Canada's Legal Pasts: Looking Forward, Looking Back

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Referral for Kidney Transplantation in Canadian Provinces

CLINICAL EPIDEMIOLOGY www.jasn.org Referral for Kidney Transplantation in Canadian Provinces S. Joseph Kim,1,a John S. Gill,2,3,a Greg Knoll,4,5 Patricia Campbell,6 Marcelo Cantarovich,7 Edward Cole ,1 and Bryce Kiberd8 1University Health Network, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada; 2University of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada; 3Division of Nephrology, Center for Health Evaluation and Outcome Sciences, Vancouver, Canada; 4University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; 5Department of Medicine, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Canada; 6University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; 7McGill University, Montreal, Canada; and 8Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada ABSTRACT Background Patient referral to a transplant facility, a prerequisite for dialysis-treated patients to access kidney transplantation in Canada, is a subjective process that is not recorded in national dialysis or trans- plant registries. Patients who may benefit from transplant may not be referred. Methods In this observational study, we prospectively identified referrals for kidney transplant in adult patients between June 2010 and May 2013 in 12 transplant centers, and linked these data to information on incident dialysis patients in a national registry. Results Among 13,184 patients initiating chronic dialysis, the cumulative incidence of referral for trans- plant was 17.3%, 24.0%, and 26.8% at 1, 2, and 3 years after dialysis initiation, respectively; the rate of transplant referral was 15.8 per 100 patient-years (95% confidence interval, 15.1 to 16.4). Transplant re- ferral varied more than three-fold between provinces, but it was not associated with the rate of deceased organ donation or median waiting time for transplant in individual provinces. -

The 1711 Expedition to Quebec: Politics and the Limitations

THE 1711 EXPEDITION TO QUEBEC: POLITICS AND THE LIMITATIONS OF GLOBAL STRATEGY IN THE REIGN OF QUEEN ANNE ADAM JAMES LYONS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of History School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham December 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT To mark the 300th anniversary of the event in question, this thesis analyses the first British attempt to conquer the French colonial city of Quebec. The expedition was a product of the turbulent political environment that was evident towards the end of the reign of Queen Anne. Its failure has consequently proven to be detrimental to the reputations of the expedition‘s commanders, in particular Rear-Admiral Sir Hovenden Walker who was actually a competent and effective naval officer. True blame should lie with his political master, Secretary of State Henry St John, who ensured the expedition‘s failure by maintaining absolute control over it because of his obsession with keeping its objective a secret. -

A History of the German Immigration to New York in 1710

5clr\oe.pperle A H»«!)torvOf The Qxrman Immiqration To lNi«vM YorK In \X\0 1 A HISTORY OF THE GERMAN IMMIGRATION TO NEW YORK IN 1710 BY HELEN KATHERINE SCHOEPPERLE A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 1^1^ I o CM UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Katherine Schoepperle ENTITLED A History of the German Iinmigration to mew York in 17L0 BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in History In Charge of Major Work Head of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination . A HIoTORY O'F^ THE GRmiMI IMP.TIGRATION TO NSW YORK IN 1710. IntroduG tion • The ';7ar of the Spanish .'^Ticcession and Gonditions in England at the beginning of the 18th Century, I, The iilmigrat ion from the Rhine Country. 1. Niimhers. 2. Duration and efforts to check emigration. 3, Territory from which the emigrants c *.me 4, Character. II. Conditions 'J^hich were Conducive to Emigration. 1. Social and economic. 2, Religious. III. Special inducements to Emigration. 1. Kocherthal's Party, 2. Kocherthal's Boarjk: with Letter. 3. Other literature . 4. The spread of Literature. 5. The activity of agents. 6. The 'v^'hig principles of government, and the IJatural- ization Act, 17. The Germans in England. 1. Reception and treatment. 2. The attemot to settle them in iiJngland. -

Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline Arthur G

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine History Documents Special Collections 1922 Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline Arthur G. Doughty Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory Part of the History Commons Repository Citation Doughty, Arthur G., "Acadian Exiles: a Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline" (1922). Maine History Documents. 27. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/mainehistory/27 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine History Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRONICLES OF CANADA Edited by George M. Wrong and H. H. Langton In thirty-two volumes 9 THE ACADIAN EXILE BY ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY Part III The English Invasion IN THE PARISHCHURCH AT GRAND PRE, 1755 From a colour drawing by C.W. Jefferys THE ACADIAN EXILES A Chronicle of the Land of Evangeline BY ARTHUR G. DOUGHTY TORONTO GLASGOW, BROOK & COMPANY 1922 Copyright in all Countries subscribing to the Berne Conrention TO LADY BORDEN WHOSE RECOLLECTIONS OF THE LAND OF EVANGELINE WILL ALWAYS BE VERY DEAR CONTENTS Paee I. THE FOUNDERS OF ACADIA . I II. THE BRITISH IN ACADIA . 17 III. THE OATH OF ALLEGIANCE . 28 IV. IN TIMES OF WAR . 47 V. CORNWALLIS AND THE ACADIANS 59 VI. THE 'ANCIENT BOUNDARIES' 71 VII. A LULL IN THE CONFLICT . 83 VIII. THE LAWRENCE REGIME 88 IX. THE EXPULSION . 114 X. THE EXILES . 138 BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTE . 162 INDEX 173 ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE PARISH CHURCH AT GRAND PRE, 1758 . -

British Imperial Strategy in the North Atlantic in the War of Spanish Succession

J.D. ALSOP The Age of the Projectors: British Imperial Strategy in the North Atlantic in the War of Spanish Succession AMBITIOUS PROPOSALS FOR commercial expansion and military conquest in the Atlantic theatres were often promoted during the War of Spanish Succession (1702-1713). One of the striking features of Queen Anne's War, however, was the British government's lack of enthusiasm for such projects. Historians have tended to view the war in the context of long-term imperial issues and with a knowledge of a developing British Empire; from this perspective they have seen the inconsistencies of imperial strategy in this period as a lost opportunity in the construction of the British Empire.1 Although the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713 secured several gains for Britain, including a favourable resolution of the disputed claims to Newfoundland, Hudson's Bay and Nova Scotia, the colonial objectives of the war were limited. British wartime strategy was directed primarily to the successful completion of the European struggle; overseas goals were restricted largely to the maintenance of a favourable status quo. British policy-makers were clearly not as committed to imperial expansion as it seems in retrospect they might have been. In large part this was because they lacked the resources and the mentality for such initiatives and were under no significant pressure to undertake aggressive expansionist projects. The central administration formulated trans-Atlantic wartime strategy without access to independent sources of reliable and relevant information. Instead the government depended heavily upon mercantile interest groups and individual promoters to propose and implement overseas imperial projects. -

The Epidemic Or Pandemic of Influenza in 1708-1709 Agrees with the First of the Two Items Already Quoted Fi-Om the Executiue Jour- Nals 4Thcmd

The epidemic or pandemic of influenza in SAUL JARCHO * KATHERINE M. RICHARDS There is no remembrance of former things; neither shaü there be any remembrance of things that are to come with those that shaü come after. ECCL. 1.1 1. In the years 1708 and 1709 an outbreak of respiratory disease afflicted almost all of western Europe. It was descnbed by the famous Giovanni Maria Lancisi (1654-1720), who designated it as epidemia rheumatica, (1) a term which reflects the Hippocratic and Galenic concept that the disease is a rheuma or flow of noxious humors which descend from the brain (2). The outbreak was discussed repeatedly by Lancisi's contemporaries (3) and by writers of subsequent times. Recently the subject was studied anew by the senior author of (4) the present essay, who agreed with several previous com- (1) LANCISI, Johannes Maria (17 11). Dissertatio de nativis, degue adventitiis Romani coeli gualita- tibus, cui accedit historia epidemiae rheumatuae, yuae per hyemem anni MDCCIX vagata est. Rome, Gonzaga. Through the courtesy of Sig. Angelo Palma, the senior author of the present essay was permitted to examine Lancisi's heavily emended manuscnpt, which is MS no. 157 in the Biblioteca Lancisiana in Rome. The treatise on influenza occupies pp. 209-278 of the bound manuscnpt. In the title the word RHEUMATICA was at first spe- lled without the H; the missing letter was intercalated with a caret. (2) A similar notion is expressed by the term cata~rh,which appears again and again in des- cnptions of the disease. (3) To the eighteenth-century Italian sources commonly cited we wish to add two unpublis- hed manuscnpt discussions tentatively attnbuted to Ippolito Francesco Albertini (1662- 1738). -

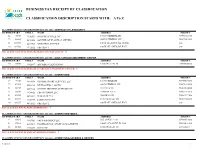

BUSINESS TAX RECEIPT by CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION DESCRIPTION STARTS WITH: a to Z

BUSINESS TAX RECEIPT BY CLASSIFICATION CLASSIFICATION DESCRIPTION STARTS WITH: A To Z CLASSIFICATION # AND DESCRIPTION: 001-000 - ABSTRACT TITLE/SECURITY LICENSE YEAR/# CTRL # NAME ADDRESS PHONE # 22 76015 4450503 INTEGRITY TITLE INC 1356 N FEDERAL HY 954-691-1950 22 46865 4426546 SOUTHEAST FLORIDA LAWYERS 4209 N FEDERAL HY 954-784-2961 21 104371 4473761 MYSTERY LICENSES 100 W ATLANTIC BL CHMB 0-0- 20 102766 4472622 FBS TEST 1 100 W ATLANTIC BL HALL 0-0- TOTAL # OF LICENCES FOR ABSTRACT TITLE/SECURITY: 4 CLASSIFICATION # AND DESCRIPTION: 007-001 - ADULT ARCADE AMUSEMENT CENTER LICENSE YEAR/# CTRL # NAME ADDRESS PHONE # 20 90646 4462847 ARCADE PUBLICATIONS 1280 SW 26 AV 10 754-366-6026 TOTAL # OF LICENCES FOR ADULT ARCADE AMUSEMENT CENTER: 1 CLASSIFICATION # AND DESCRIPTION: 003-001 - ADVERTISING LICENSE YEAR/# CTRL # NAME ADDRESS PHONE # 19 93115 4464836 GLOBAL CHART SERVICES, LLC 1563 N DIXIE HY 888-666-9081 22 87424 4460233 BILLBOARDS 2 GO INC 848 N FEDERAL HY 954-763-9800 21 50117 4418624 HI TECH PRINTING SYSTEMS INC 3411 NE 6 TE 954-480-6088 21 58640 4436002 CBS OUTDOOR LLC 2640 NW 17 LA 954-971-2995 21 86501 4459482 XARALAX LLC 760 SW 12 AV 954-670-7104 22 39574 4420739 JAMES ROSS INC 1180 SW 36 AV 101 954-974-6640 20 102767 4472623 FBS TEST 2 100 W ATLANTIC BL HALL 0-0- TOTAL # OF LICENCES FOR ADVERTISING: 7 CLASSIFICATION # AND DESCRIPTION: 003-002 - ADVERTISING-MEDIA LICENSE YEAR/# CTRL # NAME ADDRESS PHONE # 21 93525 4465183 SACH AD GROUP LLC 565 OAKS LA 101 954-647-3063 21 57882 4435411 PROFESSIONAL SHOW MANAGEMENT 1000 E ATLANTIC -

George, Charlotte, Prince of Cambridge (2013–)

The Kings and Queens of Canada: The Crown in The Canadian Royal Family History HENRY VII (1457–1509). Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) crossed the Atlantic Ocean and explored the Charles d’Orléans, Comte d’Angoulême coast of Newfoundland in 1497. (1459–1496). Marguerite de Navarre (1492–1549). HENRY VIII (1491–1547). Married Henri II, King of Navarre. Wrote FRANÇOIS I (1494–1547). Margaret Tudor Commissioned John Rut to a collection of short stories, including Patron and sponsor of Verrazzano’s voyage (1489–1541). command a Northwest passage one based on the life of Marguerite to Newfoundland in 1524. Sent Cartier Married James IV, expedition in 1527. Rut explored de La Rocque de Robertval, who was to explore the St. Lawrence River in 1534 King of Scots the coast of Labrador in 1527. abandoned on an island off the and sent Roberval to settle Canada in 1541. (1503). coast of Québec. HENRI II (1519–1559). EDWARD VI (1537–1553). MARY I (1516–1558). ELIZABETH I, “The Virgin Jeanne II, André de Thevet, the Married Philip II of Spain, Queen” (1533–1603). James V, reine de Navarre first historian to describe ruler of the Spanish Empire Financed the first voyage of King of Scots (1528–1572). America, was appointed in North and South America. Sir Martin Frobisher in 1576. (1512–1542). Married Antoine royal cosmographer during Mary became the first female In 1578, Sir Humphrey Gilbert de Bourbon. Henri II reign and served four monarch of Canada to obtained letters-patent from consecutive French kings. reign in her own right Queen Elizabeth, empowering (Queen Regnant). -

Erasing Boundaries and Redrawing Lines: the Transition from Port Royal to Annapolis Royal, 1700-1713

Erasing Boundaries and Redrawing Lines: The Transition from Port Royal to Annapolis Royal, 1700-1713 by Carli LaPierre Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia December 2019 © Copyright by Carli LaPierre, 2019 To all the helping hands along the way. ii Table of Contents List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... iv Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vii Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. viii Chapter One: Introduction .................................................................................................... 1 Chapter Two: Defining Lines: Port Royal in the Early Eighteenth Century ................. 12 2.1: The Acadians at Port Royal ...................................................................................... 12 2.2: The French State in Acadia ...................................................................................... 18 2.3: Jean De Labat’s Port Royal ...................................................................................... 20 2.4: Conclusion .................................................................................................................. 43 Chapter Three: Erasing Boundaries: The British Conquest of -

Analyzing Epidemics in New France: the Measles Epidemic of 1714-15

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-11-2011 12:00 AM Analyzing Epidemics in New France: The Measles Epidemic of 1714-15 Ryan M. Mazan The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Alain Gagnon The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Sociology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Ryan M. Mazan 2011 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Recommended Citation Mazan, Ryan M., "Analyzing Epidemics in New France: The Measles Epidemic of 1714-15" (2011). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 141. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/141 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANALYZING EPIDEMICS IN NEW FRANCE: THE MEASLES EPIDEMIC OF 1714-15 (Thesis Format: Integrated Article) By Ryan Michael Mazan Graduate Program in Sociology A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada April 2011 © Ryan Michael Mazan 2011 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO SCHOOL OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ ______________________________ -

31295020692165.Pdf (11.25Mb)

Assimilation versus Autonomy: Acadian and British Contentions, 1713-1755 by Laurie Wood A SENIOR THESIS for the UNIVERSITY HONORS COLLEGE Submitted to the University Honors College at Texas Tech University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree designation of HIGHEST HONORS DECEMBER 2006 Approved by: DR. STEFANO D'AMICO History Department /1-t3-tYo D~. CHRISTINA,ASHsY -MARTIN , I<- Date Honors College DR. GAR~ . BELL ~ Dean, U versity Honors College The author approves the photocopying of this document for educational purposes. he 'Z ^^ TABLE OF CONTENTS 7 I. Introduction 2 A. Historiography II. Geographical and Historical Context 4 Figure 1 European Settlement in Nova Scotia, circa 1750 A. Geography B. Colonial History III. Acadian Identity and Culture 10 A. Society B. Acadians in Relation to British C. Acadians in Relation to Mi'kmaq D. Conflict in Acadia IV. Paul Mascarene 20 Figure 2 Portrait of Major General Paul Mascarene A. Early Life and Career B. "Description of Nova Scotia" C. Diplomacy V. Oaths of Allegiance 27 A. Context B. Early Acadian Oaths C. Oath of 1730 D. Acadian Motives E. "Le Grand Derangemenf Figure 3 Map of Acadian Deportation, 1755-1757 VI. Conclusion 41 A. Acadia after the Expulsion B. Long-Term Effects C. Links VII. Bibliography 47 L INTRODUCTION Recent historical scholarship conceives seventeenth and eighteenth century North America as one region within an Atlantic context that recognizes both European imperial nations and the colonies that they oversaw.' Within this vast geography, Acadia"^ exemphfies the interaction of different cultures during an age of transatlantic trade and colonialism. -

Winter in New France

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1994 That Shocking Season: Winter in New France Pamilla Jeanne Gulley College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Gulley, Pamilla Jeanne, "That Shocking Season: Winter in New France" (1994). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625925. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-z7x7-e410 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THAT SHOCKING SEASON: WINTER IN NEW FRANCE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Pamilla J. Gulley 1994 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Approved, July 1994 A mah James Axtell Tom Sheppan L / h444- /rim whittenburg TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS............................... iv ABSTRACT........................................ v INTRODUCTION....................................2 CHAPTER 1. HOW COLD WAS IT?..................... 6 CHAPTER 2. CONQUERING THE COLD................. 2 6 CONCLUSION..................................... 48 BIBLIOGRAPHY...................................51 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The writer wishes to express her apreciation to Profes sor James Axtell for his guidance on this paper. The author is also very grateful to Professors Tom Sheppard and Jim Whittenburg for reading and commenting on this thesis.