Curing Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Background Information to Police and Crime Committee's Review of Stop

Background information to Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search This document contains correspondence, written submissions, notes of meetings and site visits as part of the Police and Crime Committee’s review of stop and search Contents page 1. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 18 June 2013 1 2. Letter from Supt Andy Morgan – 8 August 2013 5 3. Letter from the Deputy Mayor for Policing and Crime – 11 December 8 2013 4. Submission from the Independent Police Complaints Commission 11 5. Submission from Lisa Smallman 16 6. Submission from Raymond Swingler 17 7. Briefing paper and note of visit to Second Wave 18 8. Note of meeting with Christine Matthews, Chair of the pan-London stop 22 and search monitoring group TP - Capability and Support Joanne McCartney AM 17th Floor ESB North Chair of the Police and Crime Committee Empress State Building London Assembly Lillie Road City Hall London The Queen's Walk SW6 1TR London Telephone: 0207 161 0539 SE1 2AA Facsimile: Email: [email protected] www.met.police.uk Your ref: 11/2013 Our ref: 18 June 2013 Dear Ms McCartney, Thank you for my invitation to attend the Police and Crime Committee in July to discuss the MPS approach to stop and search. The MPS takes its responsibilities for the use of Stop & Search powers very seriously, recognising the important influence it has on the policing of London and the confidence of Londoners in the MPS. Since the Commissioner outlined his vision in February 2012 and the STOP IT programme was launched the MPS has made sound improvements in how stop and search is used. -

The Need for a Rights-Based Public Health Approach to Australian Asylum Seeker Health Jo Durham1* , Claire E

Durham et al. Public Health Reviews (2016) 37:6 DOI 10.1186/s40985-016-0020-9 REVIEW Open Access The need for a rights-based public health approach to Australian asylum seeker health Jo Durham1* , Claire E. Brolan1,2, Chi-Wai Lui1 and Maxine Whittaker1,3 * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract 1Faculty of Medicine & Biomedical Sciences, School of Public Health Public health professionals have a responsibility to protect and promote the right to School of Public Health, The health amongst populations, especially vulnerable and disenfranchised groups, such University of Queensland, Herston as people seeking asylum and whose health care is frequently compromised. As at Road, Herston, Queensland 4006, Australia 31 March 2016, there was a total of 3707 people (including 384 children) in immigration Full list of author information is detention facilities or community detention in Australia, with 431 of them detained for available at the end of the article more than 2 years. The Public Health Association of Australia and the Australian Medical Association assert that people seeking asylum in Australia have a right to health in the same way as Australian citizens, and they denounce detention of such people in government facilities for prolonged and indeterminate periods of time. The position of these two professional organisations is consistent with the compelling body of evidence demonstrating the negative impact detention has on health. Yet in recent years, both the Labour and Liberal parties—when at the helm of Australia’s Federal Government—have implemented a suite of regressive policies toward individuals seeking asylum. This has involved enforced legal restrictions on dissenting voices of those working with these populations, including health professionals. -

Extract from Book 17)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY FIFTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION Thursday, 8 December 2016 (Extract from book 17) Internet: www.parliament.vic.gov.au/downloadhansard By authority of the Victorian Government Printer Following a select committee investigation, Victorian Hansard was conceived when the following amended motion was passed by the Legislative Assembly on 23 June 1865: That in the opinion of this house, provision should be made to secure a more accurate report of the debates in Parliament, in the form of Hansard. The sessional volume for the first sitting period of the Fifth Parliament, from 12 February to 10 April 1866, contains the following preface dated 11 April: As a preface to the first volume of “Parliamentary Debates” (new series), it is not inappropriate to state that prior to the Fifth Parliament of Victoria the newspapers of the day virtually supplied the only records of the debates of the Legislature. With the commencement of the Fifth Parliament, however, an independent report was furnished by a special staff of reporters, and issued in weekly parts. This volume contains the complete reports of the proceedings of both Houses during the past session. In 2016 the Hansard Unit of the Department of Parliamentary Services continues the work begun 150 years ago of providing an accurate and complete report of the proceedings of both houses of the Victorian Parliament. The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AM The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable Justice MARILYN WARREN, AC, QC The ministry (to 9 November 2016) Premier ........................................................ The Hon. D. M. Andrews, MP Deputy Premier and Minister for Education, and Minister for Emergency Services (from 10 June 2016) [Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation 10 June to 20 June 2016] .................. -

Hyperreal Australia the Construction of Australia in Neighbours and Home & Away

Hyperreal Australia the construction of Australia in Neighbours and Home & Away Melissa McEwen March 2001 This volume is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts of the Australian National University in the Department of Australian Studies I wish to confirm that the thesis is my own work and that all sources used have been acknowledged. Melissa McEwen 30 March 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS Statement of authorship ii Table of contents iii Acknowledgments iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Neighbours 5 Employment 7 Education 10 E thnicity 12 W om en 14 Masculinity 18 Relationships and sexuality 20 Lifestyle 22 Disease and mental illness 25 C onclusion 26 3. Home & Away 27 Employment 30 Education 32 Ethnicity 34 W om en 37 Masculinity 42 Relationships and sexuality 45 Lifestyle 48 Disease and mental illness 49 Conclusion 51 4. National Stories 52 What is soap opera? 52 National myths and representation 56 Jobs and education 60 Ethnicity and racism 64 W om en 67 Masculinity 72 Relationships and sexuality 75 Lifestyles 77 Disease and mental illness 79 C onclusion 80 iii j. Constructing Australia 81 Construction and reception of soaps 81 Impact of television 88 Hyperreal Australia 92 Conclusion 107 i. A Moment’s Reflection 108 Mbliography 111 iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As this thesis has been a long time in gestation, there are a number of people to thanks for their assistance and help: Jon McConachie for starting me down this path and John Docker for guiding me to the end; Ann Curthoys and Noel Purdon for helping to ensure -

National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 18/19

National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 18/19 Study of Louis Nowra 2018 by Imants Tillers commissioned with funds provided by Tim Bednall, Jillian Broadbent ao, John Kaldor ao and Naomi Milgrom ao, Anna Meares 2018 by Narelle Autio commissioned with funds provided by King & Wood Mallesons and Li Cunxin 2017–18 by Jun Chen commissioned with funds provided by Tim Fairfax ac. On display as part of the 20/20: Celebrating twenty years with twenty new portrait commissions exhibition. b National Portrait Gallery of Australia Annual Report 18/19 © National Portrait Gallery The National Portrait Gallery is located on of Australia 2019 King Edward Terrace in the Parliamentary Zone of Canberra. issn 2204-0811 Location and opening hours All rights reserved. No part of this publication The National Portrait Gallery is situated in front may be reproduced or transmitted in any form of the High Court and alongside the National or by any means, electronic or mechanical Gallery of Australia. The Gallery is open daily (including photocopying, recording or any from 10.00am to 5.00pm, except for Christmas information storage and retrieval system), Day 25, December. For more information visit without permission from the publisher. portrait.gov.au All photographs unless otherwise stated Parking by Mark Mohell. The underground public car park can be accessed from Parkes Place. The car park is open seven This report is also accessible on the days per week and closes at 5.30pm. Parking National Portrait Gallery’s website spaces for people with mobility difficulties are portrait.gov.au provided in the car park close to the public access lifts. -

Meeting Report Brussels, Belgium : 19-20 June 2006

1 Violence Prevention Alliance Participant Meeting: Meeting Report Brussels, Belgium : 19-20 June 2006 Introduction The Violence Prevention Alliance (VPA) is a network of WHO Member State governments, nongovernmental and community-based organizations, and private, international and intergovernmental agencies working to prevent violence. VPA activities aim to facilitate the development of policies, programmes and tools to implement the recommendations of the World report on violence and health in communities, countries, and regions around the world, and attempt to strengthen sustained, multi-sectoral cooperation around this shared vision for violence prevention. This was the first meeting for the VPA where the content was dedicated exclusively to Alliance topics. Its purpose was to convene VPA participants in order to brainstorm and plan for the future strategic direction of the VPA. The meeting objectives were to: Get to know participants better Develop a strategy to increase VPA impact Plan upcoming VPA activities Discuss the resources and commitment for concrete action Review of m eeting discussions Day One The meeting was opened by Monsieur Christiaan Decoster, Director-General of FPS Health, Belgium Ministry of Health. Dr Etienne Krug followed with a brief description of the VPA. Dr Alex Butchart presented the meeting aims and provided a overview of VPA aims, objectives, working methods, and achievements to date. The remainder of the morning session was dedicated to VPA participant introductions where participants detailed what their respective agency does, why they are interested in participating in the VPA, and what they believe they can contribute to the Alliance. The afternoon session started with an overview of the VPA survey findings. -

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to Those Founts of Pride and Joy

Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Dedicated to those founts of pride and joy Robert and Sarah Hodkinson of Holyport and Max Dennis of Pensacola Racist Murder and Pressure Group Politics Norman Dennis George Erdos Ahmed Al-Shahi Institute for the Study of Civil Society London First published September 2000 © The Institute for the Study of Civil Society 2000 email: [email protected] All rights reserved ISBN 1-903 386-05 5 Typeset by the Institute for the Study of Civil Society in New Century Schoolbook Printed in Great Britain by The Cromwell Press Trowbridge, Wiltshire Contents Page The Authors viii Foreword David G. Green x Authors’ Note x Preface Norman Dennis xi Summary xix Introduction 1 Mrs Lawrence’s experience of racism The Macpherson report’s evidence and findings 1 The Main Issues 4 Stephen Lawrence’s death The murderers Racist criminality Police racism Remedies Passion and proportion 2 The Methods of Inquiry used by Macpherson 11 The Macpherson ‘court’ The abstraction of abject apologies The Taaffes Trial by pressure group 3 The Crowd in Hannibal House 20 The crowd and Mrs Lawrence The crowd and Inspector Groves The crowd and Detective Sergeant Bevan The crowd and Sir Paul Condon The gullible scepticism of special interest groups and those they succeed in influencing 4 Mr and Mrs Lawrence’s Treatment at the Hospital as Evidence of Police Racism 33 Acting Inspector Little’s alleged racism The Night Services Manager’s evidence 5 The Initial Treatment of Duwayne Brooks as Evidence of Police Racism 42 How he was -

The Surgeon Solving Violent Crime with Data Sharing

FEATURE The BMJ VIOLENCE PREVENTION [email protected] Cite this as: BMJ 2020;371:m2987 http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m2987 The surgeon solving violent crime with data sharing Sharing data to prevent violence is a revelation that came to Jonathan Shepherd 30 years ago—and is now significantly cutting violent injuries worldwide, writes Shivali Fulchand Shivali Fulchand It was a busy morning in 1982 in the operating theatre local government, frontline hospital staff, and the at Pinderfields Hospital, Wakefield. Jonathan police to discuss the idea. Initially, the police were Shepherd, a specialist surgical trainee in Leeds, was sceptical: they didn’t think that so much crime could attending to a surgical list involving head and neck be missed. But a snapshot police audit prompted by injuries. “There are always more assaults during the that first meeting showed that three quarters of miners’ strikes,” his colleague said. The conversation violent crime recorded by emergency departments moved on, but the comment stuck with Shepherd: was unknown to police in the city. The police were are there really more assaults during a strike, he convinced enough to at least try some of Shepherd’s wondered? ideas, and the Cardiff model was born. Violence is the cause of 1.4 million deaths a year and The Cardiff model is considered a global health issue by the World The model involves continuous collection of Health Organization.1 Although homicide causes less particular information by reception staff when a than 1% of deaths, it can be as high as 10% and, in patient checks into a hospital emergency department, some countries, is the leading cause of death in 15-49 including where the violence took place, the weapon year olds.2 Hospitals in England and Wales recorded used, the date and time of the attack, and the number 190 747 emergency department attendances related of assailants. -

Stop and Search an Investigation of the Met's New Approach to Stop and Search February 2014

APPENDIX 1 Police and Crime Committee Stop and search An investigation of the Met's new approach to stop and search February 2014 Photo credit: Janine Wiedel/REX ©Greater London Authority February 2014 APPENDIX 1 Police and Crime Committee Members Joanne McCartney (Chair) Labour Jenny Jones (Deputy Chair) Green Caroline Pidgeon MBE (Deputy Chair) Liberal Democrat Tony Arbour Conservative Jennette Arnold OBE Labour John Biggs Labour Victoria Borwick Conservative Len Duvall Labour Roger Evans Conservative Contact: Claire Hamilton Email: [email protected] Tel: 020 7983 5845 2 APPENDIX 1 Contents Foreword 4 Summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. Ensuring an accurate account of stop and search 14 3. Developing a culture of accountability 18 4. Ensuring rights are enforced 22 5. Developing a learning culture 26 6. Involving young people in change 31 7. Conclusion 35 8. Summary of recommendations 36 9. Appendices 38 Orders and translations 48 3 APPENDIX 1 Foreword As a long-time opponent of the Met’s extensive use of the stop and search tactic, I was delighted when the new Commissioner, Sir Bernard Hogan-Howe, announced his intention to cut back on the number with his “StopIt” programme. This report seeks to assess the impact of that programme and suggests ways to improve things further still. Currently, over the course of a year, the Met carries out over 320,000 stop and searches. This means that every hour, at least 35 Londoners are stopped and searched. A further 375,000 people are asked to stop and account for their actions. We have asked whether this is a good use of the police’s time and energy. -

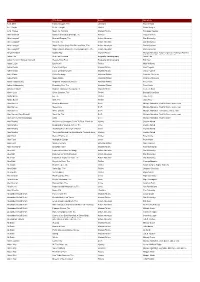

List of All the Audiobooks That Are Multiuse (Pdf 608Kb)

Authors Title Name Genre Narrators A. D. Miller Faithful Couple, The Literature Patrick Tolan A. L. Gaylin If I Die Tonight Thriller Sarah Borges A. M. Homes Music for Torching Modern Fiction Penelope Rawlins Abbi Waxman Garden of Small Beginnings, The Humour Imogen Comrie Abie Longstaff Emerald Dragon, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Firebird, The Action Adventure Dan Bottomley Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Blizzard Bear, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abie Longstaff Magic Potions Shop: The Young Apprentice, The Action Adventure Daniel Coonan Abigail Tarttelin Golden Boy Modern Fiction Multiple Narrators, Toby Longworth, Penelope Rawlins, Antonia Beamish, Oliver J. Hembrough Adam Hills Best Foot Forward Biography Autobiography Adam Hills Adam Horovitz, Michael Diamond Beastie Boys Book Biography Autobiography Full Cast Adam LeBor District VIII Thriller Malk Williams Adèle Geras Cover Your Eyes Modern Fiction Alex Tregear Adèle Geras Love, Or Nearest Offer Modern Fiction Jenny Funnell Adele Parks If You Go Away Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adele Parks Spare Brides Historical Fiction Charlotte Strevens Adrian Goldsworthy Brigantia: Vindolanda, Book 3 Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adrian Goldsworthy Encircling Sea, The Historical Fiction Peter Noble Adriana Trigiani Supreme Macaroni Company, The Modern Fiction Laurel Lefkow Aileen Izett Silent Stranger, The Thriller Bethan Dixon-Bate Alafair Burke Ex, The Thriller Jane Perry Alafair Burke Wife, The Thriller Jane Perry Alan Barnes Death in Blackpool Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes Nevermore Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. cast Alan Barnes White Ghosts Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Tom Baker, and a. cast Alan Barnes, Gary Russell Next Life, The Sci Fi Multiple Narrators, Paul McGann, and a. -

English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions About Black People in England

Trish Bater 080207052 ‘Blacking Up’: English Folk Traditions and Changing Perceptions about Black People in England Submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy by Patricia Bater National Centre for English Cultural Tradition March 2013 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. Trish Bater 080207052 2 Abstract This thesis investigates the custom of white people blacking their faces and its continuation at a time when society is increasingly aware of accusations of racism. To provide a context, an overview of the long history of black people in England is offered, and issues about black stereotypes, including how ‘blackness’ has been perceived and represented, are considered. The historical use of blackface in England in various situations, including entertainment, social disorder, and tradition, is described in some detail. It is found that nowadays the practice has largely been rejected, but continues in folk activities, notably in some dance styles and in the performance of traditional (folk) drama. Research conducted through participant observation, interview, case study, and examination of web-based resources, drawing on my long familiarity with the folk world, found that participants overwhelmingly believe that blackface is a part of the tradition they are following and is connected to its past use as a disguise. However, although all are aware of the sensitivity of the subject, some performers are fiercely defensive of blackface, while others now question its application and amend their ‘disguise’ in different ways. -

Using A&E Data for Crime Reduction

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. Injury surveillance: using A&E data for crime reduction Technical report Chris Giacomantonio, Alex Sutherland, Adrian Boyle, Jonathan Shepherd, Kristy Kruithof and Matthew Davies Injury surveillance: Using A&E data for crime reduction – Technical report College of Policing Limited Leamington Road Ryton-on-Dunsmore Coventry, CV8 3EN Publication date: December 2014 © – College of Policing Limited (2014) You may copy, republish, distribute, transmit and combine information featured in this publication (excluding logos) with other information, free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Non-Commercial College Licence v1.1.