Crying 'Wolf'? a Review Essay on Recent Wagner Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wagner Intoxication

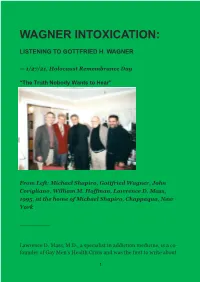

WAGNER INTOXICATION: LISTENING TO GOTTFRIED H. WAGNER — 1/27/21, Holocaust Remembrance Day “The Truth Nobody Wants to Hear” From Left: Michael Shapiro, Gottfried Wagner, John Corigliano, William M. Hoffman, Lawrence D. Mass, 1995, at the home of Michael Shapiro, Chappaqua, New York _________ Lawrence D. Mass, M.D., a specialist in addiction medicine, is a co- founder of Gay Men’s Health Crisis and was the first to write about 1 AIDS for the press. He is the author of We Must Love One Another or Die: The Life and Legacies of Larry Kramer. He is completing On The Future of Wagnerism, a sequel to his memoir, Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite. For additional biographical information on Lawrence D. Mass, please see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lawrence_D._Mass Larry Mass: For Gottfried Wagner, my work on Wagner, art and addiction struck an immediate chord of recognition. I was trying to describe what Gottfried has long referred to as “Wagner intoxication.” In fact, he thought this would make a good title for my book. The subtitle he suggested was taken from the title of his Foreword to my Confessions of a Jewish Wagnerite: “Redemption from Wagner the redeemer: some introductory thoughts on Wagner’s anti- semitism.” The meaning of this phrase, “redemption from the redeemer,” taken from Nietzsche, is discussed in the interview with Gottfried that follows these reflections. Like me, Gottfried sees the world of Wagner appreciation as deeply affected by a cultish devotion that from its inception was cradling history’s most irrational and extremist mass-psychological movement. -

From Page to Stage: Wagner As Regisseur

Wagner Ia 5/27/09 3:55 PM Page 3 Copyrighted Material From Page to Stage: Wagner as Regisseur KATHERINE SYER Nowadays we tend to think of Richard Wagner as an opera composer whose ambitions and versatility extended beyond those of most musicians. From the beginning of his career he assumed the role of his own librettist, and he gradually expanded his sphere of involvement to include virtually all aspects of bringing an opera to the stage. If we focus our attention on the detailed dramatic scenarios he created as the bases for his stage works, we might well consider Wagner as a librettist whose ambitions extended rather unusually to the area of composition. In this light, Wagner could be considered alongside other theater poets who paid close attention to pro- duction matters, and often musical issues as well.1 The work of one such figure, Eugène Scribe, formed the foundation of grand opera as it flour- ished in Paris in the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Wagner arrived in this operatic epicenter in the fall of 1839 with work on his grand opera Rienzi already under way, but his prospects at the Opéra soon waned. The following spring, Wagner sent Scribe a dramatic scenario for a shorter work hoping that the efforts of this famous librettist would help pave his way to success. Scribe did not oblige. Wagner eventually sold the scenario to the Opéra, but not before transforming it into a markedly imaginative libretto for his own use.2 Wagner’s experience of operatic stage produc- tion in Paris is reflected in many aspects of the libretto of Der fliegende Holländer, the beginning of an artistic vision that would draw him increas- ingly deeper into the world of stage direction and production. -

Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20Th Century Composers

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons History: Faculty Publications and Other Works Faculty Publications 1-8-2010 War on Modern Music and Music in Modern War: Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20th Century Composers David B. Dennis Loyola University Chicago, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/history_facpubs Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dennis, David B.. War on Modern Music and Music in Modern War: Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20th Century Composers. "Music, War, and Commemoration” Panel of the American Historical Association Conference in San Diego, CA, 2010, , : , 2010. Retrieved from Loyola eCommons, History: Faculty Publications and Other Works, This Conference Proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History: Faculty Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. © 2010 David Dennis. WAR ON MODERN MUSIC AND MUSIC IN MODERN WAR: VÖLKISCHER BEOBACHTER RECEPTION OF 20th CENTURY COMPOSERS A paper for the “Music, War, and Commemoration” Panel of the American Historical Association Conference in San Diego, CA January 8, 2009 David B. Dennis Department of History Loyola University Chicago Recent scholarship on Nazi music policy pays little attention to the main party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, or comparable publications for the gen- eral public. Most work concentrates on publications Nazis targeted at expert audiences, in this case music journals. But to think our histories of Nazi music politics are complete without comprehensive analysis of the party daily is prema- ture. -

Chytry POEM'e'

MANAGER AS ARTIST Dégot ‘APHRODISIAN BLISS’ Chytry POEM‘E’: MANAGING ‘ENGAGEMENT’ Guimarães-Costa & Pina e Cunha PERIPHERAL AWARENESS Chia & Holt FUNKY proJECts Garcia and Pérez AesthetiCS OF Emptiness Biehl POETRY PLAY Darmer, Grisoni, James & Rossi Bouchrara WORKPLACE proJECts James DVD DRAMA Taylor AVANT GARDE ORGANIZATION Vickery Aesthesis//Create International journal of art and aesthetics in management and organizational life and organizational International journal of art and aesthetics in management Volume 1//TWO: 2007 AESTHESIS: International Journal of Art and Aesthetics in Management and Organizational Life EditorS Ian W. King, Essex Management Centre, University of Essex, Colchester, UK Jonathan Vickery, Centre for Cultural Policy Studies, University of Warwick, Coventry, UK Ceri Watkins, Essex Management Centre, University of Essex, Colchester, UK Editorial coordiNator Jane Malabar [email protected] Editorial AdviSORY Board Dawn Ades, University of Essex, UK Daved Barry, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Portugual Jo Caust, University of South Australia, Editor, Asia Pacific Journal of Arts and Cultural Management Pierre Guillet de Monthoux, University of Stockholm, Sweden Laurie Heizler, Wright Hassallthe LLP, Leamington Spa, UK Stephen Linstead, University of York, UK Nick Nissley, The Banff Centre, Canada Antonio Strati, University of Trento and University of Siena, Italy Steve Taylor, Worcester PolytechnicAes Institute, USA thesis This journal is published by THE AESTHESIS ProjEct: The Aesthesis Project was founded in January 2007 and is a research project investigatingproject art and aesthetics in management and organizational contexts. The project has its roots in the first Art of Management and Organization Conference in London in 2002, with successive conferences held in Paris and Krakow. From those events emerged an international network of academics, writers, artists, consultants and managers, all involved in exploring and experimenting with art in the context of management and organizational research. -

Kevin John Crichton Phd Thesis

'PREPARING FOR GOVERNMENT?' : WILHELM FRICK AS THURINGIA'S NAZI MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR AND OF EDUCATION, 23 JANUARY 1930 - 1 APRIL 1931 Kevin John Crichton A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2002 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13816 This item is protected by original copyright “Preparing for Government?” Wilhelm Frick as Thuringia’s Nazi Minister of the Interior and of Education, 23 January 1930 - 1 April 1931 Submitted. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, 2001 by Kevin John Crichton BA(Wales), MA (Lancaster) Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP) Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) (c) 2001 KJ. Crichton ProQuest Number: 10170694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10170694 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author’. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 CONTENTS Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements Abbreviations Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Background 33 Chapter Three: Frick as Interior Minister I 85 Chapter Four: Frick as Interior Ministie II 124 Chapter Five: Frickas Education Miannsti^r' 200 Chapter Six: Frick a.s Coalition Minister 268 Chapter Seven: Conclusion 317 Appendix Bibliography 332. -

Florida State University Libraries

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2009 Gustav Mahler, Alfred Roller, and the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk: Tristan and Affinities Between the Arts at the Vienna Court Opera Stephen Carlton Thursby Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC GUSTAV MAHLER, ALFRED ROLLER, AND THE WAGNERIAN GESAMTKUNSTWERK: TRISTAN AND AFFINITIES BETWEEN THE ARTS AT THE VIENNA COURT OPERA By STEPHEN CARLTON THURSBY A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2009 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Stephen Carlton Thursby defended on April 3, 2009. _______________________________ Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Dissertation _______________________________ Lauren Weingarden Outside Committee Member _______________________________ Douglass Seaton Committee Member Approved: ___________________________________ Douglass Seaton, Chair, Musicology ___________________________________ Don Gibson, Dean, College of Music The Graduate School has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To my wonderful wife Joanna, for whose patience and love I am eternally grateful. In memory of my grandfather, James C. Thursby (1926-2008). iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the generous assistance and support of numerous people. My thanks go to the staff of the Austrian Theater Museum and Austrian National Library-Music Division, especially to Dr. Vana Greisenegger, curator of the visual materials in the Alfred Roller Archive of the Austrian Theater Museum. I would also like to thank the musicology faculty of the Florida State University College of Music for awarding me the Curtis Mayes Scholar Award, which funded my dissertation research in Vienna over two consecutive summers (2007- 2008). -

Wagmer Neypmd Good and Evil

36167_u01.qxd 1/7/08 4:06 PM Page 3 1. Wagner Lives Issues in Autobiography Wagner’s biography has been researched to within an inch of its life. It has been dissected, drenched with no end of detail, eroticized, vilified, heroi- cized, and several times filmed.1 Its foundations are the collected writings, which in the first instance Wagner edited himself in the spirit of an autobi- ographical enterprise;2 a separate and lengthy autobiography, Mein Leben (My life), dictated to his mistress and later second wife, Cosima, daughter of Franz Liszt;3 notebooks and diaries;4 photographs and portraits;5 an un- usually large number of letters;6 mounds of anecdotal gossip; and no end of documentation on the way he lived and how his contemporaries saw him.7 In this sense, he is almost the exact antithesis of Shakespeare, whose life, or at least what is safely known about it in terms of verifiable “facts,” can be told in a relatively short space. I have summarized the history of Wagner biography elsewhere.8 Here I want to look at Wagner’s own portrayals of his life, some issues they raise, the philosophical spirit in which I believe they were attempted, and their effect on the generation that came immediately after him. Biographers of Shakespeare have had to resort to imaginative recon- structions and not infrequently to knowingly forged documents that have accorded their subject more lives than a cat.9 In stark contrast, there appears to be only one life for Wagner, which he did his best to determine in large part himself. -

Richard Wagner RIENZI Der Letzte Der Tribunen

Richard Wagner RIENZI der letzte der Tribunen Grande opera tragica in cinque atti Libretto di Richard Wagner Dal romanzo “Rienzi, the Last of the Roman Tribunes” di Edward Bulwer-Lytton Traduzione italiana di Guido Manacorda Prima rappresentazione Dresda, Königliches Hoftheater 20 ottobre 1842 PERSONAGGI COLA DI RIENZI tribuno romano tenore IRENE, sua sorella soprano STEFANO COLONNA capo della famiglia Colonna basso ADRIANO suo figlio mezzosoprano PAOLO ORSINI capo della famiglia Orsini basso RAIMONDO legato pontificio basso BARONCELLI tenore CECCO DEL VECCHIO basso UN MESSO DI PACE soprano Cittadini romani, inviati delle città lombarde, nobili romani, cittadini di Roma, messi dipace, ecclesiastici di ogni ordine, guardie romane. Wagner: Rienzi – atto primo ATTO PRIMO [N° 1 - Introduzione] Scena I° Una via di Roma. Sullo sfondo la chiesa del Laterano; sul davanti a destra la casa di Rienzi. È notte (Orsini con 6-8 suoi partigiani davanti alla casa di Rienzi) ORSINI ORSINI È qui, è qui! Su, svelti amici. Hier ist’s, hier ist’s! Frisch auf, ihr Freunde. appoggioate la scala alla finestra! Zum Fenster legt die Leiter ein! (Due nobili salgono la scala ed entrano per una finestra aperta nella casa di Rienzi) La fanciulla più bella di Roma sarà mia, Das schönste Mädchen Roms sei mein; penso che sarete d’accordo con me. ihr sollt mich loben, ich versteh’s. (I due nobili portano Irene fuori dalla casa) IRENE IRENE Aiuto! Aiuto! O Dio! Zu Hilfe! Zu Hilfe! O Gott! GLI O RSINIANI DIE ORSINI Ah, che divertente rapimento Ha, welche lustige Entführung dalla casa del plebeo! aus des Plebejers Haus! IRENE IRENE Barbari! Osate un tale oltraggio? Barbaren! Wagt ihr solche Schmach? GLI O RSINIANI DIE ORSINI Non opporre resistenza, bella fanciulla, Nur nicht gesperrt, du hübsches Kind, Vedi: sono troppi gli aspiranti! du siehst, der Freier sind sehr viel! ORSINI ORSINI Vieni, pazzerella, non essere cattiva. -

Gottfried Semper. Ein Bild Seines Lebens Und Wirkens Mit Benutzun

GOTTFRIED SEMPER EIN BILD SEINES LEBENS UND WIRKENS MIT BENUTZUNG DER FAMILIENPAPIERE VON HANS SEMPER PROFESSOR DER KUNSTGESCHICHTE IN INNSBRUCK. BERLIN VERLAG VON S. CALVARY & CO. MDCCCLXXX. GOTTFRIED SEMPER EIN BILD SEINES LEBENS UND WIRKENS MIT BENUTZUNG DER FAMILIENPAPIERE HANS SEMPER PROFESSOR DER KUNSTGESCHICHTE IN INNSBRUCK. BERLIN VERLAG VON S. CALVARY & CO. MDCCCLXXX. (jTottfried Semper wurde am 29. November 1803 zu Hamburg als der zweitjüngste Sohn eines Wollen -Fabrikanten geboren und in der evangelisch -reformirten Kirche zu Altona getauft. Er erhielt eine sorg- fältige Erziehung und insbesondere übte der willensstarke Charakter sei- ner Mutter einen grossen Einfluss auf seine Entwickelung aus. — Trotz der strengen Zucht, unter der er heranwuchs, verkündigten doch schon mehrere Vorfälle seiner Kindheit, mit welcher unerschrockenen Energie er dereinst seinen Ueberzeugungen und seinem Streben Ausdruck und Gel- tung verschaffen würde. Er machte die Gymnasialstudien, die er glän- zend absolvirte, am Johanneum seiner Vaterstadt und legte dort den Grund zu seiner Liebe zum Alterthum, sowie zu seiner umfassenden Kenntniss der griechischen und römischen Literatur. Wie lebendig er schon in dieser Zeit den Geist der alten Schrift- steller in sich aufnahm, wie er aber trotz dieser Vorliebe für das klas- sische Alterthum dennoch von den Qualen nicht verschont blieb, die so mancher Jüngling empfindet, an den die Wahl des Lebensberufes heran- tritt, das zeigt eine Stelle aus einem Briefe, den er viele Jahre nachher an Regierungsrath Hagenbuch -

Musicians Who Kept It Quiet During World War II

Musicians who kept it quiet during World War II • Shirley Apthorp From: The Australian November 19, 2011 12:00AM The Spivakovsky-Kurtz trio, from left, Tossy and Jascha Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz. Source: Supplied German musicologist and music critic Albrecht Dumling. Picture: Ana Pinto Source: Supplied THE invitation to bomb Berlin caught Albrecht Dumling by surprise. The German musicologist was not being collared by militant extremists in a dark pub. He was visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. There is an exhibit of a Royal Air Force bomber plane with an interactive button to simulate bombing Berlin. "It's like an adventure toy," Dumling recalls. "It felt very strange to be prompted to drop bombs on Berlin. I didn't." Instead, he wrote a book. Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia has just been published by the Bohlau Verlag in Germany. It contains many shocking revelations about a largely forgotten side of Australia's cultural past. Questioning the way history is presented is one of Dumling's chief preoccupations. He was in Canberra to sift through the National Archives, looking into what really happened to Jewish musicians whose flight from Nazi terror brought them to Australia. Today, it is tempting to imagine Australia as a safe haven, where the unjustly persecuted could begin again. The reality was different. Australia was not eager to accept Jewish immigrants. At the Evian Conference of 1938, Australia's trade and customs minister Thomas White, pleading against large-scale Jewish immigration, declared that "as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one". -

Richard Wagner in Der Schweiz (1849-1858) Als Künstler Und Mensch Zu Den Prägends- Die Von Wagners Schaffen Am Bühnenwerk Ten Seines Lebens Gehörten

Richard Wagner in der Schweiz (1849-1858) als Künstler und Mensch zu den prägends- die von Wagners Schaffen am Bühnenwerk ten seines Lebens gehörten. Zürich wurde „Tristan und Isolde – Handlung in drei Auf- zu einem „Versuchsfeld“, wo vorhandene zügen“, geprägt waren, welche er erstmalig in Ideen ausreiften, neue entstanden und um- einem Brief an Franz Liszt 1854 erwähnte. gesetzt werden konnten. Wagner dirigierte Am 17. August 1858, noch vor Minna Wag- und schrieb in rascher Folge kunsttheoreti- ner, verlässt der Komponist Zürich fluchtar- sche Schriften, Dramentexte und Komposi- tig und gleichsam fragmentarisch, denn so- tionen. Im Mai 1853 fanden hier die ersten wohl der „Ring“ als auch der „Tristan“ er- Wagner-Festspiele überhaupt statt. lebten ihre Vollendung anderswo. Aber von Die Ausstellung stand unter der Schirm- Zürich nahm Richard Wagner noch die Idee herrschaft von Dr. Peter Stüber, Honorar- zum Bühnenwerk „Parsifal“ mit. konsul der Bundesrepublik Deutschland in Selten gezeigte Handschriften, rare No- Zürich, und wurde im Rahmen der Zürcher tendrucke, Alltagsgegenstände wie Wagners Festspiele 2008 eröffnet. Gleich zu Beginn Stoffmuster, sein Schreibpult oder sein gol- sieht der Besucher hautnah den Grund für dener Federhalter, sowie Bilder und Musik- Wagners Flucht nach Zürich uns Exil, die instrumente lassen den Besucher in die Zeit Dresdner Holzbarrikaden des gescheiterten des großen Künstlers und Komponisten ein- Aufstandes im Mai 1849. Klaus Dröge, der tauchen, wobei die thematisch und optisch in der Begleitpublikation eine interessan- perfekte Darstellung der Ausstellungsgegen- ten Aufsatz unter dem Titel „Richard Wag- stände beeindruckte. Einige, die in direktem ners Schaffen in Zürich: Ein Überblick“ ge- Zusammenhang mit Wagners Zeit in Zürich schrieben hat, unterteilt die Zürcher Jah- stehen, sollen kurz hervorgehoben werden. -

Richard Wagner on the Practice and Teaching of Singing

Richard Wagner on the Practice and Teaching of Singing By Peter Bassett [A paper presented to the 8th International Congress of Voice Teachers on 13 July 2013.] Weber and Beethoven were still alive when Wagner was a teenager, and their long shadows, together with those of Mozart and Marschner fell on all his early projects. His first completed opera Die Feen, composed in 1833 when he was just twenty years old, was never performed in his lifetime but, even if it had been, it wouldn’t have sounded as good as it does in the best recorded versions we know today. The type of singing familiar to Wagner was far from ideal, and many German singers of his era were poorly trained and had unsophisticated techniques. His sternest critic, Eduard Hanslick had something to say on the difference between German and Italian singers at that time: ‘With the Italians’ he said, ‘great certainty and evenness throughout the role; with the Germans an unequal alternation of brilliant and mediocre moments, which seems partly accidental.’ Wagner had to entrust his major roles to inadequately trained singers in many cases, which must have been challenging to say the least. He worked hard to improve matters, pouring much time and energy into the preparation of performances. ‘I do not care in the slightest’ he once said, ‘whether my works are performed. What I do care about is that they are performed as I intended them to be. Anyone who cannot, or will not, do so, had better leave them alone.’ David Breckbill has written that ‘The differences between the singing which Wagner knew and that which we hear today are considerable.