BARKER CHARLIE 644046 BARLOW HOLDEN 644047 BARNHARDT JAMES 644048 BARNHARDT WILLIAM 644049 BARRINGTON DYLAN 644050 BARRON LUCAS 644051 BARRY KELDON 644052 BARRY NOLAN 644053 BARRY TYSEN 644054 BARTON BROGAN 644055 BARTON NOLAN 644056 BASS-MELDRUM CALEB 644057 BAUGHMAN BRICE 644058 BAUGHMAN BRODY 644059 BEAMISH LEVI 644060 BEAMISH ZACK 644061 BEAUVAIS NOAH 644062 BEAVER BENJAMIN 644063 BEAVER JOSHUA 644064 BECK ERIC 644065 BELANGER BEAU 644066 BELANGER ETHAN 644067 BELFORD LINCOLN 644068 BENNETT COOPER 644069 BENSON JACK 644070 BERECZ MAX 644071 BERGEN CONNELL -

List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co

List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co. Name First Initial Claim 20TH CENTURY FOX HOME ENTERTAINMENT $63.73 AASMAN T $20.41 ABBAS H $15.22 ABBOTT R $54.60 ABBOTT T $11.48 ABBOTT B $4.83 ABBOTT J $4.17 ABBOTT S $0.80 ABBOTT Y $0.37 ABBOTT S $0.36 ABBOTT J $0.36 ABDEL-SAYED C $30.16 ABDULLAH R $0.40 ABELL PEST CONTROL INC $598.86 ABILA M $31.53 ABLETT J $2.28 ABOUD M $37.88 ABOUGHOURY E $13.68 ABRAHAM S $69.67 ABRAHAM D $55.16 ABRAHAM S $31.47 ABRAHAM B $6.69 ABRAHAMSE R $6.36 ABRAHAMSE P $1.25 ABRAM R $1.14 ABRAMS C $2.50 ABURROW K $0.78 ACCARDI S $0.56 ACCORDINO M $1.77 ACETI E $16.08 ACEVEDO SALINAS R $1.70 ACHESON T $173.79 ACHILLES T $11.74 ACHTZEHNTER T $0.58 ACKAH L $12.08 ACKER J $34.31 ACKERS M $39.62 ACKLAND D $5.00 ACKROYD A $0.24 ACORN E $1.74 ACORN C $0.31 ACOSTA E $3.91 ACOSTA M $2.50 ACS C $159.33 ACTON G $37.21 ACUNA J $0.26 ADAIR M $15.94 ADAIR K $12.24 ADAMS J $104.22 Page 1 List of Creditors of DB Media Distribution (Canada) Last Name / Co. Name First Initial Claim ADAMS J $38.76 ADAMS E $37.53 ADAMS D $34.62 ADAMS S $34.32 ADAMS M $30.98 ADAMS J $20.87 ADAMS T $20.15 ADAMS M $15.03 ADAMS E $9.73 ADAMS D $7.80 ADAMS D $7.68 ADAMS A $4.82 ADAMS N $2.50 ADAMS T $1.37 ADAMS K $1.14 ADAMS K $0.81 ADAMS L $0.79 ADAMS W $0.59 ADAMS A $0.24 ADAMS M $0.22 ADAMS S $0.20 ADAMS L $0.13 ADAMS D $0.08 ADAMS B $0.04 ADAMS MACKIE P $8.40 ADAMSKI J $2.18 ADAMSON C $4.25 ADAMSON D $2.47 ADCOCK C $15.50 ADDEH G $67.18 ADDERLEY G $2.25 ADDISON D $89.64 ADDY A $7.37 ADER K $42.17 ADJEI J $1.74 ADJEI C $0.19 ADJELEIAN H $2.06 ADRAIN S $0.13 ADRIAENSEN J $23.67 ADRIAN S $52.41 ADSHEAD J $29.67 AEICHELE S $6.00 AFFARY A $6.80 AFFILIATE FUTURE INC. -

S:\FULLCO~1\HEARIN~1\Committee Print 2018\Henry\Jan. 9 Report

Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. 1 115TH CONGRESS " ! S. PRT. 2d Session COMMITTEE PRINT 115–21 PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY A MINORITY STAFF REPORT PREPARED FOR THE USE OF THE COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JANUARY 10, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Foreign Relations Available via World Wide Web: http://www.gpoaccess.gov/congress/index.html U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 28–110 PDF WASHINGTON : 2018 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. 9 REPORT FOREI-42327 with DISTILLER seneagle Embargoed for Media Publication / Coverage until 6:00AM EST Wednesday, January 10. COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS BOB CORKER, Tennessee, Chairman JAMES E. RISCH, Idaho BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland MARCO RUBIO, Florida ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey RON JOHNSON, Wisconsin JEANNE SHAHEEN, New Hampshire JEFF FLAKE, Arizona CHRISTOPHER A. COONS, Delaware CORY GARDNER, Colorado TOM UDALL, New Mexico TODD YOUNG, Indiana CHRISTOPHER MURPHY, Connecticut JOHN BARRASSO, Wyoming TIM KAINE, Virginia JOHNNY ISAKSON, Georgia EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts ROB PORTMAN, Ohio JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon RAND PAUL, Kentucky CORY A. BOOKER, New Jersey TODD WOMACK, Staff Director JESSICA LEWIS, Democratic Staff Director JOHN DUTTON, Chief Clerk (II) VerDate Mar 15 2010 04:06 Jan 09, 2018 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 S:\FULL COMMITTEE\HEARING FILES\COMMITTEE PRINT 2018\HENRY\JAN. -

Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation

Disclosure for 2012 under the Public Sector Salary Disclosure Act, 1996 Hydro One and Ontario Power Generation This category includes Hydro One Inc., Ontario Power Generation Inc. and their subsidiaries. Divulgation pour 2012 en vertu de la Loi de 1996 sur la divulgation des traitements dans le secteur public Hydro One et Ontario Power Generation Cette catégorie englobe Hydro One Inc., Ontario Power Generation Inc. et leurs filiales. Taxable Surname/Nom de Given Name/ Salary Paid/ Benefits/ Employer/Employeur famille Prénom Position/Poste Traitement Avant. impos. Hydro One ABBOTT BRAD Regional Maintainer - Lines Union Trades Supervisor 3$129,794.86 $1,403.37 Hydro One ABBOTT MARK Customer & Business Services Manager $128,716.44 $1,158.84 Hydro One ABRAMS DONALD Line Subforeperson Construction $103,529.82 $0.00 Hydro One ABUJAFAR MOHAMMAD Senior Protection & Control Engineer/Officer $104,748.38 $694.51 Hydro One ACTON ROB Controller $128,327.49 $1,446.58 Hydro One ADAM JOCELYNE Regional Maintainer II - Electrical $103,872.58 $1,783.47 Hydro One ADAMS CHAD Regional Maintainer II - Lines $117,823.68 $1,322.46 Hydro One ADAMS CLINT Area Forestry Technician $101,386.47 $1,358.13 Hydro One ADAMS DAN Regional Maintainer I - Lines $113,520.18 $1,354.65 Hydro One ADAMS DAVID Customer Care Director $185,590.96 $1,081.06 Hydro One ADAMS GREG Regional Maintainer - Lines Union Trades Supervisor 2$151,060.68 $1,458.18 Hydro One ADAMS STEPHEN Distribution Technician (Forestry) $117,624.13 $1,430.34 Hydro One ADLINGTON MIKE Regional Maintainer 1 - Electrical -

Last Name First Name Middle Name City State NPI Amount AARONS

Last Name First Name Middle Name City State NPI Amount AARONS SCOTT PAUL BAYTOWN TX 1841386919 14.64 AARONSON BETH DANBURY CT 1417991456 17.18 ABANG ANTHONY E ELIZABETHTOWN KY 1548250525 15.7 ABBAS HUMAYUN MODESTO CA 1336136548 14.01 ABBAS JALAL M SURPRISE AZ 1205895034 11.55 ABBASINEJAD MEISHA KAMA FAYETTEVILLE NC 1982646352 41.81 ABBEY DAVID MICHAEL FORT COLLINS CO 1568483196 26.17 ABBOTT JOHN THOMAS FAYETTEVILLE GA 1861679805 17.67 ABBOTT LISA G RENO NV 1609883701 6833.69 ABDEL HALIM AYMAN MOHAMED FORT WORTH TX 1093806697 14.23 ABDELHADY MAZEN DETROIT MI 1669771507 36.69 ABDELMESSIH MOURAD NEWARK OH 1184628950 51.33 ABDELMESSIH NIVEEN K GLENDALE CA 1922071059 17.54 ABDELSAYED GEORGE LOS ANGELES CA 1568721843 5600 ABDULIAN MICHAEL H LOS ANGELES CA 1649469628 12.66 ABDULLAH AZRA INDIANAPOLIS IN 1063468916 11.96 ABDULLAH GHAZANFAR SYED BRONX NY 1639108137 18.18 ABDULMASSIH ABDULMASSIH SKOKIE IL 1629045778 10.49 ABDUS-SALAAM SHARIF ASHANTI MEMPHIS TN 1134386592 125 ABDY VICTOR A WAYNE NJ 1164446795 11.47 ABEDMAHMOUD ISSA HERRIN IL 1528042975 25.34 ABELES ARYEH M. MERIDEN CT 1285737155 45.52 ABELES MICHA MERIDEN CT 1497751556 45.52 ABELL BRIAN E AUGUSTA GA 1215081534 18.43 ABERNATHY BRETT B. DENVER CO 1437106028 32.51 ABIDI SAIYID MANZOOR MAPLE SHADE NJ 1508816729 101.65 ABOUHOSSEIN AHMAD DAYTON OH 1487693156 56.07 ABOUMATAR SAMI MOHAMAD AUSTIN TX 1760445407 19.48 ABRAHAM BACHU MOUNT PLEASANT MI 1225045024 10.19 ABRAHAM ROBERT JONESBORO AR 1780641563 15.63 ABRAHAM SUNIL VARKEY SCHENECTADY NY 1801080890 37.03 ABRAHAM WILLIAM L TUCSON AZ -

April 30, 2016 | Michigan Stadium SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY of MICHIGAN April 30, 2016 10:00 A.M

April 30, 2016 | Michigan Stadium SPRING COMMENCEMENT UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN April 30, 2016 10:00 a.m. This program includes a list of the candidates for degrees to be granted upon completion of formal requirements. Candidates for graduate degrees are recommended jointly by the Executive Board of the Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies and the faculty of the school or college awarding the degree. Following the School of Graduate Studies, schools are listed in order of their founding. Candidates within those schools are listed by degree then by specialization, if applicable. Horace H. Rackham School of Graduate Studies ..................................................................................................20 College of Literature, Science, and the Arts ............................................................................................................31 Medical School ......................................................................................................................................................51 Law School ............................................................................................................................................................52 School of Dentistry ................................................................................................................................................54 College of Pharmacy ..............................................................................................................................................55 -

Plasma Proteins and Their Interaction with Synthetic Polymers at the Air-Water Interface

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2013 Plasma Proteins and Their interaction With Synthetic Polymers at the Air-Water interface Zhengzheng Liao University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Physical Chemistry Commons Recommended Citation Liao, Zhengzheng, "Plasma Proteins and Their interaction With Synthetic Polymers at the Air-Water interface" (2013). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 774. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/774 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/774 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Plasma Proteins and Their interaction With Synthetic Polymers at the Air-Water interface Abstract The adsorption of proteins and synthetic polymers at the air-water interface (AWI) has broad significance in biomedicine and biotechnology. Protein behavior at the AWI can be guided to control the structure of the two-dimensional biopolymer film. In addition, synthetic polymers affect how plasma proteins act on implant or drug carrier surfaces, and can also decrease the potential for gas embolism. In this thesis, fluorescence microscopy was applied in combination with tensiometry and atomic force microscopy to study plasma proteins at the AWI alone and under the effect of synthetic polymers. First, the morphology of serum albumin layer controlled by the solution conditions was explored by fluorescence microscopy. Heterogeneity at the micron scale was observed for the protein film during adsorption and at educedr concentrations. Moreover, the competition for interfacial area between Pluronic surfactant F-127 and fibrinogen or serum albumin was studied by semi-quantitative confocal fluorescence methods. -

Gene Regulation in Response to DNA Damage☆

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1819 (2012) 154–165 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Biochimica et Biophysica Acta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/bbagrm Gene regulation in response to DNA damage☆ Anja Mannuss, Oliver Trapp, Holger Puchta ⁎ Botanical Institute II, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany article info abstract Article history: To deal with different kinds of DNA damages, there are a number of repair pathways that must be carefully Received 17 June 2011 orchestrated to guarantee genomic stability. Many proteins that play a role in DNA repair are involved in Received in revised form 25 July 2011 multiple pathways and need to be tightly regulated to conduct the functions required for efficient repair of Accepted 4 August 2011 different DNA damage types, such as double strand breaks or DNA crosslinks caused by radiation or Available online 16 August 2011 genotoxins. While most of the factors involved in DNA repair are conserved throughout the different kingdoms, recent results have shown that the regulation of their expression is variable between different Keywords: DNA repair organisms. In the following paper, we give an overview of what is currently known about regulating factors Homologous recombination and gene expression in response to DNA damage and put this knowledge in context with the different DNA NHEJ repair pathways in plants. This article is part of a Special Issue entitled: Plant gene regulation in response to ATM abiotic stress. ATR © 2011 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. BER 1. Introduction comparing microarray studies of wildtype plants and plants with mutations in their DNA repair genes [20–23]. -

Agenda Guy M

BRIAN SANDOVAL Governor MEMBERS AGENDA GUY M. WELLS, CHAIRMAN THOMAS “JIM” ALEXANDER KEVIN E. BURKE STATE CONTRACTORS BOARD MARGARET CAVIN JOE HERNANDEZ NOTICE OF MEETING JAN B. LEGGETT STEPHEN P. QUINN * * * PUBLIC NOTICE * * * STATE CONTRACTORS BOARD MEETING DATE: JANUARY 22, 2015 TIME: 8:30 AM LOCATION: By Videoconference at the following locations: State Contractors Board Offices 2310 Corporate Circle, Suite 200 9670 Gateway Drive, Suite 100 Henderson, Nevada 89074 Reno, Nevada 89521 PLEASE NOTE: TO PROMOTE EFFICIENCY AND AS AN ACCOMMODATION TO THE PARTIES INVOLVED, AGENDA ITEMS MAY BE TAKEN OUT OF ORDER. NO CELL PHONES OR BEEPERS PLEASE! * * * AGENDA * * * 1. CALL TO ORDER: - GUY M. WELLS, Chairman a. Pledge of Allegiance b. Approval of Agenda with the Inclusion of any Emergency Items and Deletion of any Items – For Possible Action c. Unfinished Business d. Future Agendas – For Possible Action 2. ** PUBLIC COMMENT 3. APPROVAL OF MINUTES: November 13, 2014 – For Possible Action 4. EXECUTIVE SESSION – For Possible Action: a. Executive Officer’s Report b. Review and Approval of Quarterly Financial Reports for the Period Ending December 31, 2014 – For Possible Action c. Adoption as a Temporary Regulation of Proposed Amendments to NAC 624.170 Concerning Remodel of High Rise Buildings – For Possible Action d. Legislative Discussion – For Possible Action i. Assembly Bills 1, 43, 53, 60 72, 84, 89 Page 1 ii. Senate Bills 39, 50, 59, 83 e. Legal Report – For Possible Action f. Review and Approval of Executive Officer’s Quarterly Report and Strategic Plan Update for the Period Ending December 31, 2014 – For Possible Action g. -

The Role of Connexin Proteins and Their Channels in Radiation-Induced

Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences (2021) 78:3087–3103 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-020-03716-3 Cellular andMolecular Life Sciences REVIEW The role of connexin proteins and their channels in radiation‑induced atherosclerosis Raghda Ramadan1,2 · Sarah Baatout1,3 · An Aerts1 · Luc Leybaert2 Received: 16 July 2020 / Revised: 29 October 2020 / Accepted: 17 November 2020 / Published online: 3 January 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Radiotherapy is an efective treatment for breast cancer and other thoracic tumors. However, while high-energy radiotherapy treatment successfully kills cancer cells, radiation exposure of the heart and large arteries cannot always be avoided, resulting in secondary cardiovascular disease in cancer survivors. Radiation-induced changes in the cardiac vasculature may thereby lead to coronary artery atherosclerosis, which is a major cardiovascular complication nowadays in thoracic radiotherapy- treated patients. The underlying biological and molecular mechanisms of radiation-induced atherosclerosis are complex and still not fully understood, resulting in potentially improper radiation protection. Ionizing radiation (IR) exposure may damage the vascular endothelium by inducing DNA damage, oxidative stress, premature cellular senescence, cell death and infam- mation, which act to promote the atherosclerotic process. Intercellular communication mediated by connexin (Cx)-based gap junctions and hemichannels may modulate IR-induced responses and thereby the atherosclerotic process. However, the role of endothelial Cxs and their channels in atherosclerotic development after IR exposure is still poorly defned. A better understanding of the underlying biological pathways involved in secondary cardiovascular toxicity after radiotherapy would facilitate the development of efective strategies that prevent or mitigate these adverse efects. Here, we review the possible roles of intercellular Cx driven signaling and communication in radiation-induced atherosclerosis. -

A Constructional Perspective on the Rise of Metatextual Discourse Markers

cadernos.abralin.org RESEARCH REPORT A CONSTRUCTIONAL PERSPECTIVE ON THE RISE OF METATEXTUAL DISCOURSE MARKERS Elizabeth Closs TRAUGOTT Department of Linguistics - Stanford University ABSTRACT Cognitive linguistics seeks to account for “a speaker’s knowledge of the full range of linguistic conventions” (LANGACKER, 1987; also GOLD- BERG, 2006). It is surprising therefore that little attention has been paid in cognitive linguistics to the linguistic conventions called “discourse markers” (SCHIFFRIN, 1987) or “pragmatic markers” (FRASER, 2009, et passim). Pragmatic markers include signals of attention to social rela- tionships (well, please), beliefs (I think, in fact), and discourse manage- ment (after all, anyway). Members of the third subtype are metatextual connectors of discourse segments (“discourse markers” in Fraser’s tax- onomy). I argue that because pragmatic markers in general play a major OPEN ACCESS role in negotiating meaning, they are an important part of speakers’ EDITORS – Miguel Oliveira, Jr. (UFAL) knowledge of language. Pragmatic markers are well-known not to have – René Almeida (UFS) truth-conditional meaning, and not to be syntactically integrated with REVIEWERS the host clause. However, they have conventional pragmatic meanings – Mariângela Rios de Oliveira (UFF) (HANSEN, 2012; FINKBEINER, 2019). I exemplify my recent research on – Taísa Oliveira (UFMS) the historical development in English of metatextual discourse markers DATES with a diachronic construction grammar perspective on by the way – Received: 07/06/2020 – Accepted: 08/11/2020 (TRAUGOTT, 2020). Focus will be on the importance of routinized, repli- – Published: 01/14/2021 cated contexts in change (CROFT, 2001; BYBEE, 2010). HOW TO CITE TRAUGOTT, Elizabeth Closs (2021). A Constructional Perspective on The Rise of Metatextual Discourse Markers.