PREVENTING TERRORISM? CONFLICT RESOLUTION and NATIONALIST VIOLENCE in the BASQUE COUNTRY Ioannis Tellidis a Thesis Submitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EU and Member States' Policies and Laws on Persons Suspected Of

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT C: CITIZENS’ RIGHTS AND CONSTITUTIONAL AFFAIRS CIVIL LIBERTIES, JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS EU and Member States’ policies and laws on persons suspected of terrorism- related crimes STUDY Abstract This study, commissioned by the European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the European Parliament Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs (LIBE Committee), presents an overview of the legal and policy framework in the EU and 10 select EU Member States on persons suspected of terrorism-related crimes. The study analyses how Member States define suspects of terrorism- related crimes, what measures are available to state authorities to prevent and investigate such crimes and how information on suspects of terrorism-related crimes is exchanged between Member States. The comparative analysis between the 10 Member States subject to this study, in combination with the examination of relevant EU policy and legislation, leads to the development of key conclusions and recommendations. PE 596.832 EN 1 ABOUT THE PUBLICATION This research paper was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs and was commissioned, overseen and published by the Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs. Policy Departments provide independent expertise, both in-house and externally, to support European Parliament committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation -

00 DEMOKRASI K.Indd

Derleyenler Ahmet T. Kuru - Alfred Stepan TÜRKİYE’DE DEMOKRASİ, İSLÂM VE LAİKLİK Derleyenler Ahmet T. Kuru - Alfred Stepan TÜRKİYE’DE DEMOKRASİ, İSLÂM VE LAİKLİK Çeviren Hande Tatoğlu ‹stanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Yay›nlar› 420 Siyaset Bilimi 46 ISBN 978-605-399-279-0 1. Bask› ‹stanbul, Nisan 2013 © Bilgi ‹letiflim Grubu Yay›nc›l›k Müzik Yap›m ve Haber Ajans› Ltd. fiti. Yaz›flma Adresi: ‹nönü Caddesi, No: 43/A Kufltepe fiiflli 34387 ‹stanbul Telefon: 0212 311 61 34 - 311 64 63 / Faks: 0212 297 63 14 • Sertifika No: 11237 www.bilgiyay.com E-posta [email protected] Da€›t›m [email protected] Yay›na Haz›rlayan Cem Tüzün Tasar›m Mehmet Ulusel Dizgi ve Uygulama Maraton Dizgievi • www.dizgievi.com Düzelti Remzi Abbas Dizin Özgür Yıldız Baskı ve Cilt Sena Ofset Ambalaj ve Matbaacılık San. Tic. Ltd. Şti. Litros Yolu 2. Matbaacılar Sitesi B Blok Kat 6 No: 4 NB 7-9-11 Topkapı İstanbul Telefon: 0212 613 03 21 - 613 38 46 / Faks: 0212 613 38 46 • Sertifika No: 12064 ‹stanbul Bilgi University Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data İstanbul Bilgi Üniversitesi Kütüphanesi Kataloglama Bölümü tarafından kataloglanmıştır. Türkiye’de Demokrasi, İslâm ve Laiklik / derleyenler Ahmet t. Kuru, Alfred Stepan; çev. Hande Tatoğlu 228 p. 16x23 cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-605-399-279-0 1. Turkey—Politics and goverment—20th centruy. 2. Turkey—Politics and goverment—21th centruy. 3. Democracy—Turkey. 4. Islam and state—Turkey. 5. Secularism—Turkey. 6. Cultural pluralism—Turkey. I. kuru, Ahmet T. II. Stepan, Alfred C. III. Tatoğlu, Hande. JQ1805. -

The Case of Eta

Cátedra de Economía del Terrorismo UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales DISMANTLING TERRORIST ’S ECONOMICS : THE CASE OF ETA MIKEL BUESA* and THOMAS BAUMERT** *Professor at the Universidad Complutense of Madrid. **Professor at the Catholic University of Valencia Documento de Trabajo, nº 11 – Enero, 2012 ABSTRACT This article aims to analyze the sources of terrorist financing for the case of the Basque terrorist organization ETA. It takes into account the network of entities that, under the leadership and oversight of ETA, have developed the political, economic, cultural, support and propaganda agenda of their terrorist project. The study focuses in particular on the periods 1993-2002 and 2003-2010, in order to observe the changes in the financing of terrorism after the outlawing of Batasuna , ETA's political wing. The results show the significant role of public subsidies in finance the terrorist network. It also proves that the outlawing of Batasuna caused a major change in that funding, especially due to the difficulty that since 2002, the ETA related organizations had to confront to obtain subsidies from the Basque Government and other public authorities. Keywords: Financing of terrorism. ETA. Basque Country. Spain. DESARMANDO LA ECONOMÍA DEL TERRORISMO: EL CASO DE ETA RESUMEN Este artículo tiene por objeto el análisis de las fuentes de financiación del terrorismo a partir del caso de la organización terrorista vasca ETA. Para ello se tiene en cuenta la red de entidades que, bajo el liderazgo y la supervisión de ETA, desarrollan las actividades políticas, económicas, culturales, de propaganda y asistenciales en las que se materializa el proyecto terrorista. -

Country Participants

CIF 2012 Partnership Forum Istanbul, Turkey November 6-7, 2012 List of Participants COUNTRY PARTICIPANTS ARMENIA Tamara Babayan Director Renewable Resources and Energy Efficiency Fund 32, Proshyan 1st lane Yerevan, Armenia Email: [email protected] AUSTRALIA Diane Barclay Director Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) GPO Box 887 Canberra, Australia Email: [email protected] BANGLADESH Md. Sarafat Hossain Khan Project Coordinator Bangladesh Water Development Board Office of the Ganges Barrage Study, 72 Green Road Dhaka, Bangladesh Email: [email protected] BENIN Marcel Comlan Kakpo National Focal Point of Cartagena Protocol of Biosafety and CIF Ministry of Environment, Habitat and Urbanism 04 BP 1005, Cotonou, 01 BP 3621 Littoral- Atlantique, Benin Email: [email protected] BOLIVIA Marcial Berdeja Coordinator Ministry of Environment and Water Calle Capitan Castrillo N 434 La Paz, Bolivia Email: [email protected] Climate Investment Funds – Partnership Forum- Istanbul Turkey Page 1 COUNTRY PARTICIPANTS Jaime Andres Garron Bozo Chief Financing Negotiator Ministry of Development Planning Centro De Communicaciones La Paz, 11 th Floor La Paz, Bolivia Email: [email protected] Roberto Ingemar Salvatierra General Director of Planning Ministry of Environment and Water Calle Capitan Castrillo N 434 La Paz, Bolivia Email: [email protected] BRAZIL Marco Aurelio Dos Santos Araujo Public Policy Specialist Ministry of Finance Esplanada dos Ministerios, Bloco P,Sede 2 Andar, Sala 225 Brasilia/DF, -

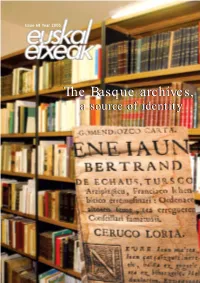

The Basquebasque Archives,Archives, Aa Sourcesource Ofof Identityidentity TABLE of CONTENTS

Issue 68 Year 2005 TheThe BasqueBasque archives,archives, aa sourcesource ofof identityidentity TABLE OF CONTENTS GAURKO GAIAK / CURRENT EVENTS: The Basque archives, a source of identity Issue 68 Year 3 • Josu Legarreta, Basque Director of Relations with Basque Communities. The BasqueThe archives,Basque 4 • An interview with Arantxa Arzamendi, a source of identity Director of the Basque Cultural Heritage Department 5 • The Basque archives can be consulted from any part of the planet 8 • Classification and digitalization of parish archives 9 • Gloria Totoricagüena: «Knowledge of a common historical past is essential to maintaining a people’s signs of identity» 12 • Urazandi, a project shining light on Basque emigration 14 • Basque periodicals published in Venezuela and Mexico Issue 68. Year 2005 ARTICLES 16 • The Basque "Y", a train on the move 18 • Nestor Basterretxea, sculptor. AUTHOR A return traveller Eusko Jaurlaritza-Kanpo Harremanetarako Idazkaritza 20 • Euskaditik: The Bishop of Bilbao, elected Nagusia President of the Spanish Episcopal Conference Basque Government-General 21 • Euskaditik: Election results Secretariat for Foreign Action 22 • Euskal gazteak munduan / Basque youth C/ Navarra, 2 around the world 01007 VITORIA-GASTEIZ Nestor Basterretxea Telephone: 945 01 7900 [email protected] DIRECTOR EUSKAL ETXEAK / ETXEZ ETXE Josu Legarreta Bilbao COORDINATION AND EDITORIAL 24 • Proliferation of programs in the USA OFFICE 26 • Argentina. An exhibition for the memory A. Zugasti (Kazeta5 Komunikazioa) 27 • Impressions of Argentina -

The Changing Nature of the Turkish State Authority for Religious Affairs (ARA) and Turkish Islam in Europe Günter Seufert

Working Paper SWP Working Papers are online publications within the purview of the respective Research Division. Unlike SWP Research Papers and SWP Comments they are not reviewed by the Institute. CENTRE FOR APPLIED TURKEY STUDIES (CATS) | WP NR. 02, JUNE 2020 The changing nature of the Turkish State Authority for Religious Affairs (ARA) and Turkish Islam in Europe Günter Seufert Contents Introduction 4 The umbrella organizations of the Turkish Authority for Religious Affairs in Europe 6 From "partner in integration" to "tool of a foreign power” 7 Definition of terms 9 Historical outline 11 The Authority for Religious Affairs as a product of Turkish secularization: the gradual exclusion of religious discourses and norms from administration and politics 11 The Authority for Religious Affairs as a bone of contention between secular and religious forces 14 Muslim policies beyond traditionalism and Islamism 17 The Authority for Religious Affairs between theological autonomy and political instrumentalization 21 The independence of the Diyanet as a step towards the rehabilitation and empowerment of the Islamic religion in society (and politics?) 21 The independence of the Diyanet as a step towards strengthening the civil character of religion and effectively dealing with worrying currents within national and international Islam 23 The intensified role of the Diyanet in the context of Turkish foreign policy 24 The Diyanet's attitude to subject areas 26 The comments of Diyanet on Fethullah Gülen 26 The Diyanet's Statement on the Ideology of the -

Transnationalization of Turkish Television Series

TRANSNATIONALIZATION OF TURKISH TELEVISION SERIES EDITORS Özlem ARDA, Pınar ASLAN, Constanza MUJICA TRANSNATIONALIZATION OF TURKISH TELEVISION SERIES EDITORS Özlem ARDA Assoc. Prof. Dr., Istanbul University, Faculty of Communication, Radio, Television and Cinema Department, Istanbul, Turkey Pınar ASLAN Assoc. Prof. Dr., Üsküdar University, Faculty of Communication, Public Relations and Publicity, Istanbul, Turkey Constanza MUJICA Assoc. Prof. Dr., Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Facultad de Comunicaciones, Santiago, Chile Published by Istanbul University Press Istanbul University Central Campus IUPress Office, 34452 Beyazıt/Fatih Istanbul - Turkey https://iupress.istanbul.edu.tr Book Title: Transnationalization of Turkish Television Series Editors: Özlem Arda, Pınar Aslan, Constanza Mujica E-ISBN: 978-605-07-0756-4 DOI: 10.26650/B/SS18.2021.004 Istanbul University Publication No: 5277 Published Online in July, 2021 It is recommended that a reference to the DOI is included when citing this work. This work is published online under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC 4.0) https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ This work is copyrighted. Except for the Creative Commons version published online, the legal exceptions and the terms of the applicable license agreements shall be taken into account. iv EDITORS Assoc. Prof. Dr. Özlem ARDA Istanbul University, Faculty of Communication, Radio, Television and Cinema Department, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Pınar ASLAN Üsküdar University, Faculty of Communication, Public Relations and Publicity, Istanbul, Turkey Assoc. Prof. Dr. Constanza MUJICA Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Facultad de Comunicaciones, Santiago, Chile ADVISORY BOARD Prof. Dr. Ergün YOLCU Istanbul University, Faculty of Communication, Istanbul, Turkey Prof. -

Encuentros II-18.Indd

EDITA FUNDACIÓN FERNANDO BUESA BLANCO FUNDAZIOA COLABORA TÍTULO II Encuentros: Fundación Fernando Buesa Blanco Fundazioa / Aldaketa-Cambio por Euskadi Luces y sombras de la disolución de ETA político-militar. II. Topaketak: Fundacion Fernando Buesa Blanco Fundazioa / Aldaketa-Cambio por Euskadi Argi-itzalak ETA politiko-militarra desegitean II Encuentros / II. Topaketak Donostia-San Sebastián, 28 de octubre de 2006 / 2006ko urriak 28 EDITA Fundación Fernando Buesa Blanco Fundazioa y Aldaketa-Cambio por Euskadi FUNDACIÓN FERNANDO BUESA BLANCO FUNDAZIOA Presidenta: Natividad RODRÍGUEZ Calle Postas, 15, 1.º izda. 01001 Vitoria-Gasteiz Secretario General: Emilio GUEVARA Tfno.: 945 234 047 Fax: 945 233 699 Gerente: Milagros GARCÍA DE LA TORRE E-mail: [email protected] Página web: www.fundacionfernandobuesa.com ALDAKETA-CAMBIO POR EUSKADI Presidente: Joseba ARREGI E-mail: [email protected] Secretario: Imanol ZUBERO Página web: www.aldaketa.org Tesorero: Andoni UNZALU TRATAMIENTO EDITORIAL / COORDINACIÓN DE CONTENIDOS DOKU. Servicios de Información y Documentación. Informazio eta Dokumentazio Zerbitzuak DIRECCIÓN CREATIVA / DISEÑO aQ PRODUCCIÓN FRactuaL __ publicaciones__ s.c. Vitoria PREIMPRESIÓN Reproducciones L’arte S.A. IMPRESIÓN Gráficas Santamaría S.A. © De los textos, los autores © De las imágenes, los autores © Fundación Fernando Buesa Blanco Fundazioa ISBN 13: 978-84-611-8536-8 © Aldaketa-Cambio por Euskadi DL: VI-305/07 Índice 1. INTRODUCCIÓN / SARRERA .................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Ethno-Nationalist Terrorism and Political Concessions: a Comparative Analysis of PIRA and ETA Campaigns

Ethno-nationalist Terrorism and Political Concessions: A Comparative Analysis of PIRA and ETA Campaigns By Semir Dzebo Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Nick Sitter Word Count: 17,096 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2017 ABSTRACT Wanting to assess what makes the difference between failure and success in terrorist groups’ campaigns, this research looks at two ethno-nationalist terrorist groups: Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (ETA). This thesis, unlike the majority of contemporary terrorism scholarship focused on religious terrorism, places the spotlight on ethno- nationalist terrorism as it is the type of terrorism most likely to succeed in obtaining political concessions. The research stems from the similarity between the PIRA and ETA cases, despite having ended differently. Employing historical facts and relevant literature, three plausible hypotheses are tested as possible answers to the research question. Each one is based around a different independent variable: goals, support, and strategy. Providing that the hypotheses may all be factors in the outcome, afterwards they are compared and ranked in terms of their explanatory value. Based on the findings, support appears to be the highest explanatory variable. The argument made in this thesis is that the difference in support was likely due to the nature of ethno-nationalist terrorism that is very dependent on its ethnic constituency. Moreover, this thesis argues that what presumably accounts for the difference in support, in these two cases, arises from the nature of violence in which the campaign is embedded. -

Iran: Sponsoring Or Combating Terrorism?

This is a repository copy of Iran: Sponsoring or Combating Terrorism?. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/150747/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Malakoutikhah, Z orcid.org/0000-0001-7804-9881 (2020) Iran: Sponsoring or Combating Terrorism? Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 43 (10). pp. 913-939. ISSN 1057-610X https://doi.org/10.1080/1057610X.2018.1506560 © 2018 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. This is an author produced version of an article published in Studies in Conflict & Terrorism. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Iran: Sponsoring or Combating Terrorism? Zeynab Malakoutikhah PhD, University of Leeds [email protected] Abstract Iran has a longstanding connection with terrorism, in particular after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. It has been recognised as both a victim and state sponsor of terrorism, but has predominantly been accused of supporting terrorism worldwide. -

Counter-Terrorism Reference Curriculum

COUNTER-TERRORISM REFERENCE CURRICULUM CTRC Academic Project Leads & Editors Dr. Sajjan M. Gohel, International Security Director Asia Pacific Foundation Visiting Teacher, London School of Economics & Political Science [email protected] & [email protected] Dr. Peter Forster, Associate Professor Penn State University [email protected] PfPC Reference Curriculum Lead Editors: Dr. David C. Emelifeonwu Senior Staff Officer, Educational Engagements Canadian Defence Academy Associate Professor Royal Military College of Canada Department of National Defence [email protected] Dr. Gary Rauchfuss Director, Records Management Training Program National Archives and Records Administration [email protected] Layout Coordinator / Distribution: Gabriella Lurwig-Gendarme NATO International Staff [email protected] Graphics & Printing — ISBN XXXX 2010-19 NATO COUNTER-TERRORISM REFERENCE CURRICULUM Published May 2020 2 FOREWORD “With guns you can kill terrorists, with education you can kill terrorism.” — Malala Yousafzai, Pakistani activist for female education and Nobel Prize laureate NATO’s counter-terrorism efforts have been at the forefront of three consecutive NATO Summits, including the recent 2019 Leaders’ Meeting in London, with the clear political imperative for the Alliance to address a persistent global threat that knows no border, nationality or religion. NATO’s determination and solidarity in fighting the evolving challenge posed by terrorism has constantly increased since the Alliance invoked its collective defence clause for the first time in response to the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001 on the United States of America. NATO has gained much experience in countering terrorism from its missions and operations. However, NATO cannot defeat terrorism on its own. Fortunately, we do not stand alone. -

Building a Global Terrorism Database

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Building a Global Terrorism Database Author(s): Gary LaFree ; Laura Dugan ; Heather V. Fogg ; Jeffrey Scott Document No.: 214260 Date Received: May 2006 Award Number: 2002-DT-CX-0001 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. BUILDING A GLOBAL TERRORISM DATABASE Dr. Gary LaFree Dr. Laura Dugan Heather V. Fogg Jeffrey Scott University of Maryland April 27, 2006 This project was supported by Grant No. 2002-DT-CX-0001 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. TABLE OF CONTENTS Excutive Summary.................................................................................................. 1 Building a Global Terrorism Database ................................................................... 4 The Original PGIS Database.......................................................................... 6 Methods..................................................................................................................