The Crying Clarinet: Emotion and Music in Parakalamos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dzovig Markarian

It is curious to notice that most of Mr. Dellalian’s writings for piano use aleatoric notation, next to extended techniques, to present an idea which is intended to be repeated a number of times before transitioning to the next. The 2005 compilation called “Sounds of Devotion,” where the composer’s family generously present articles, photos and other significant testimony on the composer’s creative life, remembers the two major influences in his music to be modernism and the Armenian Genocide. GUEST ARTIST SERIES ABOUT DZOVIG MARKARIAN Dzovig Markarian is a contemporary classical pianist, whose performances have been described in the press as “brilliant” (M. Swed, LA Times), and “deeply moving, technically accomplished, spiritually uplifting” (B. Adams, Dilijan Blog). An active soloist as well as a collaborative artist, Dzovig is a frequent guest with various ensembles and organizations such as the Dilijan Chamber Music Series, Jacaranda Music at the Edge, International Clarinet Conference, Festival of Microtonal Music, CalArts Chamber Orchestra, inauthentica ensemble, ensemble Green, Xtet New Music Group, USC Contemporary Music Ensemble, REDCAT Festivals of Contemporary Music, as well as with members of the LA PHIL, LACO, DZOVIG MARKARIAN Southwest Chamber Music, and others. Most recently, Dzovig has worked with and premiered works by various composers such as Sofia Gubaidulina, Chinary Ung, Iannis Xenakis, James Gardner, Victoria Bond, Tigran Mansurian, Artur Avanesov, Jeffrey Holmes, Alan Shockley, Adrian Pertout, Laura Kramer and Juan Pablo Contreras. PIANO Ms. Markarian is the founding pianist of Trio Terroir, a Los Angeles based contemporary piano trio devoted to new and complex music from around the world. -

TUBERCULOSIS in GREECE an Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country by J

TUBERCULOSIS IN GREECE An Experiment in the Relief and Rehabilitation of a Country By J. B. McDOUGALL, C.B.E., M.D., F.R.C.P. (Ed.), F.R.S.E.; Late Consultant in Tuberculosis, Greece, UNRRA INTRODUCTION In Greece, we follow the traditions of truly great men in all branches of science, and in none more than in the science of medicine. Charles Singer has rightly said - "Without Herophilus, we should have had no Harvey, and the rise of physiology might have been delayed for centuries. Had Galen's works not survived, Vesalius would have never reconstructed anatomy, and surgery too might have stayed behind with her laggard sister, Medicine. The Hippo- cratic collection was the necessary and acknowledged basis for the work of the greatest of modern clinical observers, Sydenham, and the teaching of Hippocrates and his school is still the substantial basis of instruction in the wards of a modern hospital." When we consider the paucity of the raw material with which the Father of Medicine had to work-the absence of the precise scientific method, a population no larger than that of a small town in England, the opposition of religious doctrines and dogma which concerned themselves largely with the healing art, and a natural tendency to speculate on theory rather than to face the practical problems involved-it is indeed remarkable that we have been left a heritage in clinical medicine which has never been excelled. Nearly 2,000 years elapsed before any really vital advances were made on the fundamentals as laid down by the Hippocratic School. -

A Survey of Scale Insects in Soil Samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha)

A peer-reviewed open-access journal ZooKeys 565: 1–28A survey (2016) of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha) 1 doi: 10.3897/zookeys.565.6877 RESEARCH ARTICLE http://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research A survey of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha) Mehmet Bora Kaydan1,2, Zsuzsanna Konczné Benedicty1, Balázs Kiss1, Éva Szita1 1 Plant Protection Institute, Centre for Agricultural Research, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, Herman Ottó u. 15 H-1022 Budapest, Hungary 2 Çukurova Üniversity, Imamoglu Vocational School, Adana, Turkey Corresponding author: Éva Szita ([email protected]) Academic editor: R. Blackman | Received 17 October 2015 | Accepted 31 December 2015 | Published 17 February 2016 http://zoobank.org/50B411DB-C63F-4FA4-8D1F-C756B304FBD7 Citation: Kaydan MB, Konczné Benedicty Z, Kiss B, Szita É (2016) A survey of scale insects in soil samples from Europe (Hemiptera, Coccomorpha). ZooKeys 565: 1–28. doi: 10.3897/zookeys.565.6877 Abstract In the last decades, several expeditions were organized in Europe by the researchers of the Hungarian Natural History Museum to collect snails, aquatic insects and soil animals (mites, springtails, nematodes, and earthworms). In this study, scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccomorpha) specimens extracted from Hun- garian Natural History Museum soil samples (2970 samples in total), all of which were collected using soil and litter sampling devices, and extracted by Berlese funnel, were examined. From these samples, 43 scale insect species (Acanthococcidae 4, Coccidae 2, Micrococcidae 1, Ortheziidae 7, Pseudococcidae 21, Putoidae 1 and Rhizoecidae 7) were found in 16 European countries. In addition, a new species belong- ing to the family Pseudococcidae, Brevennia larvalis Kaydan, sp. -

IRCA FOREIGN LOG 10Th Edition +Hrd Again W/Light Inst Mx at 0456 on 1/4

IRCA FOREIGN LOG 10th Edition +Hrd again w/light Inst mx at 0456 on 1/4. Poorer than before. (PM-OR) DX World Wide – West +NRK 0244 12/29 country music occasionally coming thru clearly in domestic TRANS-ATLANTIC DX ROUNDUP slop (I've logged & QSLed this one with this early Mon morning country-music show before). First time I've had audio from this one all season. [Stewart-MO] 162 FRANCE , Allouis, 0230 3/7. Male DJ hosting a program of mainly EE pop +2/15 0503 Poor to fair signals in NN talk and oldies mx. Only TA on the MW songs. Fair signal, but much weaker than Iceland. (NP-AB) band. (VAL-DX) +0406 4/18, pop song in FF. (NP-AB*) 1467 FRANCE , Romoules TRW, 12/27 2309 Fair signals peaking w/good Choraol 189 ICELAND , Guguskalar Rikisutvarpid, 2/15 0032. Fair signals with Icelandic mx and rel mx. Het on this one was huge! New station and new Country on talk and a mix of mx some in EE. Only LW station to produce audio. MW. (SA-MB) (VAL-DX) 1512 SAUDI ARABIA , Jeddah BSKSA, 12/27 2248 poor signals w/AA mx and talk. +0227 3/7. Very good signal w/EE lang R&B pop/rock songs hosted by man in New station. (SA-MB) what I presumed was Icelandic. Ranks up there as the best signal I've hrd +12/29 seemed to sign on right at 0300 with no announcements, int signal, from them. (NP-AB) anthem, or anything, just Koranic chanting. -

Comprehensive Services for Survivors of Human Trafficking

FINAL REPORT REPORT FINAL JUNE Comprehensive Services for Survivors of Human 2006 Trafficking: Findings from Clients in Three Communities Final Report Laudan Y. Aron The Urban Institute Janine M. Zweig The Urban Institute Lisa C. Newmark Crime Victim Consultant URBAN INSTITUTE Justice Policy Center Draft-5.24.04 URBAN INSTITUTE Justice Policy Centre 2100 M Street NW Washington, DC 20037 www.urban.org © 2006 Urban Institute This study was part of a larger study conducted by Caliber, an ICF International Company and was supported through subcontract #S813. The full project was supported by Grant No. 2002- MU-MU-K004 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Caliber, an ICF International Company, was the lead research organization for the project. The findings presented in this report are part of a larger report incorporating the full findings of the study. The authors would like to thank the staff, interpreters, and, most importantly, the clients of the Comprehensive Services Site grantees who were willing to spend the time to schedule and participate in these interviews. The authors would also like to thank Kevonne Small for her thoughtful review and contribution to the report. Opinions expressed in this document are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the National Institute of Justice, Caliber (an ICF International Company), or the Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. URBAN INSTITUTE The views expressed are those of the authors, and should not be attributed to The Urban Institute, its trustees, or its funders. -

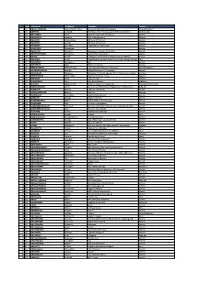

Final List EMD2015 02062015

N° Title LastName FirstName Company Country 1 Dr ABDUL RAHMAN Noorul Shaiful Fitri Universiti Malaysia Terengganu United Kingdom 2 Mr ABSPOEL Lodewijk Nl Ministry For Infrastructure And Environment Netherlands 3 Mr ABU-JABER Nizar German Jordanian University Jordan 4 Ms ADAMIDOU Despina Een -Praxi Network Greece 5 Mr ADAMOU Christoforos Ministry Of Tourism Greece 6 Mr ADAMOU Ioannis Ministry Of Tourism Greece 7 Mr AFENDRAS Evangelos Independent Consultant Greece 8 Mr AFENTAKIS Theodoros Greece 9 Mr AGALIOTIS Dionisios Vocational Institute Of Piraeus Greece 10 Mr AGATHOCLEOUS Panayiotis Cyprus Ports Authority Cyprus 11 Mr AGGOS Petros European Commission'S Representation Athens Greece 12 Dr AGOSTINI Paola Euro-Mediterranean Center On Climate Change (Cmcc) Italy 13 Mr AGRAPIDIS Panagiotis Oss Greece 14 Ms AGRAPIDIS Sofia Rep Ec In Greece Greece 15 Mr AHMAD NAJIB Ahmad Fayas Liverpool John Moores University United Kingdom 16 Dr AIFANDOPOULOU Georgia Hellenic Institute Of Transport Greece 17 Mr AKHALADZE Mamuka Maritime Transport Agency Of The Moesd Of Georgia Georgia 18 Mr AKINGUNOLA Folorunsho Nigeria Merchant Navy Nigeria 19 Mr AKKANEN Mika City Of Turku Finland 20 Ms AL BAYSSARI Paty Blue Fleet Group Lebanon 21 Dr AL KINDI Mohammed Al Safina Marine Consultancy United Arab Emirates 22 Ms ALBUQUERQUE Karen Brazilian Confederation Of Agriculture And Livesto Belgium 23 Mr ALDMOUR Ammar Embassy Of Jordan Jordan 24 Mr ALEKSANDERSEN Øistein Nofir As Norway 25 Ms ALEVRIDOU Alexandra Euroconsultants S.A. Greece 26 Mr ALEXAKIS George Region Of Crete -

INTRODUCTION Zagori: a Historical and Cultural Overview Geography

INTRODUCTION Zagori: a historical and cultural overview Geography and geology Plants and wildlife When to go Getting there Getting around Accommodation Food and drink Language What to take Maps and GPS Weather forecasts Staying safe Emergencies, rescue and health services Using this guide THE ROUTES 1 Central Zagori Walk 1 The round of the stone bridges Walk 2 Kipi to Dilofo and Vitsa Walk 3 Kipi to Kapesovo and Missios Bridge Walk 4 Kipi to Tsepelovo and Kapesovo Walk 5 The Vradeto staircase and Beloi viewpoint Walk 6 Vikaki (Selato) Gorge Walk 7 Mt Mitsikeli Walk 8 Iliochori waterfalls 2 Vikos Gorge and vicinity Walk 9 Vikos Gorge crossing Walk 10 Oxia viewpoint Walk 11 Voidomatis Springs and Theotokos Monastery Walk 12 Voidomatis Gorge crossing Walk 13 Kokkino Lithari viewpoint Walk 14 Papigo villages and Ovires Rogovou natural pools Trek 1 An alternative approach to the Vikos Gorge 3 Mt Timfi Walk 15 Astraka Refuge and Drakolimni Lake Walk 16 Robozi Lake Walk 17 Gamila summit Walk 18 Astraka summit Walk 19 The round of Astraka Walk 20 The Davalista trail (Astraka Refuge to Konitsa) Walk 21 Astraka Refuge to Konitsa or Vrisochori over the Karteros Pass Walk 22 Tsepelovo to Vrisochori traverse Trek 2 The ultimate Zagori trek 4 Konitsa and Mt Smolikas Walk 23 Mt Trapezitsa and Roidovouni Peak Walk 24 Stomiou Monastery Walk 25 Konitsa to Vrisochori traverse Walk 26 Pades to Drakolimni of Smolikas Lake Trek 3 The classic ascent to the Dragonlake of Smolikas 5 Valia Calda National Park and Metsovo Walk 27 Valia Calda National Park Walk 28 Avgo Peak Walk 29 The Flega Lakes Walk 30 Following the footprints of the brown bear in Metsovo Appendix A Route summary table Appendix B Useful contacts and other practical information Appendix C English-Greek glossary and expressions Appendix D Further reading Updates . -

Paths to Innovation in Culture Paths to Innovation in Culture Includes Bibliographical References and Index ISBN 978-954-92828-4-9

Paths to Innovation in Culture Paths to Innovation in Culture Includes bibliographical references and index ISBN 978-954-92828-4-9 Editorial Board Argyro Barata, Greece Miki Braniste, Bucharest Stefka Tsaneva, Goethe-Institut Bulgaria Enzio Wetzel, Goethe-Institut Bulgaria Dr. Petya Koleva, Interkultura Consult Vladiya Mihaylova, Sofia City Art Gallery Malina Edreva, Sofia Municipal Council Svetlana Lomeva, Sofia Development Association Sevdalina Voynova, Sofia Development Association Dr. Nelly Stoeva, Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” Assos. Prof. Georgi Valchev, Deputy Rector of Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridski” Design and typeset Aleksander Rangelov Copyright © 2017 Sofia Development Association, Goethe-Institut Bulgaria and the authors of the individual articles. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction: Paths to Innovation in Culture ....................................................... 8 Digital and Tech Innovation in Arts and Culture Vladiya Mihaylova, Overview ...............................................................................15 Stela Anastasaki Use of Mobile Technologies in Thessaloniki’s Museums. An Online Survey 2017 ..................................................................................... 17 Veselka Nikolova Digital Innovation in Culture ......................................................................... -

PREVIEW the 2013 OFF the COUCH TRAINING PROGRAM BARRIO SITE VISIT | WEEK 1 with Barrio Team from Adelaide Festival of the Arts P

PREVIEW THE 2013 OFF THE COUCH TRAINING PROGRAM BARRIO SITE VISIT | WEEK 1 with Barrio team from Adelaide Festival of the Arts Thursday 14 March at Barrio, 6pm - 8pm www.adelaidefestival.com.au/2013/club/barrio PUBLICITY | WEEK 2 with journalists, bloggers, promoters and venue bookers Thursday 21 March at Carclew, 6-8pm Sose Fuamoli | The AU Review www.theaureview.com/users/sosefina-fuamoli Sose’s career in the arts began in 2006, when she toured and performed with Darwin-based dance company, Sunameke. Relocating to Adelaide in 2009, Sose graduated with a Bachelor of Arts in English and classics from Adelaide University. Sose has been working as a music journalist and editor for a variety of online and press publications for the past four years. She is currently the South Australian Manager and Head News Editor of Sydney- based music and arts publication, The AU Review. Having worked with a variety of Australian and international artists, showcasing Adelaide’s talent has always remained a priority for Sose. Her work has been published Australia-wide and has more recently been featured by CMJ in New York. Luke Penman | play/pause/play www.playpauseplay.com A few years ago Luke came to the realisation that, despite living in Adelaide, he didn't know any bands from Adelaide. He also realised how much he hated working in dead-end office jobs and vowed to break into the music industry. Fast-forward a few years and Luke has dabbled in artist management and promotions while also running an Adelaide music blog and podcast and hosting Local Noise on Radio Adelaide. -

Modern Laments in Northwestern Greece, Their Importance in Social and Musical Life and the “Making” of Oral Tradition

Karadeniz Technical University State Conservatory © 2017 Volume 1 Issue 1 December 2017 Research Article Musicologist 2017. 1 (1): 95-140 DOI: 10.33906/musicologist.373186 ATHENA KATSANEVAKI University of Macedonia, Thessaloniki, Greece [email protected] orcid.org/0000-0003-4938-4634 Modern Laments in Northwestern Greece, Their Importance in Social and Musical Life and the “Making” of Oral Tradition ABSTRACT Having as a starting point a typical phrase -“all our songs once were KEYWORDS laments”- repeated to the researcher during fieldwork, this study aims Lament practices to explore the multiple ways in which lament practices become part of other musical practices in community life or change their Death rituals functionalities and how they contribute to music making. Though the Moiroloi meaning of this typical phrase seems to be inexplicable, nonetheless as Musical speech a general feeling it is shared by most of the people in the field. Starting from the Epirot instrumental ‘moiroloi’, extensive field research Lament-song reveals that many vocal practices considered by former researchers to Symbolic meaning be imitations of instrumental musical practices, are in fact, definite lament vocal practices-cries, embodied and reformed in different ways Collective memory in other musical contexts and serving in this way different social purposes. Furthermore, multiple functionalities of lament practices in social life reveal their transformations into songs and the ways they contribute to music making in oral tradition while at the same time confirming the flexibility of the border between lament and song established by previous researchers. Received: November 17, 2017; Accepted: December 07, 2017 95 The first attempts1 to document Greek folk songs in texts by both Greeks and foreigners included references to, or descriptions of, lament practices. -

The Poetry of Symbolism and the Music of Gabriel Fauré

THE POETRY OF SYMBOLISM AND THE MUSIC OF GABRIEL FAURÉ A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY LYNNELL LEWIS ADVISOR: DR MEI ZHONG BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction ................................................................................... 1 2. Gabriel Fauré .................................................................................. 3 3. Fauré‟s Work and the Influences of Late 19th Century France .... 7 4. Paul Verlaine ................................................................................. 9 5. Fauré, Verlaine and Symbolism ..................................................... 14 6. Description of Songs and Performance issues ............................... 17 . Mandolin .............................................................................. 17 . En Sourdine .......................................................................... 18 . Green .................................................................................... 19 . A Clymène ........................................................................... 21 . C‟est l‟exstase ...................................................................... 23 7. Conclusion ...................................................................................... 25 Appendix of Poetry .............................................................................. 27 Mandoline ...................................................................................... -

Download Bibliography As .Pdf

BIBLIOGRAPHY BY SITE A Aetos http://www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes/pdfs/LB_EPKA.pdf Agia Kyriaki Dakaris, S. (1972), Θεσπρωτία (Athens: Athens Centre of Ekistics). Agioi Apostoloi http://www.yppo.gr/0/anaskafes/pdfs/IB_EPKA.pdf Agios Donatos Forsén, B. (2011), 'Catalogue of Sites in the Central Kokytos Valley', in B. Forsén and E. Tikkala (eds.), Thesprotia expedition II, Environment and settlement patterns (Helsinki), 73-122. http://www.finninstitute.gr/en/thesprotia# 'Thesprotia Expedition 2004-5, Reports' Agios Georgios Dakaris, S. (1971), Cassopaia and the Elean colonies (Athens: Athens Center of Ekistics). Agios Minas Dausse, M.P. (2007), 'Les villes molosses: bilan et hypothèses sur les quatre centres mentionnés par Tite-Live', in D. Berranger-Auserve (ed.), Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine: Mélanges offerts au Professeur Pierre Cabanes (Clermont-Ferrand), 197-233. http://listedmonuments.culture.gr/fek.php?ID_FEKYA=12769 Agora (fortification and graves) Dakaris, S. (1972), Θεσπρωτία (Athens: Athens Centre of Ekistics). Agora PS29, PS30 and PS49 Forsén, B. (2011), 'Catalogue of Sites in the Central Kokytos Valley', in B. Forsén and E. Tikkala (eds.), Thesprotia expedition II, Environment and settlement patterns (Helsinki), 73-122. Almoutses Youni, P., Katsadima, I., and Faklari, I. (2001-4), 'Θέση Αλμούτσες, Κοινότητα Σελλάδων', Archaiologikon Deltion, 56-59 (B), 131-33. Alpochori Dakaris, S. (1971), Cassopaia and the Elean colonies (Athens: Athens Center of Ekistics). Amantia Anamali, S. (1972), 'Amantia', Iliria, II, 67-148. Cabanes, Pierre, et al. (2008), Carte archéologique de l'Albanie (Tirana: Klosi & Benzenberg). Ceka, N. (1990), 'Städtebau in der vorrömischen Periode in Südillyrien', Akten des XIII. Internationalen Kongresses für klassische Archäologie, Berlin, 1988 International Congress of Classical Archaeology (Mainz: Philipp von Zabern), 215-29.