Mosque and Mausoleum: Understanding Islam in India

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner

Islamic Geometric Patterns Jay Bonner Islamic Geometric Patterns Their Historical Development and Traditional Methods of Construction with a chapter on the use of computer algorithms to generate Islamic geometric patterns by Craig Kaplan Jay Bonner Bonner Design Consultancy Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA With contributions by Craig Kaplan University of Waterloo Waterloo, Ontario, Canada ISBN 978-1-4419-0216-0 ISBN 978-1-4419-0217-7 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-4419-0217-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017936979 # Jay Bonner 2017 Chapter 4 is published with kind permission of # Craig Kaplan 2017. All Rights Reserved. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are reserved by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery Or Mashrabiya

THE TRADITIONAL ARTS AND CRAFTS OF TURNERY OR MASHRABIYA BY JEHAN MOHAMED A Capstone submitted to the Graduate School-Camden Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Art Graduate Program in Liberal Studies Written under the direction of Dr. Martin Rosenberg And Approved by ______________________________ Dr. Martin Rosenberg Camden, New Jersey May 2015 CAPSTONE ABSTRACT The Traditional Arts and Crafts of Turnery or Mashrabiya By JEHAN MOHAMED Capstone Director: Dr. Martin Rosenberg For centuries, the mashrabiya as a traditional architectural element has been recognized and used by a broad spectrum of Muslim and non-Muslim nations. In addition to its aesthetic appeal and social component, the element was used to control natural ventilation and light. This paper will analyze the phenomenon of its use socially, historically, artistically and environmentally. The paper will investigate in depth the typology of the screen; how the different techniques, forms and designs affect the function of channeling direct sunlight, generating air flow, increasing humidity, and therefore, regulating or conditioning the internal climate of a space. Also, in relation to cultural values and social norms, one can ask how the craft functioned, and how certain characteristics of the mashrabiya were developed to meet various needs. Finally, the study of its construction will be considered in relation to artistic representation, abstract geometry, as well as other elements of its production. ii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………….……….…..ii List of Illustrations………………………………………………………………………..iv Introduction……………………………………………….…………………………….…1 Chapter One: Background 1.1. Etymology………………….……………………………………….……………..3 1.2. Description……………………………………………………………………...…6 1.3. -

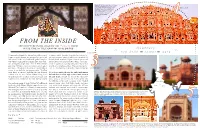

FROM the INSIDE ARCHITECTURE in RELATION to the F E M a L E FORM in the TIME of the INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE Itinerary

Days 5-8 - Exploration of the city of Jaipur with focus on Moghul architecture, such as the HAWA MAHAL located within days in Jaipur the Royal Palace. The original intent of the lattice design was to allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals celebrated in the street below without being seen. 4 FROM THE INSIDE ARCHITECTURE IN RELATION TO THE F e m a l e FORM IN THE TIME OF THE INDIAN MUGHAL EMPIRE itinerary b e g i n* new delhi jaipur agra If you wander through the hot and crowded streets of windows, called jharokas, that acted as screens be- Jaipur, meander through the grand palace gates, and tween these private quarters and the exterior world. On days in New Delhi find yourself in the very back of the palace complex, the other hand, women held power in these spaces, and you will be confronted by a unique, five story struc- molded these environments to their wills. Their quar- ture of magnificent splendor. It is the Hawa Mahal, ters were organized according to the power they welded and it has 953 lattice covered windows carved out of over the men who housed them. Thus, architecture be- *first and last days are pink stone. Designed in the shape of Lord Krishna’s came the threshold that framed these women’s worlds. reserved3 for travel crown, it was built for one purpose only. To allow royal ladies to observe everyday life and festivals We seek to explore the way the built environment celebrated in the street below without being seen. -

Evolution of Islamic Geometric Patterns

Frontiers of Architectural Research (2013) 2, 243–251 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com www.elsevier.com/locate/foar RESEARCH ARTICLE Evolution of Islamic geometric patterns Yahya Abdullahin, Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi1 Faculty of Built Environment, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Johor 81310, Malaysia Received 18 December 2012; received in revised form 27 March 2013; accepted 28 March 2013 KEYWORDS Abstract Islamic geometrical This research demonstrates the suitability of applying Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) to patterns; architectural elements in terms of time scale accuracy and style matching. To this end, a Islamic art; detailed survey is conducted on the decorative patterns of 100 surviving buildings in the Muslim Islamic architecture; architectural world. The patterns are analyzed and chronologically organized to determine the History of Islamic earliest surviving examples of these adorable ornaments. The origins and radical artistic architecture; movements throughout the history of IGPs are identified. With consideration for regional History of architecture impact, this study depicts the evolution of IGPs, from the early stages to the late 18th century. & 2013. Higher Education Press Limited Company. Production and hosting by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 1. Introduction three questions that guide this work are as follows. (1) When were IGPs introduced to Islamic architecture? (2) When was For centuries, Islamic geometrical patterns (IGPs) have been each type of IGP introduced to Muslim architects and artisans? used as decorative elements on walls, ceilings, doors, (3) Where were the patterns developed and by whom? A domes, and minarets. However, the absence of guidelines sketch that demonstrates the evolution of IGPs throughout and codes on the application of these ornaments often leads the history of Islamic architecture is also presented. -

The Amalgamation of Indo-Islamic Architecture of the Deccan

Islamic Heritage Architecture and Art II 255 THE AMALGAMATION OF INDO-ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE OF THE DECCAN SHARMILA DURAI Department of Architecture, School of Planning & Architecture, Jawaharlal Nehru Architecture & Fine Arts University, India ABSTRACT A fundamental proportion of this work is to introduce the Islamic Civilization, which was dominant from the seventh century in its influence over political, social, economic and cultural traits in the Indian subcontinent. This paper presents a discussion on the Sultanate period, the Monarchs and Mughal emperors who patronized many arts and skills such as textiles, carpet weaving, tent covering, regal costume design, metallic and decorative work, jewellery, ornamentation, painting, calligraphy, illustrated manuscripts and architecture with their excellence. It lays emphasis on the spread of Islamic Architecture across India, embracing an ever-increasing variety of climates for the better flow of air which is essential for comfort in the various climatic zones. The Indian subcontinent has produced some of the finest expressions of Islamic Art known to the intellectual and artistic vigour. The aim here lies in evaluating the numerous subtleties of forms, spaces, massing and architectural character which were developed during Muslim Civilization (with special reference to Hyderabad). Keywords: climatic zones, architectural character, forms and spaces, cultural traits, calligraphic designs. 1 INTRODUCTION India, a land enriched with its unique cultural traits, traditional values, religious beliefs and heritage has always surprised historians with an amalgamation of varying influences of new civilizations that have adapted foreign cultures. The advent of Islam in India was at the beginning of 11th century [1]. Islam, the third great monotheistic religion, sprung from the Semitic people and flourished in most parts of the world. -

When Senegalese Tidjanis Meet in Fez: the Political and Economic Dimensions of a Transnational Sufi Pilgrimage

Johara Berriane When Senegalese Tidjanis Meet in Fez: The Political and Economic Dimensions of a Transnational Sufi Pilgrimage Summary The tomb of Ahmad Al-Tidjani in Fez has progressively become an important pilgrimage centre for the Tidjani Sufi order. Ever since the Tidjani teachings started spreading through- out the sub-Saharan region, this historical town has mainly been attracting Tidjani disciples from Western Africa. Most of them come from Senegal were the pilgrimage to Fez (known as ziyara) has started to become popular during the colonial period and has gradually gained importance with the development of new modes of transportation. This article analyses the transformation of the ziyara concentrating on two main aspects: its present concerns with economic and political issues as well as the impact that the transnationalisation of the Tid- jani Senegalese community has on the Tidjani pilgrims to Morocco. Keywords: Sufi shrine; political and economic aspects; tourism; diaspora Dieser Beitrag befasst sich mit der Entwicklung der senegalesischen Tidjaniyya Pilgerreise nach Fès. Schon seit der Verbreitung der Tidjani Lehren im subsaharischen Raum, ist der Schrein vom Begründer dieses Sufi Ordens Ahmad al-Tidjani zu einem bedeutsamen Pilger- ort für westafrikanische und insbesondere senegalesische Tidjaniyya Anhänger geworden. Während der Kolonialzeit und durch die Entwicklung der neuen Transportmöglichkeiten, hat dieser Ort weiterhin an Bedeutung gewonnen. Heute beeinflussen zudem die politi- schen und ökonomischen Interessen Marokkos -

Exploration of Arabesque As an Element of Decoration in Islamic Heritage Buildings: the Case of Indian and Persian Architecture

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology ISSN No : 1006-7930 Exploration of Arabesque as an Element of Decoration in Islamic Heritage Buildings: The Case of Indian and Persian Architecture Mohammad Arif Kamal Architecture Section Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, India Saima Gulzar School of Architecture and Planning University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Sadia Farooq Dept. of Family and Consumer Sciences University of Home Economics, Lahore, Pakistan Abstract - The decoration is a vital element in Islamic art and architecture. The Muslim designers finished various art, artifacts, religious objects, and buildings with many types of ornamentation such as geometry, epigraphy, calligraphy, arabesque, and sometimes animal figures. Among them, the most universal motif in ornamentation which was extensively used is the arabesque. The arabesque is an abstract and rhythmic vegetal ornamentation pattern in Islamic decoration. It is found in a wide variety of media such as book art, stucco, stonework, ceramics, tiles, metalwork, textiles, carpets, etc.. The paper discusses the fact that arabesque is a unique, universal, and vital element of ornamentation within the framework of Islamic Architecture. In this paper, the etymological roots of the term ‘Arabesque’, its evolution and development have been explored. The general characteristics as well as different modes of arabesque are discussed. This paper also analyses the presentation of arabesque with specific reference to Indian and Persian Islamic heritage buildings. Keywords – Arabesque, Islamic Architecture, Decoration, Heritage, India, Iran I. INTRODUCTION The term ‘Arabesque’ is an obsolete European form of rebesk (or rebesco), not an Arabic word dating perhaps from the 15th or 16th century when Renaissance artists used Islamic Designs for book ornament and decorative bookbinding [1]. -

Architectural Monuments During Mughals Rule

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCH CULTURE SOCIETY ISSN: 2456-6683 Volume - 4, Issue - 1, Jan – 2020 Monthly, Peer-Reviewed, Refereed, Indexed Journal Scientific Journal Impact Factor: 5.245 Received on : 09/01/2020 Accepted on : 20/01/2020 Publication Date: 31/01/2020 Architectural Monuments during Mughals Rule JEOTI PANGGING Assistant Professor, Dept. of History Moran Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Dibrugarh University., Assam, India Email - [email protected] Abstract: There was an incomparable architectural activity in India under the Mughals rule. The traditions in the field of architecture, painting, literature and music created pleasure during this period. The Mughal emperors were keen lovers of nature and art and their personality was, to a certain extent, reflected in the art and culture of their time. Under their patronage, all arts particularly architecture, painting and music made special progress and all kinds of artists used to received encouragement from the state. The Mughal emperors were great builders. So, the Mughal period it regarded as the ‘Golden Age of Architecture’ in the Indian history. The Mughals, their empire, their warriors and their affairs, both of love and war, no longer exist, but their buildings that tell even today to story of their capability and personality, have immortalized them for all times. We can imagine how great builders the Mughals have been by seeing their buildings that are found even to this day. The objectives development under the Mughal Empire. Key Words: Architecture, Mughal empire, patronage, mansion, Fort. 1. INTRODUCTION: With the advent of the Mughals Indo-Muslim architecture reaches a unity and completeness which make the story of the architectural style that developed under their august patronage particularly fascinating and instructive. -

Patterns and Geometry

PATTERNS ROSE CHABUTRA: ICE CHABUTRA: Pentagon and 10-Pointed Star Hexagon and 6-Pointed Star 4 PATTERNS AND GEOMETRY NELSON BYRD WOLTZ LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS Geometric design, based on the spiritual principles of nature, is at the center of Islamic QUESTIONS GROUNDING THE RESEARCH culture. Geometry is regarded as a sacred art form in which craftsmen connected with the The research process began with a series of fundamental questions that eternal; it is a form of prayer or meditation to awaken the soul in the practitioner via the informed the study: act of recollection. Participating “in” geometry is symbolic of creating order in the material 1. How can we respectfully and thoughtfully use this pattern language, which world and a way for the practitioner to bring to consciousness a greater understanding of represents hundreds of years of Islamic culture and design, within the the woven Universe and the Divine. context of a contemporary garden? 2. How can we appropriately apply these patterns in the Aga Khan Garden Islamic art has the power to connect us to nature and the cosmos by revealing patterns with purpose and meaning? inherent in the physical world. While the use of geometry and patterns are intrinsic 3. How can we make these gardens a pleasure for users to experience and elements in Islamic garden design, graphic arts, and architecture, the rules and rationale provide the sensorial delight depicted in extant precedents and historic to their form and application are not cohesively documented. To undertake the design descriptions, such as Mughal miniature paintings? and construction of the Aga Khan Garden, Nelson Byrd Woltz, the landscape architects, 4. -

Chishti Sufis of Delhi in the LINEAGE of HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN

Chishti Sufis of Delhi IN THE LINEAGE OF HAZRAT PIR-O-MURSHID INAYAT KHAN Compiled by Basira Beardsworth, with permission from: Pir Zia Inayat Khan A Pearl in Wine, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani Sadia Dehlvi Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi All the praise of your advancement in this line is due to our masters in the chain who are sending the vibrations of their joy, love, and peace. - Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, in a letter to Murshida Rabia Martin There is a Sufi tradition of visiting the tombs of saints called ziyarah (Arabic, “visit”) or haazri (Urdu, “attendance”) to give thanks and respect, to offer prayers and seek guidance, to open oneself to the blessing stream and seek deeper connection with the great Soul. In the Chishti lineage through Hazrat Pir-o-Murshid Inayat Khan, there are nine Pirs who are buried in Delhi, and many more whose lives were entwined with Delhi. I have compiled short biographies on these Pirs, and a few others, so that we may have a glimpse into their lives, as a doorway into “meeting” them in the eternal realm of the heart, insha’allah. With permission from the authors, to whom I am deeply grateful to for their work on this subject, I compiled this information primarily from three books: Pir Zia Inayat Khan, The “Silsila-i Sufian”: From Khwaja Mu’in al-Din Chishti to Sayyid Abu Hashim Madani, published in A Pearl in Wine Sadia Dehlvi, Sufism, The Heart of Islam, and The Sufi Courtyard, Dargahs of Delhi For those interested in further study, I highly recommend their books – I have taken only small excerpts from their material for use in this document. -

TOMBS and FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES and PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN and AFGHANISTAN Wvo't)&^F4

TOMBS AND FOOTPRINTS: ISLAMIC SHRINES AND PILGRIMAGES IN^IRAN AND AFGHANISTAN WvO'T)&^f4 Hugh Beattie Thesis presented for the degree of M. Phil at the University of London School of Oriental and African Studies 1983 ProQuest Number: 10672952 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672952 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 abstract:- The thesis examines the characteristic features of Islamic shrines and pilgrimages in Iran and Afghan istan, in doing so illustrating one aspect of the immense diversity of belief and practice to be found in the Islamic world. The origins of the shrine cults are outlined, the similarities between traditional Muslim and Christian attitudes to shrines are emphasized and the functions of the shrine and the mosque are contrasted. Iranian and Afghan shrines are classified, firstly in terms of the objects which form their principal attrac tions and the saints associated with them, and secondly in terms of the distances over which they attract pilgrims. The administration and endowments of shrines are described and the relationship between shrines and secular authorities analysed. -

Historical Tradition and Modern Transformations of the Algerian and Persian Housing Environment

HOUSING ENVIRONMENT 31/2020 ARCHITEKTURA XXI WIEKU / THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE 21st CENTURY e-ISSN 2543-8700 DOI: 10.4467/25438700SM.20.011.12692 YULIA IVASHKO*, ANDRII DMYTRENKO**, PENG CHANG*** Historical tradition and modern transformations of the algerian and persian housing environment Abstract Historically, the urban situation in the cities and towns of Persia and Algeria was highly specific. The hot dry climate contri- buted to a street network, which was protected from the sun as much as possible. Climate conditions determined the appe- arance of houses with flat roofs, small windows and white walls. The entire urban planning system had the main centre—the city (town) mosque. There were smaller mosques in the structure of residential areas, densely surrounded by houses. Just as under the influence of climate a certain type of residential building took shape, these same factors formed a characteristic type of mosque in the housing environment. Globalist trends have affected even such a conservative sphere as Islamic religious architecture, as it gradually toned down striking regional features, which is explained by the typicality of modern building materials and structures and the interna- tional activity of various architectural and construction firms in different corners of the world. Over the centuries, two oppo- sing images of the mosque have emerged—the pointedly magnificent Persian and the fortress-type of Maghreb (typical for Algeria) types. This paper reviews how specific climatic conditions and historical processes influenced the use of building materials, structures and decoration in the mosques of Persia’s and Algeria’s different regions. Today we observe an erosion of regional features in the form and layout of modern mosques, which are analysed on the basis of the examples given.