Cumulative Chronological Index of Articles, Muqarnas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

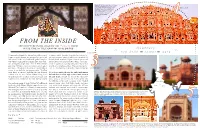

FROM the INSIDE ARCHITECTURE in RELATION to the F E M a L E FORM in the TIME of the INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE Itinerary

Days 5-8 - Exploration of the city of Jaipur with focus on Moghul architecture, such as the HAWA MAHAL located within days in Jaipur the Royal Palace. The original intent of the lattice design was to allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen. 4 FROM THE INSIDE ARCHITECTURE IN RELATION TO THE F e m a l e FORM IN THE TIME OF THE INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE itinerary b e g i n* new delhi jaipur agra If you wander through the hot and crowded streets of windows, called jharokas, that acted as screens be- Jaipur, meander through the grand palace gates, and tween these private quarters and the exterior world. On days in New Delhi find yourself in the very back of the palace complex, the other hand, women held power in these spaces, and you will be confronted by a unique, five story struc- molded these environments to their wills. Their quar- ture of magnificent splendor. It is the Hawa Mahal, ters were organized according to the power they welded and it has 953 lattice covered windows carved out of over the men who housed them. Thus, architecture be- *first and last days are pink stone. Designed in the shape of Lord Krishna’s came the threshold that framed these women’s worlds. reserved3 for travel crown, it was built for one purpose only. To allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals We seek to explore the way the built environment celebrated in the street below without being seen. -

Geometric Patterns and the Interpretation of Meaning: Two Monuments in Iran

BRIDGES Mathematical Connections in Art, Music, and Science Geometric Patterns and the Interpretation of Meaning: Two Monuments in Iran Carol Bier Research Associate, The Textile Museum 2320 S Street, NW Washington, DC 20008 [email protected] Abstract The Alhambra has often served in the West as the paradigm for understanding geometric pattern in Islamic art. Constructed in Spain in the 13th century as a highly defended palace, it is a relatively late manifestation of an Islamic fascination with geometric pattern. Numerous earlier Islamic buildings, from Spain to India, exhibit extensive geometric patterning, which substantiate a mathematical interest in the spatial dimension and its manifold potential for meaning. This paper examines two monuments on the Iranian plateau, dating from the 11 th century of our era, in which more than one hundred exterior surface areas have received patterns executed in cut brick. Considering context, architectural function, and accompanying inscriptions, it is proposed that the geometric patterns carry specific meanings in their group assemblage and combine to form a programmatic cycle of meanings. Perceived as ornamental by Western standards, geometric patterns in Islamic art are often construed as decorative without underlying meanings. The evidence presented in this paper suggests a literal association of geometric pattern with metaphysical concerns. In particular, the argument rests upon an interpretation of the passages excerpted from the Qur' an that inform the patterns of these two buildings, the visual and verbal expression mutually reinforcing one another. Specifically, the range and mUltiplicity of geometric patterns may be seen to represent the Arabic concept of mithal, usually translated as parable or similitude. -

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented. -

Architectural Elements in Islamic Ornamentation: New Vision in Contemporary Islamic Art

Arts and Design Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-6061 (Paper) ISSN 2225-059X (Online) Vol.21, 2014 Architectural Elements in Islamic Ornamentation: New Vision in Contemporary Islamic Art Jeanan Shafiq Interior Design Dpt., Applied Sciences Private University, P.O. Box 166, Amman 11931 Jordan. * E-mail of the corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Throughout history, Islamic Ornamentation was the most characteristic to identify Islamic architecture. It used in mosques and other Islamic buildings. Many studies were about the formation of Islamic art from pre-existing traditional elements and about the nature of the power which wrought all those various elements into a unique synthesis. Nobody will deny the unity of Islamic art, despite the differences of time and place. It’s far too evident, whether one contemplates the mosque of Cordoba, the great schools of Samarkand or Al- Mustansiriya. It’s like the same light shone forth from all these works of art. Islam does not prescribe any particular forms of art. It merely restricts the field of expression. Ideology of Islam depends on the fixed and variable principles. Fixed indicate to the main principles of Islam that could not be changed in place and time including the oneness of God, while the variable depends on human vision in different places through time. It's called the intellectual vision inherited in Islamic art. Islamic Ornamentation today is repeating the same forms, by which, it turns to a traditional heritage art. From this specific point the research problem started. Are we able to find different style of ornament that refers to Islamic Art? Islamic ideology in its original meaning is a faculty of timeless realities. -

The Amalgamation of Indo-Islamic Architecture of the Deccan

Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 255 THE AMALGAMATION OF INDO-ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE DECCAN SHARMILA DURAI Department of Architecture, School of Planning & Architecture, Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture & Fine Arts University, India ABSTRACT A fundamental proportion of this work is to introduce the Islamic Civilization, which was dominant from the seventh century in its influence over political, social, economic and cultural traits in the Indian subcontinent. This paper presents a discussion on the Sultanate period, the Monarchs and Mughal emperors who patronized many arts and skills such as textiles, carpet weaving, tent covering, regal costume design, metallic and decorative work, jewellery, ornamentation, painting, calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts and architecture with their excellence. It lays emphasis on the spread of Islamic Architecture across India, embracing an ever-increasing variety of climates for the better flow of air which is essential for comfort in the various climatic zones. The Indian subcontinent has produced some of the finest expressions of Islamic Art known to the intellectual and artistic vigour. The aim here lies in evaluating the numerous subtleties of forms, spaces, massing and architectural character which were developed during Muslim Civilization (with special reference to Hyderabad). Keywords: climatic zones, architectural character, forms and spaces, cultural traits, calligraphic designs. 1 INTRODUCTION India, a land enriched with its unique cultural traits, traditional values, religious beliefs and heritage has always surprised historians with an amalgamation of varying influences of new civilizations that have adapted foreign cultures. The advent of Islam in India was at the beginning of 11th century [1]. Islam, the third great monotheistic religion, sprung from the Semitic people and flourished in most parts of the world. -

Exploration of Arabesque As an Element of Decoration in Islamic Heritage Buildings: the Case of Indian and Persian Architecture

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Exploration of Arabesque as an Element of Decoration in Islamic Heritage Buildings: The Case of Indian and Persian Architecture Mohammad Arif Kamal Architecture Section Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India Saima Gulzar School of Architecture and Planning University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Sadia Farooq Dept. of Family and Consumer Sciences University of Home Economics, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract - The decoration is a vital element in Islamic art and architecture. The Muslim designers finished various art, artifacts, religious objects, and buildings with many types of ornamentation such as geometry, epigraphy, calligraphy, arabesque, and sometimes animal figures. Among them, the most universal motif in ornamentation which was extensively used is the arabesque. The arabesque is an abstract and rhythmic vegetal ornamentation pattern in Islamic decoration. It is found in a wide variety of media such as book art, stucco, stonework, ceramics, tiles, metalwork, textiles, carpets, etc.. The paper discusses the fact that arabesque is a unique, universal, and vital element of ornamentation within the framework of Islamic Architecture. In this paper, the etymological roots of the term ‘Arabesque’, its evolution and development have been explored. The general characteristics as well as different modes of arabesque are discussed. This paper also analyses the presentation of arabesque with specific reference to Indian and Persian Islamic heritage buildings. Keywords – Arabesque, Islamic Architecture, Decoration, Heritage, India, Iran I. INTRODUCTION The term ‘Arabesque’ is an obsolete European form of rebesk (or rebesco), not an Arabic word dating perhaps from the 15th or 16th century when Renaissance artists used Islamic Designs for book ornament and decorative bookbinding [1]. -

Islamic Ornament

Islamic Ornament ARH 394/MDV 392M/MES 386 fridays 10-1 Stephennie Mulder Soyletoveywebl;zye.eycoxcme/s.we.we Instructor email: [email protected] Classroom Location: ART 3.432 Office: DFA 2.516 Office Hours: Mondays & Wednesdays 9-11 and by appointment Islamic art is famous for its tradition of ornamented surfaces, while Western art has often used ornament primarily to highlight or enhance the impact of an image. This course is a comparative study of the role of ornament, which takes as its founding premise that both Islamic and European art emerged from the same Late Antique visual milieu: in which abstract, geometric, and vegetal ornament played a key, (though often neglected) role. The study of ornament has a long and important history in art and design, but with the advent of modernism, ornament was deemed ethically suspect and inimical to art’s higher purposes. Nevertheless, in the past few decades, under the aegis of postmodern theory, ornament has assumed a renewed significance. We will explore multiple scholars’ perspectives on ornament: its practical function and creation, its ability to transform surfaces and thereby change their reception and meaning, and its role as a semiotic device and broader social function as a marker of class, faith, or exoticism. An important proposal we will explore is the idea that ornament is not mere “decoration,” but rather has a rich functional and symbolic role to play in the human response to and understanding of art. With this role in mind, a key skill students will acquire in this course is the ability to make a visual analysis of a work of art whose primary feature is its ornament. -

Architectural Monuments During Mughals Rule

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 4, Issue - 1, Jan – 2020 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Scientific Journal Impact Factor: 5.245 Received on : 09/01/2020 Accepted on : 20/01/2020 Publication Date: 31/01/2020 Architectural Monuments during Mughals Rule JEOTI PANGGING Assistant Professor, Dept. of History Moran Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Dibrugarh University., Assam, India Email - [email protected] Abstract: There was an incomparable architectural activity in India under the Mughals rule. The traditions in the field of architecture, painting, literature and music created pleasure during this period. The Mughal emperors were keen lovers of nature and art and their personality was, to a certain extent, reflected in the art and culture of their time. Under their patronage, all arts particularly architecture, painting and music made special progress and all kinds of artists used to received encouragement from the state. The Mughal emperors were great builders. So, the Mughal period it regarded as the ‘Golden Age of Architecture’ in the Indian history. The Mughals, their empire, their warriors and their affairs, both of love and war, no longer exist, but their buildings that tell even today to story of their capability and personality, have immortalized them for all times. We can imagine how great builders the Mughals have been by seeing their buildings that are found even to this day. The objectives development under the Mughal Empire. Key Words: Architecture, Mughal empire, patronage, mansion, Fort. 1. INTRODUCTION: With the advent of the Mughals Indo-Muslim architecture reaches a unity and completeness which make the story of the architectural style that developed under their august patronage particularly fascinating and instructive. -

Patterns and Geometry

PATTERNS ROSE CHABUTRA: ICE CHABUTRA: Pentagon and 10-Pointed Star Hexagon and 6-Pointed Star 4 PATTERNS AND GEOMETRY NELSON BYRD WOLTZ LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS Geometric design, based on the spiritual principles of nature, is at the center of Islamic QUESTIONS GROUNDING THE RESEARCH culture. Geometry is regarded as a sacred art form in which craftsmen connected with the The research process began with a series of fundamental questions that eternal; it is a form of prayer or meditation to awaken the soul in the practitioner via the informed the study: act of recollection. Participating “in” geometry is symbolic of creating order in the material 1. How can we respectfully and thoughtfully use this pattern language, which world and a way for the practitioner to bring to consciousness a greater understanding of represents hundreds of years of Islamic culture and design, within the the woven Universe and the Divine. context of a contemporary garden? 2. How can we appropriately apply these patterns in the Aga Khan Garden Islamic art has the power to connect us to nature and the cosmos by revealing patterns with purpose and meaning? inherent in the physical world. While the use of geometry and patterns are intrinsic 3. How can we make these gardens a pleasure for users to experience and elements in Islamic garden design, graphic arts, and architecture, the rules and rationale provide the sensorial delight depicted in extant precedents and historic to their form and application are not cohesively documented. To undertake the design descriptions, such as Mughal miniature paintings? and construction of the Aga Khan Garden, Nelson Byrd Woltz, the landscape architects, 4. -

Curriculum Vitae: Oleg Grabar

CURRICULUM VITAE: OLEG GRABAR Date of Birth: November 3, 1929, Strasbourg, France Secondary Education: Lycées Claude Bernard and Louis-le-Grand, Paris Higher Education: Certificat de licence, Ancient History, University of Paris (1948) B.A. (magna cum laude), Harvard University, Medieval History (1950) Certificats de licence, Medieval History and Modern History, University of Paris (1950) M.A. (1953) and Ph.D. (1955), Princeton University, Oriental Languages and Literatures and History of Art Fellow, 1953-54, American School of Oriental Research, Jerusalem, Jordan PROFESSIONAL HISTORY: Academic 1954-69 University of Michigan: 1954-55 Instructor; 1955-59 Assistant Professor of Near Eastern Art and Near Eastern Studies; 1959-64 Associate Professor; 1964-69 Professor; 1966-67 Acting Chairman, Department of the History of Art. 1969-90 Harvard University: 1969-1980 Professor of Fine Arts; 1973-76 Head Tutor, Department of Fine Arts; 1975-76 Acting Co-Master of North House; 1977-82 Chairman, Department of Fine Arts; 1980-90 Aga Khan Professor of Islamic Art and Architecture; Professor Emeritus since 1990. 1990- Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton: Professor, School of Historical Studies. (1990-1998); Professor Emeritus (1998-). Other 1957-70 Near Eastern Editor, Ars Orientalis 1958-69 Honorary Curator of Near Eastern Art, Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institute 1960-61 Director, American School of Oriental Research, Jerusalem, Jordan 1964-69 Secretary, American Research Institute in Turkey 2 1964-72 Director, Excavations at Qasr al-Hayr -

Chishti Sufis of Delhi in the LINEAGE of HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN

Chishti Sufis of Delhi IN THE LINEAGE OF HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN Compiled by Basira Beardsworth, with permission from: Pir Zia Inayat Khan A Pearl in Wine, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani Sadia Dehlvi Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi All the praise of your advancement in this line is due to our masters in the chain who are sending the vibrations of their joy, love, and peace. - Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, in a letter to Murshida Rabia Martin There is a Sufi tradition of visiting the tombs of saints called ziyarah (Arabic, “visit”) or haazri (Urdu, “attendance”) to give thanks and respect, to offer prayers and seek guidance, to open oneself to the blessing stream and seek deeper connection with the great Soul. In the Chishti lineage through Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, there are nine Pirs who are buried in Delhi, and many more whose lives were entwined with Delhi. I have compiled short biographies on these Pirs, and a few others, so that we may have a glimpse into their lives, as a doorway into “meeting” them in the eternal realm of the heart, insha’allah. With permission from the authors, to whom I am deeply grateful to for their work on this subject, I compiled this information primarily from three books: Pir Zia Inayat Khan, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani, published in A Pearl in Wine Sadia Dehlvi, Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi For those interested in further study, I highly recommend their books – I have taken only small excerpts from their material for use in this document. -

Travels in Andalucia

Collecting Islam: Travels In Andalucia This talk looks at the unique Islamic style of architecture developed by the Moorish rulers of Spain during their rule of the Iberian Peninsula from the 8th to 15th centuries. 1. The Court of the Lions, Alhambra; Charles Clifford (1821 – 1863); Albumen print photograph; ca. 1855 Museum number: 47:790 Charles Clifford was one of the finest photographers of 19th century Spain, and he spent most of his career there. Having settled in Madrid in the 1850s, he became court photographer for Queen Isabella II, and accompanied her on a number of royal tours within Spain. Clifford was very effective at capturing architectural subjects through his technical mastery of the large- format camera. 2. Plans, Elevations, Sections and Details from the Alhambra; Owen Jones and Jules Goury; volume; 1845 Museum number: NAL; 110.P.36 This volume was part one in a series of two, and constituted the main output of Jones and Goury’s observational work in Andalucia. The studies contained within this volume include detailed drawings of ornament, translations of all Arabic inscriptions and an in-depth historical account of the Moorish kings of Granada. To ensure perfect accuracy in the ornament details, plaster impressions were taken of every element of ornament of the Alhambra. Some of these casts were bought by the South Kensington Museum (precursor to the V&A) for students of Oriental art. Jones worked hard to establish a good standard of chromolithographic printing to do justice to the striking Islamic decorative schemes, and in fact as a result was a major force in pushing forward colour printing in England at the time.