Carso, Review of Follies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: the Musical Katherine B

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2016 "Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The Musical Katherine B. Marcus Reker Scripps College Recommended Citation Marcus Reker, Katherine B., ""Can We Do A Happy Musical Next Time?": Navigating Brechtian Tradition and Satirical Comedy Through Hope's Eyes in Urinetown: The usicalM " (2016). Scripps Senior Theses. Paper 876. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/876 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “CAN WE DO A HAPPY MUSICAL NEXT TIME?”: NAVIGATING BRECHTIAN TRADITION AND SATIRICAL COMEDY THROUGH HOPE’S EYES IN URINETOWN: THE MUSICAL BY KATHERINE MARCUS REKER “Nothing is more revolting than when an actor pretends not to notice that he has left the level of plain speech and started to sing.” – Bertolt Brecht SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS GIOVANNI ORTEGA ARTHUR HOROWITZ THOMAS LEABHART RONNIE BROSTERMAN APRIL 22, 2016 II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not be possible without the support of the entire Faculty, Staff, and Community of the Pomona College Department of Theatre and Dance. Thank you to Art, Sherry, Betty, Janet, Gio, Tom, Carolyn, and Joyce for teaching and supporting me throughout this process and my time at Scripps College. Thank you, Art, for convincing me to minor and eventually major in this beautiful subject after taking my first theatre class with you my second year here. -

Autumn 2019 Beechill Bulbs Welcome to Our Autumn 2019 Collection

Autumn 2019 Beechill Bulbs Welcome to our autumn 2019 collection. As always, bursting with colour and ideas to transform your areas into dazzling displayof warmth and vibrance at an otherwise cold and dull time of the year. Biodiversity & Sustainability This subject has gathered significant momentum now with everincreasing interest in more nature friendly varieties - Alliums,Crocus etc., as well as an increasing scrutiny on the methods ofgrowing and harvesting. This is reflected in the ongoing interest in the increasing amount of organic bulb Beechill Bulbs Ltd lines that are now available (pages 110 to 115). Ballyduff Mechanical planting Tullamore The mechanical planter has proven itself to be a worthwhile Co. Offaly companion on any suitable planting project. As a minimum damage, maximum impact method of planting it has P: +353-57-9322956 no match. Suitable for projects of 100m upwards, we’re F: +353-57-9322957 available to come on-site and give you a survey for suitability and a quote there and then. E: [email protected] Keukenhof trip W: www.bulbs.ie Our annual trip to the Keukenhof gardens has proven to be most popular as a training day in relation to the @beechillbulbs plant production and nurseries, as well as a networking opportunity, with some solid connections - even friendships @BeechillBulbs - formed over the years. beechillbulbs Weather Always a topic near the front of any gardeners mind, the Beast from the east wreaked havoc on flowering times and indeed plant health last year, followed by the drought from the south. This impacted on bulb sizes, yields and disease. -

£75,000 Awarded to Browne's Folly Site

Foll- The e-Bulletin of The Folly Fellowship The Folly Fellowship is a Registered Charity No. 1002646 and a Company Limited by Guarantee No. 2600672 Issue 34: £75,000 awarded to January 2011 Browne’s Folly site Upcoming events: 06 March—Annual General Meeting starting at 2.30pm at athford Hill (Wiltshire) is a leased the manor at Monkton Far- East Haddon Village Hall, B haven for some of our rar- leigh in 1842 and used the folly as Northamptonshire. Details est flora and fauna, including the a project for providing employment were enclosed with the Journal White Heleborine and Twayblade during the agricultural depression. and are available from the F/F website www.follies.org.uk Orchid, and for Greater Horseshoe He also improved the condition of and Bechstein‟s Bats. Part of it is the parish roads and built a school 18-19 March—Welsh Week- owned by the Avon Wildlife Trust in the centre of the village where end with visits to Paxton‟s who received this month a grant of he personally taught the girls. Tower, the Cilwendeg Shell House, and the gardens and £75,000 to spend on infrastructure After his death on 2 August grotto at Dolfor. Details from and community projects such as 1851, the manor was leased to a [email protected] the provision of waymark trails and succession of tenants and eventu- information boards telling visitors ally sold to Sir Charles Hobhouse about the site and about its folly. in 1873: his descendants still own The money was awarded from the estate. -

CADW/ICOMOS REGISTER of PARKS and GARDENS of SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST in WALES SITE DOSSIER SITE NAME Hilston Park REF. NO

CADW/ICOMOS REGISTER OF PARKS AND GARDENS OF SPECIAL HISTORIC INTEREST IN WALES SITE DOSSIER SITE NAME Hilston Park REF. NO. PGW (Gt) 22 OS MAP l6l GRID REF. SO 446l87 FORMER COUNTY Gwent UNITARY AUTHORITY Monmouth B.C. COMMUNITY COUNCIL Llangattock-vibon-avel DESIGNATIONS Listed building: Hilston House Grade II National Park AONB SSSI NNR ESA GAM SAM CA SITE EVALUATION Grade II Primary reasons for grading l9th-century park and garden, with some well preserved features, including ornamental lake and folly tower. TYPE OF SITE l9th-century landscape park, pleasure grounds and garden; l9th-century walled kitchen garden, ice-house MAIN PHASES OF CONSTRUCTION c. l840 onwards VISITED BY/DATE Elisabeth Whittle/December l990 HOUSE Name Hilston House Grid ref SO 446l87 Date/style c. l840/neo-classical Brief description Hilston House stands on the top of a ridge to the west of the Monnow valley. There has been a house on the site since at least the l7th century. During the l7th and l8th centuries it was owned by the Needham family. In l838 the house was burnt down and the next owner, Mr. Cave built the present one, which is a large neo-classical, two- storey building. The main front is on the NW, where there is a two- storey portico in the centre. The SE front has a single-storey portico running the length of the front, leading to a conservatory at the NE end. The E wing of the house was added in the early l900s. OUTBUILDINGS Name Coach-house Grid ref SO 445188 Date/style, and brief description The coach-house stands on the NE side of the drive, between the drive and the Home Farm. -

Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This Is an Edited Version of a Previously Published Article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse)

ancient Pterocarya stenoptera (champion), Thuyopsis dolobrata and Phyllocladus alpinus ‘Silver Blades’. We just had time to admire Michelia doltsopa in flower before having to leave this interesting garden. Our final visit was to Fonmom Castle, the home of Sir Brooke Boothby who had very kindly invited us all to lunch. We sat at a long table in a room orig- inally built in 1180, and remodelled in Georgian times with beautiful plaster- work and furnishings. After lunch we had a tour of the garden which is on shallow limestone soil, and at times windswept. We admired a large Fagus syl- vatica f. purpurea planted on the edge of the escarpment in 1818, that had been given buttress walls to hold the soil and roots. There was a small Sorbus domes- tica growing in the lawn and we learnt that this tree is a native in the country nearby. We walked through the closely planted ornamental walled garden into the large productive walled vegetable garden. This final visit was a splen- did ending to our tour, and having thanked our host for his warm hospitality, we said goodbye to fellow members and departed after a memorable four days, so rich in plant content and well organised by our leader Rose Clay. ARBORETUM NEWS Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia (This is an edited version of a previously published article by Jadranka Beresford-Peirse) Vicinis laudor sed aquis et sospite celo Plus placeo et cultu splendidioris heri Haec tibi sunt hominum vestigia certa viator Ars ubi naturam perficit apta rudem. (Trsteno, 1502) The inscription above, with its reference to “the visual traces of the human race” is carved onto a stone in a pergola at the Trsteno Arboretum, Croatia, a place of beauty arising like a phoenix from the ashes of wanton destruction and natural disasters. -

Curses by Graham Nelson

Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Attic, 1993 Out on the Spire adamantine hand Potting Aunt Old Storage Room (1) (6) Room Jemima's Winery Battlements Bell Tower yellow rubber Lair demijohn, nasty-looking red steel wrench, gloves battery, tourist map wishbone D U End Game: Servant's Priest's Airing Room (7) (10) West Side Parish East Side Missed the Attic Hole (3) Roof Cupboard classical Chapel Church Chapel Point iron gothic-looking key, ancient prayer book, old sooty stick dictionary, scarf D D U D U Old Inside End Game: Stone Missed the Furniture Chimney Cupboard cupboard, medicine bottle, painting, skylight, Cross Point gift-wrapped parcel, bird whistle gas mask Dark East Hollow (2) Room Over the Annexe U Public D sepia photograph, East Wing Footpath cupboard nuts cord, flash Library Disused Dead End Storage Observatory Beside the romantic novel, book of Drive Twenties poetry glass ball canvas rucksack Souvenirs Alison's Writing Room (12) Room (11) projector window, mirror Tiny Balcony Curses by Graham Nelson Mildrew Hall Cellars, 1993 Infinity Symbol Cellars (1) Cellar (5) Wine West (3) Cellars (4) robot mouse, vent Hellish Place Hole in Cellars Wall South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Hole in Wall of Cellars South (Mouse Maze), 1993 small brass key Cellars South Curses by Graham Nelson Meldrew Estate Grounds, 1993 Up the Plane To Maze Tree D U Mosaic (2) (17) (23) (29) Garage (35) (38) (39) (40) (41) Behind Heavenly Family Tree Lawn (42) (43) (48) (54) Clearing Summer Place (8) Ornaments big motorised garden roller, -

From Epic to Romance: the Paralysis of the Hero in the Prise D'orange

Minnette Grunmann-Gaudet From Epic to Romance: The Paralysis of the Hero in the Prise d'Orange N HIS Essai de poétique médiévale, Paul Zumthor attempts to establish a basic structural model for the Old French epic, (Schema I I).1 He bases his schema upon a typological classification of the principal characters of the chanson de geste proposed by Pasqualino in 1970. On the primary horizontal axis we find an opposition between good and bad characters, or in socio-religious terms, between Christians and pagans. This axis is broken by secondary diagonal axes which gauge whether individuals change, becoming good by repentance or conversion to Christianity, or bad by political treason or renouncements of the Christian faith. This model clearly illustrates the moral polarities inherent in works such as the Oxford Roland and the Chanson de Guillaume, but does not account for a great number of gestes in which the conflict is between lord and vassal, uncle and nephew, husband and wife, or even two friends. Schema I 'Paul Zumthor, Essai de poétique médiévale (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 1972),p. 326. 22 Grunmann-Gaudet / Paralysis in the Prise d'Orange 23 In a more recent endeavor to define the structure of the Old French epic, P. Van Nuffel develops a similar but more elaborate schema, based upon the Greimasian model for determining deep structures (Schema II).2 Schéma II defense of Christianity defense of Muhammedanism betrayal of Muhammedanism betrayal of Christianity Here the horizontal axes represent the axes of contraries (defense of Christianity vs. defense of Muhammedanism; betrayal of Muhammed- anism vs. -

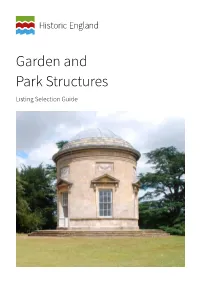

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary

Garden and Park Structures Listing Selection Guide Summary Historic England’s twenty listing selection guides help to define which historic buildings are likely to meet the relevant tests for national designation and be included on the National Heritage List for England. Listing has been in place since 1947 and operates under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. If a building is felt to meet the necessary standards, it is added to the List. This decision is taken by the Government’s Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). These selection guides were originally produced by English Heritage in 2011: slightly revised versions are now being published by its successor body, Historic England. The DCMS‘ Principles of Selection for Listing Buildings set out the over-arching criteria of special architectural or historic interest required for listing and the guides provide more detail of relevant considerations for determining such interest for particular building types. See https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/principles-of- selection-for-listing-buildings. Each guide falls into two halves. The first defines the types of structures included in it, before going on to give a brisk overview of their characteristics and how these developed through time, with notice of the main architects and representative examples of buildings. The second half of the guide sets out the particular tests in terms of its architectural or historic interest a building has to meet if it is to be listed. A select bibliography gives suggestions for further reading. This guide looks at buildings and other structures found in gardens, parks and indeed designed landscapes of all types from the Middle Ages to the twentieth century. -

The Matchmaker Study Guide

The Matchmaker Study Guide The Matchmaker by Thornton Wilder The following sections of this BookRags Literature Study Guide is offprint from Gale's For Students Series: Presenting Analysis, Context, and Criticism on Commonly Studied Works: Introduction, Author Biography, Plot Summary, Characters, Themes, Style, Historical Context, Critical Overview, Criticism and Critical Essays, Media Adaptations, Topics for Further Study, Compare & Contrast, What Do I Read Next?, For Further Study, and Sources. (c)1998-2002; (c)2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Encyclopedia of Popular Fiction: "Social Concerns", "Thematic Overview", "Techniques", "Literary Precedents", "Key Questions", "Related Titles", "Adaptations", "Related Web Sites". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. The following sections, if they exist, are offprint from Beacham's Guide to Literature for Young Adults: "About the Author", "Overview", "Setting", "Literary Qualities", "Social Sensitivity", "Topics for Discussion", "Ideas for Reports and Papers". (c)1994-2005, by Walton Beacham. All other sections in this Literature Study Guide are owned and copyrighted by BookRags, Inc. Contents The Matchmaker Study Guide ..................................................................................................... 1 Contents ..................................................................................................................................... -

The Idea of the Labyrinth

·THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH · THE IDEA OF · THE LABYRINTH from Classical Antiquity through the Middle Ages Penelope Reed Doob CORNELL UNIVERSITY PRESS ITHACA AND LONDON Open access edition funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities/Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. Copyright © 1990 by Cornell University First printing, Cornell Paperbacks, 1992 Second paperback printing 2019 All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. Visit our website at cornellpress.cornell.edu. Printed in the United States of America ISBN 978-0-8014-2393-2 (cloth: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3845-6 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5017-3846-3 (pdf) ISBN 978-1-5017-3847-0 (epub/mobi) Librarians: A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress An open access (OA) ebook edition of this title is available under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0): https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by- nc-nd/4.0/. For more information about Cornell University Press’s OA program or to download our OA titles, visit cornellopen.org. Jacket illustration: Photograph courtesy of the Soprintendenza Archeologica, Milan. For GrahamEric Parker worthy companion in multiplicitous mazes and in memory of JudsonBoyce Allen and Constantin Patsalas Contents List of Plates lX Acknowledgments: Four Labyrinths xi Abbreviations XVll Introduction: Charting the Maze 1 The Cretan Labyrinth Myth 11 PART ONE THE LABYRINTH IN THE CLASSICAL AND EARLY CHRISTIAN PERIODS 1. -

GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2021 YOUNG PLANT ALSTROEMERIA ‘Initicancha Moon’ Hilverdaflorist

GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2021 YOUNG PLANT ALSTROEMERIA ‘Initicancha Moon’ HilverdaFlorist ANTIRRHINUM ‘Drew’s Folly’ Plant Select LAVENDER ‘New Madrid® Purple Star’ GreenFuse Botanicals AQUILEGIA ‘Early Bird Purple Blue’ LUPINUS ‘Staircase Red/White’ GERANIUM pratense ‘Dark Leaf Purple’ PanAm Seed GreenFuse Botanicals ECHINACEA ‘SunSeekers Rainbow’ Innoflora 2021 NEW VARIETIES 2021 NEW VARIETIES GULLEY GREENHOUSE 2020-21 Young Plant Assortment LUPINUS ‘Westcountry Towering Inferno’ Must Have Perennials 2021 CONTENTS HELLO! GENERAL INFORMATION Welcome to the 2020-2021 Gulley Greenhouse Prices, Discounts, Shipping, Young Plant Catalog Minimums, Claims..................2 At Gulley Greenhouse we specialize in custom growing plugs Tray Sizes....................................3 and liners of perennials, herbs, ornamental grasses, and Broker Listing...............................4 specialty annuals. Our passion is to provide finished growers with a wide selection of high quality young plants to choose from. Having been established FEATURED AFFILIATIONS as a family business for over 40 years, we’re proud to consider Featured Programs......................5 (Featured breeders and suppliers whose ourselves connected to the industry. We do our best to stay at the premium plants are included in our program) forefront of the new technology and variety advancements that are being made every year (and every day!) FAIRY FLOWERS® THANK YOU Fairy Flower® Introduction.......... 8 Thanks to all of our customers for your continued support! We Fairy Flower® Varieties............... 8 sincerely appreciate your orders and the confidence you’ve shown (By Common name, including sizes, in our products and company. As always, we strive to produce descriptions & lead times) quality plants perfectly suited for easy production and successful sales to the end consumer. SPECIALTY ANNUALS Annual Introduction......................12 We’re looking forward to another great season, with lots of new varieties to offer and the same quality you’ve come to expect.