He Who Does Not Howl.Pmd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagner Intoxication

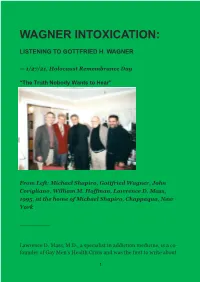

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

Wagner in Context

Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music Upcoming Events and Performances Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music Wednesday, October 16, 8pm Boston University Center for Early Music Studies: Blue Heron Marsh Chapel Friday, October 18, 8pm Boston University All-Campus Orchestra Mark Miller, conductor CFA Concert Hall Saturday, October 19, 8pm Choral Ensembles Concert Marsh Chapel Tuesday, October 22, 8pm Dr. Gottfried Wagner Boston University Concert Orchestra Neal Hampton, conductor Tsai Performance Center Wagner in Context “Opera and politics: Richard Wagner (1813-2013) – a minefield” Boston University Theatre, 264 Huntington Avenue Marsh Chapel, 735 Commonwealth Avenue Tsai Performance Center, 685 Commonwealth Avenue CFA Concert Hall, 855 Commonwealth Avenue Tuesday, October 15, 2013, 7pm CFA Concert Hall bu.edu/cfa Text BUARTS to 22828 • twitter.com/BUArts • facebook.com/BUARTS Dr. Gottfried Wagner Boston University College of Fine Arts School of Music STRINGS Mike Roylance tuba Robinson Pyle CONDUCTING Born in 1947 in Bayreuth, Dr. Gottfried Wagner studied musicology, Steven Ansell viola * Eric Ruske horn * natural trumpet David Hoose * philosophy and German philology in Germany and Austria and wrote Edwin Barker double bass * Robert Sheena english horn Marc Schachman Ann Howard Jones * Cathy Basrak viola Thomas Siders trumpet baroque oboe Scott Allen Jarrett his dissertation on Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht at the University of Lynn Chang violin Ethan Sloane clarinet * Aaron Sheehan HPvoice Kevin Leong (SI) Wesley Collins viola Jason Snider horn Jane Starkman David Martins Vienna, which was published later as book in Germany, Italy and Daniel Doña pedagogy, chamber* Samuel Solomon baroque violin, viola Jameson Marvin (SII) Jules Eskin cello percussion Peter Sykes harpsichord * Scott Metcalfe Japan. -

Great-Grandson of Richard Wagner to Speak on Anti-Semitism in Germany

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Social Justice: Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion Special Collections 10-17-2002 Great-Grandson of Richard Wagner to Speak on Anti-Semitism in Germany Joe Carr University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/social_justice Part of the European History Commons, Holocaust and Genocide Studies Commons, and the Race and Ethnicity Commons Repository Citation Carr, Joe, "Great-Grandson of Richard Wagner to Speak on Anti-Semitism in Germany" (2002). Social Justice: Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion. 290. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/social_justice/290 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Social Justice: Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Wayback Machine - https://web.archive.org/web/20031105064504/http://www.umaine.edu:80/News/Arch… University of Maine News Great-Grandson of Richard Wagner to Speak on Anti- Semitism in Germany Oct. 17, 2002 Media contact: Joe Carr at (207) 581-3571 ORONO -- The great-grandson of composer Richard Wagner will give a lecture, "From Wagner to Hitler: Anti-Semitism and Culture in Germany," on Nov. 4 at the University of Maine. Gottfried Wagner, co-founder of the Post-Holocaust Generations Dialogue Group, will speak at 7 p.m. in Devino Auditorium, Corbett Business Building. His talk is sponsored by UMaine's School of Performing Arts, and the Departments of History and Modern Languages and Classics. A reception sponsored by the Holocaust Human Rights Center of Maine will follow the lecture. -

Cultural Cooperation in Europe What Role for Foundations?

Network of European Foundations for Innovative Cooperation Cultural Cooperation in Europe what role for Foundations? Research report by Fondazione Fitzcarraldo FONDAZIONE FITZCARRALDO Research group: Ugo Bacchella Laura Cherchi Ilda Curti Luca Dal Pozzolo Christopher Gordon Maddalena Rusconi Our special thanks to the experts Raj Isar and Rupert Graf Strachwitz for their commitment to the project and their thoughtful and critical contributions that enriched the research. Furthermore our special thanks go to the NEF Steering Committee: Raymond Georis (NEF), Dan Brändstrom (Stiftelsen Riksbankens Jubileumsfond), Francis Charhon (Fondation de France), Dario Disegni (Compagnia di San Paolo), Gottfried Wagner (European Cultural Foundation). Cultural cooperation in Europe: What role for Foundations? Final Report TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 PART I: A picture of the state-of-the-art ------------------------------------------------------------------ 6 1. The context of reference ----------------------------------------------------------------------------- 7 1.1. Sectors of intervention --------------------------------------------------------------------------- 9 1.2. Features of the working approach: cooperation tools -------------------------------------- 10 1.3. Territorial scope ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 11 1.4. Obstacles to international cooperation ------------------------------------------------------- -

I Am Writing to Bring to Your Attention an Important

March 7, 2016 To Whom It May Concern: I am writing to bring to your attention an important and timely book on the man and the myth of Richard Wagner, “Thou Shalt Have no Other Gods Before Me.” There has yet to be a book in English that so directly and clearly confronts the dissonance between Wagner as an icon of inhumanity unique among artists, yet who is the celebrated center of an international cult still flourishing today. This explosive book therefore portends a seismic shift in our understanding of Wagner and unmasks him as the anti-Gandhi and anti-Mandela for out time. Tailored to the needs and interests of as broad as possible a reading public, this book has been produced by none other than Wagner’s own great-grandson, Gottfried. Yet this is no personal exposé or family-tell- all; Gottfried already accomplished that task years ago, and to great acclaim. His first book, “Twilight of the Wagners,” was an international bestseller that proved the great interest and viability of such a subject and audience in the international arena. This second book is instead not a memoir but a serious, thoroughly researched work of public history that chronicles Wagner as an epigone of all the worst ills of modernity. He has now authorized me as a trained historian to guide this project to translation and expansion for the English-speaking world. Gottfried Wagner’s “Thou Shalt Have no Other Gods Before Me,” has already been published to strong press and public reception by the Ullstein Verlag in 2013. -

Crying 'Wolf'? a Review Essay on Recent Wagner Literature

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 2-2001 Crying ‘Wolf’? A Review Essay on Recent Wagner Literature David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the European History Commons Author Manuscript This is a pre-publication author manuscript of the final, published article. Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. Crying ‘Wolf’? A Review Essay on Recent Wagner Literature. German Studies Review, , : 145-158, 2001. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © German Studies Association 2001 Crying “Wolf”? A Review Essay on Recent Wagner Literature David B. Dennis German Studies Review Joachim Köhler. Wagner’s Hitler: The Prophet and his Disciple. Translated by Ronald Taylor. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2000. Pp. 378. Cloth $29.95. Stephen McClatchie. Analyzing Wagner’s Operas: Alfred Lorenz and German Nationalist Ideology. Eastman Studies in Music. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 1998. Pp. xiii, 262. Cloth $95.00. Lydia Goehr. The Quest for Voice: On Music, Politics, and the Limits of Philosophy: The 1997 Ernest Bloch Lectures. Oxford, U.K.; New York: Clarendon Press; Oxford University Press, 1998. Pp. x, 237. -

Creative Sector” – an Engine for Diversity, Growth and Jobs in Europe

THE “CREATIVE SECTOR” – AN ENGINE FOR DIVERSITY, GROWTH AND JOBS IN EUROPE An overview of research findings and debates prepared for the European Cultural Foundation By Andreas Wiesand in co-operation with Michael Söndermann1 September 2005 1 Andreas Johannes Wiesand is Executive Director of the European Institute of Comparative Cultural Research (ERICarts) as well as head of the 35-year old German Zentrum für Kulturforschung (ZfKf). Michael Söndermann is President of the Task Force for Cultural Statistics (ARKStat); he contributed a compilation of statistics for the “Creative Sector”. Thanks to Gottfried Wagner (European Cultural Foundation) and Danielle Cliche (ERICarts -Institute) for inspiring the paper with questions and ideas. 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The paper asks, how the arts and the culture / media industries could contribute to the general goal “Growth and Employment” of the renewed EU Community Lisbon Programme (July 2005). It defines the scope of a “Creative Sector” from a European perspective and discusses recent re- search findings and debates, in addition to drawing some conclusions for further action. In contrast to the current debate among economists about a “creative class” (R. Florida), a pro- posed European definition of the Creative Sector comprises the arts, media and heritage with all connected professional activities in public or private organisations, including in neighbouring fields such as design, architecture or the production of music instruments. It points to linkages be- tween the different fields and identifies occupational or “creative clusters” as well as “complemen- tary relationships” between public institutions and private companies or non-profit bodies. The paper summarizes main empirical findings, including: • The combined workforce of the Creative Sector in 31 European countries (EU, 2 applicant countries and EFTA) can be estimated to be higher than 4.7 million people (ca. -

Curriculum Vitae

1 CURRICULUM VITAE Marc A. Weiner Autumn 2010 Department of Germanic Studies Ballantine Hall 644 1020 E. Kirkwood Ave. 1111 Azalea Lane Bloomington, IN 47405-7103 Bloomington, IN 47401 (812) 855-2033 (Direct Dial) 855-7947 (Dept. Main Office) FAX: 812 855-8927 E-Mail: [email protected] POSITIONS Indiana University: 1996- Professor of Germanic Studies & Adjunct Professor of Comparative Literature; Adjunct Professor of Communication and Culture; Adjunct Professor of Cultural Studies 1997-2004 Director, Institute of German Studies 1995-97 Editor, The German Quarterly 1992-96 Associate Professor of Germanic Studies 1985-92 Assistant Professor of Germanic Studies Harvard University: 1987-88 Andrew W. Mellon Faculty Fellow German Department/Center for Cultural and Literary Studies EDUCATION Stanford University Ph.D. in German Studies, June 1984 M.A. in German Studies, June 1979 University of Massachusetts, Amherst B.A. (Major: German Studies; Minor: Music History) summa cum laude, May 1978 2 GRANTS, FELLOWSHIPS, HONORS, and AWARDS (selected) 2008 Graduate Student Teaching Award, Dept. of Germanic Studies, IUB 2006 Indiana University Short-Term Faculty Exchange to Hamburg 2004- Elected to the “PEN-Club für deutschsprachige Autoren im Ausland.” May 2004. 2000-2001 Alexander von Humboldt Foundation Research Fellowships, Bonn (February 2000—August 2001) 1998-2001 Appointed Member of the Publication of the Modern Language Association Advisory Committee 1997-2001 Finkelstein Fellow, Indiana University (one of ten such Fellows—rotating endowed Chairs--selected -

Musicreborn Outside Cover Black PANTONE 192 CV Musicreborn ARC: Artists of the Royal Conservatory Music Reborn: Composers of the Holocaust

311-152 MusicReborn Outside Cover Black PANTONE 192 CV MusicReborn ARC: Artists of The Royal Conservatory Music Reborn: Composers of the Holocaust THE ROYAL CONSERVATORY OF MUSIC 273 BLOOR STREET WEST TORONTO, ON CANADA M5S1W2 TEL 416.408.2824 www.rcmusic.ca PRINTED IN CANADA 311-152 MusicReborn Inside Cover Black PANTONE 192 CV Acknowledgments Prof. David Bloch, Tel Aviv, Terezín Music ARC is indebted Memorial Project Czech Music Fund, Prague to the following Michael Doleschell, Guelph individuals Shaun Elder, RCM, Toronto Henry Ingram, Dean Artists, Toronto and organizations Joza Karas, Hartford, Connecticut Robert Kolben, Munich who helped Connie McDonald, Royal Ontario Museum Arlene Perly Rae, Toronto assemble Muzikgroep Netherlands, Amsterdam Paul Schoenfield, Cleveland, Ohio Music Reborn Kate Sinclair, RCM, Toronto Mary Siklos, UJA Federation, Toronto Per Skans, Uppsala Evan Thompson, Royal Ontario Museum Dr. Gottfried Wagner, Milan Ulrike zur Nieden, Peer Music Classical, Hamburg The score of the Weinberg Piano Quintet has long been out of print and ARC is indebted to Peer Music who generously made the parts available in advance of their forthcoming Weinberg republications. Special thanks to Bret Werb (U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C.) for his knowledgeable guidance and generous assistance. This festival made possible by the generous support of: Leslie & Anna Dan and Family, Vivian & David Campbell, Mark Feldman & Alix Hoy, Florence Minz & Gordon Kirke, Dorothy & Irving Shoichet Presented in association with: 1944 -

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Vol

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Vol. 2 No. 1 Spring 1984 Foundation Initiates Grants Program Early Weill Manuscripts Discovered The Board of Trustees is pleased to contain a detailed description of the On November 5, 1983, during the last announce the establishment of the project, a current resume of individuals day of the Kurt Weill Conference at Foundation's first grants program, de involved and/or a profile of purposes, Yale University, Foundation President signed to further its goals of promoting activities and past achievements of or Kirn Kowalke announced the discovery public understanding and appreciation ganizations, and an itemized statement of 14 early Weill manuscripts dating of the musical works of Kurt Weill. In of how the amom1t requested would be from 1916-19, with one fragment com 1984, the Foundation is accepting pro utilized. After applications have been posed possibly as early as 1911. Of the posals in five major categories related reviewed by the Foundation's staff, ad 14 manuscripts, 11 are of compositions to the perpetuation of Weill' s artistic ditional supporting materials may be W1known to have existed, or presumed legacy: requested for consideration by the Ad lost. Dr. Hanne Weill Holesovsky, l. Research Grants visory Panel on Grant Evaluations, daughter of Weill's brother Hanns, in 2. Publicatwn Assistance which will make recommendations to formed Lys Syrnonette in November, 3. Performance and Production Grants the Board of Trustees. Grants will be 1981, that her mother, Rita Weill (now 4. Dissertatwn Fellowships awarded on an objective and non-dis deceased), might possess a number of 5. Travel Grants criminatory basis. -

Bayreuth After Wagner: Psychosocial Perspectives on Cosima Wagner, Winifred Wagner, and Houston Stewart Chamberlain

Bayreuth after Wagner: Psychosocial Perspectives on Cosima Wagner, Winifred Wagner, and Houston Stewart Chamberlain Eric Doughney Submitted in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy International Centre for Music Studies Newcastle University January 2018 Abstract The Wagner institution at Bayreuth, after Wagner, was shaped as much by the psychologies of those to whom the composer’s legacy was entrusted as it was by purely historical and political events. Entwining musicological, philosophical, sociological, and psychoanalytic discourses, this revisionist and hermeneutic history of Bayreuth focuses on three individuals whose lives were acutely intertwined with the cultural and political evolution of the establishment: Cosima Wagner, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, and Winifred Wagner. Their personal and social paths were embedded in larger political and cultural changes, especially German nationalism, yet despite the intensity of their nationalist affinities none was indigenously German and in childhood each lacked those influences now considered essential for effective individuation. Following an initial discussion on Wagner, character studies of each applying, particularly, Jungian and Eriksonian theory explore the extent to which those absences and related factors informed not only their personal development but also the dynamics of their respective relationships with Wagner from which our perception of the composer and Bayreuth as an institution derives. i ii For my family iii iv Acknowledgements Considering the number of years -

Abendprogramm Bwv 182:Layout 1.Qxd

HIMMELS KöNIG, SEI WILL KOMMEN freitag, 30. märz 07 trogen (ar) freitag, 30. märz 2007, trogen (ar) johann sebastian bach (1685–1750) “himmelskönig, sei willkommen” Kantate BWV 182 zu Palmarum für Alt, Tenor und Bass Vokalensemble, Flauto dolce, Streicher und Continuo 17.00–17.45 uhr, kronensaal, trogen Workshop I zur Einführung in das Werk mit Rudolf Lutz und Karl Graf 18.00–18.45 uhr, kronensaal, trogen Workshop II für vorangemeldete Teilnehmer vor bzw. nach den workshops Kleiner Imbiss und Getränke in der Gaststube der Krone Trogen eintritt: fr. 40.– 19.00 uhr, evangelische kirche, trogen Erste Aufführung der Kantate Reflexion über den Kantatentext: Gottfried Wagner Zweite Aufführung der Kantate eintritt frei–kollekte ausführende solisten Claude Eichenberger, Alt; Bernhard Berchtold, Tenor; Raphael Jud, Bass vokalensemble der schola seconda pratica Sopran: Susanne Frei, Guro Hjemli, Noëmi Tran-Rediger Alt: Jan Börner, Antonia Frey, Olivia Heiniger Tenor: Marcel Fässler, Manuel Gerber, Walter Siegel Bass: Fabrice Hayoz, Philippe Rayot, William Wood schola seconda pratica Violine: Renate Steinmann Viola: Susanna Hefti, Céline Portat Violoncello: Maya Amrein Violone: Constantin Bradatan Blockflöte: Armelle Plantier Orgel: David Blunden leitung Rudolf Lutz reflexion Gottfried Wagner wurde in Bayreuth geboren und studierte Musikwissenschaft, Philosophie und Germa - nis tik in Deutschland und Österreich. Er promovierte zum Dr. phil. an der Universität Wien 1977 über «Das musikalische Zeittheater von Kurt Weill und Bertolt Brecht». Gottfried Wagner ist international als freibe- ruflicher Autor und Regisseur tätig mit Interessen- schwerpunkten auf deutscher Kultur und Politik des 19. und 20. Jahrhunderts, Antisemitismus, Weill, Ull- mann, Wagner und Liszt. Er ist Mitglied des Pen Clubs Liechtenstein.