A Comparative Analysis of the Temples of Khajuraho and the Ruling Chandellas of India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medieval History

CONTENTS MEDIEVAL HISTORY 1. MAJOR DYNASTIES (EARLY ....... 01-22 2. EARLY MUSLIM INVASIONS ........23-26 MEDIEVAL INDIA 750-1200 AD) 2.1 Early Muslim Invasions ..................24 1.1 Major Dynasties of North ...............02 The Arab Conquest of Sindh ............... 24 India (750-1200 Ad) Mahmud of Ghazni ............................ 24 Introduction .......................................2 Muhammad Ghori ............................. 25 The Tripartite Struggle ........................2 th th The Pratiharas (8 to 10 Century) ........3 3. THE DELHI SULTANATE ................27-52 th th The Palas (8 to 11 Century) ...............4 (1206-1526 AD) The Rashtrakutas (9th to 10th Century) ....5 The Senas (11th to 12th Century) ............5 3.1 The Delhi Sultanate ......................28 The Rajaputa’s Origin ..........................6 Introduction ..................................... 28 Chandellas ........................................6 Slave/Mamluk Dynasty (Ilbari ............ 28 Chahamanas ......................................7 Turks)(1206-1526 AD) Gahadvalas ........................................8 The Khalji Dynasty (1290-1320 AD) ..... 32 Indian Feudalism ................................9 The Tughlaq Dynasty (1320-1414 AD) .. 34 Administration in Northern India ........ 09 The Sayyid Dynasty ........................... 38 between 8th to 12th Century Lodi Dynasty .................................... 38 Nature of Society .............................. 11 Challenges Faced by the Sultanate ...... 39 Rise -

Patharya Granite Deposit of M/S Khajuraho Minerals Pvt. Ltd Executive Summary

Patharya Granite Deposit of M/s Khajuraho Minerals Pvt. Ltd Executive Summary EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.0 INTRODUCTION M/s. Khajuraho Minerals is a Pvt. Ltd company. This is a fresh mine and the mining of granite is proposed over an area of 4.99 Ha. The PL deed was executed and registered on 27.08.2011 for 2 years PL period. The area under reference has been granted under Quarry lease to the applicant for 30 years period under the provisions of Rule-6 of Granite Conservation and Development rules 1999. The mining plan has been approved by Directorate of Geology & Mining, Bhopal (MP). As per the MoEF, New Delhi Gazette dated 14th September 2006 amended in December 2009 & April 2011, the mining project of area less than 50 ha is categorized as category B project under 1(a) activity of EIA Notification. The Draft EIA/EMP is prepared as per the TOR granted vide letter No. 556/PS-MS/MPPCB/SEAC/TOR (98)/2012 dated 17.09.2012 (Case no.712/2012) under the EIA Notification. Further to assess the impact on environment due to the mine, it is necessary to ascertain present status of environment prevailing at the project site and proposed operation including identification and Assessment of impact on the environment. 2.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION Location: The mining lease area is in village Patharya, District Chhatarpur- Madhya Pradesh. The mining lease area falls in Survey of India Toposheet No. 54 P/ 13 Toposheet Details Latitude : 24056’32.2” to 24056’40.4” N Longitude : 79058’07.3” to 79058’18.7” E Area & production: The total Mining Lease area is 4.99 ha. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory . -

Ramayana of * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH with EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY

THE Ramayana OF * - Valmeeki RENDERED INTO ENGLISH WITH EXHAUSTIVE NOTES BY (. ^ ^reenivasa jHv$oiu$ar, B. A., LECTURER S. P G. COLLEGE, TRICHINGj, Balakanda and N MADRAS: * M. K. PEES8, A. L. T. PRKS8 AND GUARDIAN PBE8S. > 1910. % i*t - , JJf Reserved Copyright ftpfiglwtd. 3 [ JB^/to PREFACE The Ramayana of Valmeeki is a most unique work. The Aryans are the oldest race on earth and the most * advanced and the is their first ; Ramayana and grandest epic. The Eddas of Scandinavia, the Niebelungen Lied of Germany, the Iliad of Homer, the Enead of Virgil, the Inferno, the Purgatorio, and the Paradiso of Dante, the Paradise Lost of Milton, the Lusiad of Camcens, the Shah Nama of Firdausi are and no more the Epics ; Ramayana of Valmeeki is an Epic and much more. If any work can clam} to be the Bible of the Hindus, it is the Ramayana of Valmeeki. Professor MacDonell, the latest writer on Samskritha Literature, says : " The Epic contains the following verse foretelling its everlasting fame * As long as moynfain ranges stand And rivers flow upon the earth, So long will this Ramayana Survive upon the lips of men. This prophecy has been perhaps even more abundantly fulfilled than the well-known prediction of Horace. No pro- duct of Sanskrit Literature has enjoyed a greater popularity in India down to the present day than the Ramayana. Its story furnishes the subject of many other Sanskrit poems as well as plays and still delights, from the lips* of reciters, the hearts of the myriads of the Indian people, as at the 11 PREFACE great annual Rama-festival held at Benares. -

Social Impact Assessment Report

SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT Bundelkhand Expressway, District Banda, UP, India Submitted to District Collector Banda, Uttar Pradesh Social Responsibility Asia (SR Asia) 4F-CS-25 Ansal Plaza Mall, Vaishali Sector 1 Ghaziabad, Uttar Pradesh, India [email protected] 0 | P a g e S R A S I A SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Social Impact Assessment (SIA) Report is a result of the work executed by SR Asia as per the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 and UP Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Rules, 2016. The research team had extensive consultation with the officials of Department of Revenue and Land Reforms, public representatives and Project Affected Families (PAFs) of 26 villages of Banda District for collecting valuable inputs, data on local ecology, culture and socio-economic profiles. We extend our sincere thanks to all the Office of Collectorate, Department of Revenue and Land Reforms for their continuous support and cooperation. They have been extremely supportive throughout the study with respect to project related information, documents and providing guidance to the team in Banda The team is grateful to the Project Affected Families (PAFs) and local representatives for their time and feedbacks. We appreciate the efforts made by all the participants of this study and thank them for their support. Birendra Raturi International Director, SR Asia 1 | P a g e S R A S I A SIA Report of Bundelkhand Expressway Project in District Banda, UP, India TABLE OF CONTENT ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ......................................................................................................................... -

ASI Registered Tourist Guide List, MP

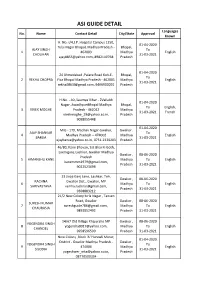

ASI GUIDE DETAIL Languages No. Name Contact Detail City/State Approval Known H. No.-I/4,J.P. Hospital Campus 1250, 01-04-2020 Tulsi Nagar Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh - Bhopal, AJAY SINGH To 1 462003 Madhya English CHOUHAN 31-03-2021 [email protected], 8982140768 Pradesh 01-04-2020 24 Ahmedabad ,Palace Road Koh-E- Bhopal, To 2 REKHA CHOPRA Fiza Bhopal Madhya Pradesh - 462001 Madhya English 31-03-2021 [email protected], 9406900091 Pradesh H.No. - 40 ,Saumya Vihar - 2Vallabh 01-04-2020 Nagar, AwadhpuriBhopal Madhya Bhopal, To English, 3 VIVEK MOGHE Pradesh - 462022 Madhya 31-03-2021 French [email protected], Pradesh 9098055448 01-04-2020 MIG - 179, Madhav Nagar Gwalior, Gwalior , AJAY SHANKAR To 4 Madhya Pradesh – 474002 Madhya English BARUA 31-03-2021 [email protected], 0751-2320203 Pradesh 46/80, Kane Bhavan, Sat Bhai Ki Goth, Laxmiganj, Lashkar, Gwalior Madhya Gwalior , 08-06-2020 Pradesh 5 HIMANSHU KANE Madhya To English [email protected], Pradesh 31-03-2021 9022523698 23 Jivaji Ganj Lane, Lashkar, Teh, Gwalior , 08-06-2020 RACHNA Gwalior Dist., Gwalior, MP 6 Madhya To English SHRIVASTAVA [email protected], Pradesh 31-03-2021 9368883212 21/2 New Colony birla Nagar , Tansen Road, Gwalior Gwalior , 08-06-2020 SURESH KUMAR 7 [email protected] , Madhya To English CHAURASIA 9893052492 Pradesh 31-03-2021 14/67 Old Village Khajuraho MP Gwalior , 08-06-2020 YOGENDRA SINGH 8 [email protected], Madhya To English CHANDEL 9958596599 Pradesh 31-03-2021 New Colony ,Block 'A' Hurawli Morar, 01-04-2020 District - Gwalior Madhya Pradesh - Gwalior , YOGENDRA SINGH To 9 474006 Madhya English SISODIA 31-03-2021 [email protected], Pradesh 08770500334 ASI GUIDE DETAIL Languages No. -

Religious Spots Within Forts and Fort Sites

Eurasian Journal of Humanities Vol. 1. Issue 1. (2015) ISSN: 2413-9947 Religious spots within forts and fort sites: a study in cultural history of Bundelkhand region in India Purushottam Singh Vikramajit Singh Sanatan Dharm College Kanpur India [email protected] Abstract Bundelkhand geographically situated in exactly the south of the Ganges plane is memorable due to the ancient references. Firstly, saints, devotees, hermits were attracted from Ganges plane towards the isolated, solitary pleasing zone of Vindhyatavi. (Singh, Rajendra, 1994, pp.1, 2) The history of Bundelkhand starts from the Chedi dynasty. (Singh, Rajendra, 1990, pp.80-85) The two famous cities of that time Shuktimati and Shahgeet are now a matter of research. After Chedis, Gupta rulers and Harsh Vardhan became the main rulers, but Chandelas were the first ruler who constructed with the capital of the region of Chedis. (Majumdar, 1951, p.252) The Bundelas and Marathas can also be regarded in this sense. There was no fort without religious spots. The religious spots in the forts of Bundelkhand were the center of belief not only for royal families but also become the center of faith and reverence of general people. Therefore these sites have gained unique and peerless fame. The religious sites within the forts played an important role in preserving and recharging the cultural heritage up to the centuries in Bundelkhand. These became the cause of cultural and religious harmony between the royal families and general people. These religious centers always released the message of prayer, peace and wish of prosperity from the royal family. Many times these temples and other spots provided the faithful with links between the royal families and general people which resulted to be the cause of welfare rule in the region. -

Jain Values, Worship and the Tirthankara Image

JAIN VALUES, WORSHIP AND THE TIRTHANKARA IMAGE B.A., University of Washington, 1974 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND SOCIOLOGY We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard / THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1980 (c)Roy L. Leavitt In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of Anthropology & Sociology The University of British Columbia 2075 Wesbrook Place Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 Date 14 October 1980 The main purpose of the thesis is to examine Jain worship and the role of the Jains1 Tirthankara images in worship. The thesis argues that the worshipper emulates the Tirthankara image which embodies Jain values and that these values define and, in part, dictate proper behavior. In becoming like the image, the worshipper's actions ex• press the common concerns of the Jains and follow a pattern that is prized because it is believed to be especially Jain. The basic orientation or line of thought is that culture is a system of symbols. These symbols are implicit agreements among the community's members, agreements which entail values and which permit the Jains to meaningfully interpret their experiences and guide their actions. -

Revised Study Guide

Spring 2021 Arts of Asia Lecture Series The Power of Images in Asian Art: Making the Invisible Visible Sponsored by the Society for Asian Art THE ENIGMA OF THE SCULPTURES AT KHAJURAHO Mary-Ann Milford-Lutzker, Carver Professor Emerita of East Asian Studies, Mills College January 22, 2021 Candella Dynasty: c. 830-1308 CE Harsha ca. 905-925 Yasovarman 925-950 Dhanga 950-999 Ganda 999-1003 Vidyadhara ca. 1004-1035 1019 and 1022: attacks by Mahmud of Ghazni Terms: alamkara: adornment, ornament, figure of speech apsara: heavenly female dancers mithuna: loving couples slesha: puns and double-entendres sura-sundaras, heavenly females vedibhanda: basement, foundation yantra: an abstract symbol for a field of energy Laksmana (Visnu) Temple, 954 CE inscription of Dhanga (double transcepts, Varaha Shrine, panchayatana design, 4 subsidiary shrines) Inscription dated 953-954 in the reign of Dhanga tells us that the temple was constructed by the Chandella King Yasovarman who died before 954, therefore, it was constructed between 930-950 and dedicated for worship in 953/4. Dedicated to the Vaikuntha form of Visnu, distinguished by 3 heads: lion, man and boar Vishvanath (Siva) Temple, late 10th C. Inscription by King Dhanga, 999 CE, refers to two lingas, an emerald and a stone one panchayatana design (main temple and 4 shrines) Kandariya Mahadeva (Siva) Temple, 1025-50 CE erected by Vidyadhara? Inscription refers to King Virimda, perhaps a name of King Vidhyadara Prabodhachandrodaya (Moonrise of Pure Knowledge) an allegorical play by Krishna Misra References: Dehejia, Vidya, The Body Adorned. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009. Desai, Devangana, Erotic Sculpture of India: A Socio-Cultural Study. -

History of India

HISTORY OF INDIA VOLUME - 2 History of India Edited by A. V. Williams Jackson, Ph.D., LL.D., Professor of Indo-Iranian Languages in Columbia University Volume 2 – From the Sixth Century B.C. to the Mohammedan Conquest, Including the Invasion of Alexander the Great By: Vincent A. Smith, M.A., M.R.A.S., F.R.N.S. Late of the Indian Civil Service, Author of “Asoka, the Buddhist Emperor of India” 1906 Reproduced by Sani H. Panhwar (2018) Preface by the Editor This volume covers the interesting period from the century in which Buddha appeared down to the first centuries after the Mohammedans entered India, or, roughly speaking, from 600 B.C. to 1200 A.D. During this long era India, now Aryanized, was brought into closer contact with the outer world. The invasion of Alexander the Great gave her at least a touch of the West; the spread of Buddhism and the growth of trade created new relations with China and Central Asia; and, toward the close of the period, the great movements which had their origin in Arabia brought her under the influences which affected the East historically after the rise of Islam. In no previous work will the reader find so thorough and so comprehensive a description as Mr. Vincent Smith has given of Alexander’s inroad into India and of his exploits which stirred, even if they did not deeply move, the soul of India; nor has there existed hitherto so full an account of the great rulers, Chandragupta, Asoka, and Harsha, each of whom made famous the age in which he lived. -

Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early Time to 8Th-12Th Century C.E)

DDCE/History (M.A)/SLM/Paper-XII Socio- Political and Administrative History of Ancient India (Early time to 8th-12th Century C.E) By Dr. Binod Bihari Satpathy 0 CONTENT SOCIO- POLITICAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF ANCIENT INDIA (EARLY TIME TO 8th-12th CENTURIES C.E) Unit.No. Chapter Name Page No Unit-I. Political Condition. 1. The emergence of Rajput: Pratiharas, Art and Architecture. 02-14 2. The Rashtrakutas of Manyakheta: Their role in history, 15-27 Contribution to art and culture. 3. The Pala of Bengal- Polity, Economy and Social conditions. 28-47 Unit-II Other political dynasties of early medieval India. 1. The Somavamsis of Odisha. 48-64 2. Cholas Empire: Local Self Government, Art and Architecture. 65-82 3. Features of Indian Village System, Society, Economy, Art and 83-99 learning in South India. Unit-III. Indian Society in early Medieval Age. 1. Social stratification: Proliferation of castes, Status of women, 100-112 Matrilineal System, Aryanisation of hinterland region. 2. Religion-Bhakti Movements, Saivism, Vaishnavism, Tantricism, 113-128 Islam. 3. Development of Art and Architecture: Evolution of Temple Architecture- Major regional Schools, Sculpture, Bronzes and 129-145 Paintings. Unit-IV. Indian Economy in early medieval age. 1. General review of the economic life: Agrarian and Urban 146-161 Economy. 2. Indian Feudalism: Characteristic, Nature and features. 162-180 Significance. 3. Trade and commerce- Maritime Activities, Spread of Indian 181-199 Culture abroad, Cultural Interaction. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT It is pleasure to be able to complete this compilation work. containing various aspects of Ancient Indian History. This material is prepared with an objective to familiarize the students of M.A History, DDCE Utkal University on the various aspcets of India’s ancient past. -

Khajuraho Group of Temples

Khajuraho group of temples March 27, 2021 In news Recently, the Union Minister of Tourism attended the session on ‘Making Khajuraho–as Iconic Tourist Destination’ in Khajuraho About Khajuraho group of temples Location: Khajuraho is a city of Group of Monuments is a group of Hindu temples and Jain temples in Chhatarpur district, Madhya Pradesh Khajuraho is known for its wonderful and exquisite architectural temples. The temples are famous for their nagara-style architectural symbolism and their erotic sculptures. Time period & Dynasty: Most Khajuraho temples were built between 885 AD and 1050 AD by the Chandela dynasty Each and every temple architectural styles in Khajuraho defines wrestling, royalty, meditation, spiritual teachings, kinship etc and many arts. Major significant attraction of these temples especially Kandariya temple is erotic sculptures and art Style of architecture: The group of temples of Khajuraho testifies to the culmination of northern Indian temple art and architecture of the Chandella dynasty and they are of high quality of Nagara-style temple architecture. The Khajuraho Group of Monuments demonstrates in layout and physical form, the pinnacle of temple architectural development in northern India. Built in sandstone, each temple is elevated from its environs by a highly ornate terraced platform, or jagati, on which stands the body, or jangha, whose sanctum is topped by a tower, or shikhara, of a type unique to Nagara, where the verticality of the principal spire atop the sanctum is accentuated by a series of miniature spires flanking it, each symbolizing Mount Kailasa, the abode of the Gods. Plan of temples The plan of the temples shows the spatial hierarchy of axially aligned interconnected spaces.