The Macpherson Report: Twenty-Two Years On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information to Police and Crime Committee's Review of Stop

Background information to Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search This document contains correspondence, written submissions, notes of meetings and site visits as part of the Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search Contents page 1. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 18 June 2013 1 2. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 8 August 2013 5 3. Letter from the Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime – 11 December 8 2013 4. Submission from the Independent Police Complaints Commission 11 5. Submission from Lisa Smallman 16 6. Submission from Raymond Swingler 17 7. Briefing paper and note of visit to Second Wave 18 8. Note of meeting with Christine Matthews, Chair of the pan-London stop 22 and search monitoring group TP - Capability and Support Joanne McCartney AM 17th Floor ESB North Chair of the Police and Crime Committee Empress State Building London Assembly Lillie Road City Hall London The Queen's Walk SW6 1TR London Telephone: 0207 161 0539 SE1 2AA Facsimile: Email: [email protected] www.met.police.uk Your ref: 11/2013 Our ref: 18 June 2013 Dear Ms McCartney, Thank you for my invitation to attend the Police and Crime Committee in July to discuss the MPS approach to stop and search. The MPS takes its responsibilities for the use of Stop & Search powers very seriously, recognising the important influence it has on the policing of London and the confidence of Londoners in the MPS. Since the Commissioner outlined his vision in February 2012 and the STOP IT programme was launched the MPS has made sound improvements in how stop and search is used. -

Review Report Launch Programme and Agenda

1 Introduction Covid-19 has highlighted health inequalities faced by Black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities and colleagues. The pandemic has also drawn attention to the impact of systemic racism on people’s lives. The West Yorkshire and Harrogate Health and Care Partnership (WY&H HCP) recognised the opportunity to address these issues, establishing a commission independently chaired by Professor Dame Donna Kinnair, Chief Executive and General Secretary of the Royal College of Nursing, a leading figure in national health and care policy. You can read more about Professor Dame Donna Kinnair on page 4. The review has been co-produced by leaders from the NHS, local government and the Voluntary and Community Sector (VCS); informed by the voices of those with lived experience. This session presents a one off opportunity to hear direct from review panel members and to find out more about the report recommendations, action plan and importantly the next steps for us all. It will be held digitally via Microsoft Teams. If you haven’t used Microsoft Teams before, this guidance explains how to join. All attendees are asked to please keep their microphones on mute whilst others are speaking. To join, please book your place on Eventbrite here by Wednesday 14 October 2020. 2 Today’s agenda 10.00am – 10.05am Hello and welcome. The importance of getting involved, my personal reflections as Chair and hopes for the future following the review Professor Dame Donna Kinnair (see Dame Donna’s biography on page 4) 10.05am – 10.10am Why it’s good -

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to Those Founts of Pride and Joy

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to those founts of pride and joy Robert and Sarah Hodkinson of Holyport and Max Dennis of Pensacola Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Norman Dennis George Erdos Ahmed Al-Shahi Institute for the Study of Civil Society London First published September 2000 © The Institute for the Study of Civil Society 2000 email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 1-903 386-05 5 Typeset by the Institute for the Study of Civil Society in New Century Schoolbook Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Page The Authors viii Foreword David G. Green x Authors’ Note x Preface Norman Dennis xi Summary xix Introduction 1 Mrs Lawrence’s experience of racism The Macpherson report’s evidence and findings 1 The Main Issues 4 Stephen Lawrence’s death The murderers Racist criminality Police racism Remedies Passion and proportion 2 The Methods of Inquiry used by Macpherson 11 The Macpherson ‘court’ The abstraction of abject apologies The Taaffes Trial by pressure group 3 The Crowd in Hannibal House 20 The crowd and Mrs Lawrence The crowd and Inspector Groves The crowd and Detective Sergeant Bevan The crowd and Sir Paul Condon The gullible scepticism of special interest groups and those they succeed in influencing 4 Mr and Mrs Lawrence’s Treatment at the Hospital as Evidence of Police Racism 33 Acting Inspector Little’s alleged racism The Night Services Manager’s evidence 5 The Initial Treatment of Duwayne Brooks as Evidence of Police Racism 42 How he was -

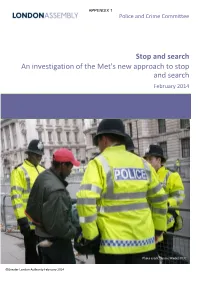

Stop and Search an Investigation of the Met's New Approach to Stop and Search February 2014

APPENDIX 1 Police and Crime Committee Stop and search An investigation of the Met's new approach to stop and search February 2014 Photo credit: Janine Wiedel/REX ©Greater London Authority February 2014 APPENDIX 1 Police and Crime Committee Members Joanne McCartney (Chair) Labour Jenny Jones (Deputy Chair) Green Caroline Pidgeon MBE (Deputy Chair) Liberal Democrat Tony Arbour Conservative Jennette Arnold OBE Labour John Biggs Labour Victoria Borwick Conservative Len Duvall Labour Roger Evans Conservative Contact: Claire Hamilton Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 5845 2 APPENDIX 1 Contents Foreword 4 Summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. Ensuring an accurate account of stop and search 14 3. Developing a culture of accountability 18 4. Ensuring rights are enforced 22 5. Developing a learning culture 26 6. Involving young people in change 31 7. Conclusion 35 8. Summary of recommendations 36 9. Appendices 38 Orders and translations 48 3 APPENDIX 1 Foreword As a long-time opponent of the Met’s extensive use of the stop and search tactic, I was delighted when the new Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, announced his intention to cut back on the number with his “StopIt” programme. This report seeks to assess the impact of that programme and suggests ways to improve things further still. Currently, over the course of a year, the Met carries out over 320,000 stop and searches. This means that every hour, at least 35 Londoners are stopped and searched. A further 375,000 people are asked to stop and account for their actions. We have asked whether this is a good use of the police’s time and energy. -

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 Diane ABBOTT MP

Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Labour Conservative Diane ABBOTT MP Adam AFRIYIE MP Hackney North and Stoke Windsor Newington Labour Conservative Debbie ABRAHAMS MP Imran AHMAD-KHAN Oldham East and MP Saddleworth Wakefield Conservative Conservative Nigel ADAMS MP Nickie AIKEN MP Selby and Ainsty Cities of London and Westminster Conservative Conservative Bim AFOLAMI MP Peter ALDOUS MP Hitchin and Harpenden Waveney A Labour Labour Rushanara ALI MP Mike AMESBURY MP Bethnal Green and Bow Weaver Vale Labour Conservative Tahir ALI MP Sir David AMESS MP Birmingham, Hall Green Southend West Conservative Labour Lucy ALLAN MP Fleur ANDERSON MP Telford Putney Labour Conservative Dr Rosena ALLIN-KHAN Lee ANDERSON MP MP Ashfield Tooting Members of the House of Commons December 2019 A Conservative Conservative Stuart ANDERSON MP Edward ARGAR MP Wolverhampton South Charnwood West Conservative Labour Stuart ANDREW MP Jonathan ASHWORTH Pudsey MP Leicester South Conservative Conservative Caroline ANSELL MP Sarah ATHERTON MP Eastbourne Wrexham Labour Conservative Tonia ANTONIAZZI MP Victoria ATKINS MP Gower Louth and Horncastle B Conservative Conservative Gareth BACON MP Siobhan BAILLIE MP Orpington Stroud Conservative Conservative Richard BACON MP Duncan BAKER MP South Norfolk North Norfolk Conservative Conservative Kemi BADENOCH MP Steve BAKER MP Saffron Walden Wycombe Conservative Conservative Shaun BAILEY MP Harriett BALDWIN MP West Bromwich West West Worcestershire Members of the House of Commons December 2019 B Conservative Conservative -

Regarding the Sale of Alcohol at 15 Branch Road Armley, I Am Writing to Object and Contest It Should Not Be Granted

From:Mudge, Peter Sent:25 May 2021 14:36:00 +0100 To:Deighton, Charlotte Subject:Amended Hi Charlotte, I realise one bit of my opposition to 15 Branch Rd is incorrect – where Alison Lowe mentions the 24 hr off licence has been closed. Here is a version with the erroneous bit removed. Can it still go without my phone number or email please. “Regarding the sale of alcohol at 15 Branch Road Armley, I am writing to object and contest it should not be granted. A general store concentrating on Lietuvaite - which I understand is a rye bread - would be most welcome, but the off-licence aspect would be exacerbation of Armley’s already nationally advertised drink problems. Crime & Disorder - The site is in one of the most problematic illegal drinking areas in Yorkshire and therefore the UK. Indeed in the national Phase 2 of the “UK Towns’ Fund”, the government is currently suggesting a combined project so they work with the public sector, businesses and community to find innovative solutions to problems faced in Armley town centre. Independent of this government involvement, asb in Armley escalated as current lockdowns eased. Consequently West Yorkshire Police and Leeds Anti-Social Behaviour team are undertaking a series of projects to combat crime and fear of crime. In a letter they distributed at the start of May to every business and household in the vicinity of Armley town centre their opening lines are: “Dear resident, business owner or proprietor, “We are aware of the history of high levels of anti-social behaviour in and around the Armley Town Street Area. -

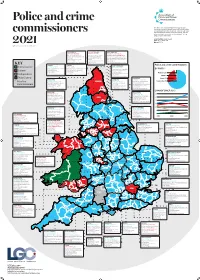

PCC Map 2021

Police and crime The APCC is the national body which supports police and crime commissioners and other local policing bodies across England and Wales to provide national leadership commissioners and drive strategic change across the policing, criminal justice and wider community safety landscape, to help keep our communities safe. [email protected] www.apccs.police.uk 2021 @assocPCCs © Local Government Chronicle 2021 NORTHUMBRIA SOUTH YORKSHIRE WEST YORKSHIRE KIM MCGUINNESS (LAB) ALAN BILLINGS (LAB) MAYOR TRACY BRABIN (LAB) First elected 2019 by-election. First elected 2014 by-election. Ms Brabin has nominated Alison Lowe Former cabinet member, Newcastle Former Anglican priest and (Lab) as deputy mayor for policing. Former City Council. deputy leader, Sheffield City councillor, Leeds City Council and chair of www.northumbria-pcc.gov.uk Council. West Yorkshire Police and Crime Panel. 0191 221 9800 www.southyorkshire-pcc.gov.uk 0113 348 1740 [email protected] 0114 296 4150 [email protected] KEY [email protected] CUMBRIA DURHAM Police and crime commissioners NORTH YORKSHIRE PETER MCCALL (CON) JOY ALLEN (LAB) Conservative PHILIP ALLOTT (CON)* First elected 2016. Former colonel, Former Durham CC cabinet member and Former councillor, Harrogate BC; BY PARTY Royal Logistic Corps. former police and crime panel chair. former managing director of Labour www.cumbria-pcc.gov.uk www.durham-pcc.gov.uk marketing company. 01768 217734 01913 752001 Plaid Cymru 1 www.northyorkshire-pfcc.gov.uk Independent [email protected] [email protected] 01423 569562 Vacant 1 [email protected] Plaid Cymru HUMBERSIDE Labour 11 LANCASHIRE CLEVELAND JONATHAN EVISON (CON) * Also fi re ANDREW SNOWDEN (CON) NORTHUMBRIA STEVE TURNER (CON) Councillor at North Lincolnshire Conservative 29 Former lead member for highways Former councillor, Redcar & Council and former chair, Humberside Police and Crime Panel. -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways. -

London Manchester Number of Employees by Parliamentary

Constituency MP Employees Constituency MP Employees Aberavon Stephen Kinnock 8 Jacobs UK Ltd 1 TWI Ltd 8 KAEFER Limited 18 Aberconwy Robin Millar 4 KDC Contractors Ltd 7 Dounreay Matom Limited 4 Kier Infrastructure and Overseas Ltd Thurso, Caithness 50 Aberdeen North Kirsty Blackman 6 Matom Limited gov.uk/government/organisations/dounreay 9 Bury North Salford SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 1 Mott MacDonald Ltd 2 SLC: Dounreay Site Restoration Ltd Manchester & Eccles Thornton Tomasetti 5 URENCO 485 PBO: Cavendish Dounreay Partnership Ltd Worsley & Aberdeen South Stephen Flynn 2 URENCO Nuclear Stewardship 84 (Cavendish Nuclear, Jacobs, Amentum) Eccles South AECOM 2 Coatbridge, Chryston & Bellshill Steven Bonnar 71 Lifetime: 1955–1994 Airdrie & Shotts Neil Gray 70 Jacobs UK Ltd 43 Operation: Development of prototype fast Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 22 Scottish Enterprise 1 breeder reactors Bolton West BRC Reinforcement Ltd 41 SNC-Lavalin/Atkins 27 People: More than 600 ENGIE UK 3 Copeland Trudy Harrison 13,314 Caithness, Sutherland & Easter Ross Wigan Morgan Sindall Infrastructure 4 AECOM 11 Aldershot Leo Docherty 62 ARUP 46 Fluor Corporation 12 Assystem UK Ltd 27 Mirion Technologies (IST) Limited 49 Balfour Beatty Kilpatrick 151 NuScale Power 1 Bechtel 2 Manchester Aldridge-Brownhills Wendy Norton 19 Bureau Veritas UK Ltd 71 The UK Civil Nuclear Industry Central Stainless Metalcraft (Chatteris) Ltd 19 Capita Group 382 Altrincham & Sale West Sir Graham Brady 92 Capula Ltd 10 Mott MacDonald Ltd 92 Cavendish Nuclear Ltd 207 Denton Alyn & Deeside Rt Hon -

Sangh Mail Nov 2020 Edition 1-0

NOV 2020 EDITION Sangh Mail is an internal organizational publication and for well-wishers to keep them informed on recent updates and news on a monthly basis. It is not for public distribution. Please continue to send in your news and views related to your shakhas / Swayamsevaks/ Sevikas/ for wider sharing and inspiration at [email protected] 46-48 Loughborough Road, Leicester, LE4 5LD II [email protected] II Registered Charity No. 267309 II www.hssuk.org NOV 2020 EDITION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Contact us: [email protected] 2 NOV 2020 EDITION UK PARLIAMENT WEEK AT BARNET SHAKTI AND PRATAP SHAKHA Throw back to 2017 and Pratap Sangh and Shakti Shakha are trailblazers for UK Parliament Week – B being the first to participate in UKPW by any Hindu Organisation in the UK. Fast forward to 2020 Barnet and 40+ Shakhas are now holding UK Parliament Week from Scotland to Surrey, Wales to Essex. We’ve made history! Barnet Parliament Week, buzzed with debate on ‘ Schools should remain open during the pandemic’ We highlighted our SEWA activities locally with ‘Donate a Food Bag’ campaign. Hindus should be more active in politics is the message from MP Matthew Offord, Theresa Villiers and councillor Roberto Weeden-Sanz. The entire event was steered by under 25yr old Swayamsevaks and Sevikas BIRMINGHAM SEVIKAS CELEBRATE PARLIAMENT WEEK - Draupadi, Vidula and Laxmi Samiti Birmingham celebrated UKPW for the first time on Friday, 6th November with a sankhya of 30. The B event took place online on zoom. We had 3 speakers who put across their issues forward. Nandini - Birmingham University journey through Covid, Vaibhavi - Hinduism should be taught in RE and Aayushi - How the government and people should spread environmental awareness in the society. -

Annual Learning Event 2017 – from Short Changed to System Change: Participants Thursday 27 April 2017 – St George’S Centre, Leeds

Annual Learning Event 2017 – From short changed to system change: participants Thursday 27 April 2017 – St George’s Centre, Leeds Name Job Title Organisation Roger Abbott Workforce Development & Learning Co- DISC WY-FI Project ordinator Joe Alderdice WY-FI Development & Engagement Lead DISC WY-FI Project Shaun Allison WY-FI Engagement & Co-Production Worker DISC WY-FI Project Hannah Anderson Deputy Head of Practice Collaborate Deby Atkinson No Second Night Out Project Leader Harrogate Homeless Project Danielle Barnes WY-FI Engagement & Co-Production Worker DISC WY-FI Project Alison Barrie DIP/IOM Project Manager DISC Jocelyn Bass Development Manager Leeds Housing Concern Angela Berthebaud Trainee Navigator WY-FI - Bridge Jim Black Chair DISC Sharon Booth Administrator WY-FI Graham Bowpitt Reader in Social Policy Nottingham Trent University Sharon Brown Development Manager Leeds Housing Concern Julie Burnham wrds service manager wrds Carla Carr Recovery Champion Forward Leeds Rebecca Carrington Lead Practitioner DISC Chelsea Cavanagh Student Placement Forum Central Nicola Chapman Key Worker Together Women Project Fidelis Chebe BME Engagement WY-FI Project Eleanor Clark Commissioning Support Officer Leeds City Council Jackie Codman Partnership Support Manager Department for Work and Pensions Dewsbury Duncan Connor Navigator Foundation (WY-FI) Andrew Corley Senior Research Excutive CFE Gill Crawshaw Development worker Forum Central Richard Crisp Senior Research Fellow CRESR at SHU Mark Crowe Research DISC Scott Cunningham Independent Facilitator -

Open PDF 326KB

Home Affairs Committee Oral evidence: Home Office preparedness for Covid- 19, HC 232 Wednesday 3 February 2021 Ordered by the House of Commons to be published on 3 February 2021. Watch the meeting Members present: Yvette Cooper (Chair); Dehenna Davison; Laura Farris; Andrew Gwynne; Adam Holloway; Tim Loughton; Stuart C. McDonald. Questions 913-970 Witnesses I: Nicole Jacobs, designate Domestic Abuse Commissioner for England and Wales, Lucy Hadley, Head of Policy & Campaigns, Women’s Aid, and Rosie Lewis, Deputy Director & Violence against Women and Girls (VAWG) Services Manager, the Angelou Centre. II: Lorna Gledhill, Deputy Director, Asylum Matters, Dr Jill O’Leary, GP Medical Advisory Service, Helen Bamber Foundation, and Theresa Schleicher, Casework Manager, Medical Justice. Written evidence from witnesses: COR0200 designate Domestic Abuse Commissioner for England and Wales COR0202 Women’s Aid COR0205 Medical Justice COR0206 Helen Bamber Foundation and other organisations Examination of witnesses Witnesses: Nicole Jacobs, Lucy Hadley and Rosie Lewis. Chair: Welcome to this evidence session for the Home Affairs Select Committee as part of our ongoing work scrutinising the work of the Home Office during the coronavirus crisis. Our first panel this morning will look at what is happening on domestic abuse during the covid crisis. I am very grateful to have the time of our witnesses here this morning. I welcome Nicole Jacobs, the designate Domestic Abuse Commissioner for England and Wales, Lucy Hadley, the head of policy and campaigns at Women’s Aid, and Rosie Lewis, the deputy director and violence against women and girls services manager at the Angelou Centre. We are very grateful for your time this morning.