Stop and Search an Investigation of the Met's New Approach to Stop and Search February 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information to Police and Crime Committee's Review of Stop

Background information to Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search This document contains correspondence, written submissions, notes of meetings and site visits as part of the Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search Contents page 1. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 18 June 2013 1 2. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 8 August 2013 5 3. Letter from the Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime – 11 December 8 2013 4. Submission from the Independent Police Complaints Commission 11 5. Submission from Lisa Smallman 16 6. Submission from Raymond Swingler 17 7. Briefing paper and note of visit to Second Wave 18 8. Note of meeting with Christine Matthews, Chair of the pan-London stop 22 and search monitoring group TP - Capability and Support Joanne McCartney AM 17th Floor ESB North Chair of the Police and Crime Committee Empress State Building London Assembly Lillie Road City Hall London The Queen's Walk SW6 1TR London Telephone: 0207 161 0539 SE1 2AA Facsimile: Email: [email protected] www.met.police.uk Your ref: 11/2013 Our ref: 18 June 2013 Dear Ms McCartney, Thank you for my invitation to attend the Police and Crime Committee in July to discuss the MPS approach to stop and search. The MPS takes its responsibilities for the use of Stop & Search powers very seriously, recognising the important influence it has on the policing of London and the confidence of Londoners in the MPS. Since the Commissioner outlined his vision in February 2012 and the STOP IT programme was launched the MPS has made sound improvements in how stop and search is used. -

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to Those Founts of Pride and Joy

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to those founts of pride and joy Robert and Sarah Hodkinson of Holyport and Max Dennis of Pensacola Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Norman Dennis George Erdos Ahmed Al-Shahi Institute for the Study of Civil Society London First published September 2000 © The Institute for the Study of Civil Society 2000 email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 1-903 386-05 5 Typeset by the Institute for the Study of Civil Society in New Century Schoolbook Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Page The Authors viii Foreword David G. Green x Authors’ Note x Preface Norman Dennis xi Summary xix Introduction 1 Mrs Lawrence’s experience of racism The Macpherson report’s evidence and findings 1 The Main Issues 4 Stephen Lawrence’s death The murderers Racist criminality Police racism Remedies Passion and proportion 2 The Methods of Inquiry used by Macpherson 11 The Macpherson ‘court’ The abstraction of abject apologies The Taaffes Trial by pressure group 3 The Crowd in Hannibal House 20 The crowd and Mrs Lawrence The crowd and Inspector Groves The crowd and Detective Sergeant Bevan The crowd and Sir Paul Condon The gullible scepticism of special interest groups and those they succeed in influencing 4 Mr and Mrs Lawrence’s Treatment at the Hospital as Evidence of Police Racism 33 Acting Inspector Little’s alleged racism The Night Services Manager’s evidence 5 The Initial Treatment of Duwayne Brooks as Evidence of Police Racism 42 How he was -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways. -

The Macpherson Report: Twenty-Two Years On

House of Commons Home Affairs Committee The Macpherson Report: Twenty-two years on Third Report of Session 2021–22 Report, together with formal minutes relating to the report Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 21 July 2021 HC 139 Published on 30 July 2021 by authority of the House of Commons Home Affairs Committee The Home Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Home Office and its associated public bodies. Current membership Rt Hon Yvette Cooper MP (Labour, Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford) Chair Rt Hon Diane Abbott MP (Labour, Hackney North and Stoke Newington) Dehenna Davison MP (Conservative, Bishop Auckland) Ruth Edwards MP (Conservative, Rushcliffe) Laura Farris MP (Conservative, Newbury) Simon Fell MP (Conservative, Barrow and Furness) Andrew Gwynne MP (Labour, Denton and Reddish) Adam Holloway MP (Conservative, Gravesham) Dame Diana Johnson MP (Kingston upon Hull North) Tim Loughton MP (Conservative, East Worthing and Shoreham) Stuart C. McDonald MP (Scottish National Party, Cumbernauld, Kilsyth and Kirkintilloch East) The following Members were also Members of the Committee during this Parliament: Janet Daby MP (Labour, Lewisham East); Stephen Doughty MP (Labour (Co-op) Cardiff South and Penarth); Holly Lynch MP (Labour, Halifax) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021. This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament Licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/copyright. -

Counsel to the Inquiry's Opening Statement

UNDERCOVER POLICING INQUIRY ___________________________________________________________________ COUNSEL TO THE INQUIRY’S OPENING STATEMENT Contents Part 1 – Overview Part 2 – Tranche 1 Phase 1 Appendix 1 – Groups reported on by the SDS as set out in the Annual Reports 1969 to 1974s Appendix 2 – Phase 1 undercover officers and Phase 1 managers PART 1 – OVERVIEW Introduction 1. This Inquiry has been set up as a result of profound and wide-ranging concerns arising from the activities of two undercover police units. First, the Special Demonstration Squad (“the SDS”) which existed between 1968 and 2008. Second, the undercover element of the National Public Order Intelligence Unit (“the NPOIU”) which existed between 1999 and 2010. Our terms of reference are wide enough to encompass all undercover policing by English and Welsh police forces in England and Wales since 1968 but we shall be concentrating primarily upon the activities of these two units. 2. It has emerged that, for decades, undercover police officers infiltrated a significant number of political and other activist groups in deployments which typically lasted for years. The information reported by these undercover police officers was extensive. It covered the activities of the groups in question and their members. It also extended to the groups and individuals with whom they came into contact, including elected representatives. Reporting covered not only the political or campaigning activities of those concerned but other aspects of their personal lives. Groups mainly on the far left but also the far right of the political spectrum were infiltrated as well as groups campaigning for social, environmental or other change. -

Written Answers to Questions Not Answered at Mayor's Question Time on 17 July 2013 Confidence in the Met Pledge on Job Creation

Written Answers to Questions not answered at Mayor's Question Time on 17 July 2013 Confidence in the Met Question No: 2013/2433 Joanne McCartney Should Londoners have confidence in your oversight of the Metropolitan Police Service? Oral response Pledge on job creation Question No: 2013/2434 Fiona Twycross You pledged in your 2012 manifesto that you would create 200,000 jobs directly through City Hall programmes. Exactly how many of these jobs have you created so far? Oral response Your election manifesto and fire service cuts Question No: 2013/2435 Andrew Dismore Why did you not tell the people of London that you would support a proposal to close 12 of their fire stations, remove 18 of their fire engines, and cut 520 of their firefighters' jobs in your election manifesto last year? Oral response Fares Question No: 2013/2436 Valerie Shawcross Your manifesto said, 'My approach will ensure that fares will be lower in the long term', but since you have been Mayor, fares have gone up by 6%, 7.1%, 6.8%, 5.6% & 4.2%. Is this keeping your manifesto promise? Oral response NHS at 65 Question No: 2013/2437 Onkar Sahota On the 65th anniversary of the NHS, does the Mayor feel that London needs a pan-regional strategic health authority? Oral response Rough Sleeping Question No: 2013/2438 Tom Copley What will you do to stem the increase in rough sleeping? Oral response Air Pollution Question No: 2013/2439 Murad Qureshi Your 2012 manifesto pledged to 'champion improvement to London's air quality'. With your more substantive measures due to take place after the next mayoral election, are you delivering against this pledge? Oral response Affordable rent programme Question No: 2013/2251 Darren Johnson A publication on the GLA web site provides figures for Affordable Rent programme starts and completions for 2011-12 and 2012-13 for the whole of Greater London, and broken down by borough. -

< 1> Friday, 15Th May 1998. < 2>

< 1> Friday, 15th May 1998. < 2> THE CHAIRMAN: Good morning. Do sit down, thank you < 3> very much. Mr Lawson, before we start, there is just < 4> one announcement that I think I ought to make. < 5> Yesterday evening we had a meeting with all the lawyers < 6> involved and the represented parties in order to < 7> discuss the giving of evidence by the five young men < 8> who have been known as the suspects. There is no need < 9> for me to name them. <10> As a result of that discussion, it was indicated <11> to me that the lawyers on behalf of those five young <12> men propose to take proceedings by way of judicial <13> review in the divisional Court of the High Court in <14> order to test various matters in connection with the <15> summons that I issued and the vires, that is to say the <16> powers that were exercised in the making of the <17> original decision that this inquiry should be held. <18> I phrase the matter broadly because, of course, I <19> do not know exactly what the nature of the application <20> will be. I simply indicate that publicly. They <21> propose to make that application, but it will not hold <22> up the business of the Inquiry. We will, of course, <23> continue with our programme and call the witnesses as <24> they have been listed and as we hope that they will <25> appear between now and the time when they may come to . P-5054 < 1> give evidence. -

The Stephen Lawrence Inquiry

THE STEPHEN LAWRENCE INQUIRY REPORT OF AN INQUIRY BY SIR WILLIAM MACPHERSON OF CLUNY ADVISED BY TOM COOK, THE RIGHT REVEREND DR JOHN SENTAMU, DR RICHARD STONE Presented to Parliament by the Secretary of State for the Home Department by Command of Her Majesty. February 1999 Cm 4262-I Volume I CONTENTS Paragraph Prelim CHAPTER ONE The Murder of Stephen Lawrence CHAPTER TWO Since the Murder CHAPTER THREE The Inquiry Terms of Reference 3.1 Limited immunity 3.2 The Commissioner's intervention 20.4.98 3.16 The Advisers 3.24 Counsel and Solicitors 3.26 The Secretariat 3.29 CHAPTER FOUR Mr & Mrs Lawrence and Stephen CHAPTER FIVE Duwayne Brooks His evidence 5.5 At the scene 5.10 Stereotyped 5.12 At the hospital 5.13 At Plumstead Police Station 5.14 Liaison 5.17 His prosecution 5.27 Conclusion 5.30 CHAPTER SIX Racism Kent Report 6.2 Racism 6.4 Institutional racism 6.6 Unwitting racism 6.13 Failure of first investigation 6.21 The Commissioner's view 6.25 The MPS Black Police Association's view 6.27 1990 Trust 6.29 Commission for Racial Equality 6.30 Dr Robin Oakley 6.31 Dr Benjamin Bowling 6.33 The Inquiry's "definition" 6.34 Professor Simon Holdaway 6.37 Institutional racism present 6.45 ACPO view 6.49 Mr Paul Pugh 6.58 The Home Secretary 6.62 CHAPTER SEVEN The Five Suspects Research 7.11 Other offences 7.15 Witness K 7.25 Witness B 7.27 1994 Surveillance 7.31 Evidence at the Inquiry 7.39 Divisional Court ruling 7.40 Perjury 7.43 'Autrefois acquit' 7.46 CHAPTER EIGHT Corruption and Collusion The allegation 8.2 Standard of proof 8.5 The "Norris -

Fighting Crime - Locally

Fighting crime - locally Autumn LGA LIBERAL DEMOCRATS 2012 Photos on front page and page 6 : Third Avenue Contents 1. Introduction Page 5 Cllr Duwayne Brooks, Lead Member, Safer Communities Board, LGA Lib Dem Group 2. 10 Ways to Tackle Crime - Locally Page 6 3. Cutting Crime in Stockport Page 8 Cllr Mark Weldon, Stockport Metropolitan Borough Council 4. Islington Labour threatens Lib Dem Page 10 record of action on crime Cllr Terry Stacy, London Borough of Islington 5. Police Commissioners? Don’t panic! Page 15 Cllr Richard Kemp, Liverpool City Council 6. What’s life like with a directly elected Page 17 Police and Crime Commissioner? Caroline Pidgeon, Leader of the Liberal Democrat Group on the London Assembly 7. Newcastle - a proud Lib Dem record of action Page 19 Cllr Anita Lower, Newcastle City Council 8. The Somerset Story - Restorative Justice Page 23 Cllr Jill Shortland, Chair of the LGA Liberal Democrat Group 9. Community Justice - how it works in Sheffield Page 27 Cllr Shaffaq Mohammed, Sheffield City Council Fighting crime - locally 3 10. Working Together to help Vulnerable People Page 29 Cllr Lisa Brett, Bath and North East Somerset 11. Making a Difference in Portsmouth Page 32 Cllr Lynne Stagg, Portsmouth City Council 12. Police and Crime Panels - Page 35 Holding the Police Commissioners to Account Cllr Duwayne Brooks, London Borough of Lewisham Introduction With the elections of Police and Crime Commissioners in November, I felt it was timely to remind people of the contribution local councils and councillors can make to fighting crime and creating safer communities. Having led for the Liberal Democrats on the LGA Safer Communities Board, I felt it was important that the views of our councillors were heard very loudly. -

Spycops in Context: a Brief History of Political Policing in Britain Connor Woodman December 2018 About the Author

Spycops in context: A brief history of political policing in Britain Connor Woodman December 2018 About the author Connor Woodman is the 2017/18 Barry Amiel & Norman Melburn Trust Research Fellow, hosted by the Centre for Crime and Justice Studies. Acknowledgments I would like to thank the following people who read earlier drafts and offered useful comments: Koshka Duff, Donal O’Driscoll, Richard Garside and Richard Aldrich. Thank you to Helen Mills for her support and guidance through the entirety of the project, and to Tammy McGloughlin and Neala Hickey for their production work. Thanks also to the Hull History Centre and Jim Townsend for their assistance. The Research Fellowship was provided by the Barry Amiel & Norman Melburn Trust. The Trust aims to advance public education, learning and knowledge in all aspects of the philosophy of Marxism, the history of socialism, and the working-class movement: www.amielandmelburn.org.uk. Centre for Crime and Justice Studies 2 Langley Lane, Vauxhall, London SW8 1GB [email protected] www.crimeandjustice.org.uk © Centre for Crime and Justice Studies December 2018 ISBN: 978-1-906003-70-8 Registered charity No. 251588 A company limited by guarantee. Registered in England No. 496821 Cover photo: Striking miners being chased by mounted police at Orgreave, 18 June 1984 © Martin Jenkinson Image Library. All rights reserved. DACS/Artimage 2018 www.crimeandjustice.org.uk Contents Foreword ............................................................................ 1 Introduction ........................................................................ 2 Terminology, intelligence and state agencies ............................................... 3 Secrecy and sources ..................................................................................... 5 Before the SDS: political policing until the 1960s ............... 7 The early police: between the people and the army ..................................... -

UK Election Statistics: 1918- 2021: a Century of Elections

By Sam Pilling, RIchard Cracknell UK Election Statistics: 1918- 18 August 2021 2021: A Century of Elections 1 Introduction 2 General elections since 1918 3 House of Commons by-elections 4 European Parliament elections (UK) 5 Elections to devolved legislatures and London elections 6 Local Elections 7 Police and Crime Commissioner (PCC) Elections 8 Referendums 9 Appendix A: Voting systems and electoral geographies used in the UK elections commonslibrary.parliament.uk Number CBP7529 UK Election Statistics: 1918-2021: A Century of Elections Image Credits Autumn colours at Westminster by Manish Prabhune. Licensed by CC BY 2.0 / image cropped. Disclaimer The Commons Library does not intend the information in our research publications and briefings to address the specific circumstances of any particular individual. We have published it to support the work of MPs. You should not rely upon it as legal or professional advice, or as a substitute for it. We do not accept any liability whatsoever for any errors, omissions or misstatements contained herein. You should consult a suitably qualified professional if you require specific advice or information. Read our briefing ‘Legal help: where to go and how to pay’ for further information about sources of legal advice and help. This information is provided subject to the conditions of the Open Parliament Licence. Feedback Every effort is made to ensure that the information contained in these publicly available briefings is correct at the time of publication. Readers should be aware however that briefings are not necessarily updated to reflect subsequent changes. If you have any comments on our briefings please email [email protected]. -

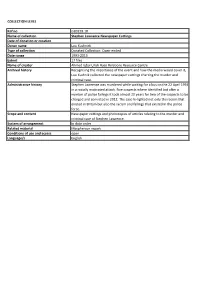

Collection Level

COLLECTION LEVEL Ref no GB3228.18 Name of collection Stephen Lawrence Newspaper Cuttings Date of donation or creation Donor name Lou Kushnick Type of collection Donated Collection: Open-ended Date range 1993-2013 Extent 17 files Name of creator Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Relations Resource Centre Archival history Recognising the importance of the event and how the media would cover it, Lou Kushnik collected the newspaper cuttings charting the murder and criminal case. Administrative history Stephen Lawrence was murdered while waiting for a bus on the 22 April 1993 in a racially motivated attack. Five suspects where identified but after a number of police failings it took almost 20 years for two of the suspects to be charged and convicted in 2012. The case hi-lighted not only the racism that existed in Britain but also the racism and failings that existed in the police force. Scope and content Newspaper cuttings and photocopies of articles relating to the murder and criminal case of Stephen Lawrence. System of arrangement In date order Related material Macpherson report Conditions of use and access open Language/s English SERIES LEVEL Ref no Name of series Date range Extent Name of creator Background toScope the series and content Detail ofRelated content material Conditions of use and access Language/s GB3228.18/1 Stephen Lawrence 2 May-22 Dec 1993 1 file Lou Kushnick n/a Press cuttings relating to n/a n/a open English Press Cuttings 1993 Stephen Lawrence case from 1993 GB3228.18/2 Stephen Lawrence 20 Jan-22 Sep 1995 1 file Lou Kushnick n/a