TLR4 Genetic Variation Is Associated with Inflammatory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certification of Quality Management System for Medical Laboratories Complying with Medical Laboratory Standard, Ministry of Public Health

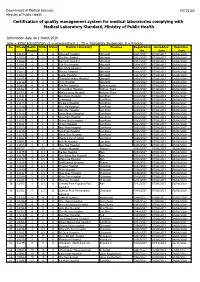

Department of Medical Sciences F0715102 Ministry of Public Health Certification of quality management system for medical laboratories complying with Medical Laboratory Standard, Ministry of Public Health Information date on 1 March 2019 new = initial accreditation, r1 = reassessment 1 , TS = Temporary Suspension, P = Process No. HCode Health RMSc Status Medical Laboratory Province Registration Accredited Expiration Region No. Date Date 1 10673 2 2 r1 Uttaradit Hospital Uttaradit 0001/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 2 11159 2 2 r1 Tha Pla Hospital Uttaradit 0002/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 3 11160 2 2 r1 Nam Pat Hospital Uttaradit 0003/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 4 11161 2 2 r1 Fak Tha Hospital Uttaradit 0004/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 5 11162 2 2 r1 Ban Khok Hospital Uttaradit 0005/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 6 11163 2 2 r1 Phichai Hospital Uttaradit 0006/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 7 11164 2 2 r1 Laplae Hospital Uttaradit 0007/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 8 11165 2 2 r1 ThongSaenKhan Hospital Uttaradit 0008/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 9 11158 2 2 r1 Tron Hospital Uttaradit 0009/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 10 10863 4 4 r1 Pak Phli Hospital Nakhonnayok 0010/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 11 10762 4 4 r1 Thanyaburi Hospital Pathum Thani 0011/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 12 10761 4 4 r1 Klong Luang Hospital Pathum Thani 0012/2557 07/08/2017 06/08/2020 13 11141 1 1 P Ban Hong Hospital LamPhun 0014/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 14 11142 1 1 P Li Hospital LamPhun 0015/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 15 11144 1 1 P Pa Sang Hospital LamPhun 0016/2557 07/08/2014 06/08/2017 -

Aw-Poster-Pongsak Pirom-0629

Poster #0629 HEPATITIS B VIRUS DNA LEVEL CHANGES IN HBeAg+ PREGNANT WOMEN RECEIVING TDF FOR PREVENTION OF MOTHER-TO-CHILD TRANSMISSION IRD-CMU PHPT CROIConference on Retroviruses Nicole Ngo-Giang-Huong1, Nicolas Salvadori2, Woottichai Khamduang2, Tim R. Cressey2, Linda J. Harrison3, Luc Decker1, Camlin Tierney3, Jullapong Achalapong4, and Opportunistic Infections Trudy V. Murphy5, Noele Nelson5, George K. Siberry6, Raymond T. Chung7, Stanislas Pol8, Gonzague Jourdain1, for the iTAP study group 1IRD, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 3Harvard University, Boston, MA, USA, 4Chiangrai Prachanukroh Hospital, Chiang Rai, Thailand, 5CDC, Atlanta, GA, USA, 6USAID, Arlington, VA, USA, 7Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA, 8Cochin Hospital, Paris, France Background HBV DNA load measurements • 12% (19 of 161) did not achieve 5.3 log10 IU/ml at delivery; References • Population: all women assigned to the TDF arm + a randomly the median (range) HBV DNA for these women was 8.3 • High hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA levels and positive hepatitis (7.1 to 9.1) log IU/mL at baseline, 7.4 (4.7 to 8.6) at • Sarin SK, Kumar M, Lau GK, et al. Asian-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on selected subset of 50 women assigned to the placebo arm 10 B e antigen (HBeAg-an indicator of rapid viral replication and 32-weeks, 7.0 (3.9 to 8.5) at 36 weeks and 7.8 (5.3 to 8.9) the management of hepatitis B: a 2015 update. Hepatol Int 2016;10:1-98. • European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address eee, high level of HBV DNA) are the main markers of risk for • Timing: at baseline (28 weeks gestation), at Weeks 32 and at delivery. -

Clinical Epidemiology of 7126 Melioidosis Patients in Thailand and the Implications for a National Notifiable Diseases Surveilla

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Open Forum Infectious Diseases provided by Apollo MAJOR ARTICLE Clinical Epidemiology of 7126 Melioidosis Patients in Thailand and the Implications for a National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System Viriya Hantrakun,1, Somkid Kongyu,2 Preeyarach Klaytong,1 Sittikorn Rongsumlee,1 Nicholas P. J. Day,1,3 Sharon J. Peacock,4 Soawapak Hinjoy,2,5 and Direk Limmathurotsakul1,3,6, 1Mahidol-Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit (MORU), Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand, 2 Epidemiology Division, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, 3 Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health, Nuffield Department of Clinical Medicine, Old Road Campus, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom, 4 Department of Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 5 Office of International Cooperation, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand, and 6 Department of Tropical Hygiene, Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand Background. National notifiable diseases surveillance system (NNDSS) data in developing countries are usually incomplete, yet the total number of fatal cases reported is commonly used in national priority-setting. Melioidosis, an infectious disease caused by Burkholderia pseudomallei, is largely underrecognized by policy-makers due to the underreporting of fatal cases via the NNDSS. Methods. Collaborating with the Epidemiology Division (ED), Ministry of Public Health (MoPH), we conducted a retrospec- tive study to determine the incidence and mortality of melioidosis cases already identified by clinical microbiology laboratories nationwide. A case of melioidosis was defined as a patient with any clinical specimen culture positive for B. -

Saturday 5 September 2015

SATURDAY 5 SEPTEMBER 2015 SATURDAY 5 SEPTEMBER Registration Desk 0745-1730 Registration Desk, SECC for Pre-conference Workshop and Course Participants Location: Hall 4, SECC Group Meeting 1000-1700 AMEE Executive Committee Meeting (Closed Meeting) Location: Green Room 10, Back of Hall 4 AMEE-Essential Skills in Medical Education (ESME) Courses Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0830-1700 ESME – Essential Skills in Medical Education Location: Argyll I, Crowne Plaza 0845-1630 ESMEA – Essential Skills in Medical Education Assessment Location: Argyll III, Crowne Plaza 0845-1630 RESME – Research Essential Skills in Medical Education Location: Argyll II, Crowne Plaza 0845-1700 ESMESim - Essential Skills in Simulation-based Healthcare Instruction Location: Castle II, Crowne Plaza 0900-1700 ESCEPD – Essential Skills in Continuing Education and Professional Development Location: Castle 1, Crowne Plaza 1000-1330 ESCEL – Essential Skills in Computer-Enhanced Learning Location: Carron 2, SECC Course Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0830-1630 ASME-FLAME - Fundamentals of Leadership and Management in Education Location: Castle III, Crowne Plaza Masterclass Pre-registration is essential and lunch will be provided. 0915-1630 MC1 Communication Matters: Demystifying simulation design, debriefing and facilitation practice Kerry Knickle (Standardized Patient Program, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada); Nancy McNaughton, Diana Tabak) University of Toronto, Centre for Research in Education, Standardized -

8Th Thailand Orthopaedic Trauma Annual Congress (TOTAC) 'How

8th Thailand Orthopaedic Trauma Annual Congress (TOTAC) February, 20-22, 2019 @Somdej Phra BorommaRatchathewi Na Si ‘How can we operate as an expert? Pearls and pitfalls’ Racha Hospital, Chonburi TOTAC 2019 “Trauma Night, Dinner Symposium” Feb 20,2019 Room Speaker 18.00-19.00 Fractures of the upper extremity (Thai) Panelist : Chanakarn Phornphutkul Nathapon Chantaraseno Vajarin Phiphobmongkol Surasak Jitprapaikulsarn 18.00-18.15 Fracture-Dislocation of Elbow Sanyakupta Boonperm 18.15-18.30 Neglected fracture of proximal humerus Vantawat Umprai 18.30-18.45 Complex scapular fracture Wichai Termsombatborworn 18.45-19.00 Failed plate of humeral shaft Chonlathan Iamsumang 19.00-20.00 Fractures of the lower extremity (Thai) Panelist : Apipop Kritsaneephaiboon Noratep Kulachote Vajara Phiphobmongkol Pongpol Petchkam 19.00-19.15 Complex fracture of femoral shaft Preecha Bunchongcharoenlert 19.15-19.30 Complex Tibial Plateau Fracture Sasipong Rohitotakarn 19.30-19.45 Posterior Hip Dislocation with Femoral Head Fracture Phoonyathorn Phatthanathitikarn 19.45-20.00 Complex Tibial plafond Fracture Pissanu Reingrittha Page 1 of Feb 21,2019 Room A Speaker Feb 21,2019 Room B Speaker Feb 21,2019 Room C 8.30-10.00 Module 1 : Complex tibial plateau fracture : The art of reconstruction (Thai) Moderator Likit Rugpolmuang Komkrich Wattanapaiboon 8.30-8.40 Initial management and staged approach Puripun Jirangkul 8.40-8.50 Three-column concept and preoperative planning Sorawut Thamyongkit 8.50-9.00 Single or dual implants : how to make a decision? Eakachit Sikarinkul -

Course Description of Bachelor of Science in Paramedicine 1. General Education 1.1 Social Sciences and Humanities MUGE 101 Gener

Course Description of Bachelor of Science in Paramedicine 1. General Education 1.1 Social Sciences and Humanities MUGE 101 General Education for Human Development Pre-requisite - Well-rounded graduates, key issues affecting society and the environment with respect to one’ particular context; holistically integrated knowledge to identify the key factors; speaking and writing to target audiences with respect to objectives; being accountable, respecting different opinions, a leader or a member of a team and work as a team to come up with a systematic basic research-based solution or guidelines to manage the key issues; mindful and intellectual assessment of both positive and negative impacts of the key issues in order to happily live with society and nature SHHU 125 Professional Code of Ethics Pre-requisite - Concepts and ethical principles of people in various professions, journalists, politicians, businessmen, doctors, government officials, policemen, soldiers; ethical problems in the professions and the ways to resolve them SHSS 144 Principles of Communication Pre-requisite - The importance of communication; information transferring, understanding, language usage, behavior of sender and receiver personality and communication; effective communication problems in communication SHSS 250 Public Health Laws and Regulations Pre-requisite - Introduction to law justice procedure; law and regulation for doctor and public health practitioners, medical treatment act, practice of the art of healing act, medical service act, food act, drug act, criminal -

Development of Palliative Care Model Using Thai Traditional Medicine for Treatment of End-Stage Liver Cancer Patients in Thai Traditional Medicine Hospitals

DEVELOPMENT OF PALLIATIVE CARE MODEL USING THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE FOR TREATMENT OF END-STAGE LIVER CANCER PATIENTS IN THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE HOSPITALS By MR. Preecha NOOTIM A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2019 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University - โดย นายปรีชา หนูทิม วทิ ยานิพนธ์น้ีเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตรเภสัชศาสตรดุษฎีบณั ฑิต สาขาวิชาเภสัชศาสตร์สังคมและการบริหาร แบบ 1.1 เภสัชศาสตรดุษฎีบัณฑิต บัณฑิตวิทยาลัย มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร ปีการศึกษา 2562 ลิขสิทธ์ิของบณั ฑิตวทิ ยาลยั มหาวิทยาลัยศิลปากร DEVELOPMENT OF PALLIATIVE CARE MODEL USING THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE FOR TREATMENT OF END-STAGE LIVER CANCER PATIENTS IN THAI TRADITIONAL MEDICINE HOSPITALS By MR. Preecha NOOTIM A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Graduate School, Silpakorn University Academic Year 2019 Copyright of Graduate School, Silpakorn University Title Development of Palliative Care Model Using Thai Traditional Medicine for Treatment of End-stage Liver Cancer Patients in Thai Traditional Medicine Hospitals By Preecha NOOTIM Field of Study (SOCIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE PHARMACY) Advisor Assistant Professor NATTIYA KAPOL , Ph.D. Graduate School Silpakorn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Dean of graduate school (Associate Professor Jurairat Nunthanid, Ph.D.) Approved by Chair -

KHON KAEN Udon Thani 145 X 210 Mm

KHON KAEN Udon Thani 145 x 210 mm. Phrathat Kham Kaen CONTENTS KHON KAEN 8 City Attractions 9 Out-Of-City Attractions 15 Special Events 32 Local Product and Souvenirs 32 Suggested Itinerary 33 Golf Courses 35 Restaurants and Acoomodation 36 Important Telephone Numbers 36 How To Get There 36 UDON THANI 38 City Attractions 39 Out-Of-City Attractions 43 Special Events 51 Local Products and Souvenirs 52 Golf Courses 52 Suggested Itinerary 52 Important Telephone Numbers 55 How To Get There 55 Khon Kaen Khon Kaen Udon Thani Wat Udom Khongkha Khiri Khet Khon kaen Khon Kaen was established as a city over two hundred years ago during the reign of King Rama I, but the natural and historical evidences found in the area indicated that its history dates back much further. The ancient Khmer ruins, traces of human settlement in the prehistoric period, and the fossils of dinosaurs have proven the remarkable history and culture of Khon Kaen since millions of years ago. The strategic location at the heart of the Northeastern region makes Khon Kaen a hub of education, technology, commercial, trans- portation, and handicrafts of the region. One of the most famous crafts that illustrated the time-honoured local wisdom of Thai people is Mudmee silk and the production centre of this exquisite textile is in Khon Kaen. Khon Kaen boasts a diversity of attractions that makes for a memorable holiday where visitors can enjoy exploring a combination of breath taking natural wonders, fascinating historical treasures and cultural heritage, unique way of life, and extraordinary local wisdom. -

วารสารวิจัยและนวัตกรรมทางสุขภาพ Journal of Health Research and Innovation

วิทยาลัยพยาบาลบรมราชชนนี สุราษฎร์ธานี The Conducting of Self-Help Group in Adolescents with Cancer: Nurses’ Roles วารสารวิจัยและนวัตกรรมทางสุขภาพ Journal of Health Research and Innovation ปี ที ่ 3 ฉบับที ่ 2 กรกฎาคม – ธันวาคม 2563 วัตถุประสงค์ 1. เพื่อเผยแพร่ผลงานวิจัย บทความทางวิชาการและนวัตกรรมทางสุขภาพของอาจารย์ บุคลากร นักศึกษา วิทยาลัยพยาบาลบรมราชชนนี สุราษฎร์ธานี ในด้านการแพทย์ การพยาบาล การสาธารณสุข การศึกษาใน สาขาวิทยาศาสตร์สุขภาพ และด้านอื่น ๆ ที่เกี่ยวข้องกับวิทยาศาสตร์สุขภาพ 2. เพื่อเผยแพร่ผลงานวิจัย บทความทางวิชาการและนวัตกรรมทางสุขภาพของบุคลากรทางการแพทย์ นักวิชาการผู้ปฏิบัติงานในศาสตร์ที่เกี่ยวข้องตลอดจนศิษย์เก่า และผู้สนใจ ในด้านการแพทย์ การพยาบาล การสาธารณสุข การศึกษาในสาขาวิทยาศาสตร์สุขภาพ และด้านอื่น ๆ ที่เกี่ยวข้องกับวิทยาศาสตร์สุขภาพ 3. เพื่อสร้างเครือข่ายทางวิชาการทั้งในวิทยาลัยพยาบาลบรมราชชนนี สุราษฎร์ธานี และสถาบันวิชาชีพ ที่เกี่ยวข้อง 4. เพื่อตอบสนองพันธกิจหลักในการสร้างองค์ความรู้และการเผยแพร่ผลงานวิชาการและงานวิจัยของ วิทยาลัยพยาบาลบรมราชชนนี สุราษฎร์ธานี สำนักงำน บรรณาธิการวารสาร วิทยาลัยพยาบาลบรมราชชนนี สุราษฎร์ธานี 56/6 หมู่ 2 ถ.ศรีวิชัย ตาบล มะขามเตี้ย อาเภอเมือง จังหวัดสุราษฎร์ธานี 84000 โทร. 0-7728-7816 ต่อ 218 โทรสาร 0-7727-2571 http://www.bcnsurat.ac.th E-mail: [email protected] พมิ พท์ ี่ โรงพิมพ์เลิศไชย 16/4-6 ถนนไตรอนสุ นธิ์ ตาบลตลาด อาเภอเมืองสุราษฎร์ธานี จังหวัดสุราษฎร์ธานี โทรศัพท์ 0 7727 3973 โทรสาร 0 7729 9521 วารสารวจิ ยั และนวตั กรรมทางสขุ ภาพ เป็นวารสารทมี่ ผี ูท้ รงคณุ วฒุ ติ รวจสอบเนอื้ หาบทความเพอื่ ลงตพี มิ พจ์ า นวน 2 ท่านต่อบทความ และ บทความหรอื ขอ้ คดิ เหน็ ใด ๆ ทปี่ รากฏในวารสารวจิ -

Operation Smile Charity Review Revised 2016

Charity Review Operation Smile Foundation (Thailand) Revised Date: 13/03/2017 Reviewers: Khun Terrence P. Weir,B Ec, CPA (Australia) Manu Pensawangwat, BA Charity Head: Executive Director: Ms. Christina Krause [email protected] Address: 12/2 Soi Methinivate, Sukumvit Soi 24 Klongtoey, Bangkok 10110 Telephone Numbers: +66 2-075-2700-2 Fax Number: +66 2 075-2703 Email Address: [email protected] Website http://www.operationsmile.or.th/ Charity Purpose: Operation Smile Thailand provides free surgeries to repair cleft lip, cleft palate and other facial deformities for children throughout the country. Operation Smile Thailand was registered as a Not-for-profit organization on Feb 11, 2002. Registration as a not-for-profit organization # Kor Tor 1112 Thailand Income Tax Exempt number # 636. Donations to Operation Smile Thailand are tax-deductible for Thai income tax payers. Approximately one in every 700 babies in Thailand is born with a cleft lip or cleft palate. The need for Operation Smile support for Cleft Lip and Cleft Palate surgeries in Thailand is well recognised as over 100 medical professionals in Thailand volunteer their time to perform surgical missions each year. Review Process: We visited the Operation Smile Thailand's office in Bangkok and reviewed the charity activities and discussion in activities details with Mr. Kevin J. Beauvais, Chairman and Ms. Christina Krause, Executive Director and K. Tatpisha Termthavorn, Resources Development Director. We gained a good understanding of the need the surgeries supported by Operation Smile Thailand and can see the high level of professionalism of the staff and transparency of the organisation. Background to the need: Operation Smile is an international non-profit medical charity founded in the U.S. -

Supporting Document Document 1 of CCHD Screening to Reduce

Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health Year of nomination 2018 Supporting document Document 1 of CCHD Screening to Reduce Neonatal Mortality in Thailand Content Page Executive Summary 1 Background, Situation and Problem 5 Evaluation of the Initiative 7 Innovations of the Initiative 14 Implementation of the Initiative 19 Stakeholders 24 Resources 26 Monitoring and Evaluation System 28 Results 30 Obstacles and Solutions 33 Benefits and Mutual Benefit 35 Sustainability and Transferability of the Initiative 39 Success Story 42 Lesson Learned 53 Future Challenges 54 Acknowledgement 55 TITLE: CCHD Screening to Reduce Neonatal Mortality in Thailand 1. Executive Summary 1.1 Problem: According to a 2012 World Bank report, the neonatal mortality rate in Thailand was 8.3 per 1,000 live births. This is much higher compared to Malaysia’s 4 per 1,000 live births and Singapore’s 1 per 1,000 live births. One of the Sustainable Development Goals’ (SDGs) targets is to end preventable deaths of newborns and less than 5 years old age which the success confirms by the index mortality rate of children fewer than 5 and neonatal mortality. Because neonatal mortality is approximate 50% of the mortality of children under 5, so that the newborn babies are vulnerable and need to be given special attention. Thailand has also been working to reducing the neonatal mortality rate as the ultimate goal of Thai National Health Service Plan for newborn. Critical congenital heart diseases (CCHD) are prevailing problem worldwide. In Thailand, approximate 1,000 babies are born annually with CCHD, one important cause of Thai’s neonatal mortality. -

Cotone Congressi Genoa, Italy PROGRAMME

with the endorsement of Regione Liguria 2006 Provincia di Genova University of Genoa Medical Faculty 14-18 September 2006 Cotone Congressi Genoa, Italy PROGRAMME Association for Medical Education in Europe Tay Park House, 484 Perth Road, Dundee DD2 1LR, Scotland, UK Tel: +44 (0)1382 381953 Fax: +44 (0)1382 381987 Email: [email protected] http://www.amee.org Pre-Conference Sessions Thursday 14th and Friday 15th September 2006 Cotone Congressi Scirocco Libeccio Room A Room B Room C Levante Ponente Tramontana Austro Zefi ro Aliseo Module 9, Level 3 Module 9, Level 3 Module 7, Level 3 Module 7, Level 1 Module 7, Ground Module 9, Level 2 Module 9, Level 1 Module 9, Level 2 Module 9, Level 1 Module 9, Level 2 Module 9, Level 2 PCW 3 PCW 4 Meeting PCW 1 PCW 2 th Thursday 14 Challenges to Attracting Personal and Evaluating 1400-1700 hrs the ‘construct’ participation in professional the evidence of validity faculty development development PCW6 PCW 5 PCW 9 PCW 11 ESME Course PCW 10 PCW 15B PCW 7 PCW 8 Meeting th Friday 15 From good ideas to VIEW: Clinical Setting defensible Bedside teaching starts 0900 hrs Using humour to Mini CEX Hands-on approach Collegial 1100-1400 hrs 0930-1230 hrs robust research in competency, training performance is fun tap multiple (repeat workshop) to training SPs dispute medical education and assessment standards on OSCE intelligences PCW6 PCW 5 PCW 14 ESME Course PCW 16 PCW 15A PCW 13 PCW 12 th Friday 15 ...continued ...continued Educational ...continued Active learning Mini CEX Using global Developing 1400-1700 hrs