Disruptors-Dilemma Tivo-1.0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANALYSIS of PROPOSED CONSENT ORDER to AID PUBLIC COMMENT I. Introduction the Federal Trade Commission (“Commission”) Has

ANALYSIS OF PROPOSED CONSENT ORDER TO AID PUBLIC COMMENT I. Introduction The Federal Trade Commission (“Commission”) has accepted for public comment from America Online, Inc. (“AOL”) and Time Warner Inc. (Time Warner”) (collectively “Proposed Respondents”) an Agreement Containing Consent Orders (“Proposed Consent Agreement”), including the Decision and Order (“Proposed Order”). The Proposed Respondents have also reviewed a draft complaint. The Commission has now issued the complaint and an Order to Hold Separate (“Hold Separate Order”). The Proposed Consent Agreement intends to remedy the likely anticompetitive effects arising from the merger of AOL and Time Warner. II. The Parties and the Transaction AOL is the world's leading internet service provider (“ISP”), providing access to the internet for consumers and businesses. AOL operates two ISPs: America Online, with more than 25 million members; and CompuServe, with more than 2.8 million members. AOL also owns several leading Internet products including AOL Instant Messenger, ICQ, Digital City, MapQuest, and MoviePhone; the AOL.com and Netscape.com portals; the Netscape 6, Netscape Navigator and Communicator browsers; and Spinner.com and NullSoft’s Winamp, leaders in Internet music. Time Warner is the nation’s second largest cable television distributor, and one of the leading cable television network providers. Time Warner’s cable systems pass approximately 20.9 million homes and serve approximately 12.6 million cable television subscribers, or approximately 20% of U.S. cable television households. Time Warner, or its principally owned subsidiaries, owns leading cable television networks, such as HBO, Cinemax, CNN, TNT, TBS Superstation, Turner Classic Movies and Cartoon Network. Time Warner also owns, directly or through affiliated businesses, a wide conglomeration of entertainment or media businesses. -

Adolescents, Virtual War, and the Government-Gaming Nexus

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 Why We Still Fight: Adolescents, Virtual War, and the Government Gaming Nexus Margot A. Susca Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION AND INFORMATION WHY WE STILL FIGHT: ADOLESCENTS, VIRTUAL WAR, AND THE GOVERNMENT- GAMING NEXUS By MARGOT A. SUSCA A dissertation submitted to the School of Communication in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2012 Margot A. Susca defended this dissertation on February 29, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Jennifer M. Proffitt Professor Directing Dissertation Ronald L. Mullis University Representative Stephen D. McDowell Committee Member Arthur A. Raney Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my mother iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Jennifer M. Proffitt, Ph.D., for her unending support, encouragement, and guidance throughout this process. I thank her for the endless hours of revision and counsel and for having chocolate in her office, where I spent more time than I would like to admit looking for words of inspiration and motivation. I also would like to thank my committee members, Stephen McDowell, Ph.D., Arthur Raney, Ph.D., and Ronald Mullis, Ph.D., who all offered valuable feedback and reassurance during these last two years. -

CONFIDENTIAL TW 3256902 Page 19 Of26

Page 18 of26 could allow the service provider to boost rates it charges companies for ads AOL, fearing it could be denied access to parts ofthe high-speed Internet market, is currently lobbying regulators to force AT&T Corp. and other cable providers to sell it access to cable data networks at wholesale prices. Microsoft Corp. last year took a $ 5 billion stake in AT&T to ensure it has a place in high-speed cable access. LANGUAGE: English LOAD-DATE: January 10,2000 XINHUA GENERAL NEWS SERVICE THE MATERIALS IN THE XINHUA FILE WERE COMPILED BY THE XINHUA NEWS AGENCY. THESE MATERIALS MAY NOT BE REPUBLISHED WITHOUT THE EXPRESS WRITTEN CONSENT OF THE XINHUA NEWS AGENCY. January 8, 2000, Saturday SECTION: WORLD NEWS LENGTH: 316 words HEADLINE: AOL Demonstrates Internet Service on TV DATELINE: LAS VEGAS, January 7 BODY: Internet giant America Online Inc. (AOL Friday showed a service that lets people use the Internet on their television sets at the ongoing 2000 Consumer Electronics Show (CES) here. The new service, called AOLTV, would be transmitted through cable set-top boxes made by Philips Electronics and Hughes Electronics Corp.'s Direct TV satellite television. "This is the biggest thing for us in 2000," said Carlos A. Silva Jr., vice president ofthe AOL devices division's product studio. "We are aiming on bringing the best ofAOL to the TV set." The new service, which will debut later this year, essentially allows you to surfthe Web with your TV. AOL's service will also allow its members to chat with "buddies," as well as send and receive e-mail. -

A Study on the Web Portal Industry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KDI School Archives A STUDY ON THE WEB PORTAL INDUSTRY: By Chan-Soo Park THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Management, KDI In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF STRATEGY & GLOBAL MANAGEMENT Department of Strategy & International Management 2000 A STUDY ON THE WEB PORTAL INDUSTRY: By Chan-Soo Park THESIS Submitted to School of Public Policy and Management, KDI In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF STRATEGY & GLOBAL MANAGEMENT Department of Strategy & International Management 2000 Professor Seung-Joo Lee 1 ABSTRACT A STUDY ON THE WEB PORTAL INDUSTRY By Chan –Soo Park A portal is a site on the Internet that provides a one-stop experience for Internet users, allowing them to check e-mail, search the Web, and get personalized news and stock quotes. Since 1998, the “portal” has been considered the most successful Internet business model. Portal sites have characteristics such as community facilitated by services, revenue that relies on advertising, a highly competitive market, heavy traffic, and an uncertain business. The world wide portal industry is like a battle zone for America’s top three, broad-based and vertical portals. The Web portal industry is dominated by the “top three portals,” which are AOL, Yahoo and MSN, and “vertical portals” such as Go Network and NBC. The broad-based portals --Lycos, Excite@home, AltaVista and Infoseek—do not lag far behind as major competitors. Many challenges face the three key players and broad-based portals. -

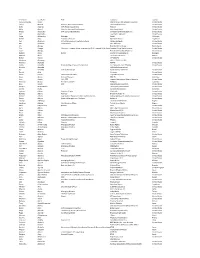

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros

First Name Last Name Title Company Country Anouk Florencia Aaron Warner Bros. International Television United States Carlos Abascal Director, Ole Communications Ole Communications United States Kelly Abcarian SVP, Product Leadership Nielsen United States Mike Abend Director, Business Development New Form Digital United States Friday Abernethy SVP, Content Distribution Univision Communications Inc United States Jack Abernethy Twentieth Television United States Salua Abisambra Manager Salabi Colombia Rafael Aboy Account Executive Newsline Report Argentina Cori Abraham SVP of Development and International Oxygen Network United States Mo Abraham Camera Man VIP Television United States Cris Abrego Endemol Shine Group Netherlands Cris Abrego Chairman, Endemol Shine Americas and CEO, Endemol Shine North EndemolAmerica Shine North America United States Steve Abrego Endemol Shine North America United States Patrícia Abreu Dirctor Upstar Comunicações SA Portugal Manuel Abud TV Azteca SAB de CV Mexico Rafael Abudo VIP 2000 TV United States Abraham Aburman LIVE IT PRODUCTIONS Francine Acevedo NATPE United States Hulda Acevedo Programming Acquisitions Executive A+E Networks Latin America United States Kristine Acevedo All3Media International Ric Acevedo Executive Producer North Atlantic Media LLC United States Ronald Acha Univision United States David Acosta Senior Vice President City National Bank United States Jorge Acosta General Manager NTC TV Colombia Juan Acosta EVP, COO Viacom International Media Networks United States Mauricio Acosta President and CEO MAZDOC Colombia Raul Acosta CEO Global Media Federation United States Viviana Acosta-Rubio Telemundo Internacional United States Camilo Acuña Caracol Internacional Colombia Andrea Adams Director of Sales FilmTrack United States Barbara Adams Founder Broken To Reign TV United States Robin C. Adams Executive In Charge of Content and Production Endavo Media and Communications, Inc. -

Microsofttokentv: TV Meets .NET

Thinkweek MicrosoftTokenTV: TV meets .NET Curtis Wong & Steven Drucker – Next Media Research Introduction This paper discusses an application of existing technology combined in a new way that could be implemented at Microsoft and enhance .NET functionality to broadcast television. The fundamental issue that we wish to discuss is how to fashion the appropriate business strategy to best apply this technology towards enhancing Microsoft’s television platforms. Specifically, TokenTV is an architectural blueprint for a service that would allow convenient remote programming of Personal Video Recorders (PVRs) and delivery of TV related services. Moreover, it is designed in such a way that allows third parties to build upon a platform provided by MS that can greatly increase the influence of the Internet and the .NET approach to the Television space. PVRs are already turning the TV into a device that enables users to watch what they want, when they want it, and less when the content airs. By opening up remote PVR recording to email and the Internet, we can enable PVRs to be remotely directed to record broadcast television programs from anywhere and any device. This is not just about the convenience of remote programming, but enabling everyone to easily record and share television programming without the gating factors of transport bandwidth or copyright infringement issues. TokenTV enables 3rd parties to build business and content services around delivering (via TVTokens) broadcast television programs and related services enabling a new level of consumer convenience. Examples of these will be described later in this document. 11/29/2016 1 Next Media Research Thinkweek Table of Contents The table of contents and other references are hyper linked in the electronic form of this document to related information. -

AOL/TW Petition to Deny

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, DC 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Applications of America Online, Inc. ) CS 00-30 and Time Warner, Inc. for transfers of Control ) PETITION TO DENY of CONSUMERS UNION CONSUMER FEDERATION OF AMERICA MEDIA ACCESS PROJECT and CENTER FOR MEDIA EDUCATION Harold Feld Andrew Jay Schwartzman Cheryl A. Leanza MEDIA ACCESS PROJECT 950 18th St., NW Suite 220 Washington, DC 20006 (202) 232-4300 Counsel for Petitioners April 26, 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTEREST OF PARTIES 3 SUMMARY 4 Policy concerns raised by the aol time warner merger Cross Ownership Between AT&T and AOL In Time Warner Chokehold On Emerging Interactive TV Content Open Access is Even More Critical To A Competitive Broadband Internet in Light of the Proposed Optional Proprietary Access Is Inadequate To Protect The Public Interest ANALYSIS 19 I. INTRODUCTION 21 II. ANTI-COMPETITIVE IMPACTS OF THE INEGRATION OF AT&T AND AOL 22 A Tight Oligopoly Becomes A Duopoly The AOL Time Warner Merger Dramatically Alters The Competitive Landscape For Facilities And Content The AT&T And AOL Deals Have A Pervasive Impact On Industry Structure Specific Vertical Problems Conclusion III. VERTICAL MARKET POWER IN NETWORK INDUSTRIES 49 Theory vs. Reality Commercial interest and public policy flip-flops: Reality vs. Reality The need for open access: Analysis of supply and demand factors Conclusion IV. COMMUNICATIONS INDUSTRIES REQUIRE SPECIAL SAFEGUARDS 76 AGAINST THE ABUSE OF MARKET POWER The Internet Principles The special importance of networks in communications The special role of communications networks in society Conclusion V. DEFINING DISCRIMINATION 100 A. -

Uatabcoe • • TABLE of CONTENTS

Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Applications ofAmerica Online, Inc. ) CS Docket No. 00-30J and Time Warner, Inc. for ) Transfers ofControl ) ) WRITTEN EX PARTE FILING OF THE WALT DISNEY COMPANY THE COMMISSION SHOULD NOT APPROVE THE AOLlfIME WARNER COMBINATION WITHOUT IMPOSING STRONG AND ENFORCEABLE CONDITIONS TO SAFEGUARD AGAINST ANTICOMPETITIVE AND ANTI CONSUMER CONDUCT BY THE MERGED ENTITY Preston Padden Lawrence R. Sidman, Esquire Executive Vice President, Lawrence Duncan, III, Esquire Government Relations Jessica A. Wallace, Esquire The Walt Disney Company VERNER, LIIPFERT, BERNHARD, 1150 17th Street, NW MCPHERSON & HAND, CHARTERED Suite 400 901 15th Street, N.W. Washington, DC 20036 Suite 700 Washington, D.C. 20005 Lou Meisinger Executive Vice President & (202)371-6206 General Counsel The Walt Disney Company Counsel for The Walt Disney Company 5000 South Buena Vista Street Burbank, California 91521 James W. Olson, Esquire Marc G. Schildkraut, Esquire Alan N. Braverman Scott Weisman, Esquire Executive Vice President & . HOWREY, SIMON, ARNOLD & WHITE, LLP General Counsel 1299 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW ABC, Inc. Washington, DC 20004 77 West 66th Street New York, New York 10023 (202)383-7246 OfCounsel for The Walt Disney Company July 25, 2000 No. of CopiQS r8C'd-O _ UatABCOE • • TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1 II. THE INTERN'ET TODAY 7 A. THE INTERNET HAS RAPIDLY BECOME A MAJOR ECONOMIC AND CULTURAL FORCE ................................................................................................................................. 7 B. THE ESSENCE OF THE INTERNET HAs BEEN ITS OPENNESS 8 III. AOL ALREADY IS THE DOMINANT COMPANY ON THE INTERN'ET..•••.••••.•• 9 A. AOL TODAy 9 B. AOL's POSITION Is STRENGTHENING 11 C. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,316,399 B1 Nush (45) Date of Patent: Nov

USOO831 6399B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,316,399 B1 Nush (45) Date of Patent: Nov. 20, 2012 (54) ENABLING PROGRAMMING OF 6,781,608 B1* 8/2004 Crawford ...................... 715/758 2002, 0087661 A1* 7, 2002 Matichuk et al. TO9.218 RECORDINGS 2002/014.4273 A1* 10, 2002 Reto ............................... 725/86 2003/0009766 A1 1/2003 Marolda ......................... 725/97 (75) Inventor: Peter G. Nush, Ashburn, VA (US) 2005/0028208 A1 2/2005 Ellis et al. ....................... 7.25/58 (73) Assignee: AOL Inc., Dulles, VA (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS “What is UltimateTV,” http://www.ultimatetv.com, Sep. 4, 2002, 1 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this page. patent is extended or adjusted under 35 “What is UltimateTV Features.” http://www.ultimatetv.com/ U.S.C. 154(b) by 3837 days. whatis.asp, Sep. 4, 2002, 1 page. About TiVo Inc. TiVo and ZDTV “Get Networked: Will Pursue (21) Appl. No.: 10/259,791 Delivery of Cyber-programming to TiVo's Personal TV Service'. http://www.tivo.com/about/O126336.html, Jan. 20, 1999, 2 pages. (22) Filed: Sep. 30, 2002 SONICblue Inc., “Price reduction and new service option on award 9 winning ReplayTV 4500 Digital Video Recorder!”, www.replaytv. Related U.S. Application Data com, Sep. 4, 2002, 1 page. (60) Provisional application No. 60/361,278, filed on Mar. * cited by examiner 4, 2002. s Primary Examiner — Pankaj Kumar (51) Int. Cl. Assistant Examiner — Charles N Hicks G06F 3/00 (2006.01) (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm — Finnegan, Henderson, G06F I3/00 (2006.01) Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP H04N 5/445 (2011.01) (52) U.S. -

~ ... --- . -- Federal Communications Commission FCC 01-12

DOCKET FILE COPY OR'G'NAl Federal Communicadons Commission FCC Nffif ~1-12 DOH Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington. D.C. 20554 200/ JAN 2'1 .4 1/: 53 In the Ma:ter of ) ) Applications for Consent to the Transfer of ) Control of Licenses and Section 214 ) CS Docket No. 00-30 r Authorizations by Time Warner Inc. and America ) - Online, Inc., Transferors, to AOL Time Warner ) Inc., Transferee ) ) ) MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER Adopted: January 11.2001 Released: January 22. 200 I By the Commission: Chainnan Kennard and Commissioner Ness issuing separate statements; Commissioners Furchtgott-Roth and Powell concurring in part. dissenting in part, and issuing separate statements; Commissioner Tristani issuing a statement at a later date. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION I II. PUBUC INTEREST FRAMEWORK ]9 III. BACKGROllND 27 A. The Applicants 27 B. Other Proceedings Relevant to the Application to Transfer Licenses 47 C. The Merger Transaction and the Application to Transfer Licenses 50 IV. ANALYSIS OF POTENTIAL PUBUC INTEREST HARMS 52 A. High-Speed Internet Access Services 53 I. Background '" 62 ., Discussion 68 3. Conditions 126 B. Instant Messaging and Advanced 1M-Based High-Speed Services 127 I. Background 133 1. Discussion 145 3. Condition 190 -~ ..._---_._-- Federal Communications Commission FCC 01-12 C. Video Programming 200 1. Electronic Programming Guides 203 2. Broadcast Signal Carriage Issues 207 3. Cable Horizontal Ownership Rules 209 D. Interactive Television Services 215 1. Background ; 217 2. Discussion 233 E. Multichannel Video Programming Distribution 240_ I. Common Ownership ofDBS and Cable MVPDs 243 2. Program Access Issues 248 F. -

Content and Broadband and Service... Oh My - Will a United AOL-Time Warner Become the Wicked Witch of the Web, Or Pave a Yellow Brick Road;Note Joseph P

Journal of Legislation Volume 26 | Issue 2 Article 8 5-1-2000 Content and Broadband and Service... Oh My - Will a United AOL-Time Warner Become the Wicked Witch of the Web, or Pave a Yellow Brick Road;Note Joseph P. Reid Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg Recommended Citation Reid, Joseph P. (2000) "Content and Broadband and Service... Oh My - Will a United AOL-Time Warner Become the Wicked Witch of the Web, or Pave a Yellow Brick Road;Note," Journal of Legislation: Vol. 26: Iss. 2, Article 8. Available at: http://scholarship.law.nd.edu/jleg/vol26/iss2/8 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Journal of Legislation at NDLScholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Legislation by an authorized administrator of NDLScholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Content and Broadband and Service ...Oh My! Will a United AOL-Time Warner Become the Wicked Witch of the Web, or Pave a Yellow Brick Road? I. Introduction In early January 2000, computer power America Online announced plans to acquire media giant Time Warner.' Valued between $160 and $180 billion, the proposed merger would be the largest ever.2 Naturally, given the size and influence of the two companies, the fanfare surrounding the move was equally great. America Online's chairman Steve Case proclaimed that the merger would "launch the next Internet revo- lution," while Time Warner chairman Gerald Levine cooed that "[tihese two companies are a natural fit."' 3 Following the announcement, stock prices of both computer and media companies soared as frenzied market-watchers buzzed about what other mergers might ensue.4 In addition, analysts exalted the sense of the proposed union: not only did each company offer what the other most coveted,5 but the terms of the deal also pleased those who believed that internet companies were slightly overvalued.6 Not all reactions to the announcement were equally positive, however, as critics quickly appeared to decry the union. -

The Aol/Time Warner Merger: Competition and Consumer Choice in Broadband Internet Services and Technologies

S. HRG. 106–1003 THE AOL/TIME WARNER MERGER: COMPETITION AND CONSUMER CHOICE IN BROADBAND INTERNET SERVICES AND TECHNOLOGIES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 29, 2000 Serial No. J–106–66 Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 72–845 WASHINGTON : 2001 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 31-AUG-2001 07:16 Sep 08, 2001 Jkt 072845 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 E:\HR\OC\B845.XXX pfrm04 PsN: B845 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah, Chairman STROM THURMOND, South Carolina PATRICK J. LEAHY, Vermont CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa EDWARD M. KENNEDY, Massachusetts ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania JOSEPH R. BIDEN, JR., Delaware JON KYL, Arizona HERBERT KOHL, Wisconsin MIKE DEWINE, Ohio DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California JOHN ASHCROFT, Missouri RUSSELL D. FEINGOLD, Wisconsin SPENCER ABRAHAM, Michigan ROBERT G. TORRICELLI, New Jersey JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York BOB SMITH, New Hampshire MANUS COONEY, Chief Counsel and Staff Director BRUCE A. COHEN, Minority Chief Counsel (II) VerDate 31-AUG-2001 07:16 Sep 08, 2001 Jkt 072845 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 E:\HR\OC\B845.XXX pfrm04 PsN: B845 C O N T E N T S STATEMENTS OF COMMITTEE MEMBERS Page DeWine, Hon. Mike, a U.S. Senator from the State of Ohio ................................ 5 Hatch, Hon.