Halifax Central Library/ Artist Collaboration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

About Nykredit 2011 CSR Report on Financial Sustainability Contents

About Nykredit 2011 CSR Report on Financial Sustainability Contents 2 | Foreword ............................................................................3 Customers ..........................................................................4 Nykredit's activities ........................................................5 Sustainable mortgage lending ........................................5 Customers first ...............................................................6 Sustainable investment ...................................................9 Customer satisfaction ...................................................10 Nykredit's customer ambassador ..................................10 Social responsibility ........................................................12 Environment and climate ..............................................13 The Crystal ...................................................................15 Social initiatives ............................................................16 Sponsorships ................................................................17 The Nykredit Foundation..............................................17 Staff .................................................................................18 Diversity .......................................................................20 Nykredit Health ............................................................21 Staff figures ..................................................................21 Ownership structure and capital policy .........................23 -

D a N S K a M a J 2 0 1 5 Kopenhagen Zelena

KOPENHAGEN ZELENA PRESTOLNICA EVROPE 2014 DANSKA MAJ 2015 Dansko kraljestvo (krajše le Danska) je najstarejša in najmanjša nor- dijska drža- va, ki se nahaja v Skandinaviji v severni Evropi na polotoku vzhodno od Baltske- ga morja in jugozahodno od Severne- ga morja. Vključuje tudi številne otoke severno od Nemčije, na katero meji tudi po kopnem, in Poljske, poleg teh pa še ozemlja na Grenlandiji in Fer- skih otokih, ki so združena pod dansko krono, če- prav uživajo samou- pravo. Le četrtina teh otokov je naseljena. Danska je iz- razito položna dežela. Najvišji vrh je Ejer Bavnehoj, z 173 metri nadmorske višine. Največja reka je Gudena. zanimivosti: - Danska je mati Lego kock. Njihova zgodba se je začela leta 1932 in v več kot 60. letih so prodali čez 320 bilijonov kock, kar pomeni povprečno 56 kock na vsakega prebivalca na svetu. Zabaviščni park Legoland se nahaja v mestu Bil- lund, kjer so zgrajene različne fingure in modeli iz več kot 25 milijonov lego kock. - Danska je najpomembnejša ribiška država v EU. Ribiško ladjevje šteje prib- ližno 2700 ladij. Letni ulov znaša 2.04 miljonov ton. - Danska ima v lasti 4900 otokov. - Najbolj znan Danec je pisatelj Hans Christian Andersen. - Leta 1989 Danska postane prva Ev- ropska država, ki je legalizirala isto- spolne zakone. - Ferski otoki so nekoč pripadali Nor- veški, ki pa jih je izgubila, ko je Norveški kralj v navalu pijanosti izgubil igro pokra proti Danskemu kralju. INFO DEJSTVA O DANSKI: ORGANIZIRANI OGLEDI: Kraljevo geslo: “Božja pomoč, človeška ljubezen, KØBENHAVNS KOMMUNE danska veličina.” GUIDED TOURS OF kraljica: Margareta II. LOW ENERGY BUILDINGS Danska glavno mesto: København ga. -

He Lass I Rar Retro Ros Ecti E

he lass irar Retrorosectie R R University of Colorado, Denver In tandem with the protracted debate over the rami- teoral dislocation and disersion of aearance and cations of the digital inforation technologies for sustance that the lirar for the electronic resent the lirar there has een a surrising surge in the is criticall ased to recoense as the easure of construction of ne liraries oer the course of the its aesthetic success he less the electronic tet is ast tente ears he oerarching intent ehind lie the analogue tet the ore the lirar for the these ne liraries has een to address the secic electronic resent is ished to oer a of su- deands and challenges of the digital age oeer stitution and suleentation hat the electronic the resonses hae not een erel rograatic tet does not a ercetile correlation eteen the and functional or for that aer technological in oundaries of the tets and the hsical roerties of nature n these regards old and ne liraries alie the artifact unerg ie eteen aearance hae resonded and adated in lie anner et in and sustance or else outerfor and innercontent ar contrast to the unctured asonr frae of traditional liraries hat distinguishes the aorit R “There is a small painting by Antonello da Messina which,” Michael of the ne liraries is their aearance as articulated Brawne in introduction to “Libraries, Architecture and Equipment,” tells olues cladded oen entirel in glass us: “shows St. Jerome in his study; the Saint is sitting in an armchair in h for the last to and half decades ereailit front of a sloping desk surrounded on two sides by book shelves” (9) and transarenc of the lirars eterior eneloe (figure 1). -

COP/2015/By Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects Content

global compact/ COP/2015/by schmidt hammer lassen architects Content/ About us/ company profile/ p. 3 Statement of support/CEO Bente Damgaard/ p. 5 The UN Global Compact/ the guiding principles/ p. 6 We support/ selected initiatives/ p.7 Human Resource management/ working with us/ p. 8 A sustainabel agenda/ certified green knowledge/ p. 11 Building Information Modelling/BIM in architecture / p. 12 Quality Assurance/ guidelines and standards/ p. 13 Business Ethics/responsible behaviour/ p. 16 Sustainable architecture/selected projects/ p. 17 The Nordic Built Charter/ transcending conventions/ p. 18 Urban Mountain/Oslo/Norway/ p. 19 International Criminal Court/The Hague/Netherlands/ p. 22 DOKK1/Aarhus/Denmark/ p. 25 Malmö Live/Malmö/Sweden/ p. 28 Green Valley/Shanghai/China/ p. 31 Urban Mountain/Oslo/Norway /2 “We aspire to the highest standard in everything we do. Driven by the vocation that great architecture generates lasting and positive change, we combine intelligent solutions with exceptional experiences that appeal to senses and mind.“ schmidt hammer lassen architects /core values About us/ schmidt hammer lassen architects is an international architecture practice and one of Scandinavia’s Adopting a holistic approach we believe that the basis of sustainable design is the understanding that most recognized, award-winning studios committed to innovative and sustainable design. every component influences the project. We continuously challenge the concept of architecture by adding innovative methodology and technology to classic Scandinavian design traditions. The result Working out of studios located in Aarhus, Copenhagen, London, and Shanghai, the practice provides of this approach is manifested in our wide-ranging architecture portfolio of more than 28 years of suc- skilled architectural services all over the world. -

Pupblic Participant List 25-5-2019.Xlsx

Next Library 2019 - Preliminary list of participants, updated 25 May 2019 Full name Title Institution/company City Country Ahmad Kareem Qatar National Library Doha Qatar National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science Akihiko Murai Dr. and Technology (AIST) Chiba Japan Albert Kivits Director Public Library Eindhoven Eindhoven Public Library Eindhoven Netherlands Aleksandra Kuczmierczyk Mrs Zory Municipal Public Library Zory Poland Aleksandra Zawalska-Hawel Mrs Zory Municipal Public Library Zory Poland Alexandra Müller Zentralbibliothek Zürich Zürich Switzerland Alistair Alexander Mr Tactical Tech Berlin Germany André Wilkens Director European Cultural Foundation European Cultural Foundation Amsterdam Netherlands Andrea Born Muenchner Stadtbibliothek Muenchen Germany Andrew Chanse Executive Director Spokane Public Library Spokane United States Andrew Khoudi PhD Researcher Architect School Aarhus Aarhus Denmark Anette Bjerring Gammelgård Architect Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects Aarhus Denmark Anette Kaffka Aarhus Public Libraries / Next Library Risskov Denmark Anette Mjöberg Library Director Hässleholm Public Library Hässleholm Sweden Angie Myers Library Chief Capacity Officer Charlotte Mecklenburg Library Charlotte United States Anja Flicker Stadtbücherei Würzburg Public Library Wuerzburg Germany Ann Lundborg Utvecklare bibliotek och folkbildning Region Skåne Malmö Sweden Ann Östman Library developer Kultur Gävleborg, Region Gävleborg Gävle Sweden Anna Bröll Head of Innovation and Communication Barcelona Libraries Barcelona Spain Anna -

Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects Company Profile

Architect Biographies schmidt hammer lassen architects Company Profile Schmidt hammer lassen architects is a modern, Danish architectural practice, shaped by the virtues of Scandinavian traditions and orientated towards and working on the international scene. SHL works at the dynamic intersection of the Nordic traditions and the international scene and seeks to influence international architecture. With its projects winning prizes in national and international competitions coupled with the range of its activities, the practice has evolved since its founding in 1986 to become one of Scandinavia’s largest and most respected architectural firms. Since its inception, the company has won more than 145 international and domestic competitions and is the recipient of 86 awards and citations of excellence. The practice has extensive experience in the design of libraries and other public and cultural landmark buildings such as the extension to the Royal Library in Copenhagen (1999), ARoS Museum of Art in Aarhus, Denmark (2004), the Urban Media Space Library in Aarhus and the Halmstad Library in Sweden (2006). The University of Aberdeen New Library is a major British project is currently under construction. Morten Schmidt Design Director Danish Professional Bodies and Education Aarhus School of Architecture, Dept. of Architectural Design, 1976 - 1982 Member Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and ARB Member American Institute of Architects (AIA) Member Danish Association of Architectural Firms (Danske Ark) Member (and former Deputy Chairman) of the Board of Directors of the Architects’ Association of Denmark (AA) Morten Schmidt Member of the Danish Society of Artists under the Academy Council Founding Partner Member of the Academy Council’s external examination board schmidt hammer lassen architects Morten Schmidt, together with Bjarne Hammer and John Lassen, is a founding partner of SHL architects. -

List of Works LABOH.Xlsx

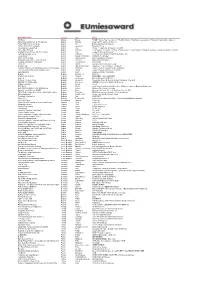

Nominated works Country City Office TID Tower Albania Tirana 51N4E + Ney & Partners engineers + Helidon Kokona + Van Santen & associates + Tirana International Development Marubi National Museum Of Photography Albania Shkodra Casanova+Hernandez Architecten Tiwag KWB Control Center Silz Austria Silz Bechter Zaffignani Architekten Primary School Dorf Lauterach Austria Lauterach Feyferlik / Fritzer Pfauengarten Development Austria Graz Pichler + Traupmann Architekten ZT GmbH Panzerhalle Salzburg Austria Salzburg LP architektur ZT GmbH + hobby a. schuster & maul + cs-architektur Christoph Scheithauer + strobl architekten ZT GmbH Residential Care Home Erika Horn, Andritz Austria Graz Dietger Wissounig Architekten Herberge Refugee Home Austria Innsbruck STUDiO LOiS Barbara Poberschnigg Walch Elias House Moser Austria Neustift im Stubaital Madritsch Pfurtscheller KAMP Office Building Austria Theresienfeld gerner°gerner plus architects Motorway Maintenance Centre Salzburg Austria Salzburg Marte.Marte Architekten Residential building St. Gallenkirch Austria St. Gallenkirch Dorner\Matt Barn Loft Austria Hittisau Georg Bechter Architektur+Design Weingut Högl Austria Spitz an der Donau Ludescher + Lutz, Architeken + Philip Lutz Building. School of Arts and Architecture for Young People Austria Innsbruck studio3 - Institut für experimentelle Architektur Erste Campus Headquarters Building Vienna Austria Vienna Henke Schreieck Architekten ZT GmbH University Graz Austria Graz Gangoly & Kristiner Architekten Belgium Belgium Schaarbeek MSA / V+ Structure -

COP/2014/Schmidt Hammer Lassen Architects

Global Compact/ COP/2014/schmidt hammer lassen architects/ www.shl.dk Content/ About us/ Statement of support/CEO Bente Damgaard The UN Global Compact principles Give support/ Human Resource Management/ Sustainability/ Building Information Modelling/BIM Business Ethics/ Sustainable architecture/Selected projects The Nordic Built Charter/ Urban Mountain/Oslo/Norway Green Valley/Shanghai/China Groendalsvej Zero-energy office building/Aarhus/Denmark Malmö Live/Malmö/Sweden New Hospital/Hvidovre/Denmark Urban Mountain/Oslo/Norway “We design sustainable solutions About us/ that focus on the environment, the user and the overall economy. We constantly challenge the concept of sustainability, because each project must reach new standards.“ schmidt hammer lassen architects /Core values schmidt hammer lassen architects is an international architecture practice and one of Scandinavia’s most recognized, award-winning studios committed to innovative and sustainable design. Working out of studios located in Aarhus, Copenhagen, London, Shanghai and Singapore, the practice provides skilled architectural services all over the world. schmidt hammer lassen architects was founded in Denmark in 1986 and the practice has since grown substantially and employs 160 staff today. schmidt hammer lassen architects upholds a distinguished track record of architecture across a broad spectrum of building typologies and has established a reputation for devising truly sustainable solutions with high emotional value that benefit the environment, society, user, and the overall economy. Adopting a holistic approach we believe that the basis of sustainable design is the understanding that every component influences the project. We continuously challenge the concept of architecture by adding innovative methodology and technology to classic Scandinavian design traditions. The result of this approach is manifested in our wide-ranging architecture portfolio of more than 28 years of successful projects. -

Architecture with Aluminium

forumarchitecture with aluminium volume 27 2014-1 forum Sapa Building System volume 27 2014-1 Forum is published by Sapa Building System AB is the leading Sapa Building System AB. All materials are copyright protected. supplier of aluminium building systems Quotations are allowed provided that the source is stated in the Nordic region. Chief editor Sapa Building System AB develop and market systems for doors, windows, facades, glazed roofs Laurent Heindorff [email protected] and solar shading. We control the entire chain from production of dies, extrusion of profiles, Direct tel: +46 383-942 60 surface treatment, and insulation to stocking system profiles and accessories. We are ISO 9001 certified. Our products are manufactured by independent authorised fabricators. Their commit- Legally responsible Göran Liljenström ment can comprise from know-how, support and consulting to production, delivery, installation, and after-sales service of the products. Address Sapa Building System AB Sapa Building System AB has been active on the market for over forty years. Since then we have 574 81 Vetlanda Tel. +46 383-942 00 developed efficient products and extensive testing has also been carried out to relevant BS and Fax +46 383-76 19 80 EN test standards. Our building system is adapted to the architectural entirety. Four combi- e-mail: [email protected] nable systems can be used to create a variety of applications and functions. With many years Internet: www.sapabuildingsystem.se of experience in developing functional and architectural solutions Sapa offers a flexible Photographs building system with space for new ideas. if not stated otherwise: Hans L. -

The Danish Way. the Rising/Architecture Week 2017 in Aarhus

The Plan Journal 3 (1): 241-257, 2018 doi: 10.15274/tpj.2018.03.01.02 The Danish Way. The Rising/Architecture Week 2017 in Aarhus Maurizio Sabini Conference Report / THEORY ABSTRACT - The Rising/Architecture Week 2017 was held in Aarhus as part of the Aarhus European Capital of Culture 2017 initiatives. The array of conversations, debates, and exchange of ideas generated at Rising 2017 proved once more the vitality and the maturity of Danish design culture. Rooted on a strong Modernist tradition, Danish design culture weaves a savvy mix of promoting and further sharpening its brand, as well as of stimulating thoughtful reflections on relevant disciplinary and societal issues. The conference was intelligently used as vehicle to showcase the good work that is being produced not just in Copenhagen but across Central Denmark and to bring in a diverse pool of international designers, planners, critics, and thinkers. What can be called the Danish Way to design culture offers the opportunity “to rise,” above the conventional and the predictable, for an exciting view over a possible better world. Keywords: Aarhus architecture, Danish design, Rising Architecture Week It is well known how Denmark has increasingly acquired a distinctively rich design culture over the last few decades. The vibrancy and prolificness of the design scene in Copenhagen, spanning from product design to urbanism, is already well appreciated world-wide, up to the point of considering the Danish capital one of the leading design hubs of the world. However, high-level design culture is not only limited to Copenhagen, as demonstrated by the recent Rising/Architecture Week conference held in Aarhus on September 12-14, 2017. -

Architectural Policy

A NATION OF ARCHITECTURE DENMARK SETTINGS FOR LIFE AND GROWTH DANISH ARCHITECTURAL POLICY 2007 THE GOVERNMENT COVER: AROS The Aros Art Museum in Århus is cut through by a large arched/curved spatial progression which connects the streets and squares on each side of the museum like a public pathway. At the same time, the museum’s sculptural stairwell system shows up the museum’s 10 floors. Illustration: schmidt hammer lassen 1. 2. 3. 4. 1. THE METRO IN COPENHAGEN A modern and hi-tech interpretation of the metropolitan transport system. KHR arkitekter AS has designed the stations so that glass pyramids guide daylight to the platforms 18 metres underground. Illustration: Mette Marie Kallehauge 2. ÅRHUS CITY HALL Symbol of early functionalism in Denmark. Arne Jacobsen, Erik Møller and the furniture designer Hans J. Wegner designed everything from the door handles to the tower clock. Illustration: Realdania 3. STATE PRISON IN EAST JUTLAND Friis & Moltke tones down the monumental prison architecture, and instead the buildings snugly adjust to the landscape and the surrounding farm buildings. Illustration: Friis & Moltke 4. GLORUP MANOR HOUSE Erected in the 1590s as a four-wing renaissance manor house. The gardens, in par- ticular, bear witness to the architecture and landscape architecture of their period. Illustration: Andreas Trier Mørch 3 CONTENTS Foreword . page 04 Architecture – settings for life and growth . page 06 01. Greater architectural quality in public construction and development . page 12 02. Promoting private demand for architectural quality . page 16 03. Architectural quality and efficient construction must go hand in hand . page 20 04. -

Press Kit European Union Prize for Contemporary

PRESS KIT EUROPEAN UNION PRIZE FOR CONTEMPORARY ARCHITECTURE MIES VAN DER ROHE AWARD 2017 Contents A. 2017 European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture - Mies van der Rohe Award p. 3 B. The Jury p. 4 C. Sites, villages and cities p. 5 D. 355 nominated works p. 7 E. 40 shortlisted works p. 19 F. 5 finalist works p. 21 G. Calendar p. 25 H. History of the Prize p. 25 I. How the Prize works p. 26 J. 1988-2015 Winners p. 27 K. Organizational Network p. 29 2 A. European Union Prize for Contemporary Architecture Mies van der Rohe Award 2017 Architecture is a slow process that adapts to social, political and economic changes. The Prize takes this statement into account and pursues the following objectives: 1. recognise and commend excellence in European architecture in conceptual, social, cultural, technical and constructive terms 2. highlight the European city as a model for the sustainably smart city, contributing to a sustainable European economy 3. promote transnational architectural commissions throughout Europe and abroad 4. support Emerging architects and Young Talents, as they start out on their careers 5. increase the incorporation of architectural professionals from the EU Member States and those countries that conclude an agreement with the EU 6. cultivate future clients and promoters 7. find business opportunities in a broader global market 8. highlight the involvement of the European Union in supporting architecture as an important element that reflects both the diversity of European architectural expression and its role as a unifying element to define a common European culture.