Public-Private Partnership Infrastructure Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KSP 7 Lessons from Korea's Railway Development Strategies

Part - į [2011 Modularization of Korea’s Development Experience] Urban Railway Development Policy in Korea Contents Chapter 1. Background and Objectives of the Urban Railway Development 1 1. Construction of the Transportation Infrastructure for Economic Growth 1 2. Supply of Public Transportation Facilities in the Urban Areas 3 3. Support for the Development of New Cities 5 Chapter 2. History of the Urban Railway Development in South Korea 7 1. History of the Urban Railway Development in Seoul 7 2. History of the Urban Railway Development in Regional Cities 21 3. History of the Metropolitan Railway Development in the Greater Seoul Area 31 Chapter 3. Urban Railway Development Policies in South Korea 38 1. Governance of Urban Railway Development 38 2. Urban Railway Development Strategy of South Korea 45 3. The Governing Body and Its Role in the Urban Railway Development 58 4. Evolution of the Administrative Body Governing the Urban Railways 63 5. Evolution of the Laws on Urban Railways 67 Chapter 4. Financing of the Project and Analysis of the Barriers 71 1. Financing of Seoul's Urban Railway Projects 71 2. Financing of the Local Urban Railway Projects 77 3. Overcoming the Barriers 81 Chapter 5. Results of the Urban Railway Development and Implications for the Future Projects 88 1. Construction of a World-Class Urban Railway Infrastructure 88 2. Establishment of the Urban-railway- centered Transportation 92 3. Acquisition of the Advanced Urban Railway Technology Comparable to Those of the Developed Countries 99 4. Lessons and Implications -

Construction Supervision

SAMBO ENGINEERING Corporate Profile To the World, For the Future Construction engineering is basically having big change as periodic requirements from “The 4th Industrial Revolution”. SAMBO ENGINEERING is trying hard to change and innovate in order to satisfy clients and react actively to the change of engineering market. SAMBO ENGINEERING provides total solution for the entire process of engineering such as plan, design, CM/PM, O&M in roads, railways, civil structures, tunnels & underground space development, transportation infrastructure & environmental treatment, new & renewable energy, urban & architecture planning for land development, water and sewage resource. Recently, from natural disaster such as earthquakes and ground settlement, in order to create motivation for stable profit system, we adapt BIM, perform topographical survey using Drones, design automation using AI, underground safety impact assessment as well as active investment for new & renewable energy such as solar and wind power plant. We accumulate lots of technologies and experience from R&D participation which develops and applies new technology and patent as well as technical exchange with academies and technical cooperation with major globalized engineering companies. SAMBO ENGINEERING will be one of the leading engineering companies in the future by overcoming “The 4th Industrial Revolution”. Algeria - Bir Touta~Zeralda Railway Project Armenia - Project Management for South-North Expressway Project Azerbaijan - Feasibility Study for Agdas~Laki, Arbsu~Kudamir~Bahramtepe -

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War

RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War INCLUDING Lightning Canberra Harrier Vulcan www.keypublishing.com RARE IMAGES AND PERIOD CUTAWAYS ISSUE 38 £7.95 AA38_p1.indd 1 29/05/2018 18:15 Your favourite magazine is also available digitally. DOWNLOAD THE APP NOW FOR FREE. FREE APP In app issue £6.99 2 Months £5.99 Annual £29.99 SEARCH: Aviation Archive Read on your iPhone & iPad Android PC & Mac Blackberry kindle fi re Windows 10 SEARCH SEARCH ALSO FLYPAST AEROPLANE FREE APP AVAILABLE FOR FREE APP IN APP ISSUES £3.99 IN APP ISSUES £3.99 DOWNLOAD How it Works. Simply download the Aviation Archive app. Once you have the app, you will be able to download new or back issues for less than newsstand price! Don’t forget to register for your Pocketmags account. This will protect your purchase in the event of a damaged or lost device. It will also allow you to view your purchases on multiple platforms. PC, Mac & iTunes Windows 10 Available on PC, Mac, Blackberry, Windows 10 and kindle fire from Requirements for app: registered iTunes account on Apple iPhone,iPad or iPod Touch. Internet connection required for initial download. Published by Key Publishing Ltd. The entire contents of these titles are © copyright 2018. All rights reserved. App prices subject to change. 321/18 INTRODUCTION 3 RAF Centenary 100 Famous Aircraft Vol 3: Fighters and Bombers of the Cold War cramble! Scramble! The aircraft may change, but the ethos keeping world peace. The threat from the East never entirely dissipated remains the same. -

How Should Techno Parks Innovate to Support Start-Ups and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Effectively in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution?

https://doi.org/10.7165/wtr17a0829.16 OPEN ACCESS How Should Techno Parks Innovate to Support Start-ups and Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises Effectively in the Era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution? Inje Cho1, Eung-Hyun Lee2, Hoonje Cho3* 1 CEO of Actnerlab 2 Researcher of World Technopolis Association 3 Invited Professor of Chungnam National University Abstract In 1995, the Republic of Korea started to establish Techno Park (TP) in order to develop the regional industry while promoting the balanced development of the land. By 2008, 18TPs were established nationwide and have become cradles for developing local industries. And recently evolved forms of TP such as Daedeok Techno Valley and Pangyo Techno Valley emerged. In addition, 19 Centers for Creative Economy and Innovation (CCEI) were established nationwide and Tech-Incubator Program for start-ups (TIPS) was introduced to support and mentor start-ups. TPs in Korea become bureaucratic in course of time, and the new trial of innovation of TP is needed. In Korea, professional TIPS-accelerators mentoring and investing start-ups have a history of only five years. But they support and mentor start-ups efficiently, and have obtained good results. In this paper, we propose that TP attract TIPS-accelerators actively and collaborate with each other to support and mentor start-ups and SMEs effectively. Keywords Technopark, TIPS, Accelerator, Start-up and SMEs, Mentoring and nurturing Ⅰ. INTRODUCTION government’s dedication to the development of science and technology over the last 40 years. It is a powerful example of Developments in science and technology can have pro- how the growth of science and technology in a country is found effects on a country’s economic growth and employ- linked to its economic development. -

Operation Dominic I

OPERATION DOMINIC I United States Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Tests Nuclear Test Personnel Review Prepared by the Defense Nuclear Agency as Executive Agency for the Department of Defense HRE- 0 4 3 6 . .% I.., -., 5. ooument. Tbe t k oorreotsd oontraofor that tad oa the book aw ra-ready c I I i I 1 1 I 1 I 1 i I I i I I I i i t I REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NC I NA6OccOF 1 i Technical Report 7. AUTHOR(.) i L. Berkhouse, S.E. Davis, F.R. Gladeck, J.H. Hallowell, C.B. Jones, E.J. Martin, DNAOO1-79-C-0472 R.A. Miller, F.W. McMullan, M.J. Osborne I I 9. PERFORMING ORGAMIIATION NWE AN0 AODRCSS ID. PROGRAM ELEMENT PROJECT. TASU Kamn Tempo AREA & WOW UNIT'NUMSERS P.O. Drawer (816 State St.) QQ . Subtask U99QAXMK506-09 ; Santa Barbara, CA 93102 11. CONTROLLING OFClCC MAME AM0 ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE 1 nirpctor- . - - - Defense Nuclear Agency Washington, DC 20305 71, MONITORING AGENCY NAME AODRCSs(rfdIfI*mI ka CamlIlIU Olllc.) IS. SECURITY CLASS. (-1 ah -*) J Unclassified SCHCDULC 1 i 1 I 1 IO. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES This work was sponsored by the Defense Nuclear Agency under RDT&E RMSS 1 Code 6350079464 U99QAXMK506-09 H2590D. For sale by the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 19. KEY WOROS (Cmlmm a nm.. mid. I1 n.c...-7 .nd Id.nllh 4 bled nlrmk) I Nuclear Testing Polaris KINGFISH Nuclear Test Personnel Review (NTPR) FISHBOWL TIGHTROPE DOMINIC Phase I Christmas Island CHECKMATE 1 Johnston Island STARFISH SWORDFISH ASROC BLUEGILL (Continued) D. -

Table of Contents >

< TABLE OF CONTENTS > 1. Greetings .................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Company Profile ........................................................................................................................................................................ 3 A. Overview ........................................................................................................................................................................... 3 B. Status of Registration ........................................................................................................................................................ 6 3. Organization .............................................................................................................................................................................. 8 A. Organization chart ............................................................................................................................................................. 8 B. Analysis of Engineers ........................................................................................................................................................ 9 C. List of Professional Engineers......................................................................................................................................... 10 D. Professional Engineer in Civil Eng.(U.S.A) .................................................................................................................. -

The Beginning of a Better Future

THE BEGINNING OF A BETTER FUTURE Doosan E&C CONTENTS Doosan Engineering & PORTFOLIO BUSINESS 04 CEO Message Construction COMPANY PROFILE 06 Company Profile 08 Corporate History 12 Socially Responsible Management 16 Doosan Group BUSINESS PORTFOLIO HOUSING 22 Brand Story 28 Key Projects 34 Major Project Achievements Building a better tomorrow today, the origin of a better world. ARCHITECTURE 38 Featured Project 40 Key Projects Doosan Engineering & Construction pays keen attention 48 Major Project Achievements to people working and living in spaces we create. We ensure all spaces we create are safer and more INFRASTRUCTURE pleasant for all, and constantly change and innovate 52 Featured Project to create new value of spaces. 54 Key Projects 60 Major Project Achievements This brochure is available in PDF format which can be downloaded at 63 About This Brochure www.doosanenc.com CEO MESSAGE Since the founding in 1960, Doosan Engineering & Construction (Doosan E&C) has been developing capabilities, completing many projects which have become milestones in the history of the Korean construction industry. As a result, we are leading urban renewal projects, such as housing redevelopment and reconstruction projects, supported by the brand power of “We’ve”, which is one of the most prominent housing brands in Korea. We also have been building a good reputation in development projects, creating ultra- large buildings both in the center of major cities including the Seoul metropolitan area. In particular, we successfully completed the construction of the “Haeundae Doosan We’ve the Zenith”, an 80-floor mixed-use building 300-meter high, and the “Gimhae Centum Doosan We’ve the Zenith”, an ultra-large residential complex for 3,435 households, demonstrating, once again, Doosan E&C’s technological prowess. -

BUSAN (International) Incheon Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic)

Transportation Information For Participants BUSAN (International) Incheon Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic) If you arrive at Incheon airport Distance : 430km Incheon Airport from your country with Time : 1hr Incheon international flight, the easiest Airport way to go to Busan is taking a direct flight (domestic) to Gimhae airport from Incheon airport. 1hr * Passengers of domestic flights should check in at counter “A” which is the domestic flight There are more than 20 flights only check-in counter. After checking in, the passenger should enter the boarding area directly heading to Gimhae airport Gimhae Airport through the domestic departure gate. from Incheon airport everyday. Passengers should be at the boarding gate 40 Click here to see the flight schedule. minutes prior to the boarding time. http://www.airport.kr/pa/en/d/1/2/1/index.jsp Fare: Approx. KRW 70,000 (Approx. USD 61). (The fare can vary depending on the time of booking.) (International) Incheon Airport → (AREX) → Gimpo Airport (Domestic) → → Gimhae Airport (Domestic) Gimpo Airport After arriving at Incheon airport, Distance : 450km you can go to Gimpo airport to Time : 1.5hr Gimpo take a direct domestic flight to Incheon Airport Airport Gimhae airport. There are 2 ways to go to Gimpo 30mins airport from Incheon airport: AREX or airport limousine There are more than 25 flights directly Incheon Airport 1hr heading to Gimhae airport from Gimpo airport everyday. Click here to see the flight schedule. Gimhae https://goo.gl/SJ1tTx AREX Airport Fare: Approx. KRW 70,000 (Approx. USD 61) (The fare can vary depending on the time of booking.) AREX (Airport Railroad Train) station is on B1 floor The ticket office for limousine buses heading to Gimpo of Incheon airport. -

Great Britain's Relationship with the United States Has Long

ThYounge Origins of Anglo-American Nuclear Strike Planning A Most Special Relationship The Origins of Anglo-American Nuclear Strike Planning ✣ Ken Young Great Britain’s relationship with the United States has long been described as “special,” though whether this characterization is fair or meaningful remains a subject of heated debate.1 For John Charmley, the rela- tionship “had its uses, but for many years...hadbeen more useful to the Americans than it had to the British.”2 Henry Kissinger echoed this judg- ment, acknowledging that “the relationship was not particularly special in my day” but that Britain was important to the United States because “it made it- self so useful.”3 The idea of a special relationship seems a distinctively Churchillian conception, a mythic invocation of a common interest to which Harold Macmillan was happy to subscribe. Both of these British prime minis- ters, of course, had American mothers. Waning (during Edward Heath’s pre- miership) and waxing again (during Margaret Thatcher’s and Tony Blair’s times in ofªce), the special relationship is something that continues to be expressed in the politics of gesture, sentiment, and self-ascribed historic missions. Politicians employ rhetoric, whereas diplomats are more at home with practicalities. Oliver Franks, writing in 1990 about his service as British am- 1. Jeffrey D. McCausland and Douglas T. Stuart, eds., US-UK Relations at the Start of the 21st Century (Carlisle Barracks, PA: Strategic Studies Institute, U.S. Army War College, 2006). More generally, the transatlantic relationship nowadays “is interesting again; and not just to academics and politicians, but onthestreetaswell....[It]isnolonger to be taken for granted. -

Global Report Global Metro Projects 2020.Qxp

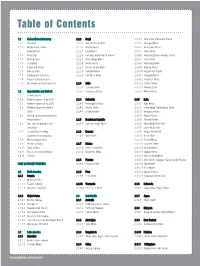

Table of Contents 1.1 Global Metrorail industry 2.2.2 Brazil 2.3.4.2 Changchun Urban Rail Transit 1.1.1 Overview 2.2.2.1 Belo Horizonte Metro 2.3.4.3 Chengdu Metro 1.1.2 Network and Station 2.2.2.2 Brasília Metro 2.3.4.4 Guangzhou Metro Development 2.2.2.3 Cariri Metro 2.3.4.5 Hefei Metro 1.1.3 Ridership 2.2.2.4 Fortaleza Rapid Transit Project 2.3.4.6 Hong Kong Mass Railway Transit 1.1.3 Rolling stock 2.2.2.5 Porto Alegre Metro 2.3.4.7 Jinan Metro 1.1.4 Signalling 2.2.2.6 Recife Metro 2.3.4.8 Nanchang Metro 1.1.5 Power and Tracks 2.2.2.7 Rio de Janeiro Metro 2.3.4.9 Nanjing Metro 1.1.6 Fare systems 2.2.2.8 Salvador Metro 2.3.4.10 Ningbo Rail Transit 1.1.7 Funding and financing 2.2.2.9 São Paulo Metro 2.3.4.11 Shanghai Metro 1.1.8 Project delivery models 2.3.4.12 Shenzhen Metro 1.1.9 Key trends and developments 2.2.3 Chile 2.3.4.13 Suzhou Metro 2.2.3.1 Santiago Metro 2.3.4.14 Ürümqi Metro 1.2 Opportunities and Outlook 2.2.3.2 Valparaiso Metro 2.3.4.15 Wuhan Metro 1.2.1 Growth drivers 1.2.2 Network expansion by 2025 2.2.4 Colombia 2.3.5 India 1.2.3 Network expansion by 2030 2.2.4.1 Barranquilla Metro 2.3.5.1 Agra Metro 1.2.4 Network expansion beyond 2.2.4.2 Bogotá Metro 2.3.5.2 Ahmedabad-Gandhinagar Metro 2030 2.2.4.3 Medellín Metro 2.3.5.3 Bengaluru Metro 1.2.5 Rolling stock procurement and 2.3.5.4 Bhopal Metro refurbishment 2.2.5 Dominican Republic 2.3.5.5 Chennai Metro 1.2.6 Fare system upgrades and 2.2.5.1 Santo Domingo Metro 2.3.5.6 Hyderabad Metro Rail innovation 2.3.5.7 Jaipur Metro Rail 1.2.7 Signalling technology 2.2.6 Ecuador -

Governing the Bomb: Civilian Control and Democratic

DCAF GOVERNING THE BOMB Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons edited by hans born, bates gill and heiner hänggi Governing the Bomb Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons STOCKHOLM INTERNATIONAL PEACE RESEARCH INSTITUTE SIPRI is an independent international institute dedicated to research into conflict, armaments, arms control and disarmament. Established in 1966, SIPRI provides data, analysis and recommendations, based on open sources, to policymakers, researchers, media and the interested public. The Governing Board is not responsible for the views expressed in the publications of the Institute. GOVERNING BOARD Göran Lennmarker, Chairman (Sweden) Dr Dewi Fortuna Anwar (Indonesia) Dr Alexei G. Arbatov (Russia) Ambassador Lakhdar Brahimi (Algeria) Jayantha Dhanapala (Sri Lanka) Dr Nabil Elaraby (Egypt) Ambassador Wolfgang Ischinger (Germany) Professor Mary Kaldor (United Kingdom) The Director DIRECTOR Dr Bates Gill (United States) Signalistgatan 9 SE-169 70 Solna, Sweden Telephone: +46 8 655 97 00 Fax: +46 8 655 97 33 Email: [email protected] Internet: www.sipri.org Governing the Bomb Civilian Control and Democratic Accountability of Nuclear Weapons EDITED BY HANS BORN, BATES GILL AND HEINER HÄNGGI OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 2010 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford OX2 6DP Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York © SIPRI 2010 All rights reserved. -

Nippon Signal Report 2019 Report Signal Nippon

NIPPON SIGNAL REPORT 2019 NIPPON SIGNAL REPORT 2019 NIPPON SIGNAL GROUP PHILOSOPHY Our Mission Our Values Our Code of Conduct: We help realize a more secure and comfort- 1. Emphasize “safety and reliability” above all. Six Commitments … (Manufacturing) able society through superior technologies Mono-zukuri 1. Working for Customers’ Kando that provide safety and reliability. 2. Strive to improve customer value by taking the 2. Fair Corporate Activities Our Mission customer’s perspective. 3. Proper Information Disclosure and … (Business) Koto-zukuri Communication with Society Our Vision 3. Take on challenges for your own growth. 4. Respect for Human Rights and Creation of a … Our Vision We strive to become a global company by Hito-zukuri (Education) Good Working Environment pursuing world-leading technologies with 4. Preserve the environment and contribute to the 5. Environmental Protection and Proactive Social ingenuity and passion to inspire our development of local communities. Contribution Activities … Machi-zukuri (CSR) Our Values customers’ Kando.* 6. Proper Management of Company Assets 5. Have dreams and share them. and Information * Kando is a Japanese word that describes the sense of awe and the emo- tion you feel when experiencing something beautiful and amazing for … Michi-zukuri (Creation of the future) the first time. It is the moment when your expectations are exceeded— Our Code of Conduct you feel Kando. CONTENTS Section 1 Section 2 Section 3 Editorial Policy Vision of the Nippon Signal Group Management Strategy Data Section Note on Forward-Looking Statements The Nippon Signal Group publishes annual inte- Nippon Signal Report 2019 contains grated reports (Nippon Signal reports) for its custom- for Value Creation statements on the future plans, forecasts, ers, shareholders, investors, and other stakeholders and prospects of the Nippon Signal Group.