Development, Politics, and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature Review on Decentralization in Lesotho

Public Disclosure Authorized Kingdom of Lesotho Local Governance, Decentralization and Demand-Driven Service Delivery VOLUME II: ANNEXES Public Disclosure Authorized DRAFT REPORT - CONFIDENTIAL WORLD BANK Public Disclosure Authorized IN COLLABORATION WITH GOVERNMENT OF LESOTHO, GTZ, AND FAO JUNE 27, 2007 Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents ANNEX 1: LITERATURE REVIEW ON DECENTRALIZATION IN LESOTHO 3 ANNEX 2: DETAILED ASSESSMENT OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ACT 10 ANNEX 3A: STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE PROVISIONS OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT AS AMENDED .10 ANNEX 3.B STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION OF THE ACT IN THE SECTORS ..........................................................18 ANNEX 3: CONCEPT PAPER ON CHANGE MANAGEMENT 27 ANNEX 4: PERCEPTIONS OF DECENTRALIZATION AT COMMUNITY AND DISTRICT LEVEL 31 ANNEX 4. 1 ADDITIONAL DETAILS ON METHODOLOGY, CCS AND VILLAGES ..................................................31 ANNEX 4.2 THE STORY OF MR POTSO CHALLENGING THE RIGHT TO FINE WITHOUT ISSUING RECEIPT ............32 ANNEX 5: PRIORITIES, ACCESS AND QUALITY OF SERVICES 33 ANNEX TABLE 5.1: PRIORITY AND ACCESS TO SERVICES ACROSS VILLAGES WITH DIFFERENT ROAD ACCESS ..33 ANNEX FIGURE 5.1: SERVICE PRIORITY IN THABA-TSEKA ...............................................................................34 ANNEX FIGURE 5.2: SERVICE ACCESS IN THABA-TSEKA..................................................................................35 ANNEX TABLE 5.2: STATUS OF SERVICES FOUND IN VILLAGES VISITED BY THE TEAM..................................36 ANNEX -

Lesotho Vulnerability Assessment Committee

2016 Lesotho Government Lesotho VAC Table of Contents List of Tables ................................LESOTHO................................................................ VULNERABILITY.............................................................................. 0 List of Maps ................................................................................................................................................................................ 0 Acknowledgments ................................ASSESSMENT................................................................ COMMITTEE................................................................ ... 3 Key Findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 INTERVENTION MODALITY SELECTION Section 1: Objectives, methodology and limitations ................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Objectives ................................In light ................................of the findings................................ from the LVAC................................ Market Assessment................................ that assessed....... 9 the functionality and performance of Lesotho’s food markets, LVAC proceeded to 1.2 Methodology -

The Impact of Political Parties and Party Politics On

EXPLORING THE ROLE OF POLITICAL PARTIES AND PARTY SYSTEMS ON DEMOCRACY IN LESOTHO by MPHO RAKHARE Student number: 2009083300 Submitted in the fulfilment of the requirements for the Magister Degree in Governance and Political Transformation in the Programme of Governance and Political Transformation at the University of Free State Bloemfontein February 2019 Supervisor: Dr Tania Coetzee TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages DECLARATION .................................................................................................................................... 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ...................................................................................................................... 5 List of abbreviations and acronyms ................................................................................................... 6 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................................. 8 Chapter 1 ............................................................................................................................................... 9 Introduction to research ....................................................................................................................... 9 1.1 Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 9 1.2 Problem statement ..................................................................................................................... -

LESOTHO SITUATION REPORT - June 2016

UNICEF LESOTHO SITUATION REPORT - June 2016 Lesotho Humanitarian Situation Report June 2016 ©UNICEF/Lesotho/2015 Situation in Numbers Highlights UNICEF provided support for the completed Lesotho Vulnerability 310,015 Assessment Committee (LVAC), which revised the number of people Children affected requiring humanitarian assistance from 725,000+ down to 679,437. UNICEF is reaching 69,000 of the most vulnerable children (51% girls), through its Cash Grant Top Up response, which provides relief 64,141 for families in response to the food price shock during the winter Children under 5 affected months. The rapid assessment of schools indicates that 30% of schools are in need of immediate water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) 69,000 support. This means there is insufficient water for over 100,000 Vulnerable children in need of social children in all districts. Poor WASH services in schools have shown safety nets to result in low attendance and high drop-out rates. UNICEF’s WASH interventions are progressing in Mohale’s Hoek (the most drought stricken district) with 7 community tanks installed in the 534,508 most vulnerable communities. These communities will receive water People currently at risk of food tankering services, reaching an estimated 5,000 people (55% female; insecurity 41% children). During the first week of July, construction/re-habilitation will begin on community water supply schemes in Berea, Botha Buthe and 679,437 Mohale’s Hoek. This will benefit 15 most vulnerable communities, reaching 23,809 people (56% female; 45% are children). People in need of humanitarian Water purification and WASH messaging are being undertaken in assistance (LVAC) Mokhotlong and Thaba Tseka reaching 80,000 people (52% female; *All numbers above are from the Rapid Drought 49% children), starting the first week of July. -

Terms of Reference

Terms of Reference Position Title: Consultancy on Community Development Projects Identification and Feasibility Study Type of Contract: Consultancy service Duration of Assignment: April 2021 to May 2021 (25 working days) 1. BACKGROUND: International Organization for Migration (IOM) has been advocating for the adoption of sustainability-oriented reintegration policies that respond to the economic, social and psychosocial needs of returning migrants while also benefiting communities of origin and addressing structural challenges to reintegration. With the aim to support sustainable reintegration of returnees who continue to come back to Lesotho affected by COVID-19, as well as host communities in migration affected areas, the Government of Japan has provided financial support to International Organization for Migration (IOM) under the project called ‘’Socio-Economic Reintegration of Returnees and other vulnerable members in migration affected areas severely impacted by COVID-19 pandemic.’’ The project will be implemented from March 2021 for 12 months. In this project, IOM intends to apply part of the reintegration assistance modality which proved to be effective and productive based on the global IOM Reintegration project which will be modified and tailored to the Lesotho context and the urgent needs of returnees pressured by continuous challenges of COVID-19. The project has three outcomes. Outcome 1: GoL has improved its ability to successfully implement reintegration programmes; Outcome 2: Vulnerable Basotho returnees impacted by COVID-19 have enhanced their livelihoods through restoring their dignity, income generating opportunities and enhanced their living conditions in the district of origin; and Outcome 3: GoL (Local Government) has improved its ability to enhance social unity / cohesion through community development initiative. -

Integrated Acute Food Insecurity Phase Classification

INTEGRATED ACUTE FOOD INSECURITY PHASE CLASSIFICATION MAY 16/MAR 17 THE KINGDOM OF LESOTHO IPC analysis conducted from 24 to 30 May 2016 for all 10 districts of Lesotho based on primary data collected by LVAC and partners in May 2016 and secondary data collected from Jan. 2016 onwards. Projected analysis requires an update in October 2016. AGGREGATE NUMBERS FOR WORST PERIOD KEY FOOD INSECURITY OUTCOMES AS OF MAY 2016 – JULY TO OCTOBER 2016 – Despite current analysis corresponding to harvest/post-harvest Proportions of households and number of people in need of urgent period, 19% of households had poor food consumption, and 45% had support to protect their livelihoods and reduce food gaps and classified borderline food consumption. using IPC1: In Berea, Mafeteng, Mohale’s Hoek, Quthing and Thaba-Tseka, over Thaba-Tseka 40% (48,903 people) 20% of the rural households spent more than 75% of their cash in Maseru 25% (55,623 people) food purchase. In other districts the same expenditure pattern is Mafeteng 45% (67,204 people) experienced by 10-16% of rural households. Qacha’s Nek 45% (23,950 people) Generally, 13% of households engaged in crisis and emergency Leribe 35% (86,918 people) livelihood coping strategies, indicating that households reduced food Mohale’s Hoek 33% (50,245 people) consumption rather than depleting livelihood assets Quthing 43% (48,448 people) Global Acute Malnutrition was below 5% in all districts except in Mokhotlong 25% (23,625 people) Mohale’s Hoek, which had a GAM prevalence of 6.6%. Butha Buthe 20% (16,616 people) Berea 51% (88,725 people) Total Approx. -

Implications for Consolidation of Democracy in Lesotho by Libuseng Malephane

Contesting and turning over power: Implications for consolidation of democracy in Lesotho By Libuseng Malephane Afrobarometer Policy Paper No. 17 | February 2015 Introduction Since its transition to electoral democracy in 1993, Lesotho has experienced a series of upheavals related to the electoral process. Election results were vehemently contested in 1998, when the ruling Lesotho Congress for Democracy (LCD) won all but one of the country’s constituencies under a first-past-the-post electoral system, and a military intervention by the Southern African Development Community (SADC) was required to restore order. A mixed member proportional (MMP) model introduced in the run-up to the 2002 general elections resulted in more parties being represented in Parliament. The MMP model also led to the formation of informal coalitions as political parties endeavoured to maintain or increase their seats in Parliament in the 2007 elections (Kapa, 2007). Using a two-ballot system, with one ballot for constituency and another for the proportional-representation (PR) component, the elections preserved the ruling LCD’s large majority in Parliament and precipitated another protracted dispute between the ruling and opposition parties over the allocation of PR seats. Mediation efforts by the SADC and the Christian Council of Lesotho led to a review of the Constitution and Electoral Law. The resulting National Assembly Electoral Act of 2011 provides for a single-ballot system that allows voters to indicate their preferences for both constituency and PR components of the MMP system (UNDP, 2013). Meanwhile, the new All Basotho Convention (ABC), which had broken away from the LCD in 2006, became the largest opposition party in Parliament after the 2007 elections. -

Basotho Speak on the Proposed Renaming of Major Roads

Sunday April 14, 2019 Public EyeOn Sunday 1 Woes buffet Lekokoaneng Best Sunday News sandstone miners News ublic ye Page 5 PApril 14 , 2019 www.publiceyenews.com E On EST .1997| vol 22 No 17 Sunday ‘Don’t name roads after politicians’ Concern over Govt denies Lesotho’s grabbing maternal Likoti’s mortality rate pension - Page 4 - Page 7 01042019 Met Funeral Strip.pdf 1 4/11/2019 6:18:29 PM C M Y CM MY How deep is your CY CMY K 2 Public EyeOn Sunday Sunday April 14, 2019 News ‘Don’t name roads after politicians’ . Basotho speak on the proposed renaming of major roads Former Prime Minister, Dr Ntsu Mokhehle last week adopted a motion “Our children will even have Former Prime Minister, Morena Leabua Jonathan proposed by ‘Mapulumo Hlao more interest if they see the names urging the government to assign of our former Prime Ministers on ASERU– Parliament’s Instead, chiefs and other new names to the Main North I a regular basis which would lead decision to rename apolitical figures who have and Main South I Roads, which to always remember the role these Mmajor national roads made genuine sacrifices for this should be named after former politicians have played for the after current and past premiers kingdom are the only ones that prime ministers, Morena Leabua country to be where it is today,” has attracted mixed reactions merit such an honour, some Jonathan and Dr Ntsu Mokhehle, he stressed. from Basotho, with some saying Basotho have said. respectively. He advised the government to no politician deserves such an One ’Mats’epo Tsiane, a Member of Parliament for put in place a proper engagement honour since they all tend to Maseru resident, told the media Mosalemane, Tsoinyane Rapapa process with the community to disappoint the electorate once this week she does not like the had moved that after the word educate them about political they get power. -

Lesotho Coups D'etat: Political Decay and Erosion of Democracy

JOERNAAUJOURNAL PHERUDl/BARN ARD LESOTHO COUPS D'ETAT: POLITICAL DECAY AND EROSION OF DEMOCRACY M.L. Pherudi' and S.L. Barnard2 INTRODUCTORY BACKGROUND OF LESOTHO The Basotho nation and its proto state came into being in the first half of the 19th centmy. In 1868 the territoiy became the colonial possession of the British Crown.' As a colonial possession, Britain entrenched its colonial policies in a new ly acquired territoiy. Its loss of political sovereignty and indigenous independence was implicit in the Annexation Proclamation which declared that "the said tribe of the Basotho shall be, and shall be taken to be to all intents and pmposes British subjects, and the territoiy of the said tribe shall be, and shall be taken to be British territory". 4 Bringing the Basotho under British subjugation meant an end to and the amelioration of the communal practices and the beliefs of the Basotho. As British subjects, the Basotho had to conform to the voice of the new masters. This confor mity was emphasised in the churches, schools and communal assemblies (Li pitsong) under the supervision of the British officials. Some chiefs collaborated with the new rulers to suppress possible insurrection among the Basotho. Rugege argued that the Britons subjugated the Basotho because they wanted to l!Vert a possible annihilation of the people in the continuing wars with the Boers. 5 Protecting the Basotho against Boer intrusion from the Free State was an over simplification of the state of affairs. It is true that the Free State wanted to incorpo rate Lesotho but it is important also to recognise that Britain had an ambition of acquiring colonies from Cape to cairo. -

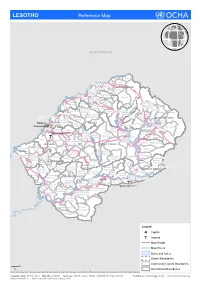

LESOTHO Reference Map

LESOTHO Reference Map SOUTH AFRICA Makhunoane Liqobong Likila Ntelle n Maisa-Phoka Ts'a-le- o d Moleka le BUTHA BUTHE a Lipelaneng C Nqechane/ Moteng Sephokong Linakeng Maputsoe Leribe Menkhoaneng Sekhobe Litjotjela Likhotola/ LERIBE Hleoheng Malaoaneng Manka/ Likhakeng Matlameng Mapholaneng/ Fobane Koeneng/ Phuthiatsana Kolojane Lipetu/ Kao Pae-la-itlhatsoa -Leribe Fenyane Litsilo -Pae-la-itlhatsoa Mokhachane/ Mamathe/Bulara Mphorosane Molika-liko Makhoroana Limamarela Tlhakanyu/Motsitseng Teyateyaneng Seshote Mapholaneng/ Majoe-Matso/ Meno/ Lekokoaneng/Maqhaka Mohatlane/ Sebetia/Khokhoba Pae-la-itlhatsoa Matsoku -Mapholaneng MOKHOTLONG Lipohong Thuapa-Kubu/ Moremoholo/ Katse Popa Senekane BEREA Moshemong Maseru Thuathe Koali/ Taung/Khubelu Mejametalana p Mokhameleli Semenanyane Mokhotlong S Maluba-lube/ Mateanong e Maseru Suoane/ m Rafolatsane Thaba-Bosiu g Ratau e Liphakoeng n Bokong n e a Ihlo-Letso/ Mazenod Maseru Moshoeshoe l Setibing/ Khotso-Ntso Sehong-hong e Tsoelike/ Moeketsane h Pontseng/ Makopoi/ k Mantsonyane Bobete p Popa_MSU a Likalaneng Mahlong Linakaneng M Thaba-Tseka/ Rothe Mofoka Nyakosoba/Makhaleng Maboloka Linakeng/Bokhoasa/Manamaneng THABA TSEKA Kolo/ MASERU Setleketseng/ Tebang/ Matsieng Tsakholo/Mapotu Seroeneg S Mashai e Boleka n Tsa-Kholo Ramabanta/ q Methalaneng/ Tajane Moeaneng u Rapo-le-boea n Khutlo-se-metsi Litsoeneng/Qalabane Maboloka/ y Sehonghong Thaba-Tsoeu/ Monyake a Lesobeng/ Mohlanapeng Mathebe/ n Sehlaba-thebe/ Thabaneng Ribaneng e Takalatsa Likhoele Moshebi/ Kokome/ MAFETENG Semonkong Leseling/ -

National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report

The Government of Lesotho National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report October 2007 The Government of Lesotho National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho Final Report October 2007 Report no. 64131-0-13 Issue no. 3.2 Date of issue 20 October 2007 Prepared NBP Checked DH/ABR/CW/GB Approved NBP National Electrification Master Plan for Lesotho - Final Report 1 Table of Contents 1 Executive Summary 6 1.1 Introduction 6 1.2 Electrification Target 6 1.3 Settlements 7 1.4 Load Forecast 8 1.5 Technical Standards 9 1.6 Systems in Remote Areas 10 1.7 Transmission System 11 1.8 Distribution Systems 11 1.9 Financial Aspects 13 1.10 Prioritisation of Settlements 14 1.11 Project Schedule Years 1 to 5 - Distribution 15 1.12 Project Schedule for Years 6 - 15 - Distribution 18 1.13 Allocation of Responsibilities 19 1.14 Future Service Models for Electricity Supply 21 1.15 Tariffs and Connection Fee 21 1.16 Subsidies 22 1.17 Institutional Development and Training 23 1.18 Monitoring and Evaluation Framework 23 1.19 Environmental Issues 25 2 Introduction 27 2.1 Electrification Target for Lesotho 27 2.2 Balancing Policy Objectives 28 2.3 Planning Criteria and Approach 29 2.4 Report Structure and Terminology 32 3 Background 34 3.1 Context 34 3.2 Energy Policy and Power Sector Reform 35 3.3 Institutions Involved in Electrification 37 3.4 Existing Power System 42 P:\64131A\3_Pdoc\DOC\Final Report\færdige\Final Report October 2007\Final Report\Final Report-october.doc . -

Letlhogonolo Mpho Letshele

COPYRIGHT AND CITATION CONSIDERATIONS FOR THIS THESIS/ DISSERTATION o Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. o NonCommercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. o ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. How to cite this thesis Surname, Initial(s). (2012). Title of the thesis or dissertation (Doctoral Thesis / Master’s Dissertation). Johannesburg: University of Johannesburg. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/102000/0002 (Accessed: 22 August 2017). A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE RECURRENCE OF COUPS IN THE KINGDOM OF LESOTHO – 1970-2014 A Dissertation Submitted to the Department of Politics and International Relations of the Faculty of Humanities at the University of Johannesburg by Letlhogonolo Mpho Letshele 201417806 October 2019 In Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN POLITICS AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS Johannesburg, South Africa Supervisor: Prof Annie Barbara Chikwanha Co-Supervisor: Prof Chris Landsberg 1 ABSTRACT Since its independence, the Kingdom of Lesotho has experienced the recurrence of coups (1970-2014). A process of re-democratisation was attempted in the country in 1993 but another coup succeeded the elections. The next elections in 1998 were marked by the worst political violence in the history of Lesotho. Electoral reforms were then introduced in 2002. Still, the reforms did not prevent the coup attempt in 2014.