A Future History of Water

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications

University of Colorado Law School Colorado Law Scholarly Commons Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future 2001 (Summer Conference, June 13-15) 6-14-2001 Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications John E. Thorson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/water-law-and-policy-reform Part of the Administrative Law Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Environmental Policy Commons, Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons, Natural Resources and Conservation Commons, Natural Resources Law Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, State and Local Government Law Commons, Sustainability Commons, Water Law Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Citation Information Thorson, John E., "Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications" (2001). Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future (Summer Conference, June 13-15). https://scholar.law.colorado.edu/water-law-and-policy-reform/10 Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. John E. Thorson, Clarifying State Water Rights and Adjudications, in TWO DECADES OF WATER LAW AND POLICY REFORM: A RETROSPECTIVE AND AGENDA FOR THE FUTURE (Natural Res. Law Ctr., Univ. of Colo. Sch. of Law, 2001). Reproduced with permission of the Getches-Wilkinson Center for Natural Resources, Energy, and the Environment (formerly the Natural Resources Law Center) at the University of Colorado Law School. CLARIFYING STATE WATER RIGHTS AND ADJUDICATIONS John E. Thorson Attorney-at-Law & Water Policy Consultant Oakland, California [Formerly Special Master (1990-2000) Arizona General Stream Adjudication] Two Decades of Water Law and Policy Reform: A Retrospective and Agenda for the Future June 13-15, 2001 NATURAL RESOURCES LAW CENTER University of Colorado School of Law Boulder, Colorado CLARIFYING STATE WATER RIGHTS AND ADJUDICATIONS John E. -

A History of the Future David J. Staley

History and Theory,Theme Issue 41 (December 2002), 72-89 ? Wesleyan University 2002 ISSN: 0018-2656 A HISTORYOF THE FUTURE DAVIDJ. STALEY ABSTRACT Does history have to be only about the past? "History"refers to both a subject matterand a thoughtprocess. That thoughtprocess involves raising questions, marshallingevidence, discerningpatterns in the evidence, writing narratives,and critiquingthe narrativeswrit- ten by others. Whatever subject matter they study, all historians employ the thought process of historicalthinking. What if historianswere to extend the process of historicalthinking into the subjectmat- ter domain of the future?Historians would breach one of our profession's most rigid dis- ciplinarybarriers. Very few historiansventure predictions about the future, and those who do are viewed with skepticism by the profession at large. On methodological grounds, most historiansreject as either impractical,quixotic, hubristic,or dangerousany effort to examine the past as a way to make predictionsabout the future. However, where at one time thinking about the future did mean making a scientifical- ly-based prediction,futurists today arejust as likely to think in terms of scenarios.Where a predictionis a definitive statementabout what will be, scenarios are heuristicnarratives that explore alternativeplausibilities of what might be. Scenario writers, like historians, understandthat surprise,contingency, and deviations from the trend line are the rule, not the exception; among scenario writers, context matters.The thought process of the sce- nario method shares many features with historical thinking. With only minimal intellec- tual adjustment,then, most professionally trainedhistorians possess the necessary skills to write methodologicallyrigorous "historiesof the future." History, according to Kevin Reilly, is both a noun and a verb.' By this Reilly means that "history" refers to both a subject matter-a body of knowledge-and a thought process, a disciplined habit of mind. -

A Buyer's Guide to Montana Water Rights

A Buyer’s Guide To Montana Water Rights By Stan Bradshaw Trout Unlimited, Montana Water Project A Cautionary Tale his tale is based on real events. I’ve just changed the names, details of the water right, the specific facts of the dispute, T and the location to avoid undue embarrassment to anyone. In 2002, Michael Hartman looked at a ranch for sale on a major tributary in the upper Missouri river basin. It was 1100 acres with frontage on a trout stream, and it had an active sprinkler-irrigated hay operation on 160 acres. When Hartmann was negotiating the deal, the realtor produced a water rights document entitled “Statement of Existing Water Right Claim” (“Statement of Claim” for our purposes). It included a water right number, identified a flow rate of 10 cubic feet per second (cfs), and 320 irrigated acres, complete with a legal description of the acres irrigated. It seemed like a great deal—nice property right on a famous trout stream, and a whole lot of water rights to work with. What’s not to like? So he bought it. After moving on to the land, Hartman looked at the acres claimed for irrigation in the Statement of Claim, located the 160 acres that weren’t currently being irrigated, and embarked on plans to start irrigating them. When he walked the land, he didn’t notice any sign of ditches or headgates on the quarter section he wanted to irrigate, but he figured, “Hey, it’s listed on the water right, so I have the water for it.” He approached the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) about cost sharing a new center pivot on the land and putting a pump into the ditch serving the other 160 acres, and they seemed interested. -

The Other in Science Fiction As a Problem for Social Theory 1

doi: 10.17323/1728-192x-2020-4-61-81 The Other in Science Fiction as a Problem for Social Theory 1 Vladimir Bystrov Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] Vladimir Kamnev Doctor of Philosophical Sciences, Professor, Saint Petersburg University Address: Universitetskaya Nabereznaya, 7/9, Saint Petersburg, Russian Federation 199034 E-mail: [email protected] The paper discusses science fiction literature in its relation to some aspects of the socio- anthropological problem, such as the representation of the Other. Given the diversity of sci-fi genres, a researcher always deals either with the direct representation of the Other (a crea- ture different from an existing human being), or with its indirect, mediated form when the Other, in the original sense of this term, is revealed to the reader or viewer through the optics of some Other World. The article describes two modes of representing the Other by sci-fi literature, conventionally designated as scientist and anti-anthropic. Thescientist representa- tion constructs exclusively-rational premises for the relationship with the Other. Edmund Husserl’s concept of truth, which is the same for humans, non-humans, angels, and gods, can be considered as its historical and philosophical correlate. The anti-anthropic representa- tion, which is more attractive to sci-fi authors, has its origins in the experience of the “dis- enchantment” of the world characteristic of modern man, especially in the tragic feeling of incommensurability of a finite human existence and the infinity of the cosmic abysses. -

The Economic Conception of Water

CHAPTER 4 The economic conception of water W. M. Hanemann University of California. Berkeley, USA ABSTRACT: This chapterexplains the economicconception of water -how economiststhink about water.It consistsof two mainsections. First, it reviewsthe economicconcept of value,explains how it is measured,and discusses how this hasbeen applied to waterin variousways. Then it considersthe debate regardingwhether or not watercan, or should,be treatetlas aneconomic commodity, and discussesthe ways in which wateris the sameas, or differentthan, other commodities from aneconomic point of view. While thereare somedistinctive emotive and symbolic featuresof water,there are also somedistinctive economicfeatures that makethe demandand supplyof water different and more complexthan that of most othergoods. Keywords: Economics,value ofwate!; water demand,water supply,water cost,pricing, allocation INTRODUCTION There is a widespread perception among water professionals today of a crisis in water resources management. Water resources are poorly managed in many parts of the world, and many people -especially the poor, especially those living in rural areasand in developing countries- lack access to adequate water supply and sanitation. Moreover, this is not a new problem - it has been recognized for a long time, yet the efforts to solve it over the past three or four decadeshave been disappointing, accomplishing far less than had been expected. In addition, in some circles there is a feeling that economics may be part of the problem. There is a sense that economic concepts are inadequate to the task at hand, a feeling that water has value in ways that economics fails to account for, and a concern that this could impede the formulation of effective approaches for solving the water crisis. -

Download The

RPG REVIEW Issue #33, December 2016 ISSN 2206-4907 (Online) Transhumanism Interview with Rob Boyle ¼ Designer©s Notes for Cryptomancer¼ Reviews of Eclipse Phase and supplements ¼. A Cure for Aging? GURPS Transhuman ¼ Aeorforms for Blue Planet ¼ APP setting for Big Damn Sci-Fi .. RPGaDay 2016 ¼ Morlocks for GURPS ¼ Doctor Strange and Arrival Movie Reviews ¼ and much more! 1 RPG REVIEW ISSUE 33 December 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Administrivia, Coop News, Editorial many contributors p2-6 Interview with Rob Boyle with Rob Boyle p7-10 Transhumanism is Total Nonsense by Karl Brown p11-13 Have We Found A Cure for Aging? by Karl Brown p14-15 Cryptomancer Designer©s Notes by Chad Walker p16-17 Cryptomancer Review by Lev Lafayette p18-19 Transhuman RPG Reviews by Lev Lafayette p20-40 Aeroforms for Blue Planet by Karl Brown p41-42 Sue Gurney, Infomorph Slave Robot by Adrian Smith p43-44 APP for Big Damn Sci-Fi by Nic Moll p45-46 Morlocks for GURPS by Gideon Kalve Jarvis p47-48 RPGaDay 2016 with Lev Lafayette and Karl Brown p49-57 Doctor Strange Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p58-60 Arrival Movie Review by Andrew Moshos p61-63 Next Issue: RPG Design by many people p64 ADMINISTRIVIA RPG Review is a quarterly online magazine which will be available in print version at some stage. All material remains copyright to the authors except for the reprinting as noted in the first sentence. Contact the author for the relevant license that they wish to apply. Various trademarks and images have been used in this magazine of review and criticism. -

Impression Series® Impression Plus Series® Water Filters TABLE of CONTENTS

Impression Series® Impression Plus Series® Water Filters TABLE OF CONTENTS Pre-Installation Instructions for Dealers . 3 Bypass Valve . 4 Installation . 5-7 Programming Procedures . 8 Startup Instructions . 9 Operating Displays and Instructions . 10-11 Replacement Mineral Instructions for Acid Neutralizers . 12 Troubleshooting Guide . 13-16 Replacement Parts . 17-24 Specifications . 25-26 Warranty . 27 Quick Reference Guide . 28 YOUR WATER TEST Hardness _________________________ gpg Iron ______________________________ ppm pH _______________________________ number *Nitrates __________________________ ppm Manganese _______________________ ppm Sulphur ___________________________ yes/no Total Dissolved Solids _______________ *Over 10 ppm may be harmful for human consumption . Water conditioners do not remove nitrates or coliform bacteria, this requires specialized equipment . Your Impression Series water filters are precision built, high quality products . These units will deliver filtered water for many years to come, when installed and operated properly . Please study this manual carefully and understand the cautions and notes before installing . This manual should be kept for future reference . If you have any questions regarding your water softener, contact your local dealer or Water-Right at the following: Water-Right, Inc. 1900 Prospect Court • Appleton, WI 54914 Phone: 920-739-9401 • Fax: 920-739-9406 PRE-INSTALLATION INSTRUCTIONS FOR DEALERS The manufacturer has preset the water treatment unit’s sequence of cycles and cycle times . The dealer should read this page and guide the installer regarding hardness, day override, and time of regeneration, before installation. For the installer, the following must be used: • Program Installer Settings: Day Override (preset to 3 days) and Time of Regeneration (preset to 12 a .m .) • Read Normal Operating Displays • Set Time of Day • Read Power Loss & Error Display For the homeowner, please read sections on Bypass Valve and Operating Displays and Maintenance . -

Simone Caroti – the Generation Starship in Science Fiction

Book Review: The Generation Starship In Science Fiction A Critical History, 1934-2001 Simone Caroti reviewed by John I Davies Dr Simone Caroti has now delivered his presentation on The Generation Starship In Science Fiction to students taking the i4is-led interstellar elective at the International Space University in both 2020 and 2021. Here John Davies reviews his 2011 book based on his PhD work at Purdue University*. Within an overall chronological plan the major themes in Dr Caroti's book seem to me to be - ■ The conflict between the two conceptions of a worldship. Is it a world which happens have an artificial "substrate" or is it a ship with a mission which happens to require a multi-generation crew. ■ How can the vision of dreamers like Tsiolkovsky, J D Bernal and Robert Goddard be made to inspire the source civilisation, for whom this is a massive enterprise, the initial travellers, their intermediate descendants and those who must make a new world at journeys end? ■ And, more practically, how can culture, science and technology be sufficiently preserved over many generations? Opening Chapters The book sees the development of the worldship as a fictional theme in six overlapping eras - the first worldship ideas (not all as fiction), Published: McFarland 2011 mcfarlandbooks.com The Gernsback Era, 1926-1940 , The Campbell Era, 1937-1949, The Image credit: Bill Knapp,Arrival Birth of the Space Age, 1946-1957, The New Wave and Beyond, www.artprize.org/bill-knapp 1957-1979 and The Information Age, 1980-2001. Caroti read a lot of science fiction and speculative non-fiction before beginning his PhD at Purdue University. -

Water: Economics and Policy 2021 – ECI Teaching Module

Water: Economics and Policy By Brian Roach, Anne-Marie Codur and Jonathan M. Harris An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Environmental Issues in Economics Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02155 bu.edu/gdp WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University, 2021. Permission is hereby granted for instructors to copy this module for instructional purposes. Suggested citation: Roach, Brian, Anne-Marie Codur, and Jonathan M. Harris. 2021. “Water: Economics and Policy.” An ECI Teaching Module on Social and Economic Issues, Economics in Context Initiative, Global Development Policy Center, Boston University. Students may also download the module directly from: http://www.bu.edu/eci/education-materials/teaching-modules/ Comments and feedback from course use are welcomed: Economics in Context Initiative Global Development Policy Center Boston University 53 Bay State Road Boston, MA 02215 http://www.bu.edu/eci/ Email: [email protected] NOTE – terms denoted in bold face are defined in the KEY TERMS AND CONCEPTS section at the end of the module. 1 WATER: ECONOMICS AND POLICY TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. GLOBAL SUPPLY AND DEMAND FOR WATER.................................................... 3 1.1 Water Demand, Virtual Water, and Water Footprint ................................................. 8 1.2 Virtual Water Trade ................................................................................................. 11 1.3 Water Footprint the Future of Water: -

Water Right – Conserving Our Water, Preserving Our Environment

WATER RIGHT Conserving Our Water Preserving Our Environment Preface WATER Everywhere Dr. H. Marc Cathey It has many names according to how our eyes experi- and recycle water for our plantings and landscape – ence what it can do. We call it fog, mist, frost, clouds, among which, the lawn is often the most conspicuous sleet, rain, snow, hail and user of water. condensate. It is the one Grasses and the surround- compound that all space ing landscape of trees, explorers search for when shrubs, perennials, food they consider the coloniza- plants, herbs, and native tion of a new planet. It is plants seldom can be left to the dominant chemical in the fickleness of available all life forms and can rainfall. With landscaping make almost 99 percent of estimated to contribute an organism’s weight. It approximately 15 percent is also the solvent in to property values, a We call it fog, mist, frost, clouds, sleet, rain, snow and condensation. which all synthesis of new Water is the earth’s primary chemical under its greatest challenge responsible management compounds––particularly • decision would be to make sugars, proteins, and fats––takes This volume provides the best of all water resources. place. It is also the compound that assurance to everyone that the We are fortunate that the techno- is split by the action of light and quality of our environment will logy of hydroponics, ebb and flow, chlorophyll to release and repeat- not be compromised and we can look forward to years of and drip irrigation have replaced edly recycle oxygen. -

The Local and National Politics of Groundwater Overexploitation

www.water-alternatives.org Volume 11 | Issue 3 Molle, F.; López-Gunn, E. and van Steenbergen, F. 2018. The local and national politics of groundwater overexploitation. Water Alternatives 11(3): 445-457 The Local and National Politics of Groundwater Overexploitation François Molle UMR G-Eau, Institut de Recherche pour le Développement (IRD), Univ Montpellier, France; [email protected] Elena López-Gunn I-CATALIST, S.L., Madrid, Spain; and Visiting Fellow, University of Leeds, UK; [email protected] Frank van Steenbergen MetaMeta Research, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands; [email protected] ABSTRACT: Groundwater overexploitation is a worldwide phenomenon with important consequences and as yet few effective solutions. Work on groundwater governance often emphasises the roles of both formal state- centred policies and tools on the one hand, and self-governance and collective action on the other. Yet, empirically grounded work is limited and scattered, making it difficult to identify and characterise key emerging trends. Groundwater policy making is frequently premised on an overestimation of the power of the state, which is often seen as incapable or unwilling to act and constrained by a myriad of logistical, political and legal issues. Actors on the ground either find many ways to circumvent regulations or develop their own bricolage of patched, often uncoordinated, solutions; whereas in other cases corruption and capture occur, for example in water right trading rules, sometimes with the complicity – even bribing – of officials. Failed regulation has a continued impact on the environment and the crowding out of those lacking the financial means to continue the race to the bottom. Groundwater governance systems vary widely according to the situation, from state-centred governance to co- management and rare instances of community-centred management. -

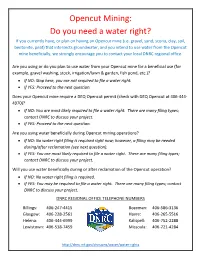

DNRC-Opencut Mining: Do You Need a Water Right?

Opencut Mining: Do you need a water right? If you currently have, or plan on having an Opencut mine (i.e. gravel, sand, scoria, clay, soil, bentonite, peat) that intersects groundwater, and you intend to use water from the Opencut mine beneficially, we strongly encourage you to contact your local DNRC regional office. Are you using or do you plan to use water from your Opencut mine for a beneficial use (for example, gravel washing, stock, irrigation/lawn & garden, fish pond, etc.)? • If NO: Stop here, you are not required to file a water right. • If YES: Proceed to the next question. Does your Opencut mine require a DEQ Opencut permit (check with DEQ Opencut at 406-444- 4970)? • If NO: You are most likely required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. • If YES: Proceed to the next question. Are you using water beneficially during Opencut mining operations? • If NO: No water right filing is required right now; however, a filing may be needed during/after reclamation (see next question). • If YES: You are most likely required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. Will you use water beneficially during or after reclamation of the Opencut operation? • If NO: No water right filing is required. • If YES: You may be required to file a water right. There are many filing types; contact DNRC to discuss your project. DNRC REGIONAL OFFICE TELEPHONE NUMBERS Billings: 406-247-4415 Bozeman: 406-586-3136 Glasgow: 406-228-2561 Havre: 406-265-5516 Helena: 406-444-6999 Kalispell: 406-752-2288 Lewistown: 406-538-7459 Missoula: 406-721-4284 http://dnrc.mt.gov/divisions/water/water-rights .