The Nationalism Project: Competing National Ideologies Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Euskadi-Bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970'S Joakim Lilljegren

BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal Volume 4 | Issue 1 Article 3 October 2016 Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970's Joakim Lilljegren Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga Part of the Basque Studies Commons Recommended Citation Lilljegren, Joakim (2016) "Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish Solidarity with the Basque Independence Movement During the 1970's," BOGA: Basque Studies Consortium Journal: Vol. 4 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. https://doi.org/10.18122/B2MH6N Available at: http://scholarworks.boisestate.edu/boga/vol4/iss1/3 Euskadi-bulletinen: Swedish solidarity with the Basque independence movement during the 1970's Joakim Lilljegren, M.A. In the Swedish national library catalogue Libris, there are some 200 items in the Basque language. Many of them are multilingual and also have text for example in Spanish or French. Only one of them has the rare language combination Swedish and Basque: Euskadi-bulletinen, which was published in 1975–1976 in solidarity with the independence movement in the Basque Country. This short-lived publication and its historical context are described in this article.1 Euskadi-bulletinen was published by Askatasuna ('freedom' in Basque), which described itself as a “committee for solidarity with the Basque people's struggle for freedom and socialism (1975:1, p. 24). “Euskadi” in the bulletin's title did not only refer to the three provinces Araba, Biscay and Gipuzkoa in northern Spain, but also to the neighbouring region Navarre and the three historical provinces Lapurdi, Lower Navarre and Zuberoa in southwestern France. This could be seen directly on the covers which all are decorated with maps including all seven provinces. -

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.)

France and the Dissolution of Yugoslavia Christopher David Jones, MA, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of East Anglia School of History August 2015 © “This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation or extract must include full attribution.” Abstract This thesis examines French relations with Yugoslavia in the twentieth century and its response to the federal republic’s dissolution in the 1990s. In doing so it contributes to studies of post-Cold War international politics and international diplomacy during the Yugoslav Wars. It utilises a wide-range of source materials, including: archival documents, interviews, memoirs, newspaper articles and speeches. Many contemporary commentators on French policy towards Yugoslavia believed that the Mitterrand administration’s approach was anachronistic, based upon a fear of a resurgent and newly reunified Germany and an historical friendship with Serbia; this narrative has hitherto remained largely unchallenged. Whilst history did weigh heavily on Mitterrand’s perceptions of the conflicts in Yugoslavia, this thesis argues that France’s Yugoslav policy was more the logical outcome of longer-term trends in French and Mitterrandienne foreign policy. Furthermore, it reflected a determined effort by France to ensure that its long-established preferences for post-Cold War security were at the forefront of European and international politics; its strong position in all significant international multilateral institutions provided an important platform to do so. -

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

Does Breaking Through the •Œfinal Glass Ceilingâ•Š Really Pave The

Does Breaking Through the “Final Glass Ceiling” Really Pave the Way for Subsequent Women to Become Heads of State? 1 Does Breaking Through the “Final Glass Ceiling” Really Pave the Way for Subsequent Women to Become Heads of State? By Katherine Rocha, Joseph Palazzo, Rebecca Teczar and Roger Clark Rhode Island College Abstract Women’s ascension to the role of national president or prime minister of any country is a relatively new phenomenon in world history. The first woman to break the “final glass ceiling,” Sirinavo Bandaranaike of Ceylon (Sri Lanka today), did it in 1960, just 58 years ago. Since then, the ceiling has been broken in about 83 nations worldwide, but we still know little about what it takes for women to achieve such national leadership roles. Previous research (e.g., Jalalzai, 2013; Skard, 2015) has pointed to the importance of family connections, political turmoil, and the nature of a country’s political system. But only one study (Jalalzai, 2013) provided quantitative, cross-national support for any of these observations. Our paper replicates Jalalzai’s analysis, done using data from the first decade of the twenty-first century, with data from the second decade. We find that there have been dramatic changes over time. We find that family connections are now no more useful for explaining women’s rise to presidencies and prime ministerial positions than men’s; that, in fact, women are now more likely to rise in politically stable nation states than in fragile ones. And, perhaps most importantly, women are much more likely to ascend to the highest positions in countries where they have already broken the “final glass ceiling.” Keywords: final glass ceiling, women presidents, women prime ministers Introduction In a course on the Sociology of Gender we had learned that, while such a ceiling might exist in Following Hillary Clinton’s loss in the 2016 U.S. -

Disproportional Complex States: Scotland and England in the United Kingdom and Slovenia and Serbia Within Yugoslavia

IJournals: International Journal of Social Relevance & Concern ISSN-2347-9698 Volume 6 Issue 5 May 2018 Disproportional Complex States: Scotland and England in the United Kingdom and Slovenia and Serbia within Yugoslavia Author: Neven Andjelic Affiliation: Regent's University London E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT 1. INTRODUCTION This paper provides comparative study in the field of nationalism, political representation and identity politics. It provides comparative analysis of two cases; one in the This paper is reflecting academic curiosity and research United Kingdom during early 21st century and the other in into the field of nationalism, comparative politics, divided Yugoslavia during late 1980s and early 1990s. The paper societies and European integrations in contemporary looks into issues of Scottish nationalism and the Scottish Europe. Referendums in Scotland in 2014 and in National Party in relation to an English Tory government Catalonia in 2017 show that the idea of nation state is in London and the Tory concept of "One Nation". The very strong in Europe despite the unprecedented processes other case study is concerned with the situation in the of integration that undermined traditional understandings former Yugoslavia where Slovenian separatism and their of nation-state, sovereignty and independence. These reformed communists took stand against tendencies examples provide case-studies for study of nation, coming from Serbia to dominate other members of the nationalism and liberal democracy. Exercise of popular federation. The role of state is studied in relation to political will in Scotland invited no violent reactions and federal system and devolved unitary state. There is also proved the case for liberal democracies to solve its issues insight into communist political system and liberal without violence. -

Brave New World: the Correlation of Social Order and the Process Of

Brave New World: The Correlation of Social Order and the Process of Literary Translation by Maria Reinhard A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in German Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2008 ! Maria Reinhard 2008 Author's Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This comparative analysis of four different German-language versions of Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932) shows the correlation between political and socio- cultural circumstances, as well as ideological differences, and translations of the novel. The first German translation was created by Herberth E. Herlitschka in 1932, entitled Welt – Wohin? Two further versions of it were released in 1950 and 1981. In 1978, the East German publisher Das Neue Berlin published a new translation created by Eva Walch, entitled Schöne neue Welt. My thesis focuses on the first translations by both Herlitschka and Walch, but takes into account the others as well. The methodological basis is Heidemarie Salevsky’s tripartite model. With its focus on author and work, commissioning institution and translator, it was developed as a tool to determine the factors influencing the process of literary translation. Within this framework, the translations are contextualized within the cultural and political circumstances of the Weimar and German Democratic Republics, including an historical overview of the two main publishers, Insel and Das Neue Berlin. -

Published As: Jackie Smith and Nicole Doerr, “Democratic Innovation in the U.S

Published as: Jackie Smith and Nicole Doerr, “Democratic Innovation in the U.S. and European Social Forums” in A Handbook of the World Social Forums. J. Smith, S. Byrd, E. Reese, and E. Smythe, Eds. Paradigm Publishers. (2012) Chapter 18 Democratic Innovation in the U.S. and European Social Forums Jackie Smith and Nicole Doerr Democratization is an ongoing, conflict-ridden process, resulting from contestation between social movements and political elites (Markoff 1996; Tilly 1984). The struggle to make elites more accountable to a larger public has produced the democratic institutions with which we are familiar, and it continues to shape and reconfigure these institutions. It also transforms the individuals and organizations involved in social change, generating social movement cultures, norms and practices that evolve over time. In this chapter, we conceptualize the World Social Forum (WSF) process as part of a larger historical struggle over people’s right to participate in decisions that affect their lives. As other contributions to this volume have shown, the WSF has emerged from and brings together a diverse array of social movements, and has become a focal point for contemporary movements struggling against the anti-democratic character of neoliberal globalization. Neoliberalism’s threats to democratic governance result from its expansion of the political and economic authority of international financial institutions like the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization; its hollowing out of national states through privatization, the international debt regime, and international trade policies; its privileging of 1 expert and technocratic knowledge over all other sources of knowledge; and its depoliticization of economic policymaking (Brunelle 2007; Harvey 2005; Markoff 1999; McMichael 2006). -

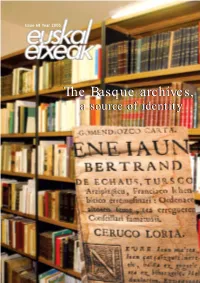

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

Memorial of the Republic of Croatia

INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING THE APPLICATION OF THE CONVENTION ON THE PREVENTION AND PUNISHMENT OF THE CRIME OF GENOCIDE (CROATIA v. YUGOSLAVIA) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF CROATIA APPENDICES VOLUME 5 1 MARCH 2001 II III Contents Page Appendix 1 Chronology of Events, 1980-2000 1 Appendix 2 Video Tape Transcript 37 Appendix 3 Hate Speech: The Stimulation of Serbian Discontent and Eventual Incitement to Commit Genocide 45 Appendix 4 Testimonies of the Actors (Books and Memoirs) 73 4.1 Veljko Kadijević: “As I see the disintegration – An Army without a State” 4.2 Stipe Mesić: “How Yugoslavia was Brought Down” 4.3 Borisav Jović: “Last Days of the SFRY (Excerpts from a Diary)” Appendix 5a Serb Paramilitary Groups Active in Croatia (1991-95) 119 5b The “21st Volunteer Commando Task Force” of the “RSK Army” 129 Appendix 6 Prison Camps 141 Appendix 7 Damage to Cultural Monuments on Croatian Territory 163 Appendix 8 Personal Continuity, 1991-2001 363 IV APPENDIX 1 CHRONOLOGY OF EVENTS1 ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE CHRONOLOGY BH Bosnia and Herzegovina CSCE Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe CK SKJ Centralni komitet Saveza komunista Jugoslavije (Central Committee of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia) EC European Community EU European Union FRY Federal Republic of Yugoslavia HDZ Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (Croatian Democratic Union) HV Hrvatska vojska (Croatian Army) IMF International Monetary Fund JNA Jugoslavenska narodna armija (Yugoslav People’s Army) NAM Non-Aligned Movement NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organisation -

Comparing the Basque Diaspora

COMPARING THE BASQUE DIASPORA: Ethnonationalism, transnationalism and identity maintenance in Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Peru, the United States of America, and Uruguay by Gloria Pilar Totoricagiiena Thesis submitted in partial requirement for Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The London School of Economics and Political Science University of London 2000 1 UMI Number: U145019 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U145019 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Theses, F 7877 7S/^S| Acknowledgments I would like to gratefully acknowledge the supervision of Professor Brendan O’Leary, whose expertise in ethnonationalism attracted me to the LSE and whose careful comments guided me through the writing of this thesis; advising by Dr. Erik Ringmar at the LSE, and my indebtedness to mentor, Professor Gregory A. Raymond, specialist in international relations and conflict resolution at Boise State University, and his nearly twenty years of inspiration and faith in my academic abilities. Fellowships from the American Association of University Women, Euskal Fundazioa, and Eusko Jaurlaritza contributed to the financial requirements of this international travel. -

The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses Summer 7-14-2011 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation Kalyna Macko Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Macko, Kalyna, "The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation" (2011). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 68. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/68 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Macko 1 The Effect of Franco in the Basque Nation By: Kalyna Macko Pell Senior Thesis Primary Advisor: Dr. Jane Bethune Secondary Advisor: Dr. Clark Merrill Macko 2 Macko 3 Thesis Statement: The combined nationalist sentiments and opposition of these particular Basques to the Fascist regime of General Franco explained the violence of the terrorist group ETA both throughout his rule and into the twenty-first century. I. Introduction II. Basque Differences A. Basque Language B. Basque Race C. Conservative Political Philosophy III. The Formation of the PNV A. Sabino Arana y Goiri B. Re-Introduction of the Basque Culture C. The PNV as a Representation of the Basques IV. The Oppression of the Basques A. Targeting the Basques B. Primo de Rivera C. General Francisco Franco D. Bombing of Guernica E. -

Spatialities of Prefigurative Initiatives in Madrid

Spatialities of Prefigurative Initiatives in Madrid María Luisa Escobar Hernández Erasmus Mundus Master Course in Urban Studies [4Cities] Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Dr. Manuel Valenzuela. Professor Emeritus of Human Geography, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Second Reader: Dr. Nick Schuermans. Postdoctoral Researcher, Brussels Centre for Urban Studies. 1st September 2018 Acknowledgments First and foremost I would like to thank all the activists who solidarily shared their stories, experiences, spaces, assemblies and potlucks with me. To Viviana, Alma, Lotta, Araceli, Marta, Chefa, Esther, Cecilia, Daniel Revilla, Miguel Ángel, Manuel, José Luis, Mar, Iñaki, Alberto, Luis Calderón, Álvaro and Emilio Santiago, all my gratitude and appreciation. In a world full of injustice, inequality, violence, oppression and so on, their efforts shed light on the possibilities of building new realities. I would also like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Dr. Manuel Valenzuela for the constant follow-up of this research process, his support in many different ways, his permanent encouragement and his guidance. Likewise, to Dr. Casilda Cabrerizo for her orientation on Madrid’s social movements scene, her expert advice on the initiatives that are being developed in Puente de Vallecas and for providing me with the contacts of some activists. After this intense and enriching two-year Master’s program, I would also like to thank my 4Cities professors. I am particularly grateful to Nick Schuermans who introduced me to geographical thought. To Joshua Grigsby for engaging us to alternative city planning. To Martin Zerlang for his great lectures and his advice at the beginning of this thesis. To Rosa de la Fuente, Marta Domínguez and Margarita Baraño for their effort on showing us the alternative face of Madrid.