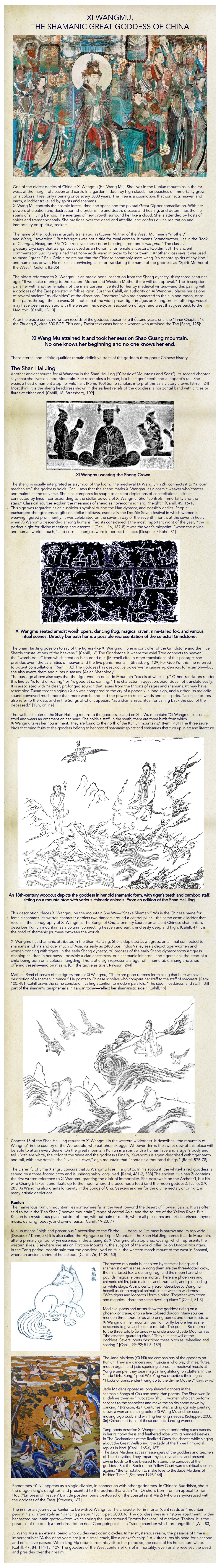

Xi Wangmu, the Shamanic Great Goddess of China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cultural and Religious Background of Sexual Vampirism in Ancient China

Theology & Sexuality Volume 12(3): 285-308 Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications London, Thousand Oaks CA, New Delhi http://TSE.sagepub.com DOI: 10.1177/1355835806065383 The Cultural and Religious Background of Sexual Vampirism in Ancient China Paul R. Goldin [email protected] Abstract This paper considers sexual macrobiotic techniques of ancient China in their cultural and religious milieu, focusing on the text known as Secret Instructions ofthe Jade Bedchamber, which explains how the Spirit Mother of the West, originally an ordinary human being like anyone else, devoured the life force of numerous young boys by copulating with them, and there- by transformed herself into a famed goddess. Although many previous studies of Chinese sexuality have highlighted such methods (the noted historian R.H. van Gulik was the first to refer to them as 'sexual vampirism'), it has rarely been asked why learned and intelligent people of the past took them seriously. The inquiry here, by considering some of the most common ancient criticisms of these practices, concludes that practitioners did not regard decay as an inescapable characteristic of matter; consequently it was widely believed that, if the cosmic processes were correctly under- stood, one could devise techniques that may forestall senectitude indefinitely. Keywords: sexual vampirism, macrobiotics, sex practices, Chinese religion, qi, Daoism Secret Instructions ofthe Jade Bedchamber {Yufang bijue S Ml^^) is a macro- biotic manual, aimed at men of leisure wealthy enough to own harems, outlining a regimen of sexual exercises that is supposed to confer immor- tality if practiced over a sufficient period. The original work is lost, but substantial fragments of it have been preserved in Ishimpo B'O:^, a Japanese chrestomathy of Chinese medical texts compiled by Tamba Yasuyori ^MMU (912-995) in 982. -

Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony

Cultural and Religious Studies, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 7, 386-402 doi: 10.17265/2328-2177/2020.07.002 D DAVID PUBLISHING Rebuilding the Ancestral Temple and Hosting Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer and Enlightenment Ceremony Wu Hui-Chiao Ming Chuan University, Taiwan Kuo, Yeh-Tzu founded Taiwan’s Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple in 1970. She organized more than 200 worshipers as a group named “Taiwan Tsu Huei Temple Queen Mother of the West Delegation to China to Worship at the Ancestral Temples” in 1990. At that time, the temple building of the Queen Mother Palace in Huishan of Gansu Province was in disrepair, and Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu made a vow to rebuild it. Rebuilding the ancestral temple began in 1992 and was completed in 1994. It was the first case of a Taiwan temple financing the rebuilding of a far-away Queen Mother Palace with its own donations. In addition, Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple celebrated its 45th anniversary and hosted Yiwei Yuanheng Lizhen Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Momentous and Fortuitous Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) in 2015. This is the most important and the grandest blessing ceremony of Taoism, a rare event for Taoism locally and abroad during this century. Those sacred rituals were replete with unprecedented grand wishes to propagate the belief in Queen Mother of the West. Stopping at nothing, Queen Mother’s love never ceases. Keywords: Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, Temple Master Kuo, Yeh-Tzu, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond, Daluo Tiandi Qingjiao (Daluo Heaven and Earth Prayer Ceremony) Introduction The main god, Golden Mother of the Jade Pond (Golden Mother), enshrined in Sung Shan Tsu Huei Temple, is the same as the Queen Mother of the West, the highest goddess of Taoism. -

Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue11, Ver. 6 (Nov. 2016) PP 39-46 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Mythical Image of “Queen Mother of the West” and Metaphysical Concept of Chinese Jade Worship in Classic of Mountains and Seas Juan Wu1 (School of Foreign Language,Beijing Institute of Technology, China) Abstract: This paper focuses on the mythological image, the Queen Mother of the West in Classic of Mountains and Seas, to explore the hiding history and mental reality behind the fantastic literary images, to unveil the origin of jade worship, which plays an significant role in the 8000-year-old history of Eastern Asian jade culture, to elucidate the genetic mechanism of the jade worship budded in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, so that we can have an overview of the tremendous influence it has on Chinese civilization, and illustrate its psychological role in molding the national jade worship and promoting the economic value of jade business. Key words: Mythical Image, Mythological Concept, Jade Worship, Classic of Mountains and Seas I. WHITE JADE RING AND QUEEN MOTHER OF THE WEST As for the foundation and succession myths of early Chinese dynasties, Allan holds that “Ancient Chinese literature contains few myths in the traditional sense of stories of the supernatural but much history” (Allan, 1981: ix) and “history, as it appears in the major texts from the classical period of early China (fifth-first centuries B.C.),has come to function like myth” (Allan, 1981: 10). While “the problem of myth for Western philosophers is a problem of interpreting the meaning of myths and the phenomenon of myth-making” as Allan remarks, “the problem of myth for the sinologist is one of finding any myths to interpret and of explaining why there are so few.” (Allen, 1991: 19) To decode why white jade enjoys a prominent position in the Chinese culture, the underlying conceptual structure and unique culture genes should be investigated. -

Analysis of Constructive Effect That Amplification and Omission Have on the Power Differentials—Taking Eileen Chang's Chines

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 588-592, March 2014 © 2014 ACADEMY PUBLISHER Manufactured in Finland. doi:10.4304/tpls.4.3.588-592 Analysis of Constructive Effect That Amplification and Omission Have on the Power Differentials—Taking Eileen Chang’s Chinese-English Self-translated Novels as Examples Hao He Gan Su Normal University for Nationalities, Hezuo, Gansu, 747000, China Xiaoli Liu Gan Su Normal University for Nationalities, Hezuo, Gansu, 747000, China Abstract—By taking Eileen Chang’s two Chinese-English self-translated novels as examples, this paper analyzes the construction effect that employment of amplification and omission has on the asymmetrical power relationships from four aspects of critical discourse analysis: classification system, transitivity system, modality system and transformation system. The conclusion is that the author-translator’s adoption of amplification and omission serves for the construction of asymmetrical power relationships, which has negative influence on cultural communication based upon equality between the west and the east. Index Terms—Eileen Chang, Chinese-English self-translation, amplification and omission, critical discourse analysis Eileen Chang was a legendary writer in Chinese literature history in 20th century but few people know that she is also an excellent translator. She has translated many English novels including Hemingway’s The Old man and The Sea and some of her own works. In recent years, the research on Eileen Chang is very hot whereas the research on her translation, especially on her self-translation is limited. It is easy for us to take for granted that it should be the most faithful that the author translates his/her own works. -

Chinese at Home : Or, the Man of Tong and His Land

THE CHINESE AT HOME J. DYER BALL M.R.A.S. ^0f Vvc.' APR 9 1912 A. Jt'f, & £#f?r;CAL D'visioo DS72.I Section .e> \% Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 https://archive.org/details/chineseathomeorm00ball_0 THE CHINESE AT HOME >Di TSZ YANC. THE IN ROCK ORPHAN LITTLE THE ) THE CHINESE AT HOME OR THE MAN OF TONG AND HIS LAND l By BALL, i.s.o., m.r.a.s. J. DYER M. CHINA BK.K.A.S., ETC. Hong- Kong Civil Service ( retired AUTHOR OF “THINGS CHINESE,” “THE CELESTIAL AND HIS RELIGION FLEMING H. REYELL COMPANY NEW YORK. CHICAGO. TORONTO 1912 CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE . Xi CHAPTER I. THE MIDDLE KINGDOM . .1 II. THE BLACK-HAIRED RACE . .12 III. THE LIFE OF A DEAD CHINAMAN . 21 “ ” IV. T 2 WIND AND WATER, OR FUNG-SHUI > V. THE MUCH-MARRIED CHINAMAN . -45 VI. JOHN CHINAMAN ABROAD . 6 1 . vii. john chinaman’s little ones . 72 VIII. THE PAST OF JOHN CHINAMAN . .86 IX. THE MANDARIN . -99 X. LAW AND ORDER . Il6 XI. THE DIVERSE TONGUES OF JOHN CHINAMAN . 129 XII. THE DRUG : FOREIGN DIRT . 144 XIII. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN EATS AND DRINKS . 158 XIV. JOHN CHINAMAN’S DOCTORS . 172 XV. WHAT JOHN CHINAMAN READS . 185 vii Contents CHAPTER PAGE XVI. JOHN CHINAMAN AFLOAT • 199 XVII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN TRAVELS ON LAND 2X2 XVIII. HOW JOHN CHINAMAN DRESSES 225 XIX. THE CARE OF THE MINUTE 239 XX. THE YELLOW PERIL 252 XXI. JOHN CHINAMAN AT SCHOOL 262 XXII. JOHN CHINAMAN OUT OF DOORS 279 XXIII. JOHN CHINAMAN INDOORS 297 XXIV. -

Luminary Buddhist Nuns in Contemporary Taiwan: a Quiet Feminist Movement

Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 Luminary Buddhist Nuns in Contemporary Taiwan: A Quiet Feminist Movement Wei-yi Cheng Department of the Study of Religions School of African and Asian Studies [email protected] ABSTRACT: Luminary order is a well-respected Buddhist nuns’ order in Taiwan. In this essay, I will examine the phenomenon of Luminary nuns from three aspects: symbol, structure, and education. Through the examination of the three aspects, I will show why the phenomenon of Luminary nuns might be seen as a feminist movement. Although an active agent in many aspects, I will also show that the success of Luminary nuns has its roots in the social, historical, and economic conditions in Taiwan. One notable feature of Buddhism in contemporary Taiwan is the large number of nuns. It is estimated that between 70 and 75 percent of the Buddhist monastic members are nuns; many of them have a higher education background.1 Many Buddhist nuns hold high esteem in the society, such as the artist and founder of Hua Fan University, bhikṣuṇī Hiu Wan, and the founder of one of the world’s biggest Buddhist organizations, bhikṣuṇī Cheng-yen.2 While bhikṣuṇī Hiu Wan and bhikṣuṇī Cheng-yen are known as highly-achieved individuals, the nuns of the Luminary nunnery are known collectively as a group. During my fieldwork in Taiwan in 2001, many informants mentioned Luminary nuns to me as group of nuns well-trained in Buddhist doctrines, practices, and precepts. The term Lumi- nary nuns seems to be equivalent to the image of knowledgeable and disciplined Buddhist nuns. -

Learning Guide

Once Upon a Moon Once Upon a Moon In partnership with the National Air & Space Museum Recommended for ages 3-7 PreK to Grade 2 A Reproducible Learning Guide for Educators This guide is designed to help educators prepare for, enjoy, and discuss Once Upon a Moon It contains background, discussion questions and activities appropriate for ages 3-7. Programs Are Made Possible, In Part, By Generous Gifts From: The Nora Roberts Foundation Smithsonian Women's Committee DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities Sommer Endowment Smithsonian Youth Access Grants Program Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Discovery Theater ● P.O. Box 23293, Washington, DC ● www.discoverytheater.org Like us on Facebook ● Instagram: SmithsonianDiscoveryTheater ● Twitter: Smithsonian Kids Once Upon a Moon 2 Fun Facts about the Moon! • The Moon is the Earth’s only natural satellite. A natural satellite is a space body that orbits a planet, a planet like object or an asteroid. • It is the fifth largest moon in the Solar System. • The average distance from the Moon to the Earth is 238857 miles. • The Moon orbits the Earth every 27.3 days. • The first person to set foot on the Moon was Neil Armstrong. • The Moon is very hot during the day but very cold at night. The average surface temperature of the Moon is 107 degrees Celsius during the day and -153 degrees Celsius at night. • The Earth’s tides are largely caused by the gravitational pull of the Moon. Moon Myths from Around the World Chang’e: The Chinese Goddess of the Moon The Jade Emperor, ruler of Heaven, had ten unruly sons. -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

TAOISM the Quest for Immortality

TAOISM The Quest For Immortality JOHN BLOFELD MANDALA UNWIN PAPERBACKS London Boston Sydney Wellington To Huang Chung-liang ( Al Huang) of the Living Tao Foundation and to my daughter Hsueh-Ch'an (Susan), also called Snow Beauty John Blofeld devoted a lifetime to the study of Eastern traditions, was fluent in Chinese c;1nd wrote several books. He is well known for his translations from Chinese, including his popular I Ching: The Chinese Book of Change. He died in Thailand in 1987. Foreword Taoism - ancient, mysterious, charmingly poetic- born amidst the shining mists that shroud civilisation's earliest beginnings, is a living manifestation of an antique way of life almost vanished from the world. Now that the red tide has engulfed its homeland, who knows its further destiny or whether even tiny remnants of it will survive? For people who recognise the holiness of nature and desire that spirit should triumph over the black onrush of materialism, it is a treasure house wherein, amidst curiously wrought jewels of but slight intrinsic value, are strewn precious pearls and rare, translucent jades. Folklore, occult sciences, cosmology, yoga, meditation, poetry, quietist philosophy, exalted mysticism- it has them all. These are the gifts accumulated by the children of the Yellow Emperor during no less than five millenia. The least of them are rainbow-hued and the very stuff of myth and poetry; the most precious is a shining fulfilment of man's spiritual destiny, a teaching whereby humans can ascend from mortal to immortal state and dwell beyond -

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES in ABC-CLIO’S Handbooks of World Mythology

Handbook of Chinese Mythology TITLES IN ABC-CLIO’s Handbooks of World Mythology Handbook of Arab Mythology, Hasan El-Shamy Handbook of Celtic Mythology, Joseph Falaky Nagy Handbook of Classical Mythology, William Hansen Handbook of Egyptian Mythology, Geraldine Pinch Handbook of Hindu Mythology, George Williams Handbook of Inca Mythology, Catherine Allen Handbook of Japanese Mythology, Michael Ashkenazi Handbook of Native American Mythology, Dawn Bastian and Judy Mitchell Handbook of Norse Mythology, John Lindow Handbook of Polynesian Mythology, Robert D. Craig HANDBOOKS OF WORLD MYTHOLOGY Handbook of Chinese Mythology Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner Santa Barbara, California • Denver, Colorado • Oxford, England Copyright © 2005 by Lihui Yang and Deming An All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Yang, Lihui. Handbook of Chinese mythology / Lihui Yang and Deming An, with Jessica Anderson Turner. p. cm. — (World mythology) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-806-X (hardcover : alk. paper) — ISBN 1-57607-807-8 (eBook) 1. Mythology, Chinese—Handbooks, Manuals, etc. I. An, Deming. II. Title. III. Series. BL1825.Y355 2005 299.5’1113—dc22 2005013851 This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. Visit abc-clio.com for details. ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116–1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

The Main Characteristics of Arabic Borrowed Words in Bahasa Melayu

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume 2, Number 4. October 2018 Pp.232- 260 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no4.18 The Main Characteristics of Arabic Borrowed Words in Bahasa Melayu Khairi O. Al-Zubaidi Executive Director Arab Society of English Language Studies Abstract Bahasa Melayu (Malaysian Language) like other languages has borrowed a number of words from other languages. This paper presents a study of Arabic borrowed words in Bahasa Melayu. It illustrates the main characteristics of the Arabic borrowed words: nouns of different types, adjectives, astrology, sciences, finance, trade, commerce, religious words and daily expressions. The researcher brought together ten categories of loan words (in three languages, Malay, Arabic and English). In conclusion, the researcher finds out that the main stream of Arabic borrowed words in Bahasa Melayu is due to the large influence of Islam. This study will provide the groundwork for further researches which will lead to enrich the linguistics and Islamic studies. Keywords: Arabic, Bahasa Melayu, borrowed words, Glorious Qur’an, influence of Islam, Malay Cites as: Al-Zubaidi, K.O. (2018). The Main Characteristics of Arabic Borrowed Words in Bahasa Melayu. Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies, 2 (4), 232- 260. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no4.18 Arab World English Journal for Translation & Literary Studies 232 eISSN: 2550-1542 |www.awej-tls.org AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies Volume, 2 Number 4. October 2018 The Main Characteristics of Arabic Borrowed Words in Bahasa Melayu Al-Zubaidi Introduction: Historical Background 1.1. Malay and Islam There is a debate about the exact date of Islam’s appearance in South East Asia.