How to Avoid a Climate Disaster : the Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need / Bill Gates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

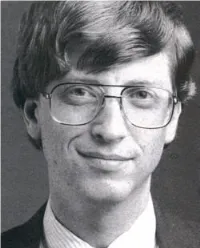

Bill Gates.Pdf

Bill Gates 1 Bill Gates Bill Gates Bill Gates au Medef en janvier 2008. Naissance 28 octobre 1955 Seattle, État de Washington États-Unis Profession(s) ex-PDG de Microsoft Directeur depuis juin 2008 Famille Jennifer Katharine Gates (1996) Rory John Gates (1999) Phoebe Adele Gates (2002) Signature William Henry Gates III dit Bill Gates est un informaticien américain né le 28 octobre 1955 à Seattle, pionnier dans le domaine de la micro informatique. Il a fondé en 1975, à l'âge de 20 ans, avec son ami Paul Allen, la société de logiciels de micro-informatique Micro-Soft (renommée depuis Microsoft). Son entreprise a acheté le système d'exploitation QDOS pour en faire MS-DOS, puis a conçu Windows, tous deux en situation de quasi-monopole mondial. Il est devenu, grâce au succès commercial de Microsoft, l'homme le plus riche du monde de 1996 à 2007 et en 2009. En mars 2010 sa fortune personnelle est estimée à 53 milliards de dollars[1] . Il est également Chevalier de l'Empire Britannique. Bill Gates a quitté Microsoft le 27 juin 2008 pour se consacrer à sa fondation humanitaire. Bill Gates 2 Les années de formation : 1955-1975 Bill Gates naît le 28 octobre 1955 à Seattle, État de Washington, aux États-Unis. Son père, William Henry Gates Sr., est avocat d'affaires. Sa mère, Mary Maxwell Gates, est professeur et présidente de la direction de quelques entreprises et banques de la United Way of America. Bill Gates découvre l'informatique à la très sélective Lakeside School de Seattle, qui dispose alors d'un PDP-10 loué. -

Chapter 3: Good News, Mixed Blessings

Chapter 3 Chapter 3 Good News and Mixed Blessings There are two futures, the future of desire and the future of fate, and man s reason has never learnt to separate them. - J. D. Bernal (1929)1 We are entering a new stage of the Internet: high-capacity (includ- ing video) communications will become available and affordable on a global scale. The upgraded Internet will change the world s one- way flow of mass communications to passive audiences and permit a more democratic and participatory future. Earlier, direct communi- cation with many people on a global scale was prohibitively expen- sive. Next, these technical and economic barriers will be mitigated. Ordinary individuals and institutions can create and send text and sound, and even television, from desktop PCs to global destinations; select their channels and linkups from thousands (or even millions) of options from around the world; and interact with other users. What w ill be the social and political impact of these new capabili- ties? - A first, broad, answer is that there is good news ahead. Com- munications is a part of almost every human activity: Technologies 1 Quoted in: Arthur C. Clarke, "Review: Imagined Worlds by Freeman Dyson (1997)," in Greetings Carbon-Based Bipeds: Collected Essays 1934 - 1998, ed. Athur C. Clarke (New York: St. Martin's Griffin, 1999), 497. June 14, 2002 1 Chapter 3 that support it will be faster, cheaper, more powerful - all, by several orders of magnitude - and capable of a global range. Everybody (individuals and organizations) w ill benefit. - The second broad answ er - to w hich part II of this book is devoted - is that, to a greater degree than before in history, the future will not be determined by impersonal forces carrying us to a prewired destination. -

MAT TYPE 001 L578o "Levine, Lawrence W"

CALL #(BIBLIO) AUTHOR TITLE LOCATION UPDATED(ITEM) MAT TYPE 001 L578o "Levine, Lawrence W" "The opening of the American mind : canons, culture, and history / Lawrence W. Levine" b 001.56 B632 "The Body as a medium of expression : essays based on a course of lectures given at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London / edited by Jonathan Benthall and Ted Polhemus" b 001.9 Sh26e "Shaw, Eva, 1947-" "Eve of destruction : prophecies, theories, and preparations for the end of the world / by Eva Shaw" b 001.942 C841u "Craig, Roy, 1924-" UFOs : an insider's view of the official quest for evidence / by Roy Craig b 001.942 R159p "Randle, Kevin D., 1949-" Project Blue Book exposed / Kevin D. Randle b 001.942 St97u "Sturrock, Peter A. (Peter Andrew)" The UFO enigma : a new review of the physical evidence / Peter A. Sturrock b 001.942 Uf7 The UFO phenomenon / by the editors of Time- Life Books b 001.944 M191m "Mackal, Roy P" The monsters of Loch Ness / Roy P. Mackal b 001.944 M541s "Meredith, Dennis L" Search at Loch Ness : the expedition of the New York times and the Academy of Applied Science / Dennis L. Meredith b 001.96 L891s "Lorie, Peter" Superstitions / Peter Lorie b 004 P587c "Pickover, Clifford A" Computers and the imagination : visual adventures beyond the edge / Clifford A. Pickover b 004.16 R227 2001 Reader's Digest the new beginner's guide to home computing b 004.1675 Ip1b3 2013 "Baig, Edward C" iPad for dummies / by Edward C. Baig and Bob Dr. Mac LeVitus b 004.1675 Ip2i 2012 "iPhone for seniors : quickly start working with the user-friendly -

Portable Paper

Vol. 5, No. 2 The HP Portable/Portable Plus/Portable Vectra Users Newsletter March / April 1990 PortableTHE Paper ~:~~Yil .','" i,; ;>".~ __ o -''''-11 :'i,"::"~: r.); ~~i/.~! ~~i tl r?::~~::_-=}#; -" e~ ;.-; F'~ __ ,,, \<'-, ;- /,; -,-Co, x- :'~;~-:;~.:i\':':l:';L;:j1-:{1~T:;:-:;~_;;;~;'~~":"d}{~,t~~::;'tJ':>: "'_::;'Y.-h:~;:<,:;?f{):n-'f;i" ',-- _: '",'_ '[;:, >7 :r,;:s;.,.c:.t~:,-;; :-;i;"I?'.<:'~::_C:::-_;; _'_-:"~ '_~_"'; ,V-', .. (::j:;-',\-,:~~5E;;?":-(~{\'?;ii';:;i~%:,:;;';;,1;\:~-'_ : :~:;; b;{:i kLr "'~. -M'7_____ ,~ _________ " ~~.-. ;>';j C't:· ;.; ~'~1 f< v [y/ Ch~, ;"~~K'~~~::~J.)!~t ~int pte"ew"··for······Porfa]jle'····Pliis·"'User~. ;~ "« "j:} <:",:~:~;,< ';>,"\ '-A:~Y, ~i ': ;-;';',;i~:;": .. :;-_~-,;_/_:Z\l<' <i:-;~_-:- ___'~~~:;:)'_T.:::-, :"'''<-,T:<,:,:(;:f:L::;;'' , ;:>X::-'i ;2,:"~-\-.:.:..1!'i;;7;i':.?rT,;F;'~'X?,': ,S>,C,:,'"",:,,-Y ~',~'L,<'if/,'JW:::';~,~~ -< i'i~)' oJ,: "A ,"-e, '< ':i;' ;~2'y :i ~~ }~b,~~:;:%yR,~;;¥~~t~~$;;;;,W:jitl!~.,?p;Q;S';~~;Q:l{til'. '. ""'"< 7-'-;:,:J',:Z';'; 2~,;'~~;.,:,>':-:,: '-:?'-:I:\:-,~;:- '- Publisher's Message ........................ 3 MS-DOS 4.01, Making the LS/12 Faster ....... 16 Letters . 3 Removing the Portable Vectra's Screen. .. 18 110% Stuck Interlock Switch on LS/12 . .. 18 Do Your 1989 Taxes Your HP Portable. 6 Diagnostic Software for GM Automobiles ...... 19 Hidden, Important 110 and Portable Plus Keys 8 Get HP BASIC on a PC with HTBasic ......... 24 Charging Batteries on the Portable Plus ....... 10 Zenith SupersPort to Sell Through Sears ...... 24 MS-Word Printer Drivers for the Portable Plus. .. 12 Update on Valitek Tape Backup System ....... 24 More on HP's Decision to Discontinue Parallel Port Expansion Cha..<;sis ............ -

2011 State of the News Media Report

Overview By Tom Rosenstiel and Amy Mitchell of the Project for Excellence in Journalism By several measures, the state of the American news media improved in 2010. After two dreadful years, most sectors of the industry saw revenue begin to recover. With some notable exceptions, cutbacks in newsrooms eased. And while still more talk than action, some experiments with new revenue models began to show signs of blossoming. Among the major sectors, only newspapers suffered continued revenue declines last year—an unmistakable sign that the structural economic problems facing newspapers are more severe than those of other media. When the final tallies are in, we estimate 1,000 to 1,500 more newsroom jobs will have been lost—meaning newspaper newsrooms are 30% smaller than in 2000. Beneath all this, however, a more fundamental challenge to journalism became clearer in the last year. The biggest issue ahead may not be lack of audience or even lack of new revenue experiments. It may be that in the digital realm the news industry is no longer in control of its own future. News organizations — old and new — still produce most of the content audiences consume. But each technological advance has added a new layer of complexity—and a new set of players—in connecting that content to consumers and advertisers. In the digital space, the organizations that produce the news increasingly rely on independent networks to sell their ads. They depend on aggregators (such as Google) and social networks (such as Facebook) to bring them a substantial portion of their audience. And now, as news consumption becomes more mobile, news companies must follow the rules of device makers (such as Apple) and software developers (Google again) to deliver their content. -

The Road Ahead 4

Penguin Readers Factsheets level E Teacher’s notes 1 2 3 The Road Ahead 4 by Bill Gates 5 with Nathan Myhrvold and Peter Rinearson 6 PRE-INTERMEDIATE SUMMARY he Road Ahead, published in 1995 and brought Microsoft employs more than 20,000 people in 48 T out in a new edition in 1996, touches on aspects countries of the world. of life close to everyone. Bill Gates, famous across When Gates and Allen first set up in business, they the world for his successful business, Microsoft, gives learned as they went along. Paul Allen admits that “our readers a fascinating insight into how personal computers management style was a little loose in the beginning. We are in the future going to change our lives still further and both took part in every decision. If there was a difference how the Internet will continue to evolve. Optimistic and between our roles, I was probably the one always pushing enthusiastic, Bill Gates takes the reader into a world of the a little bit in terms of new technology and new products, near future. This is a world where less paper is used, and Bill was more interested in doing negotiations and THE ROAD AHEAD where teachers share their work and reach more students, contracts and business deals.” where businesses hold meetings across the world without anyone leaving their offices, and where someone’s house Paul Allen left the company in 1983 when he became ill can recognize them and choose their favorite music as with Hodgkins Disease. He was badly missed by Bill they enter. -

Ever Onward: the Frontier Myth and the Information Age Jack Shuler

Fast Capitalism ISSN 1930-014X Volume 1 • Issue 1 • 2005 doi:10.32855/fcapital.200501.007 Ever Onward: The Frontier Myth and the Information Age Jack Shuler In 1995 Bill Gates, the software pioneer, entrepreneur, billionaire, and now philanthropist, offered a critique of a term made famous by former vice-president and champion of the Internet[1] Al Gore. In The Road Ahead, Gates argues that the term for the emerging communication network, the “information superhighway,” is ill-conceived. He writes, “The phrase suggests landscape and geography, a distance between points…When you hear the phrase ‘information superhighway,’ rather than seeing a road imagine a marketplace or exchange” (Gates, Myhrvold, and Rinearson 1995: 5-6). Both metaphors are apropos. The former describes a network crisscrossing a landscape, with on-ramps and off-ramps, exits and entrances, stores and outposts, commerce and society intertwined along the route. The latter suggests a location for trade in goods and ideas where the conversation is as important as the business at hand. Both metaphors describe places. In an essay published the same year as The Road Ahead, media critic Laura Miller suggests that “The Net… occupies precisely no physical space (although the computers and phone lines that make it possible do). It is a completely bodyless, symbolic thing with no discernible boundaries or location” (Miller 2001: 215). This assertion appears alongside a critique of contemporary use of language that is part and parcel of the frontier myth—the belief that the presence of open space coupled with a pioneering and entrepreneurial spirit best explains the growth of the United States. -

Fall 2007 Guests and for Locals Looking to Explore and Learn About Our Amazing City and Its Rich, Diverse History

Chinatown Discovery Neighborhood Tours Discover Seattle’s Chinatown! A cultural experience that is unique, historical, educational and fun. Learn about Seattle’s Asian community from local guides and experience Asian cultures first-hand in Seattle’s Chinatown- International District. Participants will also stroll through Asian markets and shops. Perfect for the out-of-town Members Newsletter Fall 2007 guests and for locals looking to explore and learn about our amazing city and its rich, diverse history. Capital Campaign in its Final Stretch Thanks to the generous donation of Vi Mar, Chinatown Together with your support, we have raised $21.5 million or In addition to the Donor Staircase Art Installation designed Discovery Tours is now affiliated with the Wing Luke 93% of the capital campaign goal! by artist Susie Jungune Lee recognizing gifts from $10,000- Asian Museum. However, as we approach our final three months of the $99,999, a second art installation proposal submitted by local Chinatown Discovery walking tours will continue campaign, every gift counts in order to successfully complete visual artist Saya Moriyasu has been selected to permanently through the Wing Luke Asian Museum’s transition period our $900,000 Kresge Foundation Challenge Grant by November acknowledge gifts in the $5,000-$9,999 range. from December 2007 through May 2008. 2007. This means that every $3 donated will bring in $1 While still early in the design process, Saya’s “Celebration” For more information, visit www.seattlechinatowntour. toward our Kresge award. Please continue to help spread the is a windchime inspired by the inviting and relaxing sounds of com or call (206) 623-5124 to arrange a tour for adults, word to push us to our final goal of $23.2 million! water and bells and the lively colors shared by many community families and school groups. -

Schumpeterian Competition and Diseconomies of Scope; Illustrations from the Histories of Microsoft and IBM

Schumpeterian competition and diseconomies of scope; illustrations from the histories of Microsoft and IBM Timothy Bresnahan Shane Greenstein Rebecca Henderson Working Paper 11-077 Copyright © 2011 by Timothy Bresnahan, Shane Greenstein, Rebecca Henderson Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Schumpeterian competition and diseconomies of scope; illustrations from the histories of Microsoft and IBM. Timothy Bresnahan, Shane Greenstein, Rebecca Henderson* Abstract: We address a longstanding question about the causes of creative destruction. Dominant incumbent firms, long successful in an existing technology, are often much less successful in new technological eras. This is puzzling, since a cursory analysis would suggest that incumbent firms have the potential to take advantage of economies of scope across new and old lines of business and, if economies of scope are unavailable, to simply reproduce entrant behavior by creating a “firm within a firm.” There are two broad streams of explanation for incumbent failure in these circumstances. One posits that incumbents fear cannibalization in the market place, and so under-invest in the new technology. The second suggests that incumbent firms develop organizational capabilities and cognitive frames that make them slow to “see” new opportunities and that make it difficult to respond effectively once the new opportunity is identified. In this paper we draw on two of the most important historical episodes in the history of the computing industry, the introduction of the PC and of the browser, to develop a third hypothesis. -

Bill Gates- Biography.Pdf

William H. Gates Chairman Microsoft Corporation William (Bill) H. Gates is chairman of Microsoft Corporation, the worldwide leader in software, services and solutions that help people and businesses realize their full potential. Microsoft had revenues of US$39.79 billion for the fiscal year ending June 2005, and employs more than 61,000 people in 102 countries and regions. On June 15, 2006, Microsoft announced that effective July 2008 Gates will transition out of a day-to-day role in the company to spend more time on his global health and education work at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. After July 2008 Gates will continue to serve as Microsoft’s chairman and an advisor on key development projects. The two-year transition process is to ensure that there is a smooth and orderly transfer of Gates’ daily responsibilities. Effective June 2006, Ray Ozzie has assumed Gates’ previous title as chief software architect and is working side by side with Gates on all technical architecture and product oversight responsibilities at Microsoft. Craig Mundie has assumed the new title of chief research and strategy officer at Microsoft and is working closely with Gates to assume his responsibility for the company’s research and incubation efforts. Born on Oct. 28, 1955, Gates grew up in Seattle with his two sisters. Their father, William H. Gates II, is a Seattle attorney. Their late mother, Mary Gates, was a schoolteacher, University of Washington regent, and chairwoman of United Way International. Gates attended public elementary school and the private Lakeside School. There, he discovered his interest in software and began programming computers at age 13. -

Discover Your Palate. Savor the Art. a Splash of Art, a Sprinkle of Food, and a Dash of Good Company Are Our Main Ingredients for the Evening

member’s newsletter | winter 2009 Discover your palate. Savor the art. A splash of art, a sprinkle of food, and a dash of good company are our main ingredients for the evening. Saturday, April 4, 2009 Bell Harbor International Conference Center | 2211 Alaskan Way in Seattle’s Pier 66 For tickets, call (206) 623.5124 ext. 107 ome celebrate the Wing Luke Asian Museum’s Year of New Beginnings 2009 Annual CDinner and Auction featuring the Art of Cuisine with celebrity emcee Mark Dacascos, Chairman of Iron Chef America. Barry Wong photography Taste your way through a selection of art-inspired appetizers created by local chefs, learn about their inspirations, and vote for your favorite! Culinary creations will be presented by Gerold Castro of Kawali Grill, Gian Jaswal of India Bistro, Alex Nguyen of Saigon Bistro, Alan Quan of Four Seas, Christina Scholz of ATA Farms, and Rachel Yang of Joule. Artists featured in the auction include: James Lawrence Ardeña, Alfredo Arreguin, Arturo Artorez, Barbara Barnes Allen, Sonja Blomdahl, Romson Bustillo, Virginia Causey, MalPina Chan, Diem Chau, Don de Llamas, Janell de Varona, Marita Dingus, Jack Eng, Catherine Foster, Akiko Graham, Aaliyah Gupta, Amy Hara, Mark Horiuchi, late Paul Horiuchi, Etsuko Ichikawa, Mary Ishii, Louise Kikuchi, Fumiko Kimura, Marilyn Kreft, Bobbie Larson, Alan Lau, Gwendolyn Lee, Cheryll Leo-Gwin, Kathy Liao, Lee Sik Lim, Lolan Lo Cheng, Jane Molnar McCormmach, Benjamin Moore, Saya Moriyasu, Benjamin Muchnick, Maureen Murphy Herward, Mira Nakashima, Jennifer Nerad, Thu Nguyen, Corrine Okada Takara, Nori Okamura, Reid Ozaki, Tommer Peterson, Michael Roco, Michael Ryan, Britt Rynearson, June Sekiguchi, Joby Shimomura, Evert Sodergren, Aki Sogabe, late Robert Sperry, Taiko Suzuki, Teresa Tamura, Gerard Tsutakawa, late Windsor Utley, ZZ Wei, Barry Wong, Rick Wong, Stewart Wong, Junko Yamamoto, and Thomas Zalewski. -

BY Michael R. Fancher

FOR RELEASE MARCH 19, 2011 BY Michael R. Fancher FOR MEDIA OR OTHER INQUIRIES: Amy Mitchell, Director, Journalism Research 202.419.4372 www.pewresearch.org RECOMMENDED CITATION Pew Research Center, March, 2011, “Seattle: A New Media Case Study” 1 PEW RESEARCH CENTER About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping America and the world. It does not take policy positions. The center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, content analysis and other data-driven social science research. It studies U.S. politics and policy; journalism and media; Internet, science and technology; religion and public life; Hispanic trends; global attitudes and trends; and U.S. social and demographic trends. All of the center’s reports are available at www.pewresearch.org. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts, its primary funder. © Pew Research Center 2011 www.pewresearch.org 2 PEW RESEARCH CENTER Seattle: A New Media Case Study Seattle, perhaps more than any other American city, epitomizes the promise and challenges of American journalism at the local level. In the last few years, it has experienced both a sharp loss of traditional news resources and an exciting rise in new journalistic enterprises and inventive collaborations between traditional and emerging media (see Appendix for more about these sites). A New America Foundation case study of Seattle’s news ecosystem describes it as “a digital community still in transition.” A new, vibrant media scene is emerging. But it also may not take hold. Consider first the contraction.