Voelkischer Beobachter Reception of 20Th Century Composers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hold on to Love

Karen Drucker Hold On To Love 1. KEEP THAT PASSION BURNING words & music: Frank Macchia & Karen Drucker 2. ON MY WAY words: Debra Turner & Karen Drucker music: Karen Drucker 3. LISTEN TO THE CHILDREN words: Roberta Rigney & Karen Drucker music: Karen Drucker 4. I BELIEVE IN FIREFLIES words & music: Karen Drucker (inspired by Melanie Anne Teixeira) 5. THERE IS NO SPOT words: Maggie Cole & Karen Drucker music: John Hoy & Karen Drucker 6. I LOST THE RIGHT TO SING THE BLUES words: Rita Abrams & Karen Drucker music: John Hoy & Karen Drucker 7. I FORGIVE YOU words & music: Karen Drucker 8. MAGIC words: Maggie Cole & Karen Drucker music: Karen Drucker. 9. WE LIVE ON BORROWED TIME words & music: David Friedman 10. HOLD ON TO LOVE words & music: Karen Drucker 11. ONE SMALL STEP words & music: Karen Drucker The Musicians The Band: Fireflies Choir: Melanie Anne Teixeria, Keyboards: John R. Burr Marina Gross-Hoy, David Visini, Miles Drums: Curt More Hatfield, Zane Hatfield Guitars: John Hoy Bass: Rich Girard Back-Up Vocals arranged by Annie Stocking Back-Up Vocals: Annie Stocking, Larry Batiste, Sandy Griffith, Sheilah Glover (on “Magic”) Extra Special Thank You’s to: My family: for your love, support and for always being there… Reverend Karyl Huntley: for inspiration and great laughs… My Dream Team: Maggie Cole, Posi Lyon, Katherine Revoir, Jennifer Mann, Janet Ryan, Kate McCarthy – thank you angels for your constant love and support. To all the musicians, singers, co-writers, & engineers: Hearing what you all brought to these songs is such a gift to me. Thank you! Annie Stocking: You are amazing! Thank you once again for the incredible musical magic that only you can do. -

December 1934) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 12-1-1934 Volume 52, Number 12 (December 1934) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 52, Number 12 (December 1934)." , (1934). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/53 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE s CMCusic S&gmim December 1934 Price 25 Cents <Cy/ i/<)/maJ ($v-e vnM, DECEMBER 19,% Page 695 THE ETUDE THE HARCOURT, BRACE MUSIC DEPARTMENT Albert E. Wier, Editor £Magnifying Christmas PRESENTS FOUR NEW AND DISTINCTIVE MUSIC COLLECTIONS PIECES FOR TWO PIANOS—Four Hands THE DAYS OF THE HARPSICHORD If you do any two-piano playing, this collection of This is the first volume of a series to be known as 48 classic, romantic and modem compositions is in¬ “The Pianist’s Music Shelf.” It contains 80 dispensable for recital, study or recreation. There melodic compositions by more than fifty famous Eng¬ is a 200-word note of general musical interest pre¬ lish, French, German and Italian harpsichord com¬ £Musical Joy ceding each composition, also a page of twelve recital posers in the period from 1500 to 1750. -

Online Appendix (4.86

ONLINE APPENDIX EFFECTS OF COPYRIGHTS ON SCIENCE. EVIDENCE FROM THE WWII BOOK REPUBLICATION PROGRAM BARBARA BIASI, YALE AND NBER PETRA MOSER, NYU AND NBER 11111trdtr 0 APPENDIX A – ADDITIONAL TABLES AND FIGURES TABLE A1 – SUMMARY STATISTICS, BRP BOOKS N Mean St. Dev. Median Min 25 pctile 75 pctile Max All BRP books Original p 271 42.79 179.57 11.15 2.00 6.60 19.15 2000.00 BRP p 283 19.41 41.77 7.50 2.00 3.20 12.50 400.00 Δp 271 24.97 21.33 21.87 -38.89 7.89 40.00 90.00 Chemistry Original p 216 51.18 200.34 11.70 2.00 4.50 22.95 2000.00 BRP p 228 22.43 46.00 8.50 2.00 5.00 15.78 400.00 Δp 216 24.34 21.39 21.76 -38.89 7.52 39.55 90.00 Mathematics Original p 55 9.84 5.77 8.00 3.40 6.00 11.75 32.65 BRP p 55 6.88 4.32 5.75 2.50 3.75 8.75 25.60 Δp 55 27.44 21.11 23.47 0.00 9.72 66.09 74.14 Notes: Means, standard deviations, and median prices for 283 books with German-owned US copyrights that were licensed to US publishers under the 1942 BRP. The variable Δp measures the percentage decline in price, calculated as the difference between the original price and the BRP price, divided by the original price. Price data collected from records of the Alien Property Custodian (1942). -

D and Work Plentiful in Java the East Sy Manufacturing Company

Vol.9 September, 19 2 2 *o.i Our Front Cover and Center Pases EAVING in September of 1921 Mr. and Mrs. Frederick in Java. The pictures and the copy on the center pages Shedd and their two daughters, Marion and Elizabeth, were also contributed by Mr. Shedd, most of the copy being L started on a tour around the globe, which was not taken from letters which he had sent to members of his completed until June of 1922. They visited France, Italy family and friends. We have not had a more interesting and the European countries, then Egypt, Burma, India, center-page spread. Mr. Shedd is one of the directors of the Ceylon, Straits Settlement. Java, China and Japan. Jeffrey Mfg. Co., and has always shown a keen appreciation The picture on the front cover is of a plantation scene ot our employees' publication. KEYBOARD KLIPPINGS A HEART BREAKER—LOST IN THE 10th INNING since their move to the gallc By Poll'janna Wigginton Jeffrey Team Occupies Second Place in League to become a part of Dcpt. 9. One of our girls recently had Ten innings of good baseball were required to decide the cham Mr .Bierly is- back again a letter for a Coal Company in pionship in the Industrial Twilight League when the American Rail looking fine after his vacation. 'est Vriginia for the attention way Express team played our Jeffrey team on Saturday, August Uda Schall spent part of 1 Mr. "Beans," Secretary, and 12th, on the Northwood diamonds. The boys played a hard game vacation at Indian Lake, Oh e noticed another executive of but they finally lost by a score of 5 to 4. -

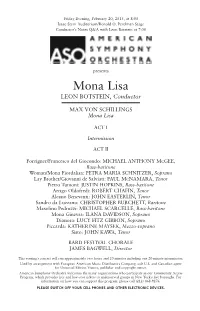

Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor

Friday Evening, February 20, 2015, at 8:00 Isaac Stern Auditorium/Ronald O. Perelman Stage Conductor’s Notes Q&A with Leon Botstein at 7:00 presents Mona Lisa LEON BOTSTEIN, Conductor MAX VON SCHILLINGS Mona Lisa ACT I Intermission ACT II Foreigner/Francesco del Giocondo: MICHAEL ANTHONY MCGEE, Bass-baritone Woman/Mona Fiordalisa: PETRA MARIA SCHNITZER, Soprano Lay Brother/Giovanni de Salviati: PAUL MCNAMARA, Tenor Pietro Tumoni: JUSTIN HOPKINS, Bass-baritone Arrigo Oldofredi: ROBERT CHAFIN, Tenor Alessio Beneventi: JOHN EASTERLIN, Tenor Sandro da Luzzano: CHRISTOPHER BURCHETT, Baritone Masolino Pedruzzi: MICHAEL SCARCELLE, Bass-baritone Mona Ginevra: ILANA DAVIDSON, Soprano Dianora: LUCY FITZ GIBBON, Soprano Piccarda: KATHERINE MAYSEK, Mezzo-soprano Sisto: JOHN KAWA, Tenor BARD FESTIVAL CHORALE JAMES BAGWELL, Director This evening’s concert will run approximately two hours and 20 minutes including one 20-minute intermission. Used by arrangement with European American Music Distributors Company, sole U.S. and Canadian agent for Universal Edition Vienna, publisher and copyright owner. American Symphony Orchestra welcomes the many organizations who participate in our Community Access Program, which provides free and low-cost tickets to underserved groups in New York’s five boroughs. For information on how you can support this program, please call (212) 868-9276. PLEASE SWITCH OFF YOUR CELL PHONES AND OTHER ELECTRONIC DEVICES. FROM THE Music Director The Stolen Smile DVDs or pirated videos. Opera is the by Leon Botstein one medium from the past that resists technological reproduction. A concert This concert performance of Max von version still represents properly the Schillings’ 1915 Mona Lisa is the latest sonority and the multi-dimensional installment of a series of concert perfor- aspect crucial to the operatic experi- mances of rare operas the ASO has pio- ence. -

Kevin John Crichton Phd Thesis

'PREPARING FOR GOVERNMENT?' : WILHELM FRICK AS THURINGIA'S NAZI MINISTER OF THE INTERIOR AND OF EDUCATION, 23 JANUARY 1930 - 1 APRIL 1931 Kevin John Crichton A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2002 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13816 This item is protected by original copyright “Preparing for Government?” Wilhelm Frick as Thuringia’s Nazi Minister of the Interior and of Education, 23 January 1930 - 1 April 1931 Submitted. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of St. Andrews, 2001 by Kevin John Crichton BA(Wales), MA (Lancaster) Microsoft Certified Professional (MCP) Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) (c) 2001 KJ. Crichton ProQuest Number: 10170694 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10170694 Published by ProQuest LLO (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author’. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLO. ProQuest LLO. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.Q. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 CONTENTS Abstract Declaration Acknowledgements Abbreviations Chapter One: Introduction 1 Chapter Two: Background 33 Chapter Three: Frick as Interior Minister I 85 Chapter Four: Frick as Interior Ministie II 124 Chapter Five: Frickas Education Miannsti^r' 200 Chapter Six: Frick a.s Coalition Minister 268 Chapter Seven: Conclusion 317 Appendix Bibliography 332. -

Appendix Three Poetical Essays by Willem

Appendix Three Poetical Essays by Willem Frederik Hermans: Preamble, Behind the Signposts No Admittance and Unsympathetic Fictional Characters For scholarly reasons of reproducibility and verifiability, the reader can find here three English translations of texts written by Hermans that I used for the article ‘The Modernist Affair with Terrorism: The Curious Case of Willem Frederik Hermans’. The translations were made for scholarly usage within the NWO project ‘The Power of Autonomous Literature: Willem Frederik Hermans’ (2010-2015) and/or as course material within the curriculum of Modern Dutch Literature at Utrecht University. Although one of these texts (‘Preamble’) is a fictional text with a dramatized author and one of them is a very short column originally published in a newspaper (‘Behind the Signposts’), I consider them all very important poetical essays on the greater purpose of Hermans’s literature. Preamble (pp. 38-42) is the translation by Ina Rilke of ‘Preambule’, the introduction of the short story collection Paranoia, first published in Dutch in 1953. It was recently republished as part of the seventh volume of Volledige Werken. Behind the Signposts No Admittance (pp. 43-44) is the translation by Sven Vitse of ‘Achter borden Verboden Toegang’, first published in Het Vrije Volk, 25 January 1956. It was republished in Het sadistische universum (1964), now part of the eleventh volume of Volledige Werken. Unsympathetic Fictional Characters (pp. 45-55) is the translation by Michele Hutchison of ‘Antipathieke romanpersonages’, originally published first in De Vlaamse Gids 44 (1960) and republished in the fifth and extended edition of Het sadistische universum (1967), also part of the eleventh volume of Volledige Werken. -

Musicians Who Kept It Quiet During World War II

Musicians who kept it quiet during World War II • Shirley Apthorp From: The Australian November 19, 2011 12:00AM The Spivakovsky-Kurtz trio, from left, Tossy and Jascha Spivakovsky and Edmund Kurtz. Source: Supplied German musicologist and music critic Albrecht Dumling. Picture: Ana Pinto Source: Supplied THE invitation to bomb Berlin caught Albrecht Dumling by surprise. The German musicologist was not being collared by militant extremists in a dark pub. He was visiting the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. There is an exhibit of a Royal Air Force bomber plane with an interactive button to simulate bombing Berlin. "It's like an adventure toy," Dumling recalls. "It felt very strange to be prompted to drop bombs on Berlin. I didn't." Instead, he wrote a book. Vanished Musicians: Jewish Refugees in Australia has just been published by the Bohlau Verlag in Germany. It contains many shocking revelations about a largely forgotten side of Australia's cultural past. Questioning the way history is presented is one of Dumling's chief preoccupations. He was in Canberra to sift through the National Archives, looking into what really happened to Jewish musicians whose flight from Nazi terror brought them to Australia. Today, it is tempting to imagine Australia as a safe haven, where the unjustly persecuted could begin again. The reality was different. Australia was not eager to accept Jewish immigrants. At the Evian Conference of 1938, Australia's trade and customs minister Thomas White, pleading against large-scale Jewish immigration, declared that "as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one". -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Since its launch in 1982, the Marco Polo label has for over twenty years sought to draw attention to unexplored repertoire.␣ Its main goals have been to record the best music of unknown composers and the rarely heard works of well-known composers.␣ At the same time it originally aspired, like Marco Polo himself, to bring something of the East to the West and of the West to the East. For many years Marco Polo was the only label dedicated to recording rare repertoire.␣ Most of its releases were world première recordings of works by Romantic, Late Romantic and Early Twentieth Century composers, and of light classical music. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again, particularly those whose careers were affected by political events and composers who refused to follow contemporary fashions.␣ Of particular interest are the operas by Richard Wagner’s son Siegfried, who ran the Bayreuth Festival for so many years, yet wrote music more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck. To Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich, Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan), and Bruder Lustig, which further explores the mysterious medieval world of German legend is now added Der Heidenkönig (The Heathen King).␣ Other German operas included in the catalogue are works by Franz Schreker and Hans Pfitzner. Earlier Romantic opera is represented by Weber’s Peter Schmoll, and by Silvana, the latter notable in that the heroine of the title remains dumb throughout most of the action. -

Gregory Collins - Poems

Poetry Series gregory collins - poems - Publication Date: 2008 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive gregory collins(fall '72) see anyone and everyone in the back left-hand corner of heaven......... www.PoemHunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive 1 1968 'we have the opportunity to make America a better nation' Doctor Martin Luther King Jr. 'there are those who look at the way things are asking why. I dream of things that never were, and ask why not' Robert Kennedy The whole frame was swaying as if to scratch gropingly and fault-ridden. Even gold hearted friends were turning into falling firebirds, and they stay forever in a dream like when a peacock dozes. But the clean mirror of us all was sobbing speechless in the skies about a distant shore as lonely as death. Even the size of the stars beat their heads against the town bell. Because there was my father on a rock's edge of the soul. Kneeling in his bedroom, crying with his empty M-1 rifle holding up his strength. He had joined the National Guard in the summer of '63, and was not praying mistakenly as if drunk swallows the flame of fire. But the race riots had begun in New Haven and Hartford, and he had some semblance of duty: that eight phases of Buddha feeling. The smearing of blood unable to hear it's own voice. The vast heavens like wings that leave bruises in the heart. They are timeless and not yet done. and my mother stood outside the room like an immaculate petal, yesterday, today, and tomorrow still. -

Das Strittige Gebiet Zwischen Wissenschaft Und Kunst« Artur Kutscher Und Die Praxisdimension Der Münchner Theaterwissenschaft

Università degli Studi di Milano Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Facoltà di Fakultät für Studi Umanistici Geschichts- und Kunstwissenschaften Dipartimento di Department Lingue e letterature straniere Kunstwissenschaften Corso di dottorato in Studiengang Lingue, Letterature e culture straniere Theaterwissenschaft (Promotion) XXVII ciclo Coordinatore del dottorato: Prof. Iamartino a.a. 2013-2014 »Das strittige Gebiet zwischen Wissenschaft und Kunst« Artur Kutscher und die Praxisdimension der Münchner Theaterwissenschaft L-LIN/13 Inaugural-Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Philosophie an der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Chiara Maria Buglioni Tutor: Prof. Marco Castellari Betreuer: Prof. Dr. Christopher Balme Inhalt Vorwort ……………………………………………………………………………….. I Teil I. Ausgangspunkte Die Praxisdimension …………………………………………………………………………. 1 Die Theaterwissenschaft zwischen Theorie und Praxis • Wissenschaftlicher Diskurs und ausgehandelte Praxis • Situiertes Lernen nach Jean Lave und Etienne Wenger Die Praxis in der Theorie des situierten Lernens ………………………………………….. 28 Die soziale Landschaft der Praxis Entwicklung einer Lerngemeinschaft, Lehrtätigkeit und Performativität ………………. 41 Die theaterwissenschaftliche Lerngemeinschaft oder: der Kutscher-Kreis • Performative Aspekte des gemeinsamen Lernens Teil II. Potentialphase der Münchner Theaterwissenschaft München, der kulturelle Pol ………………………………………………………………… 52 Theaterdebatten und -experimente in Münchner praxisorientierten Gruppierungen • Eine künstlerische und gesellschaftliche -

The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect

PRINCE June 7, 1958 — Third Thursday in April The Ultimate Listening-Retrospect 70s 2000s 1. For You (1978) 24. The Rainbow Children (2001) 2. Prince (1979) 25. One Nite Alone... (2002) 26. Xpectation (2003) 80s 27. N.E.W.S. (2003) 3. Dirty Mind (1980) 28. Musicology (2004) 4. Controversy (1981) 29. The Chocolate Invasion (2004) 5. 1999 (1982) 30. The Slaughterhouse (2004) 6. Purple Rain (1984) 31. 3121 (2006) 7. Around the World in a Day (1985) 32. Planet Earth (2007) 8. Parade (1986) 33. Lotusflow3r (2009) 9. Sign o’ the Times (1987) 34. MPLSound (2009) 10. Lovesexy (1988) 11. Batman (1989) 10s 35. 20Ten (2010) I’VE BEEN 90s 36. Plectrumelectrum (2014) REFERRING TO 12. Graffiti Bridge (1990) 37. Art Official Age (2014) P’S SONGS AS: 13. Diamonds and Pearls (1991) 38. HITnRUN, Phase One (2015) ALBUM : SONG 14. (Love Symbol Album) (1992) 39. HITnRUN, Phase Two (2015) P 28:11 15. Come (1994) IS MY SONG OF 16. The Black Album (1994) THE MOMENT: 17. The Gold Experience (1995) “DEAR MR. MAN” 18. Chaos and Disorder (1996) 19. Emancipation (1996) 20. Crystal Ball (1998) 21. The Truth (1998) 22. The Vault: Old Friends 4 Sale (1999) 23. Rave Un2 the Joy Fantastic (1999) DONATE TO MUSIC EDUCATION #HonorPRN PRINCE JUNE 7, 1958 — THIRD THURSDAY IN APRIL THE ULTIMATE LISTENING-RETROSPECT 051916-031617 1 1 FOR YOU You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ me away 1 For You 2. In Love (In love) April 7, 1978 Ever since I met you, baby I’m fallin’ baby, girl, what can I do? I’ve been wantin’ to lay you down I just can’t be without you But it’s so hard to get ytou Baby, when you never come I’m fallin’ in love around I’m fallin’ baby, deeper everyday Every day that you keep it away (In love) It only makes me want it more You’re breakin’ my heart and takin’ Ooh baby, just say the word me away And I’ll be at your door (In love) And I’m fallin’ baby.