Towards a History and Aesthetics of Reverse Motion a Dissertation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Came the Dawn : Memories of a Film Pioneer

ICIL M. HEPWORTH a film pioneer The Dawn comes to Flicker Alley Still a familiar figure in Wardour Street, Mr. Cecil Hepworth is a pioneer of British Cinema. In his autobiography he has a fascinating story to tell. They were simpler, sunnier days. Hepworth began in the 'showmanship' period in the late 'nineties, carrying his forty-second films to lecture-halls all over the country, where frenzied audiences demanded their repetition many times at a sitting. From the 'fairground' period he helped nurse the cinema to the time of the great Hepworth Company at its Walton-on- Thames studios. To those studios came famous stage actors, men of mark in many fields, anxious to try the new medium. In those studios many 'stars' of yesterday made world-wide reputations: Alma Taylor, Chrissie White, Gerald Ames, Ronald Colman, Violet Hopson, Stewart Rome, names remembered with deep affection four decades later. From Walton-on-Thames films were dispatched in quantity to the world, even to the United States before the Hollywood era. Conditions, if not primitive, were rudi- mentary in the earlier days; the grandiose notions of the industry today were un- dreamt of; and, most marvellous of all, leading actors and actresses played for as little as half a guinea a day (including fares), and were not averse to doing sorting, filing and running errands in their spare time. [ please turn to back flap MANY 16s ILLUSTRATIONS NET bih'iij II. .niij 37417 NilesBlvd §£g A 510-494-1411 Fremont CA 94536 www.nilesfilmnniseum.org Scanned from the collections of Niles Essanay Silent Film Museum Coordinated by the Media History Digital Library www.mediahistoryproject.org Funded by a donation from Jeff Joseph GAME THE DAWN CECIL M. -

Master Syllabi

PELLISSIPPI STATE TECHNICAL COMMUNITY COLLEGE MASTER SYLLABUS INTRODUCTION TO FILM STUDIES HUM 2810 Class Hours: 3.0 Credit Hours: 3.0 Laboratory Hours: 0.0 Date Revised: Spring 03 Catalog Course Description: An overview of film history using selected world cinema feature films. Basic elements of film expression for understanding and analyzing narrative cinema. Some research is required. Entry Level Standards: Students must be able to read and write at the college level. Prerequisites: None Corequisites: None Textbook(s) and Other Reference Materials Basic to the Course: Text: Understanding Movies Films: in Media Center I. Week/Unit/Topic Basis: Week Topic 1 Note: Different film genres may be studied each semester. The following schedule outlines the classic mystery film genre. Introduction to course and syllabus - Best 100 films- Why study film? Various approaches to film study - Detective/mystery/crime genre in films; Technological factors behind film - Lumiere films (1895) - Melies film (1905); Homework: Read Understanding Movies, pages xi-17 Discuss Film Classification and Shots; Discuss factors in "Formalist Analysis of Classic Film Style "(handout); Screening: Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D.W. Griffith) 18 min.; Homework: Read pages 133-154, "Editing" 2 Discuss Continuity and Cutting; "Hollywood Behind the Badge" (police, crime, mystery genre films); Schedule a research paper; Homework: Read 112-123, "The Moving Camera" Oral research report (D.W. Griffith, Buster Keaton, Charlie Chapman); Discuss 7 Moving Camera Shots, etc.; Screening: -

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality

3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality BY ANDREAS SUDMANN I’ve watched you, Neo. You do not use a computer like a tool. You use it like it was part of yourself. —Morpheus in The Matrix Digital computers, these universal machines, are everywhere; virtually ubiquitous, they surround us, and they do so all the time. They are even inside our bodies. They have become so familiar and so deeply connected to us that we no longer seem to be aware of their presence (apart from moments of interruption, dysfunction—or, in short, events). Without a doubt, computers have become crucial actants in determining our situation. But even when we pay conscious attention to them, we necessarily overlook the procedural (and temporal) operations most central to computation, as these take place at speeds we cannot cognitively capture. How, then, can we describe the affective and temporal experience of digital media, whose algorithmic processes elude conscious thought and yet form the (im)material conditions of much of our life today? In order to address this question, this chapter examines several examples of digital media works (films, games) that can serve as central mediators of the shift to a properly post-cinematic regime, focusing particularly on the aesthetic dimensions of the popular and transmedial “bullet time” effect. Looking primarily at the first Matrix film | 1 3.2 Bullet Time and the Mediation of Post-Cinematic Temporality (1999), as well as digital games like the Max Payne series (2001; 2003; 2012), I seek to explore how the use of bullet time serves to highlight the medial transformation of temporality and affect that takes place with the advent of the digital—how it establishes an alternative configuration of perception and agency, perhaps unprecedented in the cinematic age that was dominated by what Deleuze has called the “movement-image.”[1] 1. -

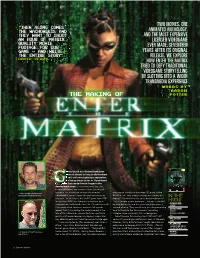

The Making of Enter the Matrix

TWO MOVIES. ONE “THEN ALONG COMES THE WACHOWSKIS AND ANIMATED ANTHOLOGY. THEY WANT TO SHOOT AND THE MOST EXPENSIVE AN HOUR OF MATRIX LICENSED VIDEOGAME QUALITY MOVIE FOOTAGE FOR OUR EVER MADE. SEVENTEEN GAME – AND WRITE YEARS AFTER ITS ORIGINAL THE ENTIRE STORY” RELEASE, WE EXPLORE DAVID PERRY HOW ENTER THE MATRIX TRIED TO DEFY TRADITIONAL VIDEOGAME STORYTELLING BY SLOTTING INTO A WIDER TRANSMEDIA EXPERIENCE Words by Aaron THE MAKING OF Potter ames based on a licence have been around almost as long as the medium itself, with most gaining a reputation for being cheap tie-ins or ill-produced cash grabs that needed much longer in the development oven. It’s an unfortunate fact that, in most instances, the creative teams tasked with » Shiny Entertainment founder and making a fun, interactive version of a beloved working on a really cutting-edge 3D game called former game director David Perry. Hollywood IP weren’t given the time necessary to Sacrifice, so I very embarrassingly passed on the IN THE succeed – to the extent that the ET game from 1982 project.” David chalks this up as being high on his for the Atari 2600 was famously rushed out by a “list of terrible career decisions”, though it wouldn’t KNOW single person and helped cause the US industry crash. be long before he and his team would be given a PUBLISHER: ATARI After every crash, however, comes a full system second chance. They could even use this pioneering DEVELOPER : reboot. And it was during the world’s reboot at the tech to translate the Wachowskis’ sprawling SHINY turn of the millennium, around the time a particular universe more accurately into a videogame. -

Journal of Religion & Society

Journal of Religion & Society Volume 6 (2004) ISSN 1522-5658 David, Mickey Mouse, and the Evolution of an Icon1 Lowell K. Handy, American Theological Library Association Abstract The transformation of an entertaining roguish figure to an institutional icon is investigated with respect to the figures of Mickey Mouse and the biblical King David. Using the three-stage evolution proposed by R. Brockway, the figures of Mickey and David are shown to pass through an initial entertaining phase, a period of model behavior, and a stage as icon. The biblical context for these shifts is basically irretrievable so the extensive materials available for changes in the Mouse provide sufficient information on personnel and social forces to both illuminate our lack of understanding for changes in David while providing some comparative material for similar development. Introduction [1] One can perceive a progression in the development of the figure of David from the rather unsavory character one encounters in the Samuel narratives, through the religious, righteous king of Chronicles, to the messianic abstraction of the Jewish and Christian traditions.2 The movement is a shift from “trickster,” to “Bourgeoisie do-gooder,” to “corporate image” proposed for the evolution of Mickey Mouse by Robert Brockway.3 There are, in fact, several interesting parallels between the portrayals of Mickey Mouse and David, but simply a look at the context that produced the changes in each character may help to understand the visions of David in three surviving biblical textual traditions in light of the adaptability of the Mouse for which there is a great deal more contextual data to investigate. -

Copyright Undertaking

Copyright Undertaking This thesis is protected by copyright, with all rights reserved. By reading and using the thesis, the reader understands and agrees to the following terms: 1. The reader will abide by the rules and legal ordinances governing copyright regarding the use of the thesis. 2. The reader will use the thesis for the purpose of research or private study only and not for distribution or further reproduction or any other purpose. 3. The reader agrees to indemnify and hold the University harmless from and against any loss, damage, cost, liability or expenses arising from copyright infringement or unauthorized usage. IMPORTANT If you have reasons to believe that any materials in this thesis are deemed not suitable to be distributed in this form, or a copyright owner having difficulty with the material being included in our database, please contact [email protected] providing details. The Library will look into your claim and consider taking remedial action upon receipt of the written requests. Pao Yue-kong Library, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hung Hom, Kowloon, Hong Kong http://www.lib.polyu.edu.hk WAR AND WILL: A MULTISEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF METAL GEAR SOLID 4 CARMAN NG Ph.D The Hong Kong Polytechnic University 2017 The Hong Kong Polytechnic University Department of English War and Will: A Multisemiotic Analysis of Metal Gear Solid 4 Carman Ng A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy September 2016 For Iris and Benjamin, my parents and mentors, who have taught me the courage to seek knowledge and truths among warring selves and thoughts. -

PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (Epub)

POST-CINEMA: THEORIZING 21ST-CENTURY FILM, edited by Shane Denson and Julia Leyda, is published online and in e-book formats by REFRAME Books (a REFRAME imprint): http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post- cinema. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online) ISBN 978-0-9931996-3-9 (PDF) ISBN 978-0-9931996-4-6 (ePUB) Copyright chapters © 2016 Individual Authors and/or Original Publishers. Copyright collection © 2016 The Editors. Copyright e-formats, layouts & graphic design © 2016 REFRAME Books. The book is shared under a Creative Commons license: Attribution / Noncommercial / No Derivatives, International 4.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Suggested citation: Shane Denson & Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). REFRAME Books Credits: Managing Editor, editorial work and online book design/production: Catherine Grant Book cover, book design, website header and publicity banner design: Tanya Kant (based on original artwork by Karin and Shane Denson) CONTACT: [email protected] REFRAME is an open access academic digital platform for the online practice, publication and curation of internationally produced research and scholarship. It is supported by the School of Media, Film and Music, University of Sussex, UK. Table of Contents Acknowledgements.......................................................................................vi Notes On Contributors.................................................................................xi Artwork…....................................................................................................xxii -

Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films

Gesticulated Shakespeare: Gesture and Movement in Silent Shakespeare Films Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Rebecca Collins, B.A. Graduate Program in Theatre The Ohio State University 2011 Thesis Committee: Alan Woods, Advisor Janet Parrott Copyright by Jennifer Rebecca Collins 2011 Abstract The purpose of this study is to dissect the gesticulation used in the films made during the silent era that were adaptations of William Shakespeare's plays. In particular, this study investigates the use of nineteenth and twentieth century established gesture in the Shakespearean film adaptations from 1899-1922. The gestures described and illustrated by published gesture manuals are juxtaposed with at least one leading actor from each film. The research involves films from the experimental phase (1899-1907), the transitional phase (1908-1913), and the feature film phase (1912-1922). Specifically, the films are: King John (1899), Le Duel d'Hamlet (1900), La Diable et la Statue (1901), Duel Scene from Macbeth (1905), The Taming of the Shrew (1908), The Tempest (1908), A Midsummer Night's Dream (1909), Il Mercante di Venezia (1910), Re Lear (1910), Romeo Turns Bandit (1910), Twelfth Night (1910), A Winter's Tale (1910), Desdemona (1911), Richard III (1911), The Life and Death of King Richard III (1912), Romeo e Giulietta (1912), Cymbeline (1913), Hamlet (1913), King Lear (1916), Hamlet: Drama of Vengeance (1920), and Othello (1922). The gestures used by actors in the films are compared with Gilbert Austin's Chironomia or A Treatise on Rhetorical Delivery (1806), Henry Siddons' Practical Illustrations of Rhetorical Gesture and Action; Adapted to The English Drama: From a Work on the Subject by M. -

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema a Thesis

The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Jordan G. Parrish August 2017 © 2017 Jordan G. Parrish. All Rights Reserved. 2 This thesis titled The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema by JORDAN G. PARRISH has been approved for the Film Division and the College of Fine Arts by Ofer Eliaz Assistant Professor of Film Studies Matthew R. Shaftel Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract PARRISH, JORDAN G., M.A., August 2017, Film Studies The Undead Subject of Lost Decade Japanese Horror Cinema Director of Thesis: Ofer Eliaz This thesis argues that Japanese Horror films released around the turn of the twenty- first century define a new mode of subjectivity: “undead subjectivity.” Exploring the implications of this concept, this study locates the undead subject’s origins within a Japanese recession, decimated social conditions, and a period outside of historical progression known as the “Lost Decade.” It suggests that the form and content of “J- Horror” films reveal a problematic visual structure haunting the nation in relation to the gaze of a structural father figure. In doing so, this thesis purports that these films interrogate psychoanalytic concepts such as the gaze, the big Other, and the death drive. This study posits themes, philosophies, and formal elements within J-Horror films that place the undead subject within a worldly depiction of the afterlife, the films repeatedly ending on an image of an emptied-out Japan invisible to the big Other’s gaze. -

Margaret Hepworth

Margaret Hepworth Also Known As: Mrs. Hepworth, Margaret Hope McGuffie, Margarete "McGuffie" Hepworth Lived: 1874 - October 9, 1917 Worked as: family business partner, film actress, screenwriter Worked In: United Kingdom: England by Tony Fletcher Margaret Hope McGuffie was born in 1874 at Charlton in Lancashire, England. By 1900, the family had moved to Chapel-En-Le Frith in Derbyshire, approximately twenty miles from Manchester. One of her brothers, John, who worked as a games master on the steamship The Argonaut had met the filmmaker Cecil Hepworth on board on his way to Algiers to film a solar eclipse. The two men became friends, and when they returned to Britain, Cecil was invited to meet the McGuffie family, who lived not far away from where Cecil was filming for the showman A.D. Thomas. Cecil was advised to wear evening dress for dinner, which was the practice of the McGuffie family. This may explain why in Rescued by Rover (1905), Cecil is seen wearing top-hat and tails. Cecil and Margaret were married at Buxton, Derbyshire, on February 11, 1902. Cecil later recalled in his memoirs Came the Dawn: “I had been married about a year and my wife, broken in to film work, played the part of “The White Rabbit” in Alice in Wonderland” (63). He recalled that the film Rescued by Rover (1905) was a family affair. “My wife wrote the story; my baby, eight months old, was the heroine; my Dog, the hero; my wife, the bereaved mother and myself, the harassed father” (67). The film was shot three times, the second and third version approximately five months after the first version. -

Resources and Bibliography

RESOURCES aND BIBlIOGRaPHY ARCHIVES, LIBRaRIES & MUSEUmS Barnes Collection, St Ives, Cornwall, England. Barnes Collection, Hove Museum & Art Gallery, Brighton & Hove, England. [concentrates on South Coast of England film-makers and film companies] Brighton Library, Brighton & Hove, England. British Film Institute National Film Library, London, England. [within Special Collections at the BFI is found G. A. Smith’s Cash Book and the Tom Williamson Collection] British Library Newspaper Library, London, England. Charles Urban Collection, National Science & Media Museum, Bradford, England. Hove Reference Library, Brighton & Hove, England. Library of Congress, Washington, USA. Museum of Modern Art, New York, USA. The National Archives, Kew, England. National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site, West Orange, New Jersey. Available online through the site, Thomas A. Edison Papers (Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. South Archive South East, University of Brighton, Brighton & Hove, England. University of Brighton Library, St Peter’s House, Brighton & Hove, England. FIlm CaTalOGUES Paul, Robert. 1898. Animated Photograph Films, List No. 15. London. [London: BFI Library] © The Author(s) 2019 279 F. Gray, The Brighton School and the Birth of British Film, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-17505-4 280 RESOURCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY ———. 1901. Animatograph Films—Robert Paul; Cameras, Projectors & Accessories. London. [Paris: La Cinématheque Française] We Put the World Before you by means of The Bioscope and Urban Films. 1903. London: Charles Urban Trading Company. [New York: Museum of Modern Art; Media History Digital Library] Urban Film Catalogue. 1905. London: Charles Urban Trading Company. Republished in, Stephen Herbert. 2000. A History of Early Film, Volume 1. London: Routledge. -

Proquest Dissertations

"The Cross-Heart People": Indigenous narratives,cinema, and the Western Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Hearne, Joanna Megan Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 17:56:11 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/290072 •THE CROSS-HEART PEOPLE": INDIGENOLJS NARRATIVES, CINEMA, AND THE WESTERN By Joanna Megan Heame Copyright © Joanna Megan Heame 2004 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2004 UMI Number: 3132226 Copyright 2004 by Hearne, Joanna Megan All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI UMI Microform 3132226 Copyright 2004 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O.