Simone Caroti – the Generation Starship in Science Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Future David J. Staley

History and Theory,Theme Issue 41 (December 2002), 72-89 ? Wesleyan University 2002 ISSN: 0018-2656 A HISTORYOF THE FUTURE DAVIDJ. STALEY ABSTRACT Does history have to be only about the past? "History"refers to both a subject matterand a thoughtprocess. That thoughtprocess involves raising questions, marshallingevidence, discerningpatterns in the evidence, writing narratives,and critiquingthe narrativeswrit- ten by others. Whatever subject matter they study, all historians employ the thought process of historicalthinking. What if historianswere to extend the process of historicalthinking into the subjectmat- ter domain of the future?Historians would breach one of our profession's most rigid dis- ciplinarybarriers. Very few historiansventure predictions about the future, and those who do are viewed with skepticism by the profession at large. On methodological grounds, most historiansreject as either impractical,quixotic, hubristic,or dangerousany effort to examine the past as a way to make predictionsabout the future. However, where at one time thinking about the future did mean making a scientifical- ly-based prediction,futurists today arejust as likely to think in terms of scenarios.Where a predictionis a definitive statementabout what will be, scenarios are heuristicnarratives that explore alternativeplausibilities of what might be. Scenario writers, like historians, understandthat surprise,contingency, and deviations from the trend line are the rule, not the exception; among scenario writers, context matters.The thought process of the sce- nario method shares many features with historical thinking. With only minimal intellec- tual adjustment,then, most professionally trainedhistorians possess the necessary skills to write methodologicallyrigorous "historiesof the future." History, according to Kevin Reilly, is both a noun and a verb.' By this Reilly means that "history" refers to both a subject matter-a body of knowledge-and a thought process, a disciplined habit of mind. -

Breakthrough Propulsion Study Assessing Interstellar Flight Challenges and Prospects

Breakthrough Propulsion Study Assessing Interstellar Flight Challenges and Prospects NASA Grant No. NNX17AE81G First Year Report Prepared by: Marc G. Millis, Jeff Greason, Rhonda Stevenson Tau Zero Foundation Business Office: 1053 East Third Avenue Broomfield, CO 80020 Prepared for: NASA Headquarters, Space Technology Mission Directorate (STMD) and NASA Innovative Advanced Concepts (NIAC) Washington, DC 20546 June 2018 Millis 2018 Grant NNX17AE81G_for_CR.docx pg 1 of 69 ABSTRACT Progress toward developing an evaluation process for interstellar propulsion and power options is described. The goal is to contrast the challenges, mission choices, and emerging prospects for propulsion and power, to identify which prospects might be more advantageous and under what circumstances, and to identify which technology details might have greater impacts. Unlike prior studies, the infrastructure expenses and prospects for breakthrough advances are included. This first year's focus is on determining the key questions to enable the analysis. Accordingly, a work breakdown structure to organize the information and associated list of variables is offered. A flow diagram of the basic analysis is presented, as well as more detailed methods to convert the performance measures of disparate propulsion methods into common measures of energy, mass, time, and power. Other methods for equitable comparisons include evaluating the prospects under the same assumptions of payload, mission trajectory, and available energy. Missions are divided into three eras of readiness (precursors, era of infrastructure, and era of breakthroughs) as a first step before proceeding to include comparisons of technology advancement rates. Final evaluation "figures of merit" are offered. Preliminary lists of mission architectures and propulsion prospects are provided. -

Available Online Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 2019, 6(11):202-215 Research Article Theoretical

Available online www.jsaer.com Journal of Scientific and Engineering Research, 2019, 6(11):202-215 ISSN: 2394-2630 Research Article CODEN(USA): JSERBR Theoretical Consideration of Star Trek's Space Navigation Yoshinari Minami Advanced Space Propulsion Investigation Laboratory (ASPIL), (Formerly NEC Space Development Division), Japan, E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract As is well known, Star Trek is a masterpiece that has been known worldwide since 1966 as a science fiction set in the famous galaxy universe. A starship (Enterprise) arrives at a star system in a short period of time to a star system that is tens, hundreds and thousands of light years away from the Earth. This method of making a starship reach a distant star system is skillfully expressed in the movie using images. Unfortunately, however, there is no concrete explanation from the physical point of view of the propulsion method of the starship and the principle of warp navigation, that is, the space propulsion theory and the space navigation theory. This paper is an attempt to explain Star Trek's space navigation by applying the hyper-space navigation theory to the field propulsion theory that the author has published in international conferences and peer-reviewed journals since 1993 [1]. Since this paper mainly describes the concept of the principle, most of the mathematical expressions are reduced. See the references for theoretical formulas [1- 6]. Keywords Star Trek; starship; galaxy; space-time; interstellar travel; star flight; navigation; field propulsion; space drive; imaginary time; hyperspace; wormhole; time hole; astrophysics 1. Introduction Space development in the 21st century, unless there is a groundbreaking advance in the space transportation system, the area of activity of human beings will be restricted to the vicinity of the Earth forever and new knowledge cannot be obtained. -

Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: a Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University English Dissertations Department of English Summer 8-7-2012 Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant James H. Shimkus Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss Recommended Citation Shimkus, James H., "Teaching Speculative Fiction in College: A Pedagogy for Making English Studies Relevant." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2012. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/95 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of English at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in English Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TEACHING SPECULATIVE FICTION IN COLLEGE: A PEDAGOGY FOR MAKING ENGLISH STUDIES RELEVANT by JAMES HAMMOND SHIMKUS Under the Direction of Dr. Elizabeth Burmester ABSTRACT Speculative fiction (science fiction, fantasy, and horror) has steadily gained popularity both in culture and as a subject for study in college. While many helpful resources on teaching a particular genre or teaching particular texts within a genre exist, college teachers who have not previously taught science fiction, fantasy, or horror will benefit from a broader pedagogical overview of speculative fiction, and that is what this resource provides. Teachers who have previously taught speculative fiction may also benefit from the selection of alternative texts presented here. This resource includes an argument for the consideration of more speculative fiction in college English classes, whether in composition, literature, or creative writing, as well as overviews of the main theoretical discussions and definitions of each genre. -

The Other in Science Fiction As a Problem for Social Theory 1

doi: 10.17323/1728-192x-2020-4-61-81 The Other in Science Fiction as a Problem for Social Theory 1 Vladimir Bystrov Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] Vladimir Kamnev Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] The paper discusses science fiction literature in its relation to some aspects of the socio- anthropological problem, such as the representation of the Other. Given the diversity of sci-fi genres, a researcher always deals either with the direct representation of the Other (a crea- ture different from an existing human being), or with its indirect, mediated form when the Other, in the original sense of this term, is revealed to the reader or viewer through the optics of some Other World. The article describes two modes of representing the Other by sci-fi literature, conventionally designated as scientist and anti-anthropic. Thescientist representa- tion constructs exclusively-rational premises for the relationship with the Other. Edmund Husserl’s concept of truth, which is the same for humans, non-humans, angels, and gods, can be considered as its historical and philosophical correlate. The anti-anthropic representa- tion, which is more attractive to sci-fi authors, has its origins in the experience of the “dis- enchantment” of the world characteristic of modern man, especially in the tragic feeling of incommensurability of a finite human existence and the infinity of the cosmic abysses. -

Ringworld 01 Ringworld Larry Niven CHAPTER 1 Louis Wu

Ringworld 01 Ringworld Larry Niven CHAPTER 1 Louis Wu In the nighttime heart of Beirut, in one of a row of general-address transfer booths, Louis Wu flicked into reality. His foot-length queue was as white and shiny as artificial snow. His skin and depilated scalp were chrome yellow; the irises of his eyes were gold; his robe was royal blue with a golden steroptic dragon superimposed. In the instant he appeared, he was smiling widely, showing pearly, perfect, perfectly standard teeth. Smiling and waving. But the smile was already fading, and in a moment it was gone, and the sag of his face was like a rubber mask melting. Louis Wu showed his age. For a few moments, he watched Beirut stream past him: the people flickering into the booths from unknown places; the crowds flowing past him on foot, now that the slidewalks had been turned off for the night. Then the clocks began to strike twenty-three. Louis Wu straightened his shoulders and stepped out to join the world. In Resht, where his party was still going full blast, it was already the morning after his birthday. Here in Beirut it was an hour earlier. In a balmy outdoor restaurant Louis bought rounds of raki and encouraged the singing of songs in Arabic and Interworld. He left before midnight for Budapest. Had they realized yet that he had walked out on his own party? They would assume that a woman had gone with him, that he would be back in a couple of hours. But Louis Wu had gone alone, jumping ahead of the midnight line, hotly pursued by the new day. -

A Future History of Water

a future history of water Future History a Duke University Press Durham and London 2019 of Water Andrea Ballestero © 2019 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Typeset in Chaparral Pro by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Ballestero, Andrea, [date] author. Title: A future history of water / Andrea Ballestero. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2019. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2018047202 (print) | lccn 2019005120 (ebook) isbn 9781478004516 (ebook) isbn 9781478003595 (hardcover : alk. paper) isbn 9781478003892 (pbk. : alk. paper) Subjects: lcsh: Water rights—Latin America. | Water rights—Costa Rica. | Water rights—Brazil. | Right to water—Latin America. | Right to water—Costa Rica. | Right to water—Brazil. | Water-supply— Political aspects—Latin America. | Water-supply—Political aspects— Costa Rica. | Water-supply—Political aspects—Brazil. Classification:lcc hd1696.5.l29 (ebook) | lcc hd1696.5.l29 b35 2019 (print) | ddc 333.33/9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047202 Cover art: Nikolaus Koliusis, 360°/1 sec, 360°/1 sec, 47 wratten B, 1983. Photographer: Andreas Freytag. Courtesy of the Daimler Art Collection, Stuttgart. This title is freely available in an open access edition thanks to generous support from the Fondren Library at Rice University. para lioly, lino, rómulo, y tía macha This page intentionally left blank contents ix preface -

Download The

RPG REVIEW Issue #33, December 2016 ISSN 2206-4907 (Online) Transhumanism Interview with Rob Boyle ¼ Designer©s Notes for Cryptomancer¼ Reviews of Eclipse Phase and supplements ¼. A Cure for Aging? GURPS Transhuman ¼ Aeorforms for Blue Planet ¼ APP setting for Big Damn Sci-Fi .. RPGaDay 2016 ¼ Morlocks for GURPS ¼ Doctor Strange and Arrival Movie Reviews ¼ and much more! 1 RPG REVIEW ISSUE 33 December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Administrivia, Coop News, Editorial many contributors p2-6 Interview with Rob Boyle with Rob Boyle p7-10 Transhumanism is Total Nonsense by Karl Brown p11-13 Have We Found A Cure for Aging? by Karl Brown p14-15 Cryptomancer Designer©s Notes by Chad Walker p16-17 Cryptomancer Review by Lev Lafayette p18-19 Transhuman RPG Reviews by Lev Lafayette p20-40 Aeroforms for Blue Planet by Karl Brown p41-42 Sue Gurney, Infomorph Slave Robot by Adrian Smith p43-44 APP for Big Damn Sci-Fi by Nic Moll p45-46 Morlocks for GURPS by Gideon Kalve Jarvis p47-48 RPGaDay 2016 with Lev Lafayette and Karl Brown p49-57 Doctor Strange Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p58-60 Arrival Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p61-63 Next Issue: RPG Design by many people p64 ADMINISTRIVIA RPG Review is a quarterly online magazine which will be available in print version at some stage. All material remains copyright to the authors except for the reprinting as noted in the first sentence. Contact the author for the relevant license that they wish to apply. Various trademarks and images have been used in this magazine of review and criticism. -

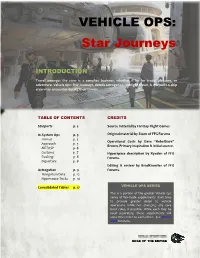

SW Adventure Template

VEHICLE OPS: Star Journeys INTRODUCTION Travel amongst the stars is a complex business, whether it be for trade, pleasure, or adventure. Vehicle Ops: Star Journeys, details astrogation, sublight travel, & starports a ship crew may encounter during their travels. TABLE OF CONTENTS CREDITS Starports p. 2 Source material by Fantasy Flight Games In-System Ops p. 5 Original material by Sturn of FFG Forums Arrival p. 5 Operational Costs by Dave “RebelDave” Approach p. 5 Brown. Primary inspiration & initial source. METOSP p. 6 Customs p. 7 Hyperspace description by Ryoden of FFG Docking p. 8 Forums. Departure p. 8 Editing & review by BradKnowles of FFG Astrogation p. 9 Forums. Navigation Data p. 12 Hyperspace Tricks p. 14 Consolidated Tables p. 17 VEHICLE OPS SERIES This is a portion of the greater Vehicle Ops series of fan-made supplements. Each tries to provide greater detail to vehicle operations while not changing any core book rules, if possible. While each may be used separately, these supplements will sometimes refer to each other. See Sturn’s Stuff for more. EDGE OF THE EMPIRE STARPORTS The most important location for any world within the Star Wars galaxy is its starport. A world’s starport is a nexus of trade and travel. A good port of call is a blessing for any starship crew as a large variety of needed services may be available. The Empire rates starports by a letter grade and a more descriptive title. The five grades of starports are described below using the following descriptors: Docking: Facilities for landing, storage, and unloading cargo. -

Foundation and Empire Kindle

FOUNDATION AND EMPIRE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Isaac Asimov | 304 pages | 01 Apr 1997 | Random House Publishing Group | 9780553293371 | English | New York, NY, United States Foundation and Empire PDF Book I just don't know any of them, except the person who recommended it to me, and she already read it, so. E' un tipo di fantascienza molto suggestiva. The contrast is quite striking. I can write on and on - wish to talk to more Asimovian fans out there. Later writers have added authorized, and unauthorized, tales to the series. Upon approaching the planet, they are drawn inside the Moon's core, where they meet a robot named R. The Mule whose real name is never revealed is a mental freak and possesses the ability to sense and manipulate the emotions of others. This tale was definitely a nod to Belisarius a famous Roman general. His notability and fame increase and he is eventually promoted to First Minister to the Emperor. And by the time Bayta breaks out of that mindset, it is too late. Asimov really blew this one out of the water. Lathan Devers, a native of the Foundation, and Ducem Barr, a patrician from the planet Siwenna, have been "guests" of Bel Riose for several months when it becomes clear that they will soon be treated as enemies, or even be killed. Namespaces Article Talk. I envy you if you have not read Foundation and Empire before or if you have read but possess an even worse memory than mine well, may be the latter not so much. -

Dragon Magazine

Blastoff! The STAR FRONTIERS™ game pro- The STAR FRONTIERS set includes: The work ject was ambitious from the start. The A 16-page Basic Game rule book problems that appear when designing A 64-page Expanded Game rule three complete and detailed alien cul- book tures, a huge frontier area, futuristic is done — A 32-page introductory module, equipment and weapons, and the game Crash on Volturnus rules that make all these elements work now comes 2 full-color maps, 23” x 35” together, were impossible to predict and 10¾" by 17" and not easy to overcome. But the dif- A sheet of 285 full-color counters the fun ficulties were resolved, and the result is a game that lets players enter a truly wide-open space society and explore, The races wander, fight, trade, or adventure A quartet of intelligent, starfaring by Steve Winter through it in the best science-fiction races inhabit the STAR FRONTIERS tradition. rules. New player characters can be D RAGON 7 members of any one of these groups: The adventure ple who had never played a wargame or a Humans (basically just like you With the frontier as its background, role-playing game before. In order to tap and me) the action in a STAR FRONTIERS game this huge market, TSR decided to re- Vrusk (insect-like creatures with focuses on exploring new worlds, dis- structure the STAR FRONTIERS game 10 limbs) covering alien secrets or unearthing an- so it would appeal to people who had Yazirians (ape-like humanoids cient cultures. The rule book includes never seen this type of game. -

Accelerating Martian and Lunar Science Through Spacex Starship Missions

Accelerating Martian and Lunar Science through SpaceX Starship Missions Jennifer L. Heldmann, NASA Ames Research Center, Division of Space Sciences & Astrobiology, Planetary Systems Branch, Moffett Field, CA 94035, 650-604-5530, [email protected] Ali M. Bramson, Purdue University, [email protected] Shane Byrne, University of Arizona, [email protected] Ross Beyer, SETI Institute, [email protected] Peter Carrato, Bechtel Corp., [email protected] Nicholas Cummings, SpaceX, [email protected] Matthew Golombek, Jet Propulsion Lab, [email protected] Tanya Harrison, Outer Space Institute, [email protected] James Head, Brown University, [email protected] Kip Hodges, Arizona State University, [email protected] Keith Kennedy, Bechtel Corp., [email protected] Joe Levy, Colgate University, [email protected] Darlene S.S Lim, NASA Ames Research Center, [email protected] Margarita Marinova, Independent Consultant, [email protected] Alfred McEwen, University of Arizona, [email protected] Gareth Morgan, Planetary Science Institute, [email protected] Asmin Pathare, Planetary Science Institute, [email protected] Nathaniel Putzig, Planetary Science Institute, [email protected] Steve Ruff, Arizona State University, [email protected] Juliana Scheiman, SpaceX, [email protected] Hanna Sizemore, Planetary Science Institute, [email protected] Nathan Williams, Jet Propulsion Lab, [email protected] David Wilson, Bechtel Corp., [email protected] Paul Wooster, SpaceX, [email protected] Kris Zacny, Honeybee Robotics, [email protected] Abstract SpaceX is developing the Starship vehicle for both human and robotic flights to the surface of the Moon and Mars. This two-stage vehicle offers unprecedented payload capacity and the promise of lowering the cost of surface access due to its full reusability.