Danbury Branch Improvement Program Task 5

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Press Releases Gov. Malloy, CTDOT Indefinitely Postpone Hundreds Of

Press Releases 01/10/2018 Gov. Malloy, CTDOT Indefinitely Postpone Hundreds of Transportation Projects Across Connecticut Malloy Administration Will Work With Legislature to Identify New Funding and Save Projects (HARTFORD, CT) – Governor Dannel P. Malloy and Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT) Commissioner James P. Redeker today released a full list of projects totaling $4.3 billion that are postponed indefinitely until new revenue is appropriated for the Special Transportation Fund (STF). The Governor made clear that his administration will announce detailed proposals this month that, if adopted by the General Assembly, would bring the projects back online. The STF finances the state’s transportation system, including the operating costs of the CTDOT and all of the services it provides. Last month, Governor Malloy reiterated and increased his warnings on the solvency of the fund following the release of a report showing that without prompt action, the STF will be in deficit by fiscal year 2019, which begins July 1, 2018. **Download the list of CTDOT projects now postponed indefinitely here** Hundreds of projects across the state, such as critical improvements to the I-91/Route 15 interchange on the Charter Oak Bridge, the replacement of the Waterbury Mixmaster, and the widening of I-95 from Bridgeport to Stamford, are postponed indefinitely, or until resources are identified to allow projects to continue. Even routine highway maintenance and transportation aid to cities and towns are seriously jeopardized. “If Connecticut does not take the necessary action to allow us to restart these vital projects, not only will it put the state’s infrastructure into a further state of disrepair, it will hurt our economy,” Governor Malloy said. -

AQUIFERPROTECTIONAREA SW Estport , CONNECTICUT

n M ! R F S o N G o Godfrey Pond C e t Inwood Rd u P u n o d a r u d B W d r n n r t e R L r e t d R d b e r t e R o t t s n R 111 D i l n I o a e l a r o M o t e n l s S1 r R i t t V W w l r A O d n k a l d e K i i R e i S d 1 n M a n n l R W B e l y D H o id g e a a T u a l R t R i Wheelers Pond 1 H L l a a r x d n l B o a g e R d r r a v a d o F d d e d d R n r T t e Nod Hill Pond t e y n l n e R r e R R W d h d o e u d r D e D d i y n u D R v M R e e E w e e d n k d e o S H R u b n d w r r a r r r e Chestnut Hill r c d e o e d d w 7 R H u w o n b L e r D d l R d Mill River h B o d L w t S W n d b n s s s u Plymouth Avenue Pond £ a d s y e ¤ r A u o i R R s o n i b Pipers t o R h d Hill R n d o i n L c S d d e 5 C t a e d r r d d B o U H g Powells Hill k t t o r t 9 d e S k n Spruc u p r l d D o R d c r R R L P e S i a r n s l H r Cristina R 136 i h L Ln e n B l i r T R o d n r d s l L S o n r R V e o H o k L R i r M d t M Killian A H G L a S ve d R e s R y n l g e d Pin 1 i l C r a d w r n M e d d e r a a 1 i R r d c y e D h k h s r S R 1 d o d c E Cricker Brook i t c a k n l 7 r M d r u w a e l o R l n y g a R d r S n d l Dr c e B W od l e F nwo d r Nature Pond o t utt o l S i B t w d C h l S B n y i d r o t l e W ch R e i D R e e o o D p B r M Hill Rd i L d n r H R ey l on r il H P H n L H o ls illa w o d v r w t w a w on La n o s D D d d e O e S e n w r g r R e p i e i W k l n n e d d W t r g L e v e r t l y e l D l r y g l 53 e e T a e o R e l s d y d H n Plum rkw o a D i P a R n l r a S d R L V W i w o u r u Jennings Brook l -

Transit Oriented Development Final Report | September 2010

FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration FTA ALTERNATIVES ANALYSIS DRAFT/FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT DANBURY BRANCH IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM TRANSIT ORIENTED DEVELOPMENT FINAL REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2010 In Cooperation with U.S. Department CONNECTICUT South Western Regional Planning Agency of Transportation DEPARTMENT OF Federal Transit TRANSPORTATION Administration Abstract This report presents an evaluation of transit-oriented development (TOD) opportunities within the Danbury Branch study corridor as a component of the Federal Transit Administration Alternatives Analysis/ Draft Environmental Impact Statement (FTA AA/DEIS) prepared for the Connecticut Department of Transportation (CTDOT). This report is intended as a tool for municipalities to use as they move forward with their TOD efforts. The report identifies the range of TOD opportunities at station areas within the corridor that could result from improvements to the Danbury Branch. By also providing information regarding FTA guidelines and TOD best practices, this report serves as a reference and a guide for future TOD efforts in the Danbury Branch study corridor. Specifically, this report presents a definition of TOD and the elements of TOD that are relevant to the Danbury Branch. It also presents a summary of FTA Guidance regarding TOD and includes case studies of FTA-funded projects that have been rated with respect to their livability, land use, and economic development components. Additionally, the report examines commuter rail projects both in and out of Connecticut that are considered to have applications that may be relevant to the Danbury Branch. -

Financial Analyses Included Herein Present the Operating Revenues and Expenses Only for Those Properties Governed by the State Lease Agreements

SSSeeewwwaaarrrddd aaannnddd Monde CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS RAIL GOVERNANCE STUDY Task 4.3 – Financial Review Connecticut Department of Transportation Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ........... ............... ............... ......................... ............... 1 - 3 OVERVIEW OF ALL STATIONS ............... ............... ......................... ............... 4 - 8 STATION COMPARISON ANALYSIS Five Year Totals ............... ............... ......................... ............... 9 Year end June 30, 1996 ............... ............... ......................... ............... 10 Year end June 30, 1997 ............... ............... ......................... ............... 11 Year end June 30, 1998 ............... ............... ......................... ............... 12 Year end June 30, 1999 ............... ............... ......................... ............... 13 Year end June 30, 2000 ............... ............... ......................... ............... 14 STATIONS - NEW HAVEN LINE Main Line New Haven Finances ........... ............... ............... ......................... ............... 15 - 19 Station and Parking Operations Profit (Loss) - 1996--2000 ............... 20 - 22 Milford Finances ........... ............... ............... ......................... ............... 23 - 25 Station and Parking Operations Profit (Loss) - 1996--2000 ............... 26 - 28 Stratford Finances ........... ............... ............... ......................... ............... 29 - 31 Station and Parking -

A Q U I F E R P R O T E C T I O N a R E a S N O R W a L K , C O N N E C T I C

!n !n S c Skunk Pond Beaver Brook Davidge Brook e d d k h P O H R R O F p S o i d t n n l c t u i l R a T S d o i ll l t e e lv i d o t R r r d r l h t l l a H r n l t r M b a s b R d H e G L R o r re R B C o o u l e t p o n D o e f L i s Weston Intermediate School y l o s L d r t e Huckleberry Hills Brook e t d W d r e g Upper Stony Brook Pond N L D g i b R o s n Ridgefield Pond a t v d id e g e H r i l Country Club Pond b e a R d r r S n n d a g e L o n tin a d ! R d l H B n t x H e W Still Pond d t n Comstock Knoll u d a R S o C R k R e L H d i p d S n a l l F tt h Town Pond d l T te r D o e t l e s a t u e L e c P n n b a n l R g n i L t m fo D b k H r it to Lower Stony Brook Pond o r A d t P n d s H t F u d g L d d i Harrisons Brook R h e k t R r a e R m D l S S e e G E o n y r f ll H rt R r b i i o e n s l t ld d d o r l ib l a e r R d L r O e H w i Fanton Hill g r l Cider Mill School P y R n a ll F i e s w L R y 136 e a B i M e C H k A s t n d o i S d V l n 3 c k r l t g n n a d R i u g d o r a L 3 ! a l r u p d R d e c L S o s e Hurlbutt Elementary School R d n n d D A i K w T n d o O n D t f R l g d R l t ad L i r e R e e r n d L a S i m a o f g n n n D d n R o t h n Middlebrook School ! l n t w Lo t a 33 i n l n i r E id d D w l i o o W l r N e S a d l e P g n V n a h L C r L o N a r N a S e n e t l e b n l e C s h f ! d L nd g o a F i i M e l k rie r id F C a F r w n P t e r C ld l O e r a l y v f e u e o O n e o a P i O i s R w e t n a e l a n T t b s l d l N l k n t g i d u o e a o R W R Hasen Pond n r r n M W B y t Strong -

Drmnsmay-July2013

The Railyard Local Volume 12, Issue 3 -The Monthly Newsletter of the Danbury Railway Museum- May‐July 2013 DRM at GCT’s Grand In This Issue ~ Upcoming Events at DRM ‐ Page 2 Centennial Parade of Trains ~ Words from Our President ‐ Page 4 Huge crowds come to see famous and ~ Board of Directors News ‐ Page 5 historic railcars on display Plus . Ten Years Ago and New Members Danbury Railway Museum was honored to have five pieces of its rolling stock chosen to be dis‐ Burro Crane Revival played at Grand Central Terminal’s 100th anniversary Part 1 Introduction “Parade of Trains” the weekend of May 11th & 12th. The By Michael Madyda, Project Manager Metropolitan After itʹs arrival in October 1995, our 1947 Transportation Model 30 Burro crane CB3004 had sat unrestored and Authority hand‐picked inoperable. A couple of unsuccessful attempts had the Tonawanda Valley been made in the past to restore it. For those of you Pullman Co. observa‐ who remember, CB3004 came with a counterpart, tion car, the PRR Class CB3001, that was supposed to provide parts for the BNM‐70 Baggage/ restoration of CB3004. Several years ago, a decision Railway Post Office was made to scrap CB3001 when the yard was being car, the 1171 ACMU, cleaned up. Unfortunately, vital parts from CB3004 the NYC 2013 EMD that were removed, but not replaced, for its restoration FL‐9 diesel electric were lost or scrapped during that time. locomotive, and the CDOT 605 ALCO RS‐ A sign welcomes visitors. 3m diesel to be trans‐ Top photo: Carolyn Taylor ported and displayed Bottom photo: Bob Boothe at the event. -

Branchville Individual Station Report

BRANCHVILLE TRAIN STATION VISUAL INSPECTION REPORT January 2007 Prepared by the Bureau of Public Transportation Connecticut Department of Transportation Branchville Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Overview: The Branchville Train Station is located on Route 7 in the southeast corner of Ridgefield. It is relatively easy to find, although a station sign is needed at each of the two entrances. Vehicular access is provided over two river bridges in varied stages of disrepair. The station is nestled between the Norwalk River, the railroad tracks, Depot Road and Portland Avenue. The station building houses a bakery and gift shop. New sidewalk and black railing separate the full parking lot from the tracks. An awning provides some shelter for patrons of the bakery or waiting commuters. The area is neat, likely from the housekeeping efforts of bakery personnel. A high-level platform with stairs and a ramp provides access to the rail cars. The platform has a full-length canopy and benches. Maintenance Responsibilities: Owner: State Operator: Town Platform Lights: Metro-North Trash: Metro-North Snow Removal: Town Shelter Glazing: Town Platform Canopy: Town Platform Structure: Town Parking: Town Page 2 Branchville Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Station Layout: Aerial Photo by Aero-Metric, Inc. – Graphics by Urbitran as part of the Rail Governance Study Station Building State-Owned Parking Area Page 3 Branchville Train Station Visual Inspection Report January 2007 Train Station Visual Inspection Parameters: The Connecticut Department of Transportation (Department) recently inspected all 36 New Haven Line train stations to assess their appearance, safety, means of access and overall condition. -

Upcoming Railyard Projects Semaphore Almost Ready to Send Signals Again DRM Dressed up for Easter Museum Forging Ahead with Blac

The Railyard Local Volume 4, Issue 5 -The Monthly Newsletter of the Danbury Railway Museum- May 2005 Museum Forging Ahead with In This Issue Blacksmithing Event ~What’s Happening at the DRM - page 4 ~Strap Rail - page 5 st nd Hammer-In on May 21 and 22 ~Boston&Maine #1455 articles - page 6 Come join us at our vintage forge, the site of plus . our first annual blacksmithing event! This is an excit- Gift Shop and Membership Updates ing chance to observe reknowned blacksmiths show- ing the techniques involved in creating works in iron. DRM Dressed Up for Easter They will be selling some of their wares. G-scale model trains will be running on a special layout. The Danbury Railway Museum was in its th th Refreshments will be available. The DRM Library will Easter best for the weekend of March 19 -20 and on th th be conducting a sale, as described in the Library News the 25 &-26 to greet the parade of visitors. Special on page 2. Our gift shop already has books on black- decorations abounded inside the Museum building, smithing (see railyard and cars. Our Budd car took a rail trip to the page 2). All this center platform for a visit to the Easter Bunny in the will be in addi- bright red CN caboose, which featured colorful trim- tion to our reg- ular weekend train opera- tions. These attractions will make for a fun- filled weekend! Continued on page 7 Semaphore Almost Ready to Send Signals Again During the past A carload of Budd car passengers enters the CN caboose to few weeks the Wilton greet the Easter Bunny within. -

Happy Visitors at Santa Event Retired Railroader's Oral History Documented at DRM Maybrook Yard Ledgers Reminder: Resume Deadl

The Railyard Local Volume 5, Issue 1 -The Monthly Newsletter of the Danbury Railway Museum- January 2006 Happy Visitors at Santa Event In This Issue DRM Welcomes Guests from Several States ~DRM Express Track - page 3 The atmosphere at the Danbury Railway ~RPO New and Notes - page 4 Museum has been filled with extra energy and excite- ~The Yards Inside - page 6 ment during the past couple of weekends. This is due plus . to the increasingly popular Santa Event being held on Gift Shop and New Members three weekends this month. It features a ride aboard a vintage train within the railyard. A red caboose deco- rated with holiday lights revolves on the turntable. Mr. Retired Railroader’s Oral Frosty leads disembarking passengers to Santa’s Special Railroad Car, where Santa, Mrs. Santa, and History Documented at DRM elves are surrounded by decorations. Photo opportuni- On November 14, 2005, 92-year old Loyd ties for pictures with Santa have been available. Each MacNayr, a former Boston & Maine Railroad fireman child has and engineer, journeyed with his family from East received a Longmeadow, MA to the Danbury Railway Museum small gift. Even to participate in an oral history video taping. Loyd more than in and his family were greeted at the Museum at around previous years, 10am by Bob Boothe, Dan Foley, Rich Edwards, Mike the Museum Salata, Peter McLachlan, and Steve Gould. Taping was building and done in two locations: next to the fireplace in the railyard Museum, and next to and on 2-6-0 #1455 in the rail abounds with yard. -

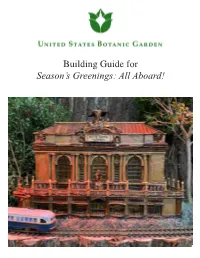

Train Station Models Building Guide 2018

Building Guide for Season’s Greenings: All Aboard! 1 Index of buildings and dioramas Biltmore Depot North Carolina Page 3 Metro-North Cannondale Station Connecticut Page 4 Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal New Jersey Page 5 Chattanooga Train Shed Tennessee Page 6 Cincinnati Union Terminal Ohio Page 7 Citrus Groves Florida Page 8 Dino Depot -- Page 9 East Glacier Park Station Montana Page 10 Ellicott City Station Maryland Page 11 Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station Pennsylvania Page 12 Grain Elevator Minnesota Page 13 Grain Fields Kansas Page 14 Grand Canyon Depot Arizona Page 15 Grand Central Terminal New York Page 16 Kirkwood Missouri Pacific Depot Missouri Page 17 Lahaina Station Hawaii Page 18 Los Angeles Union Station California Page 19 Michigan Central Station Michigan Page 20 North Bennington Depot Vermont Page 21 North Pole Village -- Page 22 Peanut Farms Alabama Page 23 Pennsylvania Station (interior) New York Page 24 Pikes Peak Cog Railway Colorado Page 25 Point of Rocks Station Maryland Page 26 Salt Lake City Union Pacific Depot Utah Page 27 Santa Fe Depot California Page 28 Santa Fe Depot Oklahoma Page 29 Union Station Washington Page 30 Union Station D.C. Page 31 Viaduct Hotel Maryland Page 32 Vicksburg Railroad Barge Mississippi Page 33 2 Biltmore Depot Asheville, North Carolina built 1896 Building Materials Roof: pine bark Facade: bark Door: birch bark, willow, saltcedar Windows: willow, saltcedar Corbels: hollowed log Porch tread: cedar Trim: ash bark, willow, eucalyptus, woody pear fruit, bamboo, reed, hickory nut Lettering: grapevine Chimneys: jequitiba fruit, Kielmeyera fruit, Schima fruit, acorn cap credit: Village Wayside Bar & Grille Wayside Village credit: Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, one of the premier architects in American history, the Biltmore Depot was commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt III. -

Little Engine That Could Event Danbury Railway Day and Annual

The Railyard Local Volume 7, Issue 7 -The Monthly Newsletter of the Danbury Railway Museum- July 2008 Little Engine That Could Event In This Issue Museum hosts event for 3rd time ~ Ten Years Ago - Page 2 Once again our volunteers turned out to assist ~DRM Express Track - Page 3 in the many ways needed to conduct this special event ~ Images from The Little Engine That Could - Page 4 on the weekends of June 21-22 and 28-29. Thank you! ~ Historical Photos from 1939 - Page 6 It was clear from feedback from our guests and our plus . observations, that those attending this event thorough- A Valued Volunteer, and Al Kellogg Honored ly enjoyed all the special attractions accompanying it, Danbury Railway Day as well as our usual Museum and railyard displays. and Annual Member Picnic Double treat on Saturday, August 9th The focus of this 2nd annual Danbury Railway Day will be the celebration of the restoration of our Pennsylvania Railroad Railway Post Office car. Dr. Frank Schneer or the Railway Mail Service Library in Boyce, VA will speak at the dedication ceremony for the car, and there will be a special stamp cancellation We were disappointed in the ticket sales, which were lower than in the two previous years when we held this event. The final figures have not been tabu- by the United States Post Office right in our RPO car!. lated yet. The Events Committee once again worked to Of course, the car will be open for tours. We again will cut our overhead in advance of the event. -

RIDGEBURY CORPORATE CENTER 44 Old Ridgebury Road – Danbury, Connecticut 06810

RIDGEBURY CORPORATE CENTER 44 Old Ridgebury Road – Danbury, Connecticut 06810 - FOR LEASE : OFFICE SPACE - Todd E. Payne, SIOR 7 Old Sherman Turnpike, Suite 207 President Danbury, CT 06810 (203) 456-3223 203-744-7025 [email protected] Goodfellows.com RIDGEBURY CORPORATE CENTER 44 Old Ridgebury Road – Danbury, Connecticut 06810 PROPERTY INFORMATION / Executive Summary OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY OVERVIEW Available SF: 6,610 – 12,081 SF 44 Old Ridgebury Road, is a 130,000 SF office complex located in one of Danbury's premier west side locations. This corporate campus-style site with manicured Lease Rate: $22.00 SF/YR. grounds over looks a peaceful pond for a serene work (Gross) setting. Lot Size: 8 Acres LOCATION OVERVIEW PREMIER Class A Office Building, located off Exit 2 Year Built: 1988 on 1-84 near Route 7 and the Danbury Fair Mall. Ridgebury Corporate Center is within close proximity to New York state, Waterbury and the Building Size: 134,805 SF Hartford Metro Regions. Closest commuter rail station: Danbury Station Commuter Rail (New Haven Line): 5.6 miles Brewster Station Commuter Zoning: IL-40 Rail (Harlem Line): 6.8 miles Closest airports: Westchester County Airport: 30.6 miles Stewart International Airport: 43.7 miles RIDGEBURY CORPORATE CENTER 44 Old Ridgebury Road – Danbury, Connecticut 06810 PROPERTY INFORMATION / Property Highlights Property Highlights: ▪ Turn-Key Tenant buildout for five year leases. ▪ Full service cafeteria. ▪ On-site management. ▪ Conference Center. ▪ Outdoor cafe seating. RIDGEBURY CORPORATE CENTER 44 Old