Developing a Strategy for Emerging Adults to Transition Into the Overall Community of Grace Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rental Song List

Song no Title 1 Syndicate 2 Love Me 3 Vanilla Twilight 4 History 5 Blah Blah Blah 6 Odd One 7 There Goes My Baby 8 Didn't You Know How Much I Love You 9 Rude Boy 10 The Good Life 11 Billionaire 12 Between The Lines 13 He Really Thinks He's Got It 14 If It's Love 15 Mockingbird 16 Your Love 17 Crazy Town 18 You Look Better When I'm Drunk 19 Animal 20 September 21 It's Gonna Be 22 Dynamite 23 Misery 24 Beauty In The World 25 Crow & The Butterfly 26 DJ Got Us Fallin' In Love 27 Touch 28 Someone Else Calling You Baby 29 If I Die Young 30 Just The Way You Are 31 Like A G6 32 Dog Days Are Over 33 Home 34 Little Lion Man 35 Nightmare 36 Hot Tottie 37 Jizzle 38 Lovin Her Was Easier 39 A Little Naughty Is Nice 40 Radioactive 41 One In A Million 42 What's My Name 43 Raise Your Glass 44 Hey Baby (Drop It ToThe Floor) 45 Marry Me 46 1983 47 Right Thru Me 48 Coal Miner's Daughter 49 Maybe 50 S & M 51 For The First Time 52 The Cave 53 Coming Home 54 Fu**in' Perfect 55 Rolling In The Deep 56 Courage 57 You Lie 58 Me & Tennessee 59 Walk Away 60 Diamond Eyes 61 Raining Men 62 I Do 63 Someone Like You 64 Ballad Of Mona Lisa 65 Set Fire To The Rain 66 Just Can't Get Enough 67 I'm A Honky Tonk Girl 68 Give Me Everything 69 Roll Away Your Stone 70 Good Man 71 Make You Feel My Love 72 Catch Me 73 Number One Hit 74 Party Rock Anthem 75 Moves Like Jagger 76 Made In America 77 Drive All Night 78 God Gave Me You 79 Northern Girl 80 The Kind You Can't Afford 81 Nasty 82 Criminal 83 Sexy & I Know It 84 Drowning Again 85 Buss It Wide Open 86 Saturday Night 87 Pumped -

Sir John Hawkwood (L'acuto) : Story of a Condottiere

' - J~" - - - - |^l rirUfriiil[jiiTlffuflfim]f^ i i THE LIBRARIES 1 | i COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY [^I | 11 I i | 1 I i General Library s I i 1 SIR JOHN HAWKWOOD. Only Five hundred copies have been printed of Sir John Hawkwood, " one hundred reserved for presentation to the Public Libraries, the Press, and Friends .• and Four hundred numbered copies for the Public of which this is N° 336. jS^jA^Mfr S I It JOHN HAWKWOOD (/: act TO). STORY OF A CONDOTTIERE I'KANSLATKI' FROM 11IK ITALIAN JOHN TEMPLE-LEADER. Esq. & Sis. GIUSEPPE MARCOTTI BY LEADER SCOTT. ITonbon, T. FISHER UN WIN 26. PATERNOSTBB SQUARE. 1889. [AN rights reserved.] L / FLORENi i PRINTED BY <. BARBERA, VIA FAENZA, 66 ; PREFACE. nemo ami \v- 'INK'S. The hi orj of.the mercenarj companies in ttalj ao longer re- mains to be told; if having been published in 1844 by Ercole Ricotti howe sive monographs on the same subject hi ve produced such a wealth of information from new sources thai Ri- i • cotti's work, . dmosi requires to be rewritten. The Archicio Stortco Italiano has already recognised this by dedicat- ing an entire volume to Documents for the history of Italian war\ from tin 13"' to the 16"' centuries collected by Giuseppe Canestrini. These re oi Sfreat importance; but even taking into account all we owe to them, and to all thai later historical researches have brought to light, the theme is not yet exhausted: truth is like happiness, and though as we approach we see it shining mure intensely, and becom- ing clearer in outline, yel we can never feel, thai we have obtained full possession of it. -

Men for Change

STAY CONNECTED >> Follow us on Twitter at @BULARIAT for breaking news updates and more Baylor Softball wins at home 6-0: pg. 6 LariatWE’RE THERE WHEN YOU CAN’T BE MARCH 30, 2017 THURSDAY BAYLORLARIAT.COM Garland testifies on new Texas Senate bill KALYN STORY Staff Writer Baylor interim President David Garland testified at a Texas Senate Higher Education Committee hearing Wednesday regarding a bill that would require Baylor to comply with state laws from which it is are currently exempt. If passed, Senate Bill 1092 would Photo Illustration by Liesje Powers | Photo Editor require any school that receives more POSITIVE PERSPECTIVE Men for Change was created in partnership with Baylor Formation, the department of multicultural affairs and the Baylor than $5 million in Tuition Equalization Counseling Center to change the way society views masculinity. Grants from the state to comply with state open records and open meetings laws. Under current law, because Baylor is a private institution, it does not have to obey state open records and open meeting laws. Men for Change During the hearing, Garland told the senators that 2,943 Baylor students receive aid from the Tuition Organization seeks to redefine society’s view on masculinity Equalization Grant, 1,597 of which are from minority populations and 962 are first-generation college students. RYLEE SEAVERS with Baylor Formation, the department of masculinity and help them figure out what that Garland said that if the bill were Staff Writer multicultural affairs and the Baylor Counseling might look like,” Ritter said. to pass as written it would only Center. -

112 Dance with Me 112 Peaches & Cream 213 Groupie Luv 311

112 DANCE WITH ME 112 PEACHES & CREAM 213 GROUPIE LUV 311 ALL MIXED UP 311 AMBER 311 BEAUTIFUL DISASTER 311 BEYOND THE GRAY SKY 311 CHAMPAGNE 311 CREATURES (FOR A WHILE) 311 DON'T STAY HOME 311 DON'T TREAD ON ME 311 DOWN 311 LOVE SONG 311 PURPOSE ? & THE MYSTERIANS 96 TEARS 1 PLUS 1 CHERRY BOMB 10 M POP MUZIK 10 YEARS WASTELAND 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT 10CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 10CC THE THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 FT. SEAN PAUL NA NA NA NA 112 FT. SHYNE IT'S OVER NOW (RADIO EDIT) 12 VOLT SEX HOOK IT UP 1TYM WITHOUT YOU 2 IN A ROOM WIGGLE IT 2 LIVE CREW DAISY DUKES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW DIRTY NURSERY RHYMES (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW FACE DOWN *** UP (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW ME SO HORNY (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 LIVE CREW WE WANT SOME ***** (NO SCHOOL PLAY) 2 PAC 16 ON DEATH ROW 2 PAC 2 OF AMERIKAZ MOST WANTED 2 PAC ALL EYEZ ON ME 2 PAC AND, STILL I LOVE YOU 2 PAC AS THE WORLD TURNS 2 PAC BRENDA'S GOT A BABY 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (EXTENDED MIX) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (NINETY EIGHT) 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE (ORIGINAL VERSION) 2 PAC CAN'T C ME 2 PAC CHANGED MAN 2 PAC CONFESSIONS 2 PAC DEAR MAMA 2 PAC DEATH AROUND THE CORNER 2 PAC DESICATION 2 PAC DO FOR LOVE 2 PAC DON'T GET IT TWISTED 2 PAC GHETTO GOSPEL 2 PAC GHOST 2 PAC GOOD LIFE 2 PAC GOT MY MIND MADE UP 2 PAC HATE THE GAME 2 PAC HEARTZ OF MEN 2 PAC HIT EM UP FT. -

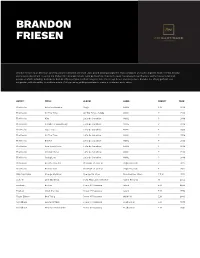

Brandon Friesen – Primary Wave Music

BRANDON FRIESEN Brandon Friesen is an American, Grammy Award nominated and multi-Juno Award winning songwriter, music producer, and audio engineer. Most recently, Brandon executive produced and co-wrote the Kooks fifth full length album, Let’s Go Sunshine. Brandon’s career has spanned over 15 years, and he has recorded and produced artists including: Nickelback, Sum 41, Billy Ray Cyrus, Everlast, Finger Eleven, Three Days Grace, and many more. Brandon is a strong guitarist and songwriter, with the ability to produce artists of all genres by guiding musicians to create a consistent sonic vision. ARTIST: TITLE: ALBUM: LABEL: CREDIT: YEAR: The Kooks Got Your Number Single AWAL P,W 2019 The Kooks All The Time All The Time - Single AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Kids Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Initials For Gainsbourg Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks tesco Disco Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks All The Time Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Believe Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Four Leaf Clover Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Chicken Bone Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Swing Low Let's Go Sunshine AWAL P 2018 The Kooks Be Who You Are The Best of...So Far Virgin Records P 2017 The Kooks Broken Vow The Best of...So Far Virgin Records P 2017 Billy Ray Cyrus Change My Mind Change My Mind Blue Cadillac Music P,E,M 2012 Sum 41 Over My Head Does This Look Infected? Island Records M 2002 Everlast Broken Power 97 Sessions Island E,M 2004 Everlast What It's Like Power 97 Sessions Island E,M 1998 Finger Eleven One Thing Power 97 Sessions Wind-Up E,M 2003 Nickelback Leader Of Men Power 97 Sessions Roadrunner E,M 1999 Nickelback How You Remind Me Power 97 Sessions Roadrunner E,M 2001. -

Aristophanes-Lysistrata.Pdf

LYSISTRATA TRANSLATOR’S NOTE The translation, which has been prepared by Ian Johnston of Malaspina University-College, Nanaimo British Columbia, Canada (now Vancouver Island University), may be distributed to students without permission and without charge, provided the source is acknowledged. There are, however, copyright restrictions on commercial publication of this text (for details consult Ian Johnston at [email protected]). Note that in the text below the numbers in square brackets refer to the lines in the Greek text; the numbers without brackets refer to the lines in the translated text. In numbering the lines of the English text, the Aristophanes translator has normally counted a short indented line with the short line Lysistrata above it, so that two short lines count as one line. The translator would like to acknowledge the valuable help provided by Alan H. Sommerstein’s edition of Lysistrata (Aris & Phillips: 1990), parti- cularly the commentary. It is clear that in this play the male characters all wear the comic phallus, which is an integral part of the action throughout. Note, too, that in several places in Lysistrata there is some confusion and debate over which speeches are assigned to which people. These moments occur, for the most part, in short conversational exchanges. Hence, there may be some Translated by Ian Johnston differences between the speakers in this text and those in other trans- Vancouver Island University lations. Nanaimo, BC Canada Aristophanes (c. 446 BC to c. 386 BC) was the foremost writer of Old Comedy in classical Athens. His play Lysistrata was first performed in Athens in 411 BC, two years after the disastrous Sicilian Expedition, where Athens suffered an enormous defeat in the continuing war with Sparta and its allies (a conflict with lasted from 431 BC to 404 BC). -

Inner Secrets of the Path

Hu 121 Inner Secrets of The Path by Sayyid Haydar Amuli Translated from the Original Arabic by Asadullah ad-Dhaakir Yate Introduction and Biographical Background In the Name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful. Praise belongs to Allah, the Lord of the worlds who in His essential divine substance is before time and ever-existent, who in His own necessary independence is the beginning and the end and whose eternity does not admit of end. Praise belongs to Him who by His essence is Him. The Beloved is He who is Allah, the Soul Being, the Beloved is Him. He is the Independent, the Eternal, who begets no one. The One, who was not begotten, without opponent or rival. He is the Possessor of Splendour, the One, the Eternal. His Oneness is not, however, of the kind to be counted. He is without likeness, existent before creation and time. There has been, nor is nothing similar to Him. He is untouched by time and place. The chapter of The Unity (in the Qur'an) is an indication of this. He is Existence from before time and without need. He is the Real and the Creator of the different essences. He is without annihilation, subsistent of Himself. He exists by His essence, the Source of Outpouring of all essences. May blessings and peace without end be on Muhammad, the first radiant manifestation of the Essence, the first of the messengers of Allah, whose reality is the radiant point of manifestation of the essence of the Lord of the Worlds, who is himself also the seal of His prophets, and on his caliph and successor, the greatest of caliphs, the most excellent of guardians and the seal of spiritual authority from the Maker of the heavens and the earth, the Commander of the Faithful and the just divider of people between the Fire and the Garden, the yamin of Allah' - one of Allah's people of the right - as mentioned in the Qur'an. -

In the Flesh: Authenticity, Nationalism, and Performance on the American Frontier, 1860-1925

IN THE FLESH: AUTHENTICITY, NATIONALISM, AND PERFORMANCE ON THE AMERICAN FRONTIER, 1860-1925 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jefferson D. Slagle, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Chadwick Allen, Adviser Professor Jared Gardner ________________________________ Professor Susan S. Williams Adviser English Graduate Program Copyright by Jefferson D. Slagle 2006 ABSTRACT Representations of the frontier through the early twentieth century have been subject to two sets of critical criteria: the conventional aesthetic expectations of the particular genres and forms in which westerns are produced, and the popular cultural demand for imitative “authenticity” or faithfulness to the “real west.” “In the Flesh” probes how literary history is bound up with the history of performance westerns that establish the criteria of “authenticity” that text westerns seek to fulfill. The dissertation demonstrates how the impulse to verify western authenticity is part of a post-Civil War American nationalism that locates the frontier as the paradigmatic American socio-topography. It argues westerns produced in a variety of media sought to distance themselves from their status as art forms subject to the critical standards of particular genres and to represent themselves as faithful transcriptions of popular frontier history. The primary signifier of historicity in all these forms is the technical ability to represent authentic bodies capable of performing that history. Postbellum westerns, in short, seek to show their audiences history embodied “in the flesh” of western performers. “In the Flesh” is therefore divided into two sections: the first analyzes performance westerns, including stage drama, Wild West, and film, that place bodies on display for the immediate appraisal of audiences. -

World War I Diary of Philip H. English the Revised Diary of a Lieutenant of the Connecticut National Guard. 1917 – 18 – 19

World War I Diary of Philip H. English The Revised Diary of a Lieutenant of the Connecticut National Guard. 1917 – 18 – 19. Image: New Haven Museum th World War I Diary of Philip H. English (*D 570.3 26 E64 Vol. 1) Transcribed by Jenna Fortunati, January 2017 Spelling and Grammar is as appears in original document. Page numbers in parenthesis, example: (p4) denote the original page numbers Property of the New Haven Museum. Reproduction is prohibited without permission. National Guard: Didn’t know much, but knew something, Learned while other men played, Didn’t delay for commissions; Went while other men stayed. Took no degrees up at Plattsburg, Needed too soon for the game Ready at hand to be asked for, Orders said, “Come” – and they came. Didn’t get bars on their shoulders, Or three months to see if they could; Didn’t get classed with the reg’lars Or told they were equally good. Just got a job and got busy, Awkward they were, but intent, Filling no claim for exemption, Orders said, “Go” – and they went. Didn’t get farewell processions, Didn’t get newspaper praise, Didn’t escape the injunction To mend in extension their ways. Workbench and counter and roll-top, Dug in and minding their chance, Orders said: “First line of the trenches!” They’re holding them – somewhere in France. “National Guard” by R.F. Andrews, published in Life, 1918 (p1) th World War I Diary of Philip H. English (*D 570.3 26 E64 Vol. 1) Transcribed by Jenna Fortunati, January 2017 Spelling and Grammar is as appears in original document. -

Montana Kaimin, March 25, 2011 Students of the Niu Versity of Montana, Missoula

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Associated Students of the University of Montana Montana Kaimin, 1898-present (ASUM) 3-25-2011 Montana Kaimin, March 25, 2011 Students of The niU versity of Montana, Missoula Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper Recommended Citation Students of The nivU ersity of Montana, Missoula, "Montana Kaimin, March 25, 2011" (2011). Montana Kaimin, 1898-present. 5412. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/studentnewspaper/5412 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Associated Students of the University of Montana (ASUM) at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Montana Kaimin, 1898-present by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MK fridaykaimin Dream Catcher Friday, March 25, 2011 Volume CX111 Issue 84 www.montanakaimin.com Montana Kaimin 2 OPINION Friday, March 25, 2011 EDITORIAL KAIMIN COMICS Working for peanuts by Jed Nussbaum, Arts+Culture Editor I’ve had a job every summer since I was 11 years old. For the past eight years, I’ve worked construction, doing everything from pounding nails to fixing plumbing leaks. I’m still not much of a car- penter, and I probably never will be. But I understand what it’s like to put in long days of hard work in the summer heat. Most college students go to school to avoid labor jobs. They work menial, underpaid positions in the fast food industry and behind the bar, but these positions are temporary in their mind — just pay- ing the bills before that magical degree transports them to a realm far, far away from backbreaking manual labor jobs. -

Whit Stillman's DAMSELS in DISTRESS

presents A Westerly Films Production Whit Stillman’s DAMSELS IN DISTRESS 2011 Venice Film Festival, Closing Night 2011 Toronto International Film Festival www.damselsindistressmovie.com 99 min | Release Date (NY/LA): 04/06/2012 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Betsy Rudnick Alexandra Glazer Carmelo Pirrone Joanna Pinker Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 250 W. 49th St, Ste 704 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax CAST Violet GRETA GERWIG Charlie ADAM BRODY Lily ANALEIGH TIPTON Rose MEGALYN ECHIKUNWOKE Heather CARRIE MacLEMORE Xavier HUGO BECKER Frank RYAN METCALF Thor BILLY MAGNUSSEN Priss CAITLIN FITZGERALD Jimbo JERMAINE CRAWFORD Debbie AUBREY PLAZA Rick DeWolfe ZACH WOODS Freak Astaire NICK BLAEMIRE Positive Polly AJA NAOMI KING Mad Madge ALIA SHAWKAT Alice MEREDITH HAGNER Special appearances by Professor Black TAYLOR NICHOLS Carolina (Diner) CAROLYN FARINA Sharise (Diner) SHINNERRIE JACKSON Highway Worker #1 GERRON ATKINSON Highway Worker #2 JONNIE LOUIS BROWN Seminar Suzanne COLLEEN DENGEL ALA Pamphlet Guy MAX LODGE Ed School Girl CLARE HALPINE Complainer Student DOMENICO D’IPPOLITO Professor Ryan DOUG YASUDA Barman JOE COOTS Groundskeeper CORTEZ NANCE, JR. Campus Cop SHAWN WILLIAMS Charlie’s Friend #1 TODD BARTELS Charlie’s Friend #2 EDWARD J. MARTIN Gladiator BRYCE BURKE D.U. Guy #1 WILL STORIE D.U. Guy #2 CHRISTOPHER ANGERMAN Cary JARED BURKE Emily Tweeter JORDANNA DRAZIN 2 Young Rose LAILA DREW Stunt Players CHAD HESSLER ASA LIEBMANN KEVIN ROGERS FILMMAKERS Written, Produced & Directed by WHIT STILLMAN Produced by MARTIN SHAFER & LIZ GLOTZER Co-Producer CHARLIE DIBE Line Producer JACOB JAFFKE Consulting Producers CECILIA KATE ROQUE & ALICIA VAN COUVERING Cinematographer DOUG EMMETT Editor ANDREW HAFITZ Music by MARK SUOZZO & ADAM SCHLESINGER Production Design ELIZABETH J. -

Basic Concepts of Family

Content Page 6.1 Cultural Value and Fashion 1 6.1.1 Design Concepts of Different Cultures 3 6.1.2 The Evolution of Historical Western Costume in the 20th 3 Century 6.1.3 National Costumes of East Asia & India 30 6.2 Factors Contributing to Fashion Trends in Local and Global 40 Context 6.2.1 Fashion Trend 40 6.2.2 The Change of Fashion 41 6.3 Fashion Designers 46 6.3.1 Exploring a Career in Fashion 46 6.3.2 Design Beliefs and Style 56 6.4 Total Image for Fashion Design 59 6.4.1 The Nature of Fashion Image 59 6.4.2 Major Fashion Styles 59 6.4.3 Use of Materials 66 6.4.4 Use of Fashion Accessories 68 6.1 Cultural Value and Fashion Clothing has been an integral part of human life since prehistoric time. Throughout history, clothing has provided adornment, modesty, protection, identification and status. It has also reflected the change of our geographical, social, political, economic and technological development. Clothing has also played important roles in different historical and cultural events. All these different aspects also in turn contribute to the design, styling, colour or silhouettes of clothing worn by people. Customs dictate what is deemed acceptable by a society, religions and laws play a role by determining what colours and styles are allowed. For instance, for ancient Roman, tyrian purple could only be worn by Roman senators. In China, only the Emperor could wear golden yellow. In Hawaii, only high-ranking Hawaiian chiefs could wear feather cloaks and palaoas or carved whale teeth.