Thesis. (5.677Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

26 February 1992

. ,< 0c ) ty ...., * TOO'AV: LATEST FROM THE NA * ELNATAN DECISION SOON * LANGUAGE 'ISSUE'HIJACKS DEBATE .* . I Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.511 . Wednesday February 26 1992 Whites in Namibia to Nul~matlonoured NEW DELHI: Namibian President Sam Nujoma yes terday received the US$ 58000 Indira Gandhi prize for vote in SA referendum peace, and called on developing nations to unite against economic manipulation by rich countries. THOUSANDS of whites in The number of South Afri ..:. GRAHAM HOPWOOD can citizens residing in Na "The east-west confrontation has disappeared now ... south Namibia could take part south co-operation must be promoted so that we can compete mibia who have not taken up in the referendum on and bargain with the rich nations," Nujoma said at a news March 17 which will ask erendum. Namibian citizenship and A report in a Walvis Bay remain on temporary or per conference. .,._ After conferrjng with Indian Prime Minister PV Nara South Africa's white elec weekly newspaper yesterday manent residence permits is simha Rao on efc;noiAfcrelations, Npjoma was awarded the torate if they still support referred to expectations that not known, but is probably well Gandhi prize for his efforts toward peace and development. FW de Klerk's reform thousands of whites living in into the thousands. President Ramaswamy Venkataraman, who gave the prize, policy aimed at negotiat Namibia will vote in the refer The disputed Walvis Bay congratulated the Namibian President for his "valiant contri ing a new constitution. endum. enclave will also participate in bution in leading the people of Namibia to liverty". -

Sports Medicine Sportgeneeskunde

SOUTH AFRICAN JOURNAL OF SPORTS MEDICINE SPORTGENEESKUNDE JOURNAL OF THE S.A. SPORTS MEDICINE ASSOCIATION TYDSKRIF VAN DIE S.A. SPORTGENEESKUNDE-VERENIGING National Advisory Board Editor in Chief: VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 FEB/MARCH 1992 Clive Noble Associate Editors: Prof ID Noakes Dawie van Velden Advisory Board: CONTENTS Traumatology: Etienne Hugo Physiotherapy: Editorial Comment Joyce Morton Health care for the future sportsmen o f South Nutrition: Africa ........................................................................ 3 Mieke Faber Biokinetics: Cricket Martin Schwellnuss Epidemiology: Cricket injuries while on tour with the South Derek Yach African team in India - C Smith ......................... 4 Radiology: Alan Scher Physiology Notes Pharmacology: Notes on muscle spindles - M Frescura ........... 9 John Straughan ) Physical Education: . 2 Hannes Botha Nutrition 1 0 Internal Medicine: Macro-nutrient intake of various athletes as 2 Francois Relief d reported in the literature - M Faber ................. 11 e t a d International Advisory Board ( Physiotherapy r Lyle J Micheli e A review of the McConnell approach to the h Associate Clinical Professor of s i management of patellofemoral pain - l Orthopaedic Surgery b Boston, USA J Morton .................................................................. 17 u P Chester R Kyle Restriction of ankle and foot movements using e h Research Director, Sports t the standard elastic ankle guard - 1 Seels, Equipment Research Associates y J Begley, F Futcher and J Mitchell ................. 20 -

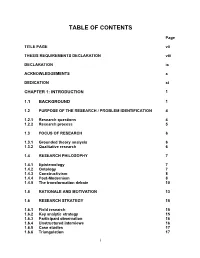

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TITLE PAGE vii THESIS REQUIREMENTS DECLARATION viii DECLARATION ix ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS x DEDICATION xi CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PURPOSE OF THE RESEARCH / PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION 4 1.2.1 Research questions 4 1.2.2 Research process 5 1.3 FOCUS OF RESEARCH 6 1.3.1 Grounded theory analysis 6 1.3.2 Qualitative research 6 1.4 RESEARCH PHILOSOPHY 7 1.4.1 Epistemology 7 1.4.2 Ontology 7 1.4.3 Constructivism 8 1.4.4 Post-Modernism 8 1.4.5 The transformation debate 10 1.5 RATIONALE AND MOTIVATION 13 1.6 RESEARCH STRATEGY 15 1.6.1 Field research 15 1.6.2 Key analytic strategy 15 1.6.3 Participant observation 16 1.6.4 Unstructured interviews 16 1.6.5 Case studies 17 1.6.6 Triangulation 17 i 1.6.7 Purposive sampling 17 1.6.8 Data gathering and data analysis 18 1.6.9 Value of the research and potential outcomes 18 1.6.10 The researcher's background 19 1.6.11 Chapter layout 19 CHAPTER 2: CREATING CONTEXT: SPORT AND DEMOCRACY 21 2.1 INTRODUCTION 21 2.2 SPORT 21 2.2.1 Conceptual clarification 21 2.2.2 Background and historical perspective 26 2.2.2.1 Sport in ancient Rome 28 2.2.2.2 Sport and the English monarchy 28 2.2.2.3 Sport as an instrument of politics 29 2.2.3 Different viewpoints 30 2.2.4 Politics 32 2.2.5 A critical overview of the relationship between sport and politics 33 2.2.5.1 Democracy 35 (a) Defining democracy 35 (b) The confusing nature of democracy 38 (c) Reflection on democracy 39 2.3 CONCLUSION 40 CHAPTER 3: SPORT IN A GLOBAL CONTEXT 42 3.1 INTRODUCTION 42 3.2 A GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE OF SPORT 43 -

BSB Se Turf Begin Sit

5 15 DIE NUWE SUID-AFRIKA 18 Me; 1990 ~... ','. ' BSB se turf begin sit Kol Joe Verster (foto links), besturende di Vrye Weekblad gese het dat Verster'n magsbe JACQUES PAUW rekteur van die Burgerlike Samewerkingsburo luste man is en dat die BSB vir politieke doel DIE klandestiene BSB, tot onlangs nog 'n web (BSB), het verskuil agter 'n welige baard, pruik eindes misbruik mag word. Hy het gese hy g10 van intrige , is die week grootliks deur sy eie en donkerbril gese: "Ons dink in tenne van daar is reeds 'n interne weerstandbeweging. Boere-Rasputin ontrafel toe hy voor die Harms selfbehoud ... ons is slagoffers van die nuwe Botes het getuig dat hy in Maart verlede jaar kommissie erken het dat die organisasie homself bedeling." genader is om 'n Durbanse prokureur wat 'n ten koste van die regering beskenn, huidige Intussen het Pieter Botes, gewese waarne senior lid van die ANC sou wees, te vennoor. politieke gebeure hom bedreig en hy in selfbe mende streekbestuurder van die BSB, gister lang optree. middag begin getuig nadat hy verlede week in Vervo/g op b/2 e rei CHRISTELLE TERREBLANCHE AS Welkom dlt sonder 'n rasse-bloedbad gaanoorleef, sal dlt goed gaan met die res van Suld-Afrlka. Dlt was gister die gevoel oor die Vry staatse myndorp waar rassegevoelens breekpunt bereik het. 'n Maand gelede is die spot nog gedryfmet die naam Welkom vir 'n stad waarin meer as drlekwart van die Inwoners nie juls welkom voel nle. Die week Is twee blank e inwoner s deur 'n groep swart mynwerkers ver moor en nou begin dit Iyk asof die spiraal van geweld, In die tr adlsle van die Amerlkaansesuidevan 'n paar dek ades gelede, geen einde ken nie. -

Masculine and Racial Identities of Black Rugby Players: a Study of a University Rugby Team

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Wits Institutional Repository on DSPACE Masculine and racial identities of black rugby players: A study of a university rugby team By Lungako C. Mweli 464905 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Witwatersrand Johannesburg 2015 1 Lungako Mweli 464905 University of the Witwatersrand DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY I, LungakoMweli, hereby declare that this research report is my own original work. In the instances where the work of another person has been referenced or quoted, it has been cited and fully referenced according to the American Psychological Association (APA) format. I am fully aware of the implications of using plagiarised work in a project of this nature. ……………………………………. Lungako C Mweli ……………………………………. Date Department of Psychology University of the Witwatersrand Johannesburg 2015 2 Lungako Mweli 464905 University of the Witwatersrand TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………….6 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………...8 Chapter One ……………………………………………………………………………….9 1.1 Introduction and aim of the study……………………………………………………….9 1.2Rationale of the study………………………………………………………………….10 1.3 Conceptual framework…………………………………………………………………12 1.4The report structure…………………………………………………………………….13 Chapter Two: Literature review…………………………................................................14 2.1 Introduction…………………………………………………………………………….14 2.2 Sport and race in -

3 April 1992

i ! I " I I .Brlnglng Africa South * Walvis issue Namibians J'" '~l c want,more I, I . GRAHAM HOPWOOD Prisoners NAMIBIAN President Sam Nujoma yesterday declared an emergency situation throughout the country in view ACTION. with AIDS of the disastrous drought aftlicting the country. •• I' The President told a press survival of breeding animals. 0 ,to go free conference attended by cabi These measures will com 99,1 /0 in poll push for stronger stand net ministers and diplomats that plement actions already taken 1WO prisOners at Wind the Government was acting im by the Government - the set f GWEN LlSTER hoek's Central Prison are mediately to avert the crisis ting up a Cabinet Committee to be released sOQn after getting out of all proportion. and National Committee, which THE MORE than 1 they were tested AIDS The immediate coricems of includes regional commission positive, according to the Government are the need ers, leaders ofpolitical parties, 000 people who took radio reports yesterday. to supply food to vulnerable the Namibia Agricultural Un groups, to ensure there is a ion and the Coun:il of Cllurches part in The Namib An NBC report quoted a prison official as say water supply in all areas and to in Namibia, to deal with the ian's mini-referen sustain livestock production, ing that both inmates, a drought. Both committees are dum voted resound the President said. chaired by Prime Minister Rage man and a woman, were ingly for the Govern Nujoma also announced new Geingob. serving sentences for measures to deal with what be The Cabinet Committee on ment to take a stronger murder. -

Ei-Aseb'lewenslank Na Tronk

• TODAY~ MORE BATTLEFIELD SUCCESS FOR UNITA· WOMEN ON THE MARCH" SAN'LAM NAMIBIAT-URNS 50'· '-' Bringing Africa South Tuesday June 1 1993 * Lubowski issue • rl e ATTORNEY-GENERAL Hartmut Ruppel yesterday confirmed the Government's re fusal to take up the cases ofseveral police and one army officer for an action against The Namibian. Recently The N amibian published a report citing two sw'om affidavits which allege that several high ranking police and one anny officer were present at a meeting at which the assassination of Swapo activist Anton Lubowski was discussed. sentence -for One ofthe officers named. the CID's lwnbo Smit, was in ' fact the chief investigating officer in the Lubowski murder. He recently placed his docket in front of the Olief Magistrate for a decision on an inquest date. It is believed that his investigation finds unknown elements of the Civil Co-operation Bureau (CCB) in South Africa, responsible for the • • killing. Last week a local newspaper reported that Smit, and the other officers named. Flip Nel, Riaan White, Daan Oberbolzer, as well as Colonel Des Radmore an SlaVln ofthe NDF, had approached the Government Attor- cont. on page 2 Namibians TYAPPA NAMUTEWA in Cuba to ANDRIES Ei-Aseb was yesterday given a triple life sentence for the come home brutal murder of three young San ALL 325 Namibian stu children, who were gruesomely dents and teachers pres ently in Cuba are to return hacked to death near Tsumeb last home at a cost of RI,45 million, Cabinet an Ei-Aseb's co-accused in the San slaying case, nounced yesterday. -

2013 Annual Report

Annual Report Report 20132012 / 2013 stemcellsaustralia.edu.au 2 STEM CELLS AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 “STEM CELL SCIENCE IS AN EXTREMELY FAST MOVING FIELD WITH NEW APPLICATIONS BEING REPORTED WORLDWIDE ON A DAILY BASIS” Professor David de Kretser Chairman Supported by: Our Partners: Cover image: Neuronal precursor cells (Lincon Stamp, UoM) stemcellsaustralia.edu.au 3 STEM CELLS AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Vision statement: To discover how to regulate stem cells in order to harness their potential for therapeutic purposes and to generate economically valuable biotechnologies. Contents Chairman’s Report 4 Program Leader’s Report 5 Highlights 6 Research Programs 8 Education, Ethics, Law and Community Awareness Unit 13 Research Support 16 Leadership and Governance 18 Our People 22 Management Report 31 Performance 32 Awards and Scholarships 35 Publications 36 Conference Participation 44 Participation in Community Events 49 Media Coverage 50 Pei Er and Xaoli Chen networking at the Annual Retreat Financial Statement 51 stemcellsaustralia.edu.au 4 STEM CELLS AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Chairman’s Report Stem Cells Australia is a Special Research Initiative in Stem Cells Australia core researchers are building international Stem Cell Science launched in 2011 and funded by the collaboration supported by: Australian Research Council that brings together expert • a Department of Foreign Affairs researchers in this field from across the country and and Trade grant to foster encourages international collaboration. collaborative workshops with Kyoto University’s Institute for Integrated Cell-Material Sciences (iCeMS), and • the Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Networks of Excellence grant was awarded for research into adult cardiac stem cells In 2013, Stem Cells Australia established a strategic fund to foster further collaboration between partners and provide the opportunity to bring in new collaborators to join our research community. -

Different Perspectives in Researching Genealogy by Abrie De Swardt - Chairman of the Southern Cape Branch of the Genealogical Society of South Africa

Different perspectives in researching Genealogy by Abrie de Swardt - Chairman of the Southern Cape Branch of the Genealogical Society of South Africa. Introduction. The family research enthusiast can follow various approaches , when they delve into family history. Some use a story line, for example the story of a ring, inherited by the latest in the line of daughters. She has the same names as the original ancestor, coming from the early 1800's of the previous millennium. A second approach may have history as departing point like the family-history of genl Jan Smuts, born in Riebeek-West in the Western Cape, to eventually become Chancellor of Cambridge, Prime Minister of South Africa, and member of the British War Cabinet during both the first and second World Wars(1914-1919) and (1939-45). It can also be looked at from a political perspective, for instance the relationship between the Smuts and Malan-families, both from Riebeek-West in the Western Cape, both becoming Prime Ministers of South-Africa. The location and family connection is a third possibility. Prof. Christiaan Neethling Barnard, famous doctor and professor from Groote Schuur Hospital, and the University of Cape Town, fitted into the genealogy of the de Swardt-family from Gwayang, George. In the fourth instance, it may have a church related bearing, for example the role that the de Swardt- family played in the Dutch Reformed Church in George from its establishment in 1813. Guillaume de Swardt (53 years) and his wife, Anna Sophia Weyers (39 years) were the first persons to be adopted in the church on 30 April 1813. -

Pretoria Moot

Pretoria Moot JANUARY 29, 2021 • www.rekordmoot.co.za • 012-842-0300 Visit our website for breaking Local police will help Mobile kiosks plan for School is next stage for local, national and international news. with gun amnesty 2 renewing licences 3 her after 19 operations 4 www.rekordmoot.co.za A R1,2-million ambulance with a special isolation chamber for patients with highly infectious diseases was bought at just the right time, the Tshwane metro emergency care metro says.y practitioners Jocelyn Johnson and Tshidiso Mhlanga. ‘‘ Photos: Ron Sibiya. xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxx xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxx Brave unit in fight against Covid-19 Sinesipho Schrieber onto the chassis. isolation chamber the medical “It has an isolation chamber practitioners can continue giving The procurement of a special equipped with a negative pressure treatment to them without easily R1.2-million ambulance, designed fi ltration system that fi ts on the being infected. to transport patients with highly stainless steel monobloc ambulance “Just like all other health workers infectious diseases, by the Tshwane stretcher. and other frontline workers, metro in August last year came at just “The negative pressure isolation paramedics work in an environment the right time. chamber allows the patient to be with an inherent risk of infection. The ambulance is equipped with a scanned in the chamber without “Our team of paramedics working special isolation chamber. exposing the radiology staff to on the special infectious unit It may not have been bought with infection such as Covid-19 and ambulance is trained and equipped Covid-19 in mind, but the metro without needing to decontaminate to handle medical emergencies believes that it has strengthened its the computerised tomography (CT) where suspected or known cases of response with the current wave of scanning suite.” infectious substances are involved,” Covid-19 cases hitting Tshwane. -

12 September 1991

C£C7 I Bringing Africa South Vol.2 No.379 SOc (GST Inc.) Quiet Quayle jets in on Airforce WINDHOEK: US vice-president Dan Quayle jetted The' vice-president did not make any 'conunents upon his vice-president's visit. into Windhoek last night for the start of a two-day visit arrival. Namibia is the fourth country on Quayle' s five-nation African to Namibia. Quayle, on his first visit to Namibia, is the most senior US trip, part of a tour marked by calls for deomcmtic and economic He was met at the International Airport by US Ambassador official to visit southern Africa. reforms. to Namibia Genta Hawkins Holmes, acting Namibian Prime Tomorrow, he is to hold talks with President SamNujoma on The US vice-president, who has been preaching capitalism on Minister Hifikepunye Pohomba, acting Foreign Affairs Minis US aid progranunes to Namibia. Afterwards, he will address the his trip, has already visited Cape Verde, Nigeria and Malawi, ter Hidipo Hamutenya and Chief of Protocol Martin Andj amba. media at State House, visit a Katutura School, and in the after where he spoke of the :'democmtic revolution spreading all Quayle is being accompanied by his wife, Marilyn, and a noon, head north to visit the Etosha National Park. around" the world and Africa. delegationheaded by US Health and Human Sciences Secretary Also among the welcoming party was President Bush's grand On Friday Quayle is scheduled to leave for the Ivory Coast. - Dr Louis Sullivan. son, J onathan, who was part ofthe advance team to prepare for the Sapa, Associated Press Tale of torture Arandis MBATJIUA NGAVIRUE THE three workers who claim they were tortured by police fights men at Arandis yesterday spoke out about their night marish experience. -

GROWING GLORIOUS ALOES Rhapsodies in Blue How to Be Resilient

June 2019 GROWING GLORIOUS ALOES Rhapsodies in Blue How to be Resilient Published in close co-operati on with the Fourways Gardens Home Owners Associati on Representing Extraordinary Homes for Sale & Rental in Fourways Gardens. For a FREE, no obligation valuation, contact your Fourways Gardens Specialist Fourways Gardens Specialist Contact us on 011 469 4950 | [email protected] Shop 11 Dainfern Square, Broadacres Drive, Dainfern Each office is independently owned and operated. June 2019 02 From the General Manager 04 Movie Night in the Park 06 Mother’s Day at the Clubhouse 08 Monthly Draw 10 Blinds on the Clubhouse Deck 12 FWG Charity Club 14 FWG Activity Providers 15 Another CathARTic Paint Night 16 FWG Gardening Club News 22 FWG Wine Club News 24 How to be Resilient 26 TheCarScene: Renault Duster 4X4 30 The Cavern Drakensberg Resort & Spa 32 Hyundai Santa Fe 35 James Clarke: Rhapsodies in Blue 37 Outdoor Feature 46 Gardens of Italy 49 Top 8 Travel Deals 53 Dainfern College: Playful Learning 56 Kyalami Schools: Health is a way of living! 58 Rules of Animal Behaviour for Humans 62 Approved Estate Agents 63 Restaurant Competition 64 Classi eds 68 Humour COVER IMAGE: Derek Campbell CONTENTS FOURWAYS GARDENS Residential Estate 4 Contact Numbers / Emergencies / Fault Reporting Estate Of ce 011 465 7731 Clubhouse 011 465 0937 Estate Security 24/7 Security Control Room 011 465 5466/5465/2302 011 467 2005/1400 Site Manager 071 224 6776 Assist Site Manager 071 222 7037 FWG Mobile Site Phone 076 200 5280 Representing Extraordinary Homes for Sale & Rental in Fourways Gardens.