Oklahoma Native Plant Record, Volume 13, Number 1, December

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flora Del Bajío Y De Regiones Adyacentes

FLORA DEL BAJÍO Y DE REGIONES ADYACENTES Fascículo 157 septiembre de 2008 COMPOSITAE* TRIBU HELIANTHEAE I** (géneros Acmella - Jefea) Por Jerzy Rzedowski***,**** y Graciela Calderón de Rzedowski Instituto de Ecología, A.C. Centro Regional del Bajío Pátzcuaro, Michoacán Plantas herbáceas, arbustivas, a veces arborescentes o trepadoras; hojas con más frecuencia opuestas, simples, tri o triplinervadas y serradas en el margen, aun- que con muchas excepciones fuera de este patrón; cabezuelas homógamas o he- terógamas, a veces completamente unisexuales y entonces las plantas monoicas; * La descripción de la familia puede consultarse en el fascículo 32 de esta serie. ** Referencias: Bentham, G. Notes on the classification, history and geographical distribution of the Compositae. J. Linn. Soc. Bot. 13: 253-382. 1873. Blake, S. F. (en colaboración con B. L. Robinson y J. M. Greenman). Asteraceae. In: Standley, P. C., Trees and shrubs of Mexico. Contr. U.S. Nat. Herb. 23: 1401-1641. 1926. Bremer, K. Asteraceae, cladistics & classification. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon. 752 pp. 1994. McVaugh, R. Compositae. Flora Novo-Galiciana. Vol. 12. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Mich. 1157 pp. 1984. Nash, D. L., L. O. Williams et al. Compositae. Flora of Guatemala. Fieldiana, Bot. 24(12): 1-603. 1976. Strother, J. L. Compositae-Heliantheae. Flora of Chiapas. Part V. California Academy of Sciences, San Francisco. 232 pp. 1999. *** Se agradece al Bibl. Armando Butanda su ayuda en la reproducción de las imágenes de láminas de publicaciones antiguas; se dan las gracias asimismo a la Dra. Socorro González Elizondo por haber realizado una búsqueda especial de la población de Coreopsis maysillesii en su localidad tipo. -

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto De Biología, UNAM September 17-23

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto de Biología, UNAM September 17-23 LOCAL ORGANIZERS Hilda Flores-Olvera, Salvador Arias and Helga Ochoterena, IBUNAM ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Walter G. Berendsohn and Sabine von Mering, BGBM, Berlin, Germany Patricia Hernández-Ledesma, INECOL-Unidad Pátzcuaro, México Gilberto Ocampo, Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México Ivonne Sánchez del Pino, CICY, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Thomas Borsch, BGBM, Germany Fernando O. Zuloaga, Instituto de Botánica Darwinion, Argentina Victor Sánchez Cordero, IBUNAM, México Cornelia Klak, Bolus Herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa Hossein Akhani, Department of Plant Sciences, School of Biology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Iran Alexander P. Sukhorukov, Moscow State University, Russia Michael J. Moore, Oberlin College, USA Compilation: Helga Ochoterena / Graphic Design: Julio C. Montero, Diana Martínez GENERAL PROGRAM . 4 MONDAY Monday’s Program . 7 Monday’s Abstracts . 9 TUESDAY Tuesday ‘s Program . 16 Tuesday’s Abstracts . 19 WEDNESDAY Wednesday’s Program . 32 Wednesday’s Abstracs . 35 POSTERS Posters’ Abstracts . 47 WORKSHOPS Workshop 1 . 61 Workshop 2 . 62 PARTICIPANTS . 63 GENERAL INFORMATION . 66 4 Caryophyllales 2018 Caryophyllales General program Monday 17 Tuesday 18 Wednesday 19 Thursday 20 Friday 21 Saturday 22 Sunday 23 Workshop 1 Workshop 2 9:00-10:00 Key note talks Walter G. Michael J. Moore, Berendsohn, Sabine Ya Yang, Diego F. Registration -

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE

Guide to the Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia, Working Draft of 17 March 2004 -- LILIACEAE LILIACEAE de Jussieu 1789 (Lily Family) (also see AGAVACEAE, ALLIACEAE, ALSTROEMERIACEAE, AMARYLLIDACEAE, ASPARAGACEAE, COLCHICACEAE, HEMEROCALLIDACEAE, HOSTACEAE, HYACINTHACEAE, HYPOXIDACEAE, MELANTHIACEAE, NARTHECIACEAE, RUSCACEAE, SMILACACEAE, THEMIDACEAE, TOFIELDIACEAE) As here interpreted narrowly, the Liliaceae constitutes about 11 genera and 550 species, of the Northern Hemisphere. There has been much recent investigation and re-interpretation of evidence regarding the upper-level taxonomy of the Liliales, with strong suggestions that the broad Liliaceae recognized by Cronquist (1981) is artificial and polyphyletic. Cronquist (1993) himself concurs, at least to a degree: "we still await a comprehensive reorganization of the lilies into several families more comparable to other recognized families of angiosperms." Dahlgren & Clifford (1982) and Dahlgren, Clifford, & Yeo (1985) synthesized an early phase in the modern revolution of monocot taxonomy. Since then, additional research, especially molecular (Duvall et al. 1993, Chase et al. 1993, Bogler & Simpson 1995, and many others), has strongly validated the general lines (and many details) of Dahlgren's arrangement. The most recent synthesis (Kubitzki 1998a) is followed as the basis for familial and generic taxonomy of the lilies and their relatives (see summary below). References: Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (1998, 2003); Tamura in Kubitzki (1998a). Our “liliaceous” genera (members of orders placed in the Lilianae) are therefore divided as shown below, largely following Kubitzki (1998a) and some more recent molecular analyses. ALISMATALES TOFIELDIACEAE: Pleea, Tofieldia. LILIALES ALSTROEMERIACEAE: Alstroemeria COLCHICACEAE: Colchicum, Uvularia. LILIACEAE: Clintonia, Erythronium, Lilium, Medeola, Prosartes, Streptopus, Tricyrtis, Tulipa. MELANTHIACEAE: Amianthium, Anticlea, Chamaelirium, Helonias, Melanthium, Schoenocaulon, Stenanthium, Veratrum, Toxicoscordion, Trillium, Xerophyllum, Zigadenus. -

A Checklist of the Vascular Flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center, Tulsa County, Oklahoma

Oklahoma Native Plant Record 29 Volume 13, December 2013 A CHECKLIST OF THE VASCULAR FLORA OF THE MARY K. OXLEY NATURE CENTER, TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA Amy K. Buthod Oklahoma Biological Survey Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory Robert Bebb Herbarium University of Oklahoma Norman, OK 73019-0575 (405) 325-4034 Email: [email protected] Keywords: flora, exotics, inventory ABSTRACT This paper reports the results of an inventory of the vascular flora of the Mary K. Oxley Nature Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. A total of 342 taxa from 75 families and 237 genera were collected from four main vegetation types. The families Asteraceae and Poaceae were the largest, with 49 and 42 taxa, respectively. Fifty-eight exotic taxa were found, representing 17% of the total flora. Twelve taxa tracked by the Oklahoma Natural Heritage Inventory were present. INTRODUCTION clayey sediment (USDA Soil Conservation Service 1977). Climate is Subtropical The objective of this study was to Humid, and summers are humid and warm inventory the vascular plants of the Mary K. with a mean July temperature of 27.5° C Oxley Nature Center (ONC) and to prepare (81.5° F). Winters are mild and short with a a list and voucher specimens for Oxley mean January temperature of 1.5° C personnel to use in education and outreach. (34.7° F) (Trewartha 1968). Mean annual Located within the 1,165.0 ha (2878 ac) precipitation is 106.5 cm (41.929 in), with Mohawk Park in northwestern Tulsa most occurring in the spring and fall County (ONC headquarters located at (Oklahoma Climatological Survey 2013). -

Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of Oklahoma I

Information Series #1, June 1998 Mountains, Streams, and Lakes of OklahomaI Kenneth S. Johnson2 INTRODUCTION valleys, hills, and plains throughout most of the re mainder of Oklahoma (Fig. 1). All the major lakes and Mountains and streams define the landscape of reservoirs of Oklahoma are man-made, and they are Oklahoma (Fig. 1). The mountains consist mainly of important for flood contr()l, water supply, recreation, resistant rock masses that were folded, faulted, and and generation of hydroelectric power. Natural lakes thrust upward in the geologic past (Fig. 2), whereas in Oklahoma are limited to oxbow lakes along major the streams have persisted in eroding less-resistant streams and to playa lakes in the High Plains region rock units and lowering the landscape to form broad of the west. Alphabetical List of20 Lakes with Largest Surface Area (from Oklahoma Water Atlas, Oklahoma Water Resources Board) 1. Broken Bow 11. Lake 0' The Cherokees 2. Canton 12. Oologah 3. Eufaula 13. Robert s. Kerr 4. Fort Gibson 14. Sardis 5. Foss 15. Skiatook 6. Great Salt Plains 16. Tenkiller Ferry ·7. Hudson 17. Texoma 8. Hugo 18. Waurika 9. Kaw 19. Webbers Falls 10. Keystone 20. Wister Modified from Historical Atlas of Oklahoma, by John W. Morris, Charles R. Goins, and Edwin C. 25 McReynolds. Copyright © 1986 by the University I of Oklahoma Press. o 40 80Km Figure 1. Mountains, streams, and principal lakes of Oklahoma. lReprinted from Oklahoma Geology Notes (1993), vol. 53, no. 5, p. 180-188. The Notes article was reprinted and expanded from Oklahoma Almanac, 1993-1994, Oklahoma Department of Lihraries, p. -

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source

Pima County Plant List (2020) Common Name Exotic? Source McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies concolor var. concolor White fir Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abies lasiocarpa var. arizonica Corkbark fir Devender, T. R. (2005) Abronia villosa Hariy sand verbena McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon abutiloides Shrubby Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon berlandieri Berlandier Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon incanum Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Abutilon malacum Yellow Indian mallow Devender, T. R. (2005) Abutilon mollicomum Sonoran Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon palmeri Palmer Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) Abutilon parishii Pima Indian mallow McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon parvulum Dwarf Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium Abutilon pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Abutilon reventum Yellow flower Indian mallow Herbarium; ASU Vascular Plant Herbarium McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia angustissima Whiteball acacia Devender, T. R. (2005); DBGH McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia constricta Whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia greggii Catclaw acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) Acacia millefolia Santa Rita acacia McLaughlin, S. (1992) McLaughlin, S. (1992); Van Acacia neovernicosa Chihuahuan whitethorn acacia Devender, T. R. (2005) McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Acalypha lindheimeri Shrubby copperleaf Herbarium Acalypha neomexicana New Mexico copperleaf McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acalypha ostryaefolia McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acalypha pringlei McLaughlin, S. (1992) Acamptopappus McLaughlin, S. (1992); UA Rayless goldenhead sphaerocephalus Herbarium Acer glabrum Douglas maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer grandidentatum Sugar maple McLaughlin, S. (1992); DBGH Acer negundo Ashleaf maple McLaughlin, S. -

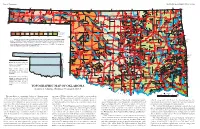

TOPOGRAPHIC MAP of OKLAHOMA Kenneth S

Page 2, Topographic EDUCATIONAL PUBLICATION 9: 2008 Contour lines (in feet) are generalized from U.S. Geological Survey topographic maps (scale, 1:250,000). Principal meridians and base lines (dotted black lines) are references for subdividing land into sections, townships, and ranges. Spot elevations ( feet) are given for select geographic features from detailed topographic maps (scale, 1:24,000). The geographic center of Oklahoma is just north of Oklahoma City. Dimensions of Oklahoma Distances: shown in miles (and kilometers), calculated by Myers and Vosburg (1964). Area: 69,919 square miles (181,090 square kilometers), or 44,748,000 acres (18,109,000 hectares). Geographic Center of Okla- homa: the point, just north of Oklahoma City, where you could “balance” the State, if it were completely flat (see topographic map). TOPOGRAPHIC MAP OF OKLAHOMA Kenneth S. Johnson, Oklahoma Geological Survey This map shows the topographic features of Oklahoma using tain ranges (Wichita, Arbuckle, and Ouachita) occur in southern contour lines, or lines of equal elevation above sea level. The high- Oklahoma, although mountainous and hilly areas exist in other parts est elevation (4,973 ft) in Oklahoma is on Black Mesa, in the north- of the State. The map on page 8 shows the geomorphic provinces The Ouachita (pronounced “Wa-she-tah”) Mountains in south- 2,568 ft, rising about 2,000 ft above the surrounding plains. The west corner of the Panhandle; the lowest elevation (287 ft) is where of Oklahoma and describes many of the geographic features men- eastern Oklahoma and western Arkansas is a curved belt of forested largest mountainous area in the region is the Sans Bois Mountains, Little River flows into Arkansas, near the southeast corner of the tioned below. -

Rare Plants of Louisiana

Rare Plants of Louisiana Agalinis filicaulis - purple false-foxglove Figwort Family (Scrophulariaceae) Rarity Rank: S2/G3G4 Range: AL, FL, LA, MS Recognition: Photo by John Hays • Short annual, 10 to 50 cm tall, with stems finely wiry, spindly • Stems simple to few-branched • Leaves opposite, scale-like, about 1mm long, barely perceptible to the unaided eye • Flowers few in number, mostly born singly or in pairs from the highest node of a branchlet • Pedicels filiform, 5 to 10 mm long, subtending bracts minute • Calyx 2 mm long, lobes short-deltoid, with broad shallow sinuses between lobes • Corolla lavender-pink, without lines or spots within, 10 to 13 mm long, exterior glabrous • Capsule globe-like, nearly half exerted from calyx Flowering Time: September to November Light Requirement: Full sun to partial shade Wetland Indicator Status: FAC – similar likelihood of occurring in both wetlands and non-wetlands Habitat: Wet longleaf pine flatwoods savannahs and hillside seepage bogs. Threats: • Conversion of habitat to pine plantations (bedding, dense tree spacing, etc.) • Residential and commercial development • Fire exclusion, allowing invasion of habitat by woody species • Hydrologic alteration directly (e.g. ditching) and indirectly (fire suppression allowing higher tree density and more large-diameter trees) Beneficial Management Practices: • Thinning (during very dry periods), targeting off-site species such as loblolly and slash pines for removal • Prescribed burning, establishing a regime consisting of mostly growing season (May-June) burns Rare Plants of Louisiana LA River Basins: Pearl, Pontchartrain, Mermentau, Calcasieu, Sabine Side view of flower. Photo by John Hays References: Godfrey, R. K. and J. W. Wooten. -

Riqueza Y Distribución Geográfica De La Tribu Tigridieae

Disponible en www.sciencedirect.com Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 86 (2015) 80-98 www.ib.unam.mx/revista/ Biogeografía Riqueza y distribución geográfica de la tribu Tigridieae (Iridaceae) en Norteamérica Richness and geographic distribution of the tribe Tigridieae (Iridaceae) in North America Guadalupe Munguía-Linoa,c, Georgina Vargas-Amadoa, Luis Miguel Vázquez-Garcíab y Aarón Rodrígueza,* a Instituto de Botánica, Departamento de Botánica y Zoología, Centro Universitario de Ciencias Biológicas y Agropecuarias, Universidad de Guadalajara, Apartado postal 139, 45105 Zapopan, Jalisco, México b Centro Universitario Tenancingo, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, Ex Hacienda de Santa Ana, Km 1.5 carretera Tenancingo-Villa Guerrero, 52400 Tenancingo, Estado de México, México c Doctorado en Ciencias en Biosistemática, Ecología y Manejo de Recursos Naturales y Agrícolas, Universidad de Guadalajara, Apartado postal 139, 45105 Zapopan, Jalisco, México Recibido el 28 de enero de 2014; aceptado el 24 de octubre de 2014 Resumen La tribu Tigridieae (Iridoideae: Iridaceae) es un grupo americano y monofilético. Sus centros de diversificación se localizan en México y la parte andina de Sudamérica. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue analizar la riqueza y distribución de Tigridieae en Norteamérica. Para ello, se utilizó una base de datos con 2,769 registros georreferenciados. Mediante sistemas de información geográfica (SIG) se analizó la riqueza deTigridieae por división política, ecorregión y una cuadrícula de 45×45 km. Tigridieae está representada por 66 especies y 7 subespecies. De estas, 54 especies y 7 subespecies son endémicas. Tigridia es el género más diverso con 43 especies y 6 subespecies. La riqueza de taxa se concentra en México en los estados de Oaxaca, México y Jalisco. -

Illustrated Flora of East Texas Illustrated Flora of East Texas

ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF EAST TEXAS IS PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF: MAJOR BENEFACTORS: DAVID GIBSON AND WILL CRENSHAW DISCOVERY FUND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE FOUNDATION (NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, USDA FOREST SERVICE) TEXAS PARKS AND WILDLIFE DEPARTMENT SCOTT AND STUART GENTLING BENEFACTORS: NEW DOROTHEA L. LEONHARDT FOUNDATION (ANDREA C. HARKINS) TEMPLE-INLAND FOUNDATION SUMMERLEE FOUNDATION AMON G. CARTER FOUNDATION ROBERT J. O’KENNON PEG & BEN KEITH DORA & GORDON SYLVESTER DAVID & SUE NIVENS NATIVE PLANT SOCIETY OF TEXAS DAVID & MARGARET BAMBERGER GORDON MAY & KAREN WILLIAMSON JACOB & TERESE HERSHEY FOUNDATION INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT: AUSTIN COLLEGE BOTANICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE OF TEXAS SID RICHARDSON CAREER DEVELOPMENT FUND OF AUSTIN COLLEGE II OTHER CONTRIBUTORS: ALLDREDGE, LINDA & JACK HOLLEMAN, W.B. PETRUS, ELAINE J. BATTERBAE, SUSAN ROBERTS HOLT, JEAN & DUNCAN PRITCHETT, MARY H. BECK, NELL HUBER, MARY MAUD PRICE, DIANE BECKELMAN, SARA HUDSON, JIM & YONIE PRUESS, WARREN W. BENDER, LYNNE HULTMARK, GORDON & SARAH ROACH, ELIZABETH M. & ALLEN BIBB, NATHAN & BETTIE HUSTON, MELIA ROEBUCK, RICK & VICKI BOSWORTH, TONY JACOBS, BONNIE & LOUIS ROGNLIE, GLORIA & ERIC BOTTONE, LAURA BURKS JAMES, ROI & DEANNA ROUSH, LUCY BROWN, LARRY E. JEFFORDS, RUSSELL M. ROWE, BRIAN BRUSER, III, MR. & MRS. HENRY JOHN, SUE & PHIL ROZELL, JIMMY BURT, HELEN W. JONES, MARY LOU SANDLIN, MIKE CAMPBELL, KATHERINE & CHARLES KAHLE, GAIL SANDLIN, MR. & MRS. WILLIAM CARR, WILLIAM R. KARGES, JOANN SATTERWHITE, BEN CLARY, KAREN KEITH, ELIZABETH & ERIC SCHOENFELD, CARL COCHRAN, JOYCE LANEY, ELEANOR W. SCHULTZE, BETTY DAHLBERG, WALTER G. LAUGHLIN, DR. JAMES E. SCHULZE, PETER & HELEN DALLAS CHAPTER-NPSOT LECHE, BEVERLY SENNHAUSER, KELLY S. DAMEWOOD, LOGAN & ELEANOR LEWIS, PATRICIA SERLING, STEVEN DAMUTH, STEVEN LIGGIO, JOE SHANNON, LEILA HOUSEMAN DAVIS, ELLEN D. -

Vascular Flora of Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area, Anderson County, Texas

2003SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 2(3):347–368 THE VASCULAR FLORA OF GUS ENGELING WILDLIFE MANAGEMENT AREA, ANDERSON COUNTY, TEXAS 1 2,3 2 JASON R. SINGHURST , JAMES C. CATHY , DALE PROCHASKA , 2 4 5 HAYDEN HAUCKE , GLENN C. KROH , AND WALTER C. HOLMES ABSTRACT - Field studies in the Gus Engeling Wildlife Management Area, which consists of approximately 4465.5 ha (11,034.1 acres) of the Post Oak Savannah of Anderson County, have resulted in an annotated checklist of the vascular flora corroborating its remarkable species richness. A total of 930 taxa (excluding family names), belonging to 485 genera and 145 families are re- corded. Asteraceae (124 species), Poaceae (114 species), Fabaceae (67 species), and Cyperaceae (61 species) represented the largest families. Six Texas endemic taxa occur on the site: Brazoria truncata var. pulcherrima (B. pulcherrima), Hymenopappus carrizoanus, Palafoxia reverchonii, Rhododon ciliatus, Trades- cantia humilis, and T. subacaulis. Within Texas, Zigadenus densus is known only from the study area. The area also has a large number of species that are endemic to the West Gulf Coastal Plain and Carrizo Sands phytogeographic distribution patterns. Eleven vegetation alliances occur on the property, with the most notable being sand post oak-bluejack oak, white oak-southern red oak-post oak, and beakrush-pitcher plant alliances. INTRODUCTION The Post Oak Savannah (Gould 1962) comprises about 4,000,000 ha of gently rolling to hilly lands that lie immediately west of the Pineywoods (Timber belt). Some (Allred and Mitchell 1955, Dyksterhuis 1948) consider the vegetation of the area as part of the deciduous forest; i.e., burned out forest that is presently regenerating.